Henry who?: Barbara Hepworth retrospective ’Sculpture for a Modern World’ opens at Tate Britain

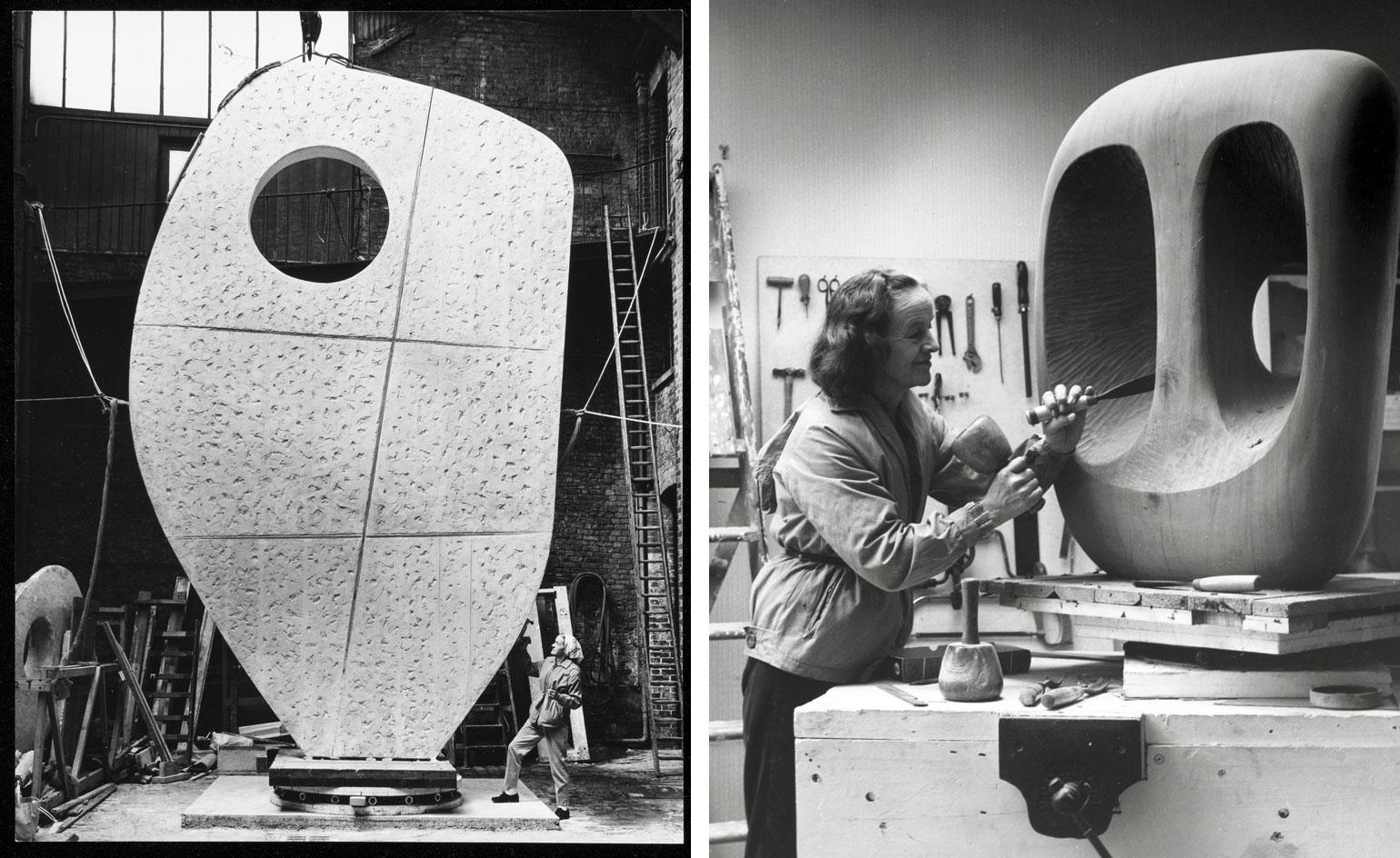

Barbara Hepworth always suffered from not being Henry Moore. Or, in fact, from not being any old Henry, John or Jacob. Sculpture being a man's business and all. Except, maybe it's not quite that simple. Certainly, Hepworth doesn't have the brand recognition that Moore does. But as a new retrospective at Tate Britain – her first for almost 50 years – makes clear, during the 1950s and 60s Hepworth was an artist of international standing in the way that Moore never really was. In 1950 she flew the flag at the Venice Biennale – and it's a Barbara Hepworth in Manhattan's UN Plaza, not a Henry Moore.

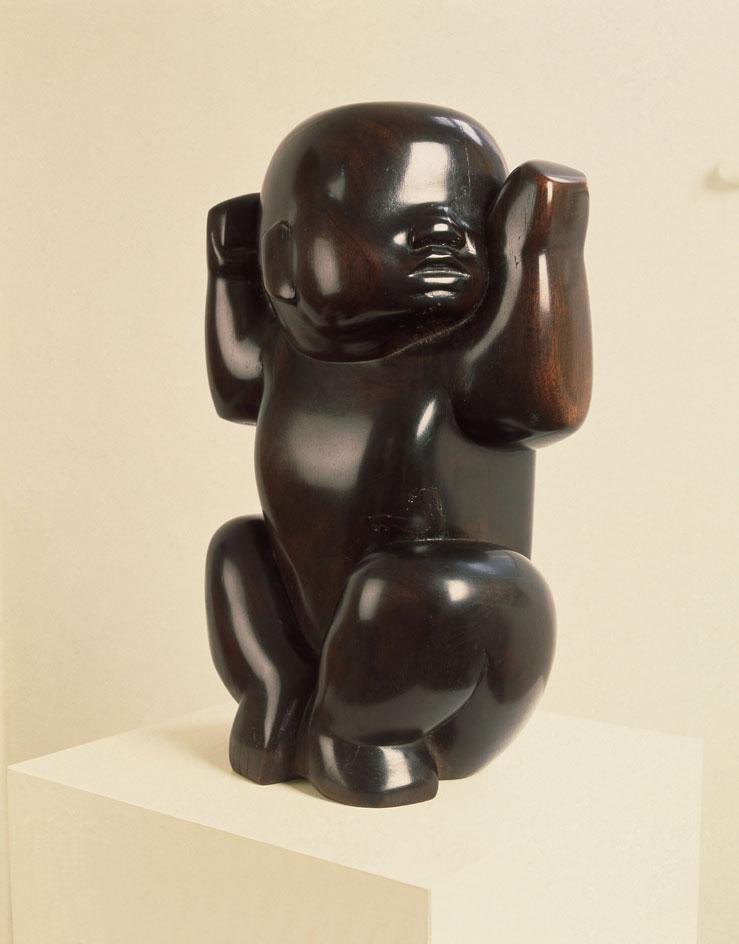

'Barbara Hepworth: Sculpture for a Modern World' is recognition that Hepworth's stock has been rising exponentially in recent years; that her abstracts now resonate more powerfully than Moore's looming figures and that her carvings in African hardwood have aged remarkably well. She certainly gets name-checked more than often than Moore these days, by designers if not artists. Hepworth is a true modernist icon in ways Moore is not.

It seems that Hepworth had planned that all along. One of the more fascinating elements of the show are her photographic collages, which first appeared in The Architectural Review in 1939, placing her works alongside modernist houses by the likes of Neutra. This now feels like a very smart move, positioning her work as part of the broader modernist project (and ensuring that she is now fetishised by the same people who fetishise Case Study Houses and Finn Juhl sofas). Indeed, the exhibition makes clear how much care and attention Hepworth – the toughest of cookies – paid to show her work was well represented in art magazines and beyond.

