Helen Pashgian on pushing the limits of perception: ‘making art is like a divine itch’

Art icon Helen Pashgian’s optically majestic sculptures are a lesson in perception, as featured in the April 2022 issue of Wallpaper*. Pashgian’s solo exhibition ‘Presences’ at Site Santa Fe runs until 27 March 2022

William Jess Laird - Photography

No GPS can direct you to the Pasadena studio of Helen Pashgian. ‘You won’t find it,’ insists the artist, renowned for the technologically advanced sculptures she produced in the 1960s. On the phone (she doesn’t use a computer or email), she provides detailed instructions involving left turns and a once famed club called The Ice House.

Pashgian opens the faded blue door and ushers me into a generous workspace that she has used since the mid-1970s, with high ceilings and blocked windows to control the lighting on her translucent sculptures. Focused and fresh, with the athletic frame of an ocean swimmer, Pashgian doesn’t look or act 87. She leads the way into a room where polished spheres of marigold and emerald epoxy rest atop clear pedestals so that their colours pour downwards to rest in a band at each base. A small square at the centre of each globe appears to tunnel into a single point of light. With close attention, that point appears infinite. Each is perfect.

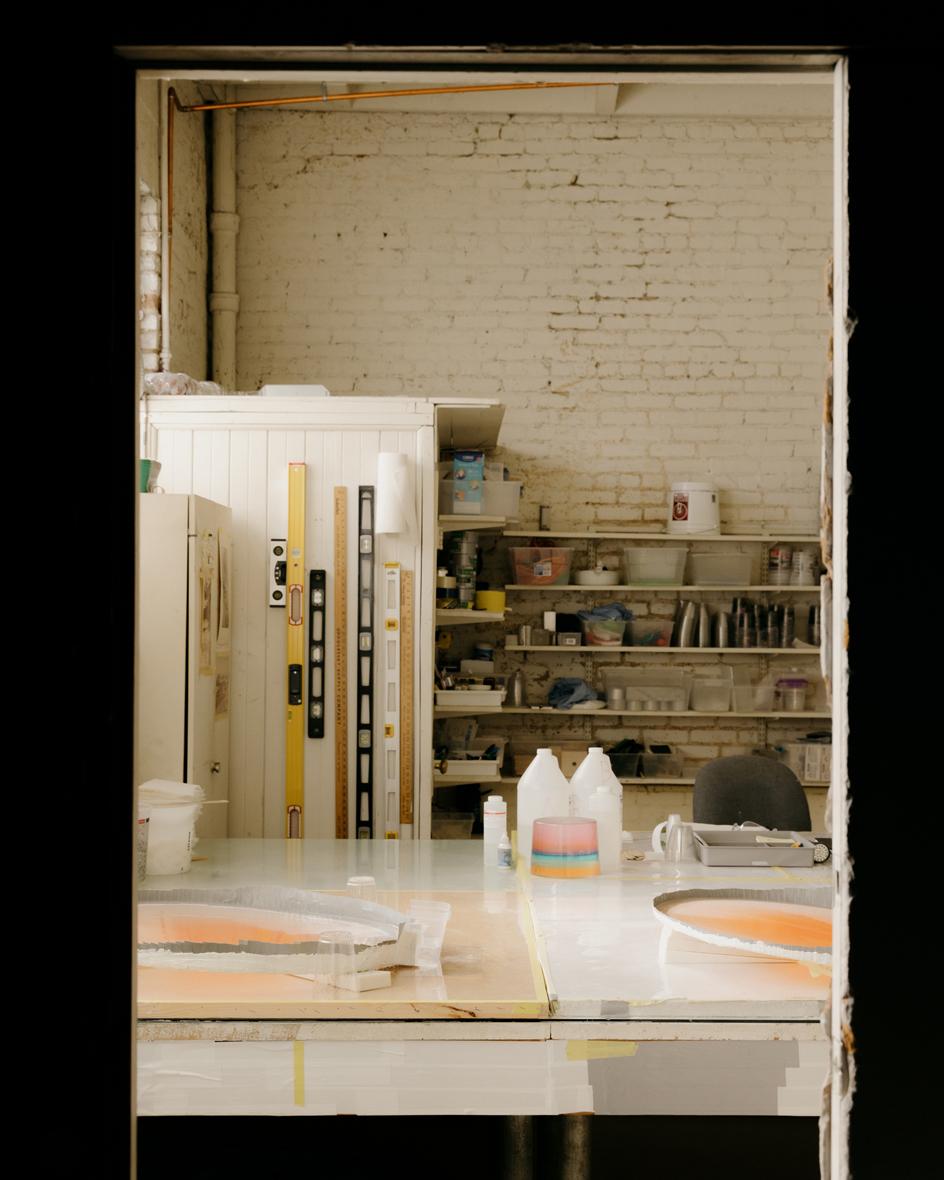

Artist Helen Pashgian in her studio, a converted piano warehouse in Pasadena, California, photographed for the April 2022 issue of Wallpaper*, on sale 10 March

Perfection, as time-consuming and frustrating as it can be for the artist, is essential. Any irregularity mars the purity of experience, which is Pashgian’s ultimate aim. When her work was first shown in the late 1960s, alongside other, similarly inclined LA artists, a critic dismissed it as ‘finish fetish’. Pashgian shrugs and says, ‘The subtlety of these pieces necessitated their being beautifully crafted and beautifully finished. But it would have been better to be known as light artists.’

Pashgian was among the first artists to grasp that post-war innovations in plastics enabled an art that could challenge perception in unprecedented ways. Yet her work is not as well known as that of her male counterparts. One of the exhibitions she was preparing for when I met her was for Lehmann Maupin – her first solo show in New York in nearly 50 years. Dealer David Maupin, a California native, understood her history and recognised her relevance. ‘It’s mind-boggling. Someone of her talent being one of the only women in the Light and Space movement and not being shown in New York.’ Titled ‘Spheres and Lenses’, the show highlighted her series of glowing globes and large mounted discs.

