Germaine Richier’s sculptures get their first US showing in nearly sixty years

In a 1956 photo, Germaine Richier stands over a table in the back corner of her Paris studio sorting through papers. The profile view reveals a lower lip pushed out and up in the act of discernment and a utilitarian grey ensemble that makes her nearly invisible against the ashy studio walls. She is simultaneously surrounded, protected, dwarfed, and upstaged by her sculptures: bronze figures of various sizes and patinas that are at once organic and demonic, familiar yet unknowable. A survey presented jointly by Dominique Lévy and Galerie Perrotin brings together 46 of these bewitching forms in the first US exhibition of Richier's work since 1957.

'To me, she really was the mother of post-war sculpture in Europe,' says gallerist Dominique Lévy, who assembled works from the artist's estate as well as loans from private collections. 'She aroused curiosity from the beginning and created a lot of debate about the constant dilemma of postwar art: figuration or abstraction?'

Richier (1902-1959) managed to split the difference. Classically trained, first at the École Supérieure des Beaux-Arts de Montpellier and later as a student of sculptor and Rodin protégé Antoine Bourdelle, she initially focused on busts before working her way down. After World War II, which was spent on prolonged vacation in Zurich, she began incorporating animal and vegetal elements - insects, trees, bats and toads - into bodies ravaged of all but their strange and profound humanity.

The frequent choice of dark patinated bronze intensifies the rough surfaces of the sculptures. Anna Swinbourne, who contributed an essay to the exhibition catalogue, traces this aspect of Richier's work to a formative 1935 trip to Pompeii. 'She talked very often to people that she knew about the impact that that trip had on her, to see the charred remains of human beings,' says Swinbourne, 'and I think that it's an underestimated influence in her work.'

Works from the 1950s such as 'Le Griffu' and 'Le Mandoline (ou La Cigale)' show Richier experimenting further with structure and surface. The addition of metal wire adds a lean, geometric counterpoint to her earthy figures, while polished natural bronze injects exuberance into a perforated carapace. And although Richier made a career out of defying categorisation, there are works that cross paths with the elongated lopers of Giacometti and a monumental bronze shell that would look at home in the electro-plated undersea garden of Claude Lalanne.

The masterstroke of the exhibition is the decision to eschew the sparsely populated rooms typical of contemporary shows for a more dense arrangement, heightened by a selection of Brassaï photos. 'The sculptures echo each other. They bounce off each other. So even sometimes you're disturbed, because they're too close,' says Lévy. 'When you look at the photographs of Germaine Richier in the studio, she was always working in relation to her own work. And so we tried to recreate that atmosphere.'

Her studio's atmosphere was purposely recreated for the survey, held jointly by Dominique Lévy and Galerie Perrotin at their adjoining gallery spaces in New York

Works from the 1950s such as 'Le Griffu' (right in foreground) show Richier's experimentation with structure and surface. The addition of metal wire adds a lean, geometric counterpoint to her earthy figures

From left: 'La Mante, Moyenne', 1946; 'Le Mandoline (ou La Cigale)', 1954-55; and 'L'araignée I', 1946. The frequent choice of dark patinated bronze intensifies the rough surfaces of the sculptures, creating an exuberant contrast to her work in polished natural bronze

© Germaine Richier/2014 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York/ADAGP, Paris.

'La Tauromachie', 1953. Richier's national identity is often quietly present in her sculptures. The trident is the symbol of horsemen guarding the wild horses and bulls of the Camargue, situated in the Rhône delta in the south of France.

© Germaine Richier/2014 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York/ADAGP, Paris.

Detail of 'La Forêt', 1946. This work illustrates the sculptor’s relationsip with nature and her Provençal identity. Richier wrote a letter to her mother asking her family to collect tree branches for her, which she then used in the making of this sculpture.

The masterstroke of the exhibition is the decision to eschew the sparsely populated rooms typical of contemporary shows for a more dense arrangement, heightened by a selection of Brassaï photos. 'The sculptures echo each other. They bounce off each other. So even sometimes you're disturbed, because they're too close,' says gallerist Dominique Lévy

Richier produced many sculptures on the theme of the seated woman. 'L'Eau' (right), 1953-54, was her last foray into the exploration of this motif

© Germaine Richier/2014 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York/ADAGP, Paris.

