Frank Bowling cements his status as a modern master with Tate Britain retrospective

After six decades, the British artist is finally getting his dues as a gently dazzling survey of his paintings opens in London

Frank Bowling has been at it for a while, six decades to be precise, which might make you wonder why you haven’t heard much about him before. While his canonic contemporaries David Hockney, Pauline Boty and Patrick Caulfield were parting the waves in Britain, Bowling’s singular approach to painting was overlooked – arguably one of the most heinous artistic oversights of the last century. At long last, London’s Tate Britain is giving Bowling his due. The Guyana-born artist’s first retrospective is a nine-room whopper taking us phase by phase through an enormous body of work that, according to the show’s curator Elena Crippa, ‘holds an overwhelming feeling of vitality and openness to all the possibilities of life’.

Bowling landed on British soil as a teenager in 1953. Back then poetry was more on his agenda than art, but after some convincing by artist and friend Keith Critchlow, Bowling took up studies at the Royal College of Art. It soon became clear that the British art scene was leaning towards figurative, narrative-laden painting, whereas Bowling favoured shapes, structures and colour. This might be one reason why he was snubbed at the time.

He moved to New York in 1966 drawn by rumours of a peculiar movement called abstract expressionism stirring across the pond. He was met with garish colours, gestural improvisation and new dilemmas: as the civil rights movement intensified, artists of colour began to feel pressure to rank politics above aesthetics. This created tension between what Bowling ‘ought’ to be making work about, and what he wanted to create; to embody the sadistic horrors of black oppression, but avoid a scenario where, as an artist, his ancestry became his defining characteristic.

South America Squared, 1967, by Frank Bowling, acrylic and spray paint on canvas.

His seminal essays were a backdrop to his artistic sentiments: ‘By a rare piece of luck [perhaps it's an historical imperative] we have had a spate of black shows: individual, collective, old, new. But it is neither possible nor desirable to separate this sudden appearance of black shows from the extant political mood,’ he wrote in 1970. Throughout his career, Bowling has had one finger on the pulse of western modernity and another on his native Guyana.

Nowhere is this more starkly laid out than in Cover Girl (1966). A central figure embodies London’s swinging sixties with tightly clipped Vidal Sassoon haircut and Pierre Cardin dress. In the background, his childhood home in Guyana lurks like a hard-edged pop art print, dilapidated in the shadow of a bleak cloud. This is an intense conversation between identity, displacement, the fall of empire and the rise of modernism.

This is not the show of an artist looking to have his ego massaged. In earlier work, every other piece is homage to someone else: Caro’s carnival of banal objects, Jasper Johns’ chaotic cartography, or Turner’s hostile wash of marine turbulence. Some early figurative work like Birthday (1962) bears uncanny resemblance to Francis Bacon. Then come the map paintings, where bold hues are branded with vague outlines of southern-hemisphere landmasses, a room filled with these induces the same meditative introspection as Rothko’s Chapel.

As the work matures, Bowling’s work spurns narrative to become more touchy than feely. Abstraction gets assertive and familiarity gets swallowed up in these lumpy, foam-filled murals. Acrylic gel is palette-knifed into rippling protrusions, and paint, form and kaleidoscopic colour steal the limelight. Great Thames IV (1989) is like Monet’s Water Lilies but in a hazy, algae-ridden London waters. View it from afar and miss half the story: Bowling has embedded the surface with a bric-a-brac of objects you may well dredge from the Thames’ silt.

At 85, Bowling still paints every day from his East London studio. Well, he carefully directs from a seated position as assistants pour, drip and splash paint across his vast canvases. Is Bowling worried he’ll lose his touch through lack of contact? Absolutely not. ‘I can see more of what’s happening and use these nimble people, my new painting tools, to do more of what I want to have done,’ he says. Bowling never let himself get comfortable. A relentless experimenter, persistent intellectual, and shape-shifting creative – you greet an entirely different artist than you leave at the exit. He may have been built in the mould of abstract expressionism, but being with Bowling’s work is like unearthing an uncharted chunk of history.