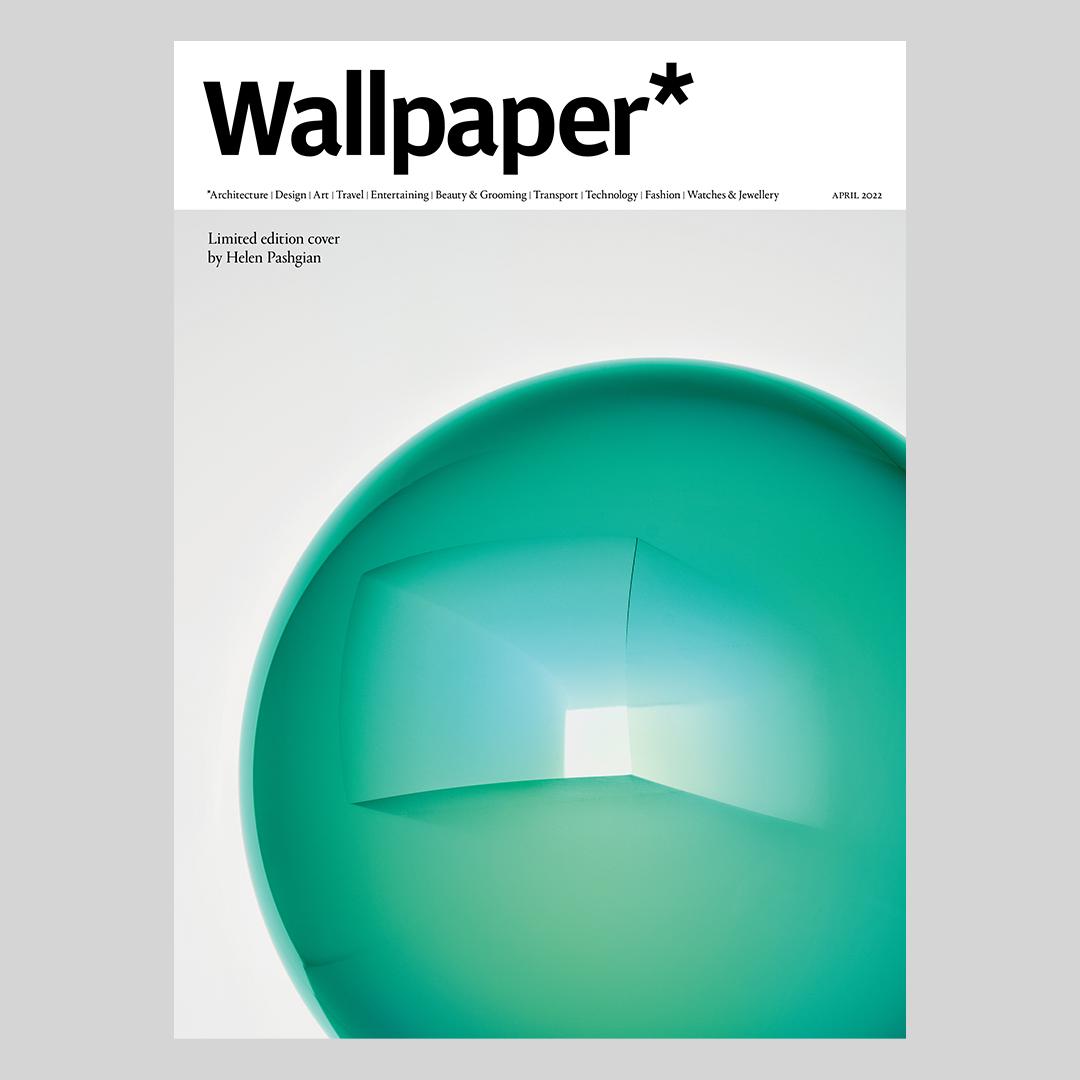

This month’s limited-edition cover features an untitled 2020 work from Helen Pashgian’s ‘Spheres’ series, which appeared in her solo show at Lehmann Maupin New York

The second exhibition she had been preparing for would take over 15,000 sq ft of Site Santa Fe in New Mexico. Organised by founding director Louis Grachos, ‘Presences’ is anchored by Light Invisible, 2014, a dozen 8ft-tall double elliptical columns of acrylic that radiate soft light in a darkened gallery and which have been loaned by the Los Angeles County Museum of Art (LACMA). Grachos was impressed by the artist’s unprecedented leap in scale from tangible if transparent objects to expansive installations. ‘The amazing thing was seeing an artist continually innovating and pushing the boundaries of her work and her material.’

This apotheosis of recognition is overdue for Pashgian. Sophisticated and worldly, she lives near her studio in Pasadena and not that far from her childhood home. She has never married nor had children, and one senses her interior determination to prioritise life as an artist. ‘Making art is like a divine itch. At first, I was very insecure and self-critical. I’ve become more confident.’

Forcefully, she dismisses people who say such recognition should have happened sooner. ‘People have actually said to me, and rudely, “Don’t you wish you could have done this when you were 35?” This is the truth: I couldn’t have done it when I was 35. I didn’t know enough. I hadn’t experienced enough. Every artist has their own personal evolution. I’m a very slow bloomer. These pieces are a culmination of that first lens, made 50 years ago. They’ve become more sophisticated and I’ve gotten better at doing them because they’re technically very difficult.’

Wallpaper* Newsletter

Receive our daily digest of inspiration, escapism and design stories from around the world direct to your inbox.