'Le Sauterelle, grande', 1955-56. Part woman, part insect, this work is a study of animal dynamism. Richier's crouched creature, defined by its sharp angles, seems ready to pounce at any minute

Detail of 'Le Sauterelle, grande' showing the figure's huge human paw with a heart discreetly etched into it © Germaine Richier/2014 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York/ADAGP, Paris

'Le Sablier III', 1953 © Germaine Richier/2014 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York/ADAGP, Paris.

ADDRESS

Dominque Lévy/Galerie Perrotin

909 Madison Avenue

New York NY 10021

Wallpaper* Newsletter

Receive our daily digest of inspiration, escapism and design stories from around the world direct to your inbox.

Stephanie Murg is a writer and editor based in New York who has contributed to Wallpaper* since 2011. She is the co-author of Pradasphere (Abrams Books), and her writing about art, architecture, and other forms of material culture has also appeared in publications such as Flash Art, ARTnews, Vogue Italia, Smithsonian, Metropolis, and The Architect’s Newspaper. A graduate of Harvard, Stephanie has lectured on the history of art and design at institutions including New York’s School of Visual Arts and the Institute of Contemporary Art in Boston.

-

Kapwani Kiwanga transforms Kvadrat’s Milan showroom with a prismatic textile made from ocean waste

Kapwani Kiwanga transforms Kvadrat’s Milan showroom with a prismatic textile made from ocean wasteThe Canada-born artist draws on iridescence in nature to create a dual-toned textile made from ocean-bound plastic

By Ali Morris

-

This new Vondom outdoor furniture is a breath of fresh air

This new Vondom outdoor furniture is a breath of fresh airDesigned by architect Jean-Marie Massaud, the ‘Pasadena’ collection takes elegance and comfort outdoors

By Simon Mills

-

Eight designers to know from Rossana Orlandi Gallery’s Milan Design Week 2025 exhibition

Eight designers to know from Rossana Orlandi Gallery’s Milan Design Week 2025 exhibitionWallpaper’s highlights from the mega-exhibition at Rossana Orlandi Gallery include some of the most compelling names in design today

