From David Hockney to modern horror: the enduring symbolism of the swimming pool

On the sixtieth anniversary of David Hockney introducing the swimming pool into his painting California Art Collector (1964), we look at the enduring role of the swimming pool in art and culture

Sixty years since David Hockney first plunged himself into the quiet magic of the swimming pool, purpose-built baths still continue to enchant

Perhaps there was something in the water. But it didn’t take David Hockney long to paint a swimming pool after he crossed the pond to Los Angeles in 1964. Within a few months of moving to the city that, as Frank Lloyd once quipped, is what you would get if you tipped the world upside down and dislodged everything loose, the pop painter found a subject he would cling to for decades.

A swimming pool first trickled into the corner of Hockney’s painting California Art Collector (1964); one featured more prominently in Picture of a Hollywood Pool of the same year. Both acrylics, they coated Hockney’s honed style with his newfound sense of Cali Cool. Although he was only dipping a toe into the water, early signs of what was to come – a perfect stone border surrounding the pool, squiggly dark blue waves – lay within.

And so began his deep dive into the subject, one which saw Hockney produce scores of paintings and collages centred on the swimming pool, including The Splash series completed in 1967 and a collection of lithographs. The beauty of Hockney’s swimming pools is that they never appear hackneyed, always new to the eye. So much so that his work is still being shown and with some verve; David Hockney: Drawing From Life is currently on at the National Portrait Gallery and Bigger & Closer has just finished at London’s Lightroom.

The latter is an immersive, interactive look at Hockney’s work, inviting visitors to experience projections of the paintings in the venue’s capacious space. Swimming pools, of course, abound; an entire “chapter” of the narrative is dedicated to them. “We were able to play with scale to make visitors feel like they’re really in these paintings - projecting onto all four walls and the floor. Nico Muhly wrote a beautiful score for the chapter which is as close to the feeling of being in a pool as I think it’s possible to get in musical form,” says 59 Productions co-founder Mark Grimmer.

But Hockney is far from a lone figure when it comes to this aquatic topic. Indicative of this is another UK exhibition, Bathers, which was on display at Saatchi Yates in the summer. The show collated dozens of paintings depicting subjects caught in the act of swimming, skinny dipping and diving. Alongside two Hockneys, it included the Floating Figure II by Neil Stokoe, who studied at the RCA at the same time as Hockney. “Influence is a tricky thing as it's not linear. It's a swirling, cybernetic vortex,” says Neil’s son Jack, noting that the inspiration between Hockney and Stokoe’s style may have worked both ways.

The exhibit’s sprawling timeline, spanning from 1662 to 2023, is a reminder, of course, that Hockney did not invent the pool picture. The Bradford-born painter did, though, start a ripple effect, reframing the swimming pool, which first sprung up in Britain around the mid-nineteenth century, as something alluringly sensual and tacitly tactile. This is highlighted by the vast amount of new work that featured in Bathers: thirteen of the pieces were painted this year.

Many such artists have assumed the swimming pool as their main muse, all working to distil its true essence. Eric Fischl’s suburban imagery, which also featured in Bathers, frequently contains poolside families and lovers, capturing the domestication of swimming. Chan Wai Lap obsessively documents pools that remind him of his childhood, including a huge sculpture outside Hong Kong Museum of Art installed earlier this year. Kate Williams, too, is currently creating a buzz for her quilts depicting gorgeous, geometric pools.

Artist and writer Leanne Shapton meanwhile brings a multidisciplinary approach. Her illustrated book Swimming Studies followed her journey from competitive swimming to composing swimming pool pictures, writing with a balletic fluidity. “I wanted an accounting of every pool I’d swum in. I work in series, where the quantity and repetition wind up being parts of a whole,” she explains. Each illustration is represented in grid format. “It equalises each pool— so the 1992 Olympic Trials 50m venue is given the same treatment as the overchlorinated Holiday Inn Express pool in Minnesota,” she explains.

Shapton also wrote the foreword for Lou Goddard’s 2020 book Pools. “I was given a lot of freedom for that introduction. Lou asked me out of the blue and I liked the look of the book, I found it very evocative and seductive,” Shapton says. Her introduction paints the pool as a blank canvas, pointing to its ability to take on new meanings. “A pool. Look at it. It's a smooth, contained and containing body of water, a blank canvas, a fresh sheet of paper, a zero-gravity ride of a sort,” she writes.

But what else makes the swimming pool such a bottomless well of inspiration for artists? And what does it symbolise beneath the surface?