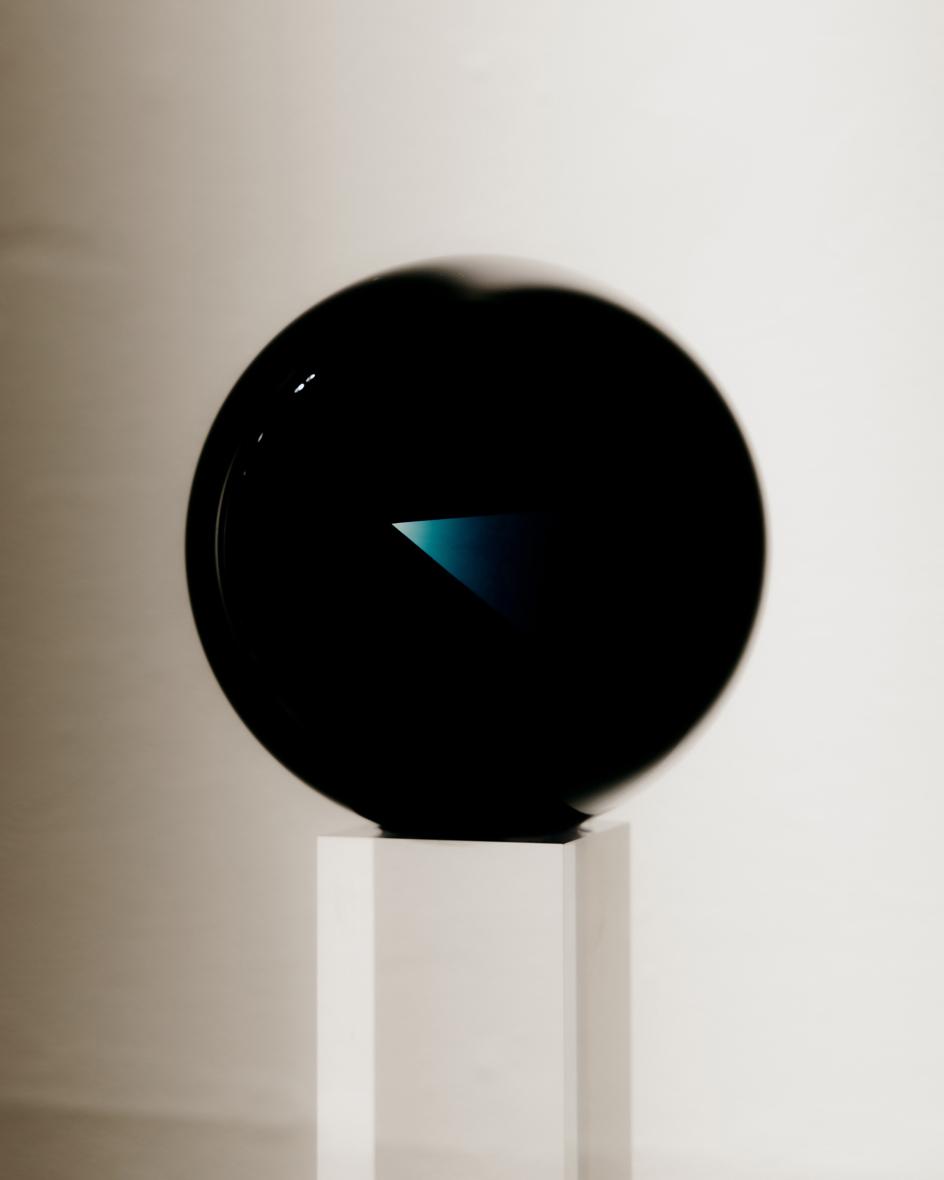

Top: Untitled, 2021, cast epoxy with formed acrylic elements, sphere diameter 6 inches. Above: Untitled, 2021, cast urethane with artist-made acrylic pedestal, lens diameter 45 inches