By Anna Solomon

-

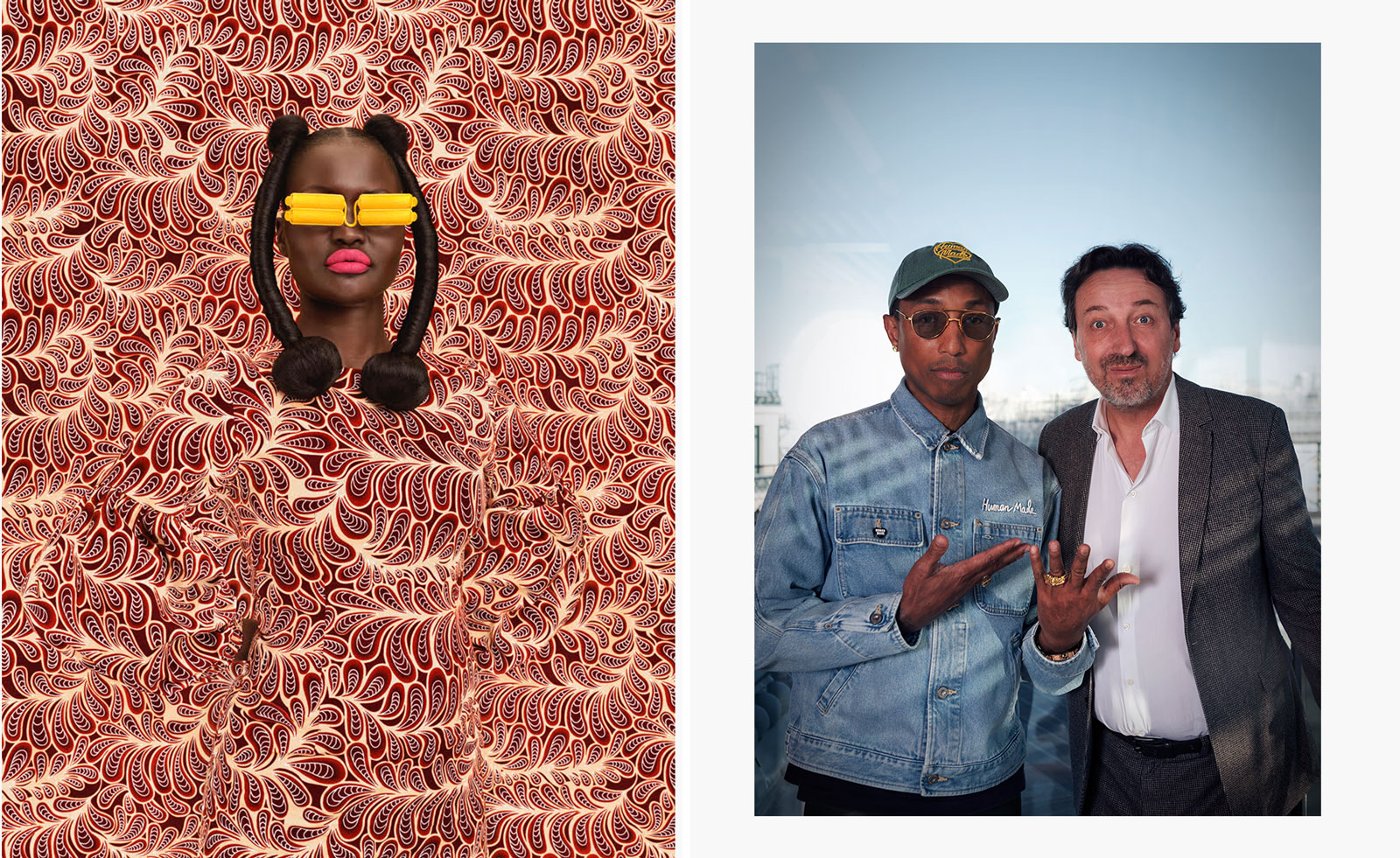

‘The Black woman endures a gravity unlike any other’: Pharrell Williams explores diverse interpretations of femininity in Paris

‘The Black woman endures a gravity unlike any other’: Pharrell Williams explores diverse interpretations of femininity in ParisPharrell Williams returns to Perrotin gallery in Paris with a new group show which serves as an homage to Black women