Another joy of the show is a room dedicated to the marvelous Gerrit Rietveld Pavilion at the Kröller-Müller Museum in Otterlo, Holland, which has housed a permanent installation of Hepworth's work since 1965. For this exhibition, Tate Britain worked with architect Jamie Fobert and students of the RCA to create a temporary take on the Pavilion, housing six works from the late 1950s and early 60s.

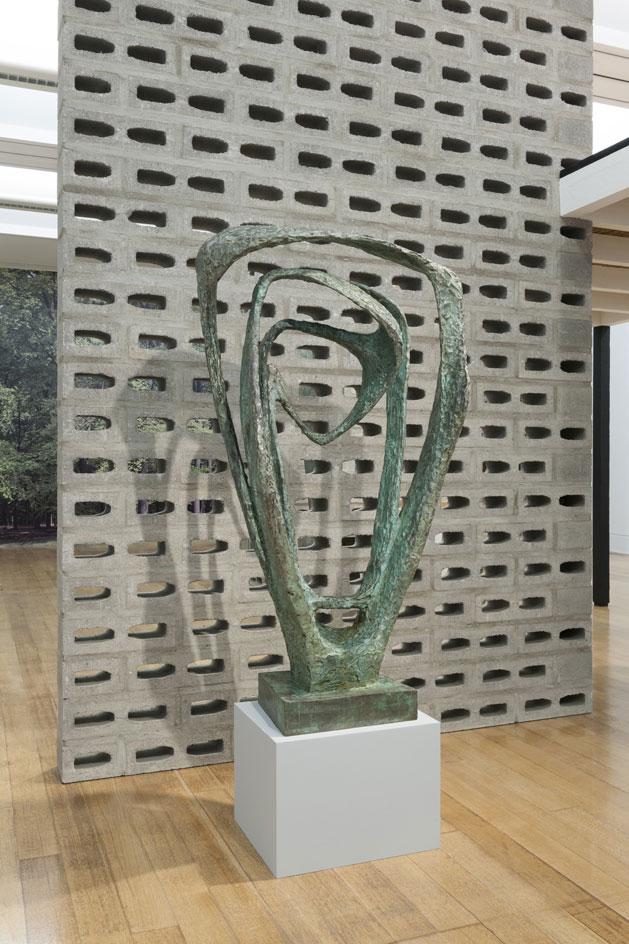

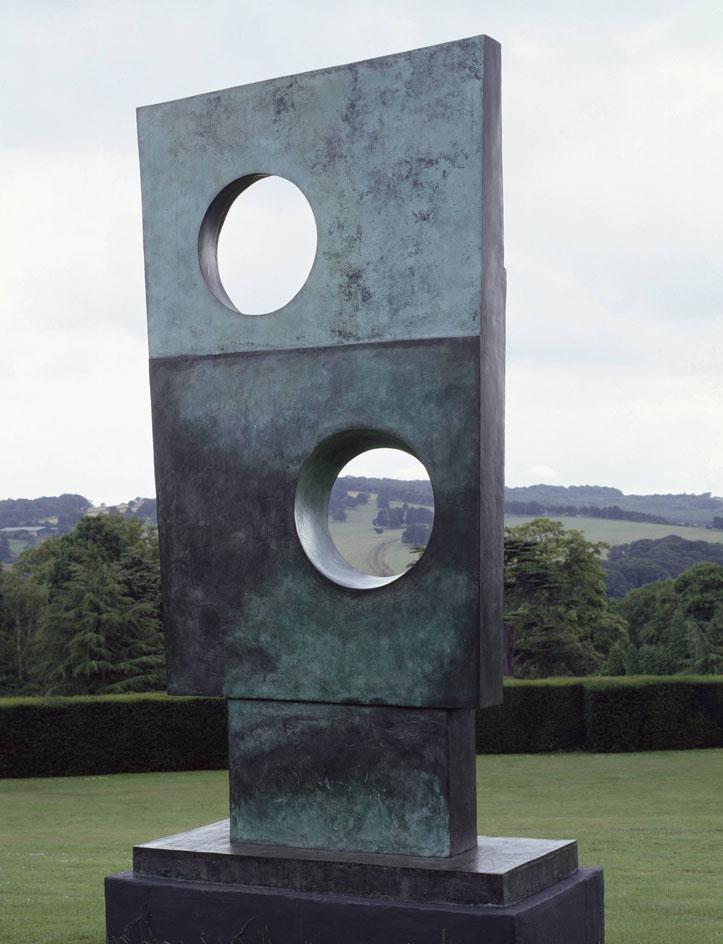

The retrospective displays over 100 artworks, including both her most significant sculptures in wood, stone and bronze, and lesser-known works.

With round and sensuous shapes carved directly into heavy materials, Hepworth created a form of raw serenity.

Powerfully evocative, Hepworth's sculptures nonetheless remain essential in form. Dove, for instance, adopts the shape of a modernist harp.

'Barbara Hepworth: Sculpture for a Modern World' is recognition that Hepworth's stock has been rising exponentially in recent years; that her abstracts now resonate more powerfully than Moore's looming figures and that her carvings in African hardwood have aged remarkably well.

The show chronologically follows Hepworth's artistic footsteps, starting out with her smaller figurative sculptures from the 1920s and culminating with the larger abstract pieces of the 1950s and 60s.

Hepworth's struggle as a woman to make it in the artistic world is an overarching theme throughout the show. Almost exclusively surrounded by men, Hepworth demonstrated a rigour in her work which seemed to exceed the desire to create and further suggested a motivation to break through.