For Hockney, it was all about the lifestyle. The swimming pool, a rare luxury in the UK, was more in reach in LA, an object of affordable affluence and accessible aspiration. “David points out [for the voiceover of the exhibit] that we think of swimming pools in the UK as symbols of luxury, whereas they’re much more commonplace in California, and that’s reflected in how they appear in our cultures too,” Grimmer says.

Regardless, swimming pools are still expensive to design, build and maintain, a sign of financial comfort and leisure time that spans from suburban gardens all the way up to the vertiginous roofs of opulent hotels. Lazily lying on a lilo in a private pool is a sexy, not quiet, luxury. “Hockney captured the care-free, light-filled land of possibility that Los Angeles represented to a young man from Bradford in the 1960s,” Grimmer adds. “As a symbol of warmth, brightness, fun, sexiness, it’s hard to beat an outdoor pool in California.”

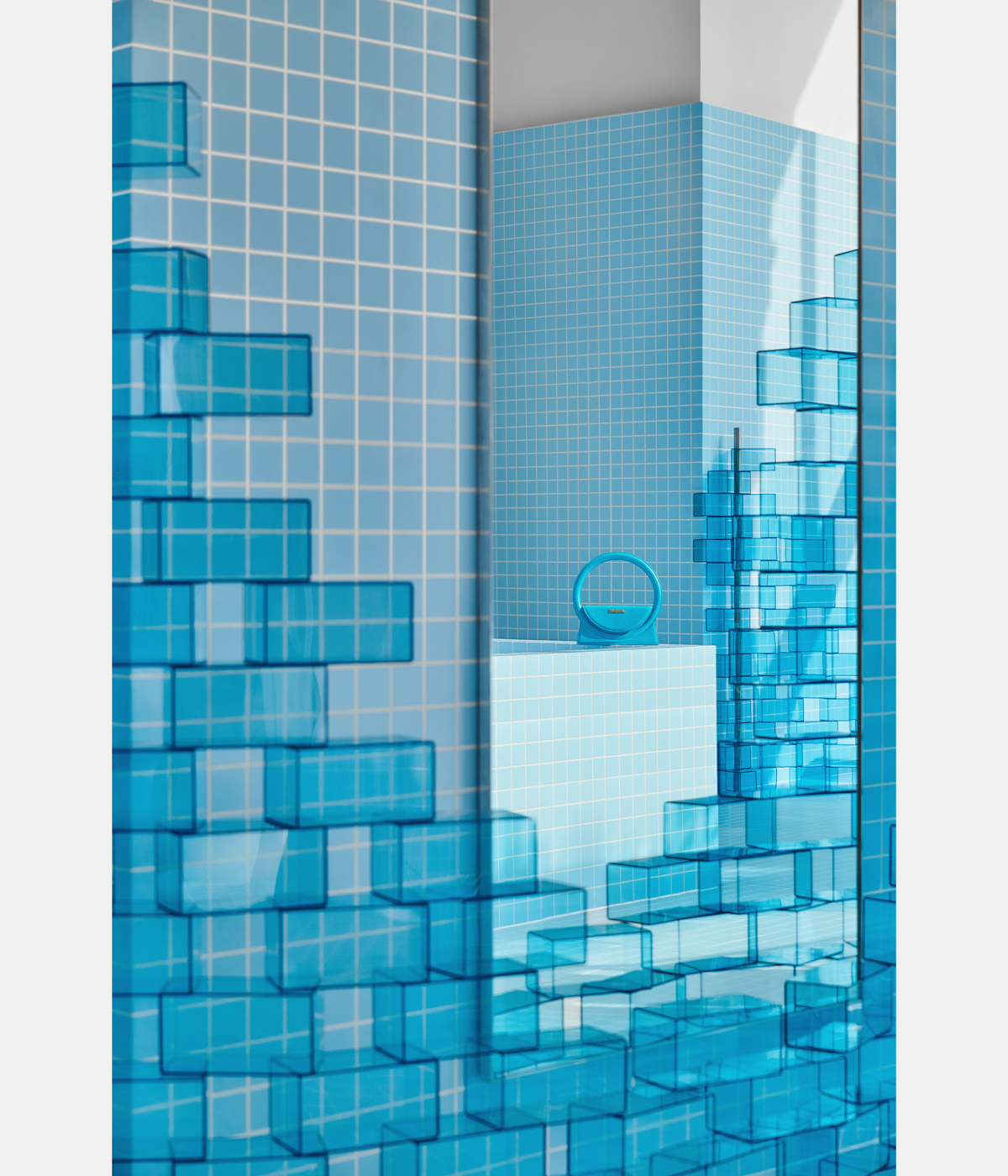

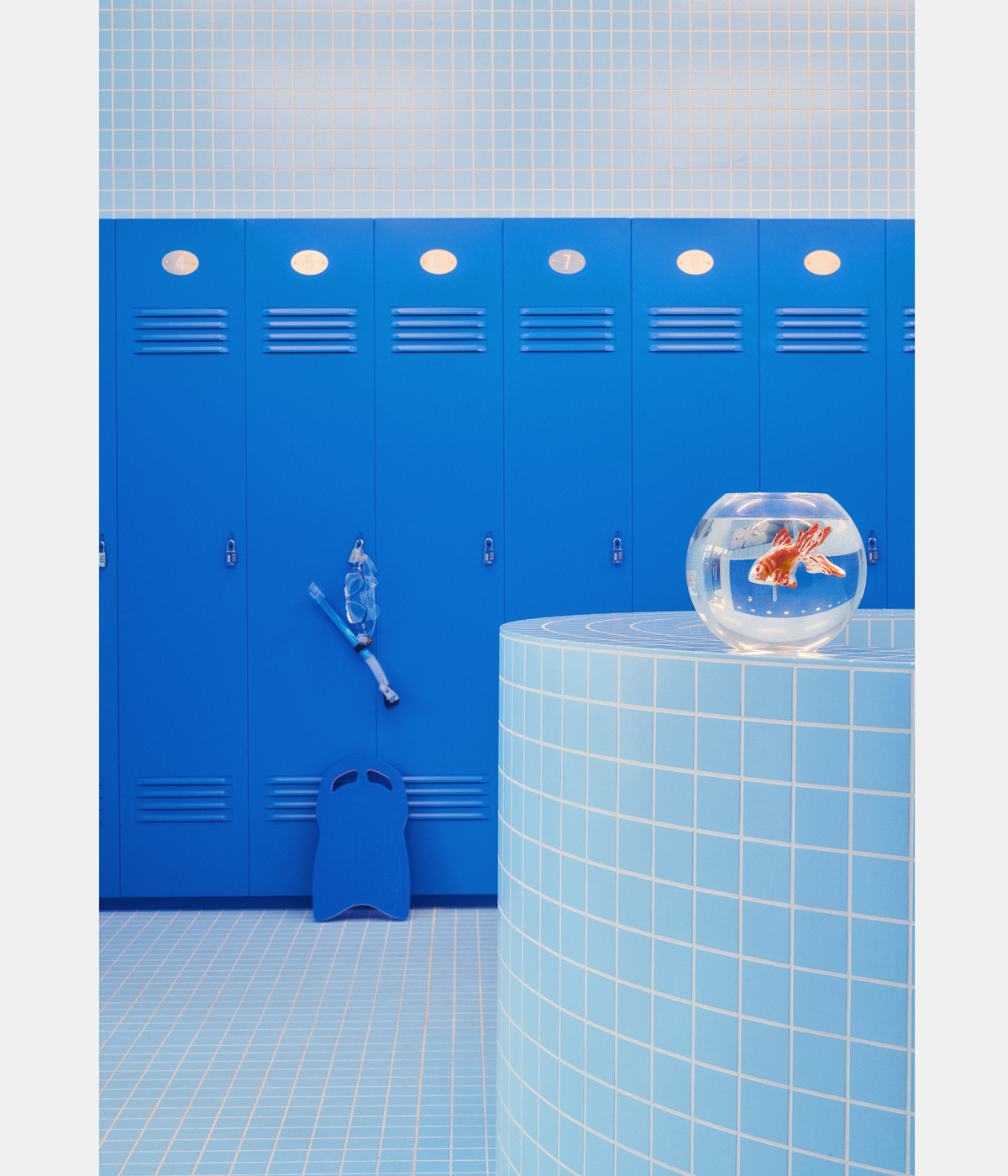

Perhaps this sense of luxury is why high fashion, too, has used the swimming pool as a springboard. Simon Porte Jacquemus has frequently included the swimming pool in his campaigns and last year created a surreal interactive activation in Selfridges, Le Bleu, complete with actors enacting scenes in changing rooms, dazzling tiles and pristine blue lockers. “One of Jacquemus’ first shows was in a swimming pool. We wanted to explore their world,” says Seb Price, a lead creative from Random Studio, which worked on the project. For Price, the value is in the sense of voyeurism. “The cabins served as a great way to contain surprises and narrative elements, allowing visitors to discover and play, to hide and reveal…the changing room is a place of privacy, but it is also very public,” he says.