By Amy Serafin

-

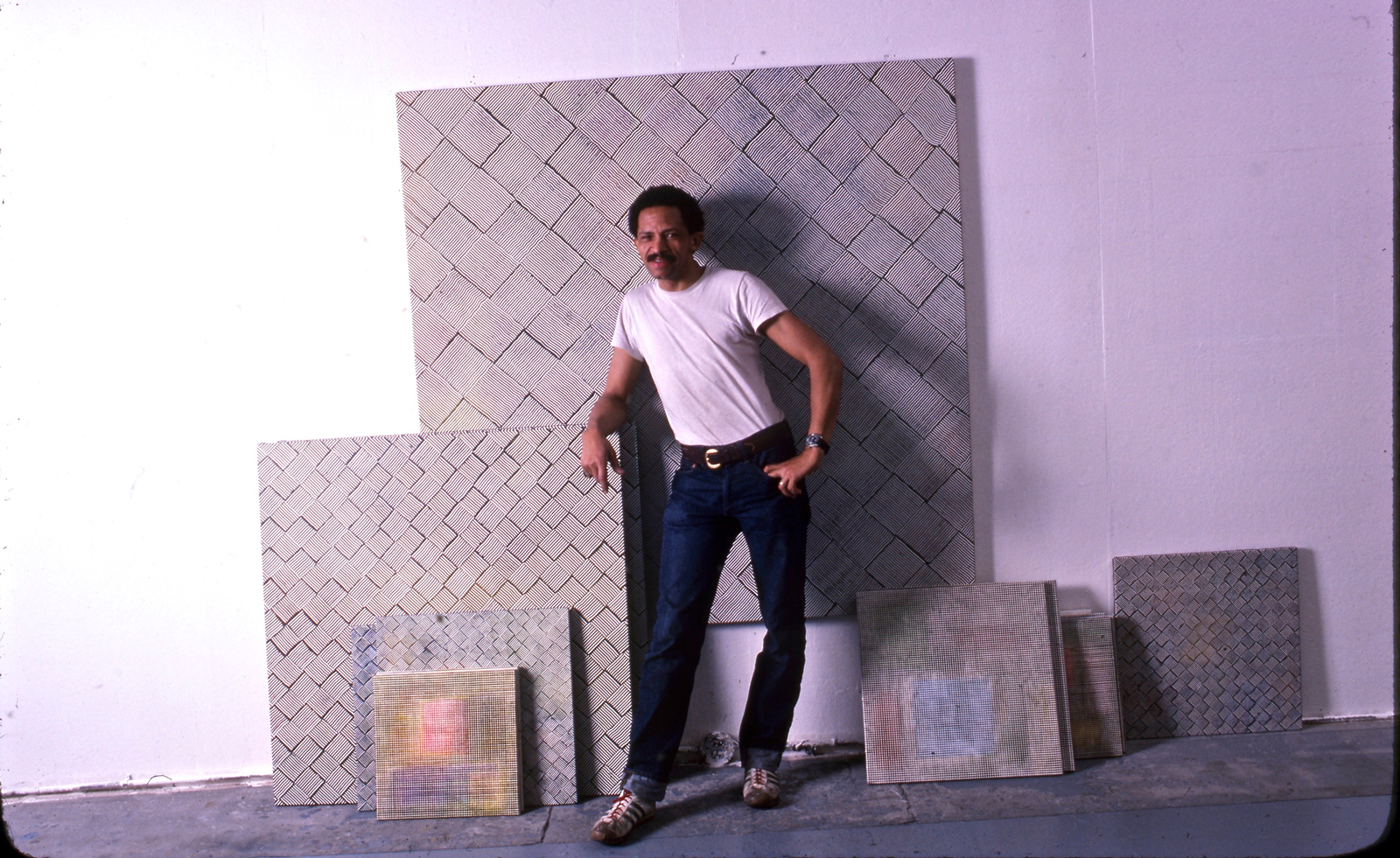

Inside Jack Whitten’s contribution to American contemporary art

Inside Jack Whitten’s contribution to American contemporary artAs Jack Whitten exhibition ‘Speedchaser’ opens at Hauser & Wirth, London, and before a major retrospective at MoMA opens next year, we explore the American artist's impact