Cover Girl, 1966, by Frank Bowling, acrylic, oil paint, and silkscreened ink on canvas.

Ah Susan Whoosh, 1981, by Frank Bowling, medium acrylic paint on canvas.

Ziff, 1974, by Frank Bowling, acrylic paint on canvas.

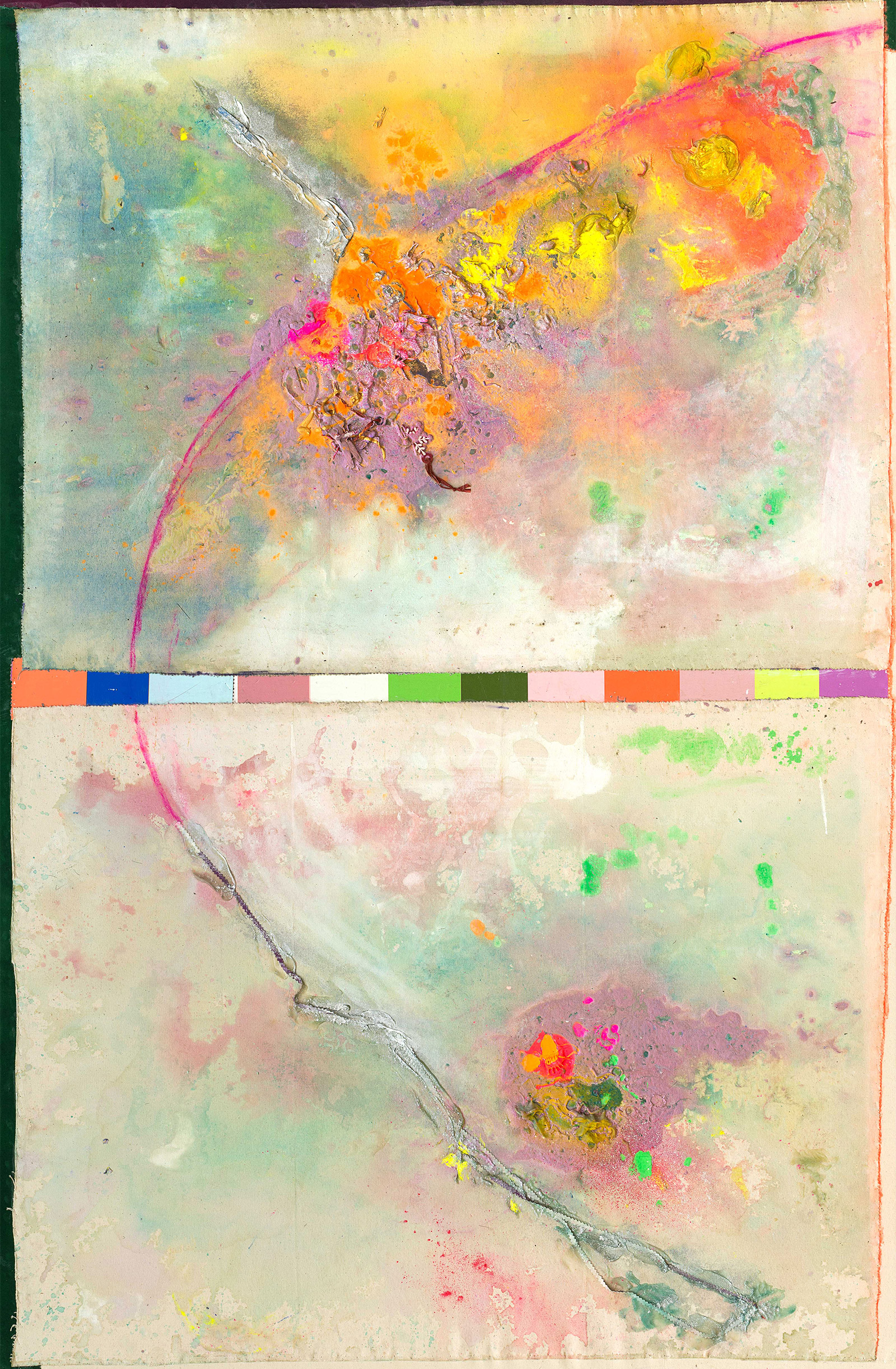

Iona Miriam’s Christmas Visit To & From Brighton, 2017, by Frank Bowling, acrylic paint and plastic objects on collaged canvas.