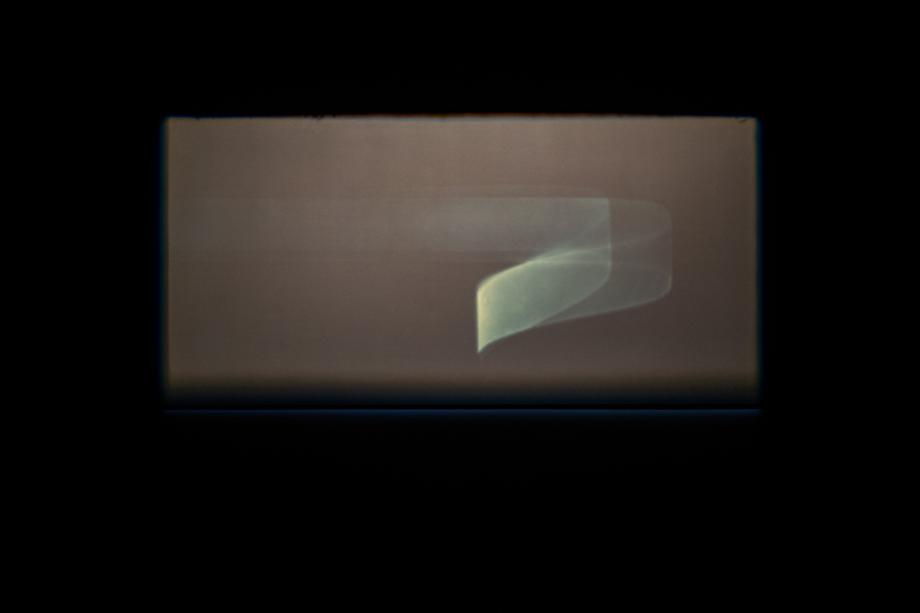

That is an understatement in describing the production of her newest pieces, which she categorises as ‘Lenses’. Banning the use of a camera or notebook, she offered me a chair in a darkened portion of the studio. Her controlled lighting gradually revealed a hint of spherical hue like the edge of a sunrise and, as it intensified, the piece disappeared into a cloud of pale colour. It was difficult to discern that the sculpture itself was a 5ft disc of multicoloured urethane that appeared to float above its acrylic base. ‘What happens, and this is really important, is that as the light recedes, the outer colour begins to fade and you’re left with the centre colour, which gets brighter; then it too begins to contract and disappear,’ says Pashgian. ‘People say it pulls them into their own thoughts.’

This was Pashgian’s first attempt to make a 5ft lens since 1971, when she showed a disc-shaped polyester resin sculpture at the California Institute of Technology (Caltech). It had launched a programme to encourage scientists to work with artists like Pashgian, who were using complex combinations of plastics. She had managed to cast the large piece, but was frustrated with the finishing. Fellow artist Peter Alexander was in the same programme and recommended Jack Brogan, a fabricator who had been discovered by Robert Irwin. Brogan picked up the piece with the help of five men, completed the polishing and returned it in time for an opening at the Caltech gallery. That sculpture was such a success, it was promptly stolen. To this day, there is only a photograph of Pashgian with a big transparent grey disc weighing 200lb.

Above: Untitled, 2021, cast epoxy with resin, sphere diameter 6 inches

She can laugh at that story today, but the creation of her new 5ft lens provided closure, as well as opening her path to future endeavours. Today, Pashgian still executes every detail of her sculptures in her studio, with trial-and-error use of colour, although specific finishing details sometimes require outside processes. ‘I think artists have a vision of something; they have no clue how to do it, but they find a way,’ she explains. From the beginning, she has also kept detailed records of all her completed works.

Difficult to reproduce (colour photography was rare) and often misunderstood, the Light and Space movement has waxed and waned in popularity since the late-1960s. The first comprehensive European exhibition on the movement, featuring many women historically excluded, opened at Copenhagen Contemporary last December. In the past decade, art historians have come to see it as a form of West Coast Minimalism dedicated to exploring the act of perception. Pashgian cites the late art historian Kirk Varnedoe: ‘When he wrote about Californian Light and Space, he said that, as opposed to New York Minimalism, “It’s all about ambiguity”.’

Pashgian, herself an art historian, with degrees from Pomona College and Boston University, recalls magical afternoons as a young girl watching light filter through the leaves of fruit trees in the family’s Altadena orchard near the San Gabriel Mountains. In summer, to avoid the inland heat, they rented cottages on the beach at Crystal Cove, near Laguna, a place she still goes to swim. ‘Georgia O’Keeffe said it was her belief that artists are fully formed by the time they are five. After that, it’s just a matter of refinement. I feel the same way because I remember visually how beautiful it was and how it was all about what the light did. I knew that the light changed because the water moved. I think that was one of my earliest and most profound memories. Whether that led me to do what I do, I have no idea, but I think it did.’