By Finn Blythe

-

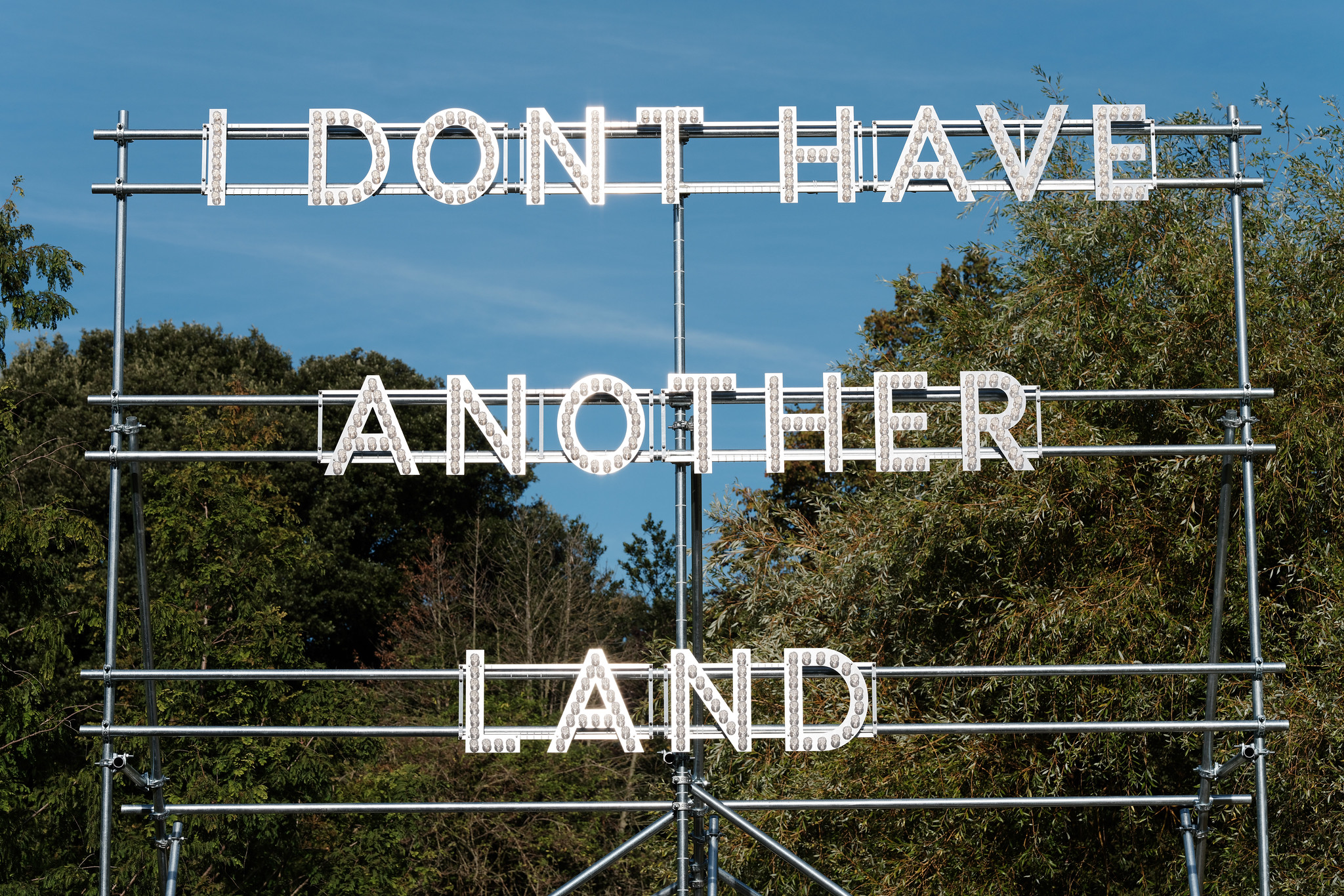

Frieze Sculpture takes over Regent’s Park

Frieze Sculpture takes over Regent’s ParkTwenty-two international artists turn the English gardens into a dream-like landscape and remind us of our inextricable connection to the natural world

By Smilian Cibic

-

Harlem-born artist Tschabalala Self’s colourful ode to the landscape of her childhood

Harlem-born artist Tschabalala Self’s colourful ode to the landscape of her childhoodTschabalala Self’s new show at Finland's Espoo Museum of Modern Art evokes memories of her upbringing, in vibrant multi-dimensional vignettes

By Millen Brown-Ewens

-

Wanås Konst sculpture park merges art and nature in Sweden

Wanås Konst sculpture park merges art and nature in SwedenWanås Konst’s latest exhibition, 'The Ocean in the Forest', unites land and sea with watery-inspired art in the park’s woodland setting