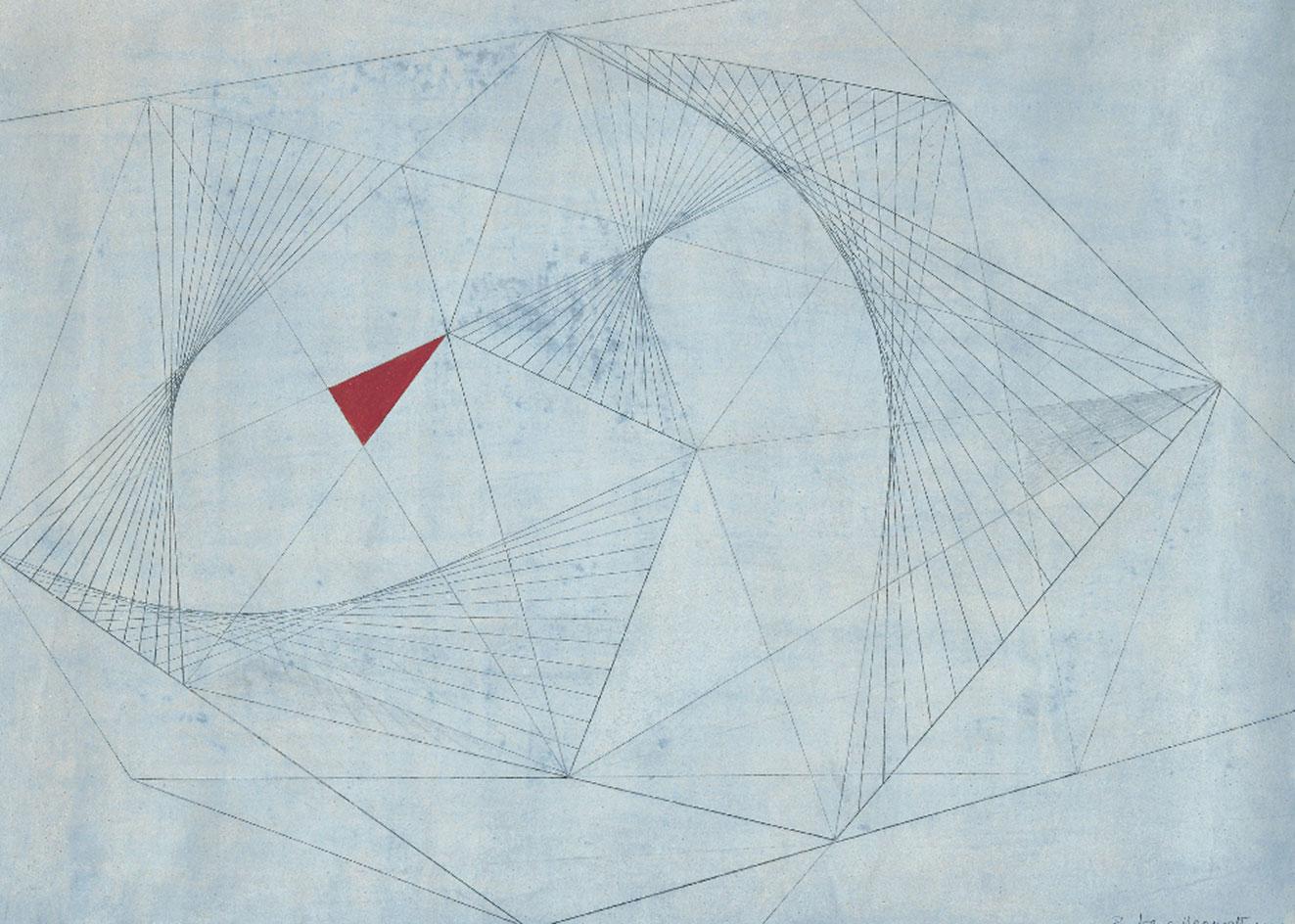

The show contains contextual multimedia such as magazines and photographs to complement the artist's work, and demonstrate its critical reception over the years.

Sketches also surround the material manifestations of her work, so as to demonstrate her creative process.

Oval Form (Trezion) was made in 1961 – 63: the years in which she more consistently created large, abstract sculptures.

Hepworth's works were meant to exist outside as environmental installations. 'All my sculpture comes out of landscape,' she wrote in 1943.

Hepworth's retrospective at Tate Britain emphasises the importance and meaningful endurance of her works.

ADDRESS

Tate Britain

Millbank

London, SW1P 4RG

Wallpaper* Newsletter

Receive our daily digest of inspiration, escapism and design stories from around the world direct to your inbox.

-

All-In is the Paris-based label making full-force fashion for main character dressing

All-In is the Paris-based label making full-force fashion for main character dressingPart of our monthly Uprising series, Wallpaper* meets Benjamin Barron and Bror August Vestbø of All-In, the LVMH Prize-nominated label which bases its collections on a riotous cast of characters – real and imagined

By Orla Brennan

-

Maserati joins forces with Giorgetti for a turbo-charged relationship

Maserati joins forces with Giorgetti for a turbo-charged relationshipAnnouncing their marriage during Milan Design Week, the brands unveiled a collection, a car and a long term commitment

By Hugo Macdonald

-

Through an innovative new training program, Poltrona Frau aims to safeguard Italian craft

Through an innovative new training program, Poltrona Frau aims to safeguard Italian craftThe heritage furniture manufacturer is training a new generation of leather artisans

By Cristina Kiran Piotti

-

Never-before-seen Barbara Hepworth works go on show in landmark exhibition

Never-before-seen Barbara Hepworth works go on show in landmark exhibitionIn ‘Barbara Hepworth: Strings’, various Hepworth sculptures will be exhibited in public for the first time, at Piano Nobile, London

By Anna Solomon

-

From activism and capitalism to club culture and subculture, a new exhibition offers a snapshot of 1980s Britain

From activism and capitalism to club culture and subculture, a new exhibition offers a snapshot of 1980s BritainThe turbulence of a colourful decade, as seen through the lens of a diverse community of photographers, collectives and publications, is on show at Tate Britain until May 2025

By Anne Soward

-