‘Lenses’ in progress in the artist’s studio

That youthful fascination with light, and the support of a talented art history professor, Seymour Slive, led her to study 17th-century Dutch painters, especially Vermeer. But in 1958, instead of completing a PhD at Harvard, she chose to become an artist. (‘James Turrell, who is a close friend of mine, said he thought the most interesting part of his art history class was the effect of light coming from the projector.’) She returned to Southern California – in part because of the crystalline quality of light that originally had given birth to the Hollywood film industry – and began developing her own artistic language.

Pashgian’s first abstract paintings used 17th-century glaze techniques in oil. Once she discovered polyester resin, however, it became an all-consuming quest. Declassified after the Second World War, when it had been used by aerospace engineers, the liquid plastic became widely available in the 1960s. Pashgian, like others, saw that it could emulate the clarity of atmosphere or waves. She worked with engineers to find stable epoxies and often uses urethane, despite the fact that it contains cyanide. She continues working with scientists and fabricators to improve her own formulas.

It was a 2012 studio visit from LACMA director Michael Govan that gave impetus to her shift to ambitious scale and experiments with light. After looking at the 120ft-long installation for her LACMA show, he said: ‘It seemed a totally new direction. It was like nothing anyone had seen before in terms of her work.’ That show of support drove her to create the most ambitious yet least tangible art of her life. ‘Helen spent all this time on materials,’ observed Govan, ‘and the net result is that the material disappears, and you are left with the phenomena of light and the emotion it has conjured.’

Detail of an untitled 2021 work by Helen Pashgian

For many years, Pashgian created modest globes that contained mysterious small shapes within; they required concentration and intimacy. Her latest works are the opposite. Though substantial in scale, they almost completely disappear in the cycle of her timed lighting. In a way, she is moving into the realm of pure atmosphere. As poet and critic John Yau wrote in her 2021 monograph: ‘It speaks to that deepest and oldest human experience – astonishment.’

Pashgian takes me into another room of her studio to experience her most recently completed lens, leaving me alone with my thoughts. The sculpture is there, somewhere. As the lights go down, the art defines the limits of visual knowledge, a disorientation at odds with the gentle pulsing of pastel colour. It was a feeling so foreign to contemporary existence that, despite its state-of-the-art technology, the piece embodies nothing so much as the absence of time. It is, indeed, a space that no GPS could map.

To celebrate International Women’s Day, we have released this exclusive profile as a digital first, ahead of the April 2022 issue of Wallpaper* hitting newsstands on 10 March. Pashgian also created the issue’s limited-edition cover, which is available to Wallpaper* subscribers. To get full details of our issues delivered directly to your inbox, subscribe to our newsletter, and ensure you never miss out on the latest news, features, and reviews from Wallpaper* magazine.

A series of Helen Pashgian’s ‘Lenses’ in progress in her Pasadena studio. The moulds have been filled with urethane and left to dry

Detail of an untitled 2021 work

Portrait of artist and Light and Space movement pioneer, Helen Pashgian

Helen Pashgian: ’Presences’, Installation view, SITE Santa Fe, New Mexico, until March 27, 2022. Courtesy the artist; SITE Santa Fe, New Mexico; and Lehmann Maupin, New York, Hong Kong, Seoul, and London

Helen Pashgian: ’Presences’, Installation view, SITE Santa Fe, New Mexico, until March 27, 2022. Courtesy the artist; SITE Santa Fe, New Mexico; and Lehmann Maupin, New York, Hong Kong, Seoul, and London

Helen Pashgian: ’Presences’, Installation view, SITE Santa Fe, New Mexico, until March 27, 2022. Courtesy the artist; SITE Santa Fe, New Mexico; and Lehmann Maupin, New York, Hong Kong, Seoul, and London