While Le Bleu was a temporary build, swimming pools are of course in themselves a form of architecture and sculpture. From grand Victorian public baths through to cutting-edge, state-of-the-art infinity pools, they are as much a water feature as a space for athleticism (though, as Grimmer dryly notes: “I can tell you from personal experience that Leyton Leisure Centre at 9am on a Saturday is about as far from architectural art as it’s possible to get.”)

It’s why some swimming pools have become multi-purpose venues, from the stunning La Piscine Museum in Lille to Goldsmiths' converted art studios to Victoria Baths in Manchester, taken over by Chanel in December 2023. They can even display other forms of art; just last month, John Lennon's psychedelic swimming pool mosaic went on auction, expecting to fetch six figures.

This swimming pool also offers the chance for artists to experiment with form. “I suspect that Neil's interests were formal. Something about the figure, the water, the immersion and less of the lifestyle," Jack Stokoe says. “It presents a particularly enticing challenge for an artist because you're using a fluid medium to depict a fluid media but creating a still image,” he adds. This also applies to Neil’s friend, Hockney. “There is a difficulty to painting water, whether it’s a swimming pool, a pond, a puddle, a river, a shower or a lawn sprinkler (he’s painted all of them),” Grimmer says. “Painting water is a technical challenge that Hockney relished - and still does.”

But for those of us who enjoy, rather than create, art from afar the real enigmatic magnetism at the centre of the swimming pool is memory. Both private and public pools take us back to the amplified warbles of school swimming lessons, the blissful escape from heat on heady summer holidays and swirling thoughts worked through during long, solo swims. Price used a chlorine-inspired scent in La Bleu to stimulate this. “It brought people closer to the feeling of this nostalgia, to the sensation of being present in a changing room,” he says. Shapton, meanwhile, believes it reinstates our earliest state of being. “It’s a womb. Life-giving, mysterious,” she says.

Some of these memories are tarnished by a sense of darkness. Cinema has long depicted this; for every luxurious scene there are two tarred by the same brooding brush, representing something malevolent lurking in the water, from The Swimming Pool (1969) to upcoming horror film Night Swim, featuring a haunted pool. “Movies are awash with people who shouldn’t be in pools ending up in pools with other people who also shouldn’t be in pools,” Grimmer says. “There is a fear of going in the deep end. A contained body of water can still be somewhere you can die,” Jack Stokoe agrees, pointing to the cruciform figurine in Man in Floating Figure II.

But while the swimming pool still represents this decadence and sense of potential danger, swimming has become more about wellbeing than being well off. This is especially true following the pandemic, which saw interest in outdoor swimming and lidos spiral. “Perhaps it is their minimalist aesthetic, their lack of modernity and technology, or perhaps the effect of social media, that otherwise ordinary spaces are now the protagonists of our media,” Price thinks.

Grimmer agrees. “It seems to be much more about carving out quiet time and uncluttering one’s mind than about luxury or hedonism,” he says. “If the backyard pool in the Hollywood Hills represented 1960s Los Angeles, I think a brisk swim in a cold outdoor Lido in London feels more apposite to the here and now.”

Wallpaper* Newsletter

Receive our daily digest of inspiration, escapism and design stories from around the world direct to your inbox.

Kyle MacNeill is a freelance arts writer who contributes to publications including The Guardian, Financial Times and New York Times. He is interested in the study of objects, niche communities and fakeness.

-

Put these emerging artists on your radar

Put these emerging artists on your radarThis crop of six new talents is poised to shake up the art world. Get to know them now

By Tianna Williams

-

Dining at Pyrá feels like a Mediterranean kiss on both cheeks

Dining at Pyrá feels like a Mediterranean kiss on both cheeksDesigned by House of Dré, this Lonsdale Road addition dishes up an enticing fusion of Greek and Spanish cooking

By Sofia de la Cruz

-

Creased, crumpled: S/S 2025 menswear is about clothes that have ‘lived a life’

Creased, crumpled: S/S 2025 menswear is about clothes that have ‘lived a life’The S/S 2025 menswear collections see designers embrace the creased and the crumpled, conjuring a mood of laidback languor that ran through the season – captured here by photographer Steve Harnacke and stylist Nicola Neri for Wallpaper*

By Jack Moss