By Alice Godwin

-

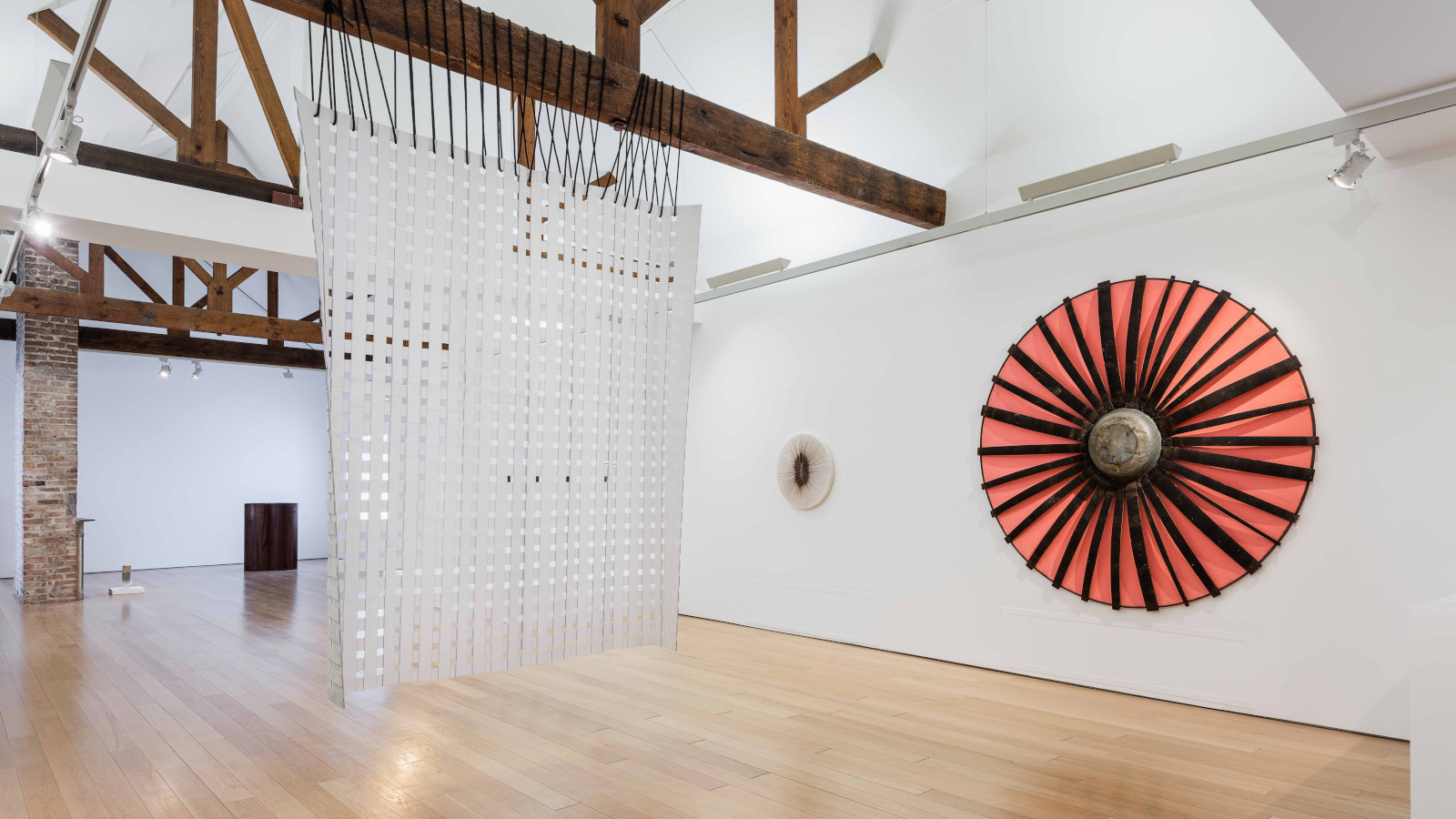

Pino Pascali’s brief and brilliant life celebrated at Fondazione Prada

Pino Pascali’s brief and brilliant life celebrated at Fondazione PradaMilan’s Fondazione Prada honours Italian artist Pino Pascali, dedicating four of its expansive main show spaces to an exhibition of his work

By Kasia Maciejowska

-

John Cage’s ‘now moments’ inspire Lismore Castle Arts’ group show

John Cage’s ‘now moments’ inspire Lismore Castle Arts’ group showLismore Castle Arts’ ‘Each now, is the time, the space’ takes its title from John Cage, and sees four artists embrace the moment through sculpture and found objects

By Amah-Rose Abrams

-

Gerhard Richter unveils new sculpture at Serpentine South

Gerhard Richter unveils new sculpture at Serpentine SouthGerhard Richter revisits themes of pattern and repetition in ‘Strip-Tower’ at London’s Serpentine South

By Hannah Silver