Helen Pashgian: ’Presences’, Installation view, SITE Santa Fe, New Mexico, until March 27, 2022. Courtesy the artist; SITE Santa Fe, New Mexico; and Lehmann Maupin, New York, Hong Kong, Seoul, and London

Helen Pashgian: ’Presences’, Installation view, SITE Santa Fe, New Mexico, until March 27, 2022. Courtesy the artist; SITE Santa Fe, New Mexico; and Lehmann Maupin, New York, Hong Kong, Seoul, and London

INFORMATION

‘Helen Pashgian: Presences’ is at Site Santa Fe, New Mexico, until 27 March, sitesantafe.org

Helen Pashgian: Spheres and Lenses, $65, is published by Radius Books, radiusbooks.org; lehmannmaupin.com

-

Marylebone restaurant Nina turns up the volume on Italian dining

Marylebone restaurant Nina turns up the volume on Italian diningAt Nina, don’t expect a view of the Amalfi Coast. Do expect pasta, leopard print and industrial chic

By Sofia de la Cruz

-

Tour the wonderful homes of ‘Casa Mexicana’, an ode to residential architecture in Mexico

Tour the wonderful homes of ‘Casa Mexicana’, an ode to residential architecture in Mexico‘Casa Mexicana’ is a new book celebrating the country’s residential architecture, highlighting its influence across the world

By Ellie Stathaki

-

Jonathan Anderson is heading to Dior Men

Jonathan Anderson is heading to Dior MenAfter months of speculation, it has been confirmed this morning that Jonathan Anderson, who left Loewe earlier this year, is the successor to Kim Jones at Dior Men

By Jack Moss

-

Leonard Baby's paintings reflect on his fundamentalist upbringing, a decade after he left the church

Leonard Baby's paintings reflect on his fundamentalist upbringing, a decade after he left the churchThe American artist considers depression and the suppressed queerness of his childhood in a series of intensely personal paintings, on show at Half Gallery, New York

By Orla Brennan

-

Desert X 2025 review: a new American dream grows in the Coachella Valley

Desert X 2025 review: a new American dream grows in the Coachella ValleyWill Jennings reports from the epic California art festival. Here are the highlights

By Will Jennings

-

In ‘The Last Showgirl’, nostalgia is a drug like any other

In ‘The Last Showgirl’, nostalgia is a drug like any otherGia Coppola takes us to Las Vegas after the party has ended in new film starring Pamela Anderson, The Last Showgirl

By Billie Walker

-

‘American Photography’: centuries-spanning show reveals timely truths

‘American Photography’: centuries-spanning show reveals timely truthsAt the Rijksmuseum in Amsterdam, Europe’s first major survey of American photography reveals the contradictions and complexities that have long defined this world superpower

By Daisy Woodward

-

Don't miss these seven artists at Frieze Los Angeles

Don't miss these seven artists at Frieze Los AngelesFrieze LA returns for its sixth edition, running 20-23 February, showcasing over 100 galleries from more than 20 countries, as well as local staples featuring the city’s leading creatives

By Annabel Keenan

-

Sundance Film Festival 2025: The films we can't wait to watch

Sundance Film Festival 2025: The films we can't wait to watchSundance Film Festival, which runs 23 January - 2 February, has long been considered a hub of cinematic innovation. These are the ones to watch from this year’s premieres

By Stefania Sarrubba

-

What is RedNote? Inside the social media app drawing American users ahead of the US TikTok ban

What is RedNote? Inside the social media app drawing American users ahead of the US TikTok banDownloads of the Chinese-owned platform have spiked as US users look for an alternative to TikTok, which faces a ban on national security grounds. What is Rednote, and what are the implications of its ascent?

By Anna Solomon

-

Architecture and the new world: The Brutalist reframes the American dream

Architecture and the new world: The Brutalist reframes the American dreamBrady Corbet’s third feature film, The Brutalist, demonstrates how violence is a building block for ideology

By Billie Walker