INFORMATION

‘Frank Bowling’ is on view until 26 August. For more information, visit the Tate Britain website

ADDRESS

Tate Britain

Millbank

London SW1 4RG

Receive our daily digest of inspiration, escapism and design stories from around the world direct to your inbox.

Harriet Lloyd-Smith was the Arts Editor of Wallpaper*, responsible for the art pages across digital and print, including profiles, exhibition reviews, and contemporary art collaborations. She started at Wallpaper* in 2017 and has written for leading contemporary art publications, auction houses and arts charities, and lectured on review writing and art journalism. When she’s not writing about art, she’s making her own.

-

The Bombardier Global 8000 flies faster and higher to make the most of your time in the air

The Bombardier Global 8000 flies faster and higher to make the most of your time in the airA wellness machine with wings: Bombardier’s new Global 8000 isn’t quite a spa in the sky, but the Canadian manufacturer reckons its flagship business jet will give your health a boost

-

A former fisherman’s cottage in Brittany is transformed by a new timber extension

A former fisherman’s cottage in Brittany is transformed by a new timber extensionParis-based architects A-platz have woven new elements into the stone fabric of this traditional Breton cottage

-

New York's members-only boom shows no sign of stopping – and it's about to get even more niche

New York's members-only boom shows no sign of stopping – and it's about to get even more nicheFrom bathing clubs to listening bars, gatekeeping is back in a big way. Here's what's driving the wave of exclusivity

-

Out of office: The Wallpaper* editors’ picks of the week

Out of office: The Wallpaper* editors’ picks of the week'Tis the season for eating and drinking, and the Wallpaper* team embraced it wholeheartedly this week. Elsewhere: the best spot in Milan for clothing repairs and outdoor swimming in December

-

Out of office: The Wallpaper* editors’ picks of the week

Out of office: The Wallpaper* editors’ picks of the weekFar from slowing down for the festive season, the Wallpaper* team is in full swing, hopping from events to openings this week. Sometimes work can feel like play – and we also had time for some festive cocktails and cinematic releases

-

The Barbican is undergoing a huge revamp. Here’s what we know

The Barbican is undergoing a huge revamp. Here’s what we knowThe Barbican Centre is set to close in June 2028 for a year as part of a huge restoration plan to future-proof the brutalist Grade II-listed site

-

Out of office: The Wallpaper* editors’ picks of the week

Out of office: The Wallpaper* editors’ picks of the weekIt’s wet, windy and wintry and, this week, the Wallpaper* team craved moments of escape. We found it in memories of the Mediterranean, flavours of Mexico, and immersions in the worlds of music and art

-

Each mundane object tells a story at Pace’s tribute to the everyday

Each mundane object tells a story at Pace’s tribute to the everydayIn a group exhibition, ‘Monument to the Unimportant’, artists give the seemingly insignificant – from discarded clothes to weeds in cracks – a longer look

-

Out of office: The Wallpaper* editors’ picks of the week

Out of office: The Wallpaper* editors’ picks of the weekThis week, the Wallpaper* team had its finger on the pulse of architecture, interiors and fashion – while also scooping the latest on the Radiohead reunion and London’s buzziest pizza

-

Out of office: The Wallpaper* editors’ picks of the week

Out of office: The Wallpaper* editors’ picks of the weekIt’s been a week of escapism: daydreams of Ghana sparked by lively local projects, glimpses of Tokyo on nostalgic film rolls, and a charming foray into the heart of Christmas as the festive season kicks off in earnest

-

This Gustav Klimt painting just became the second most expensive artwork ever sold – it has an incredible backstory

This Gustav Klimt painting just became the second most expensive artwork ever sold – it has an incredible backstorySold by Sotheby’s for a staggering $236.4 million, ‘Portrait of Elisabeth Lederer’ survived Nazi looting and became the key to its subject’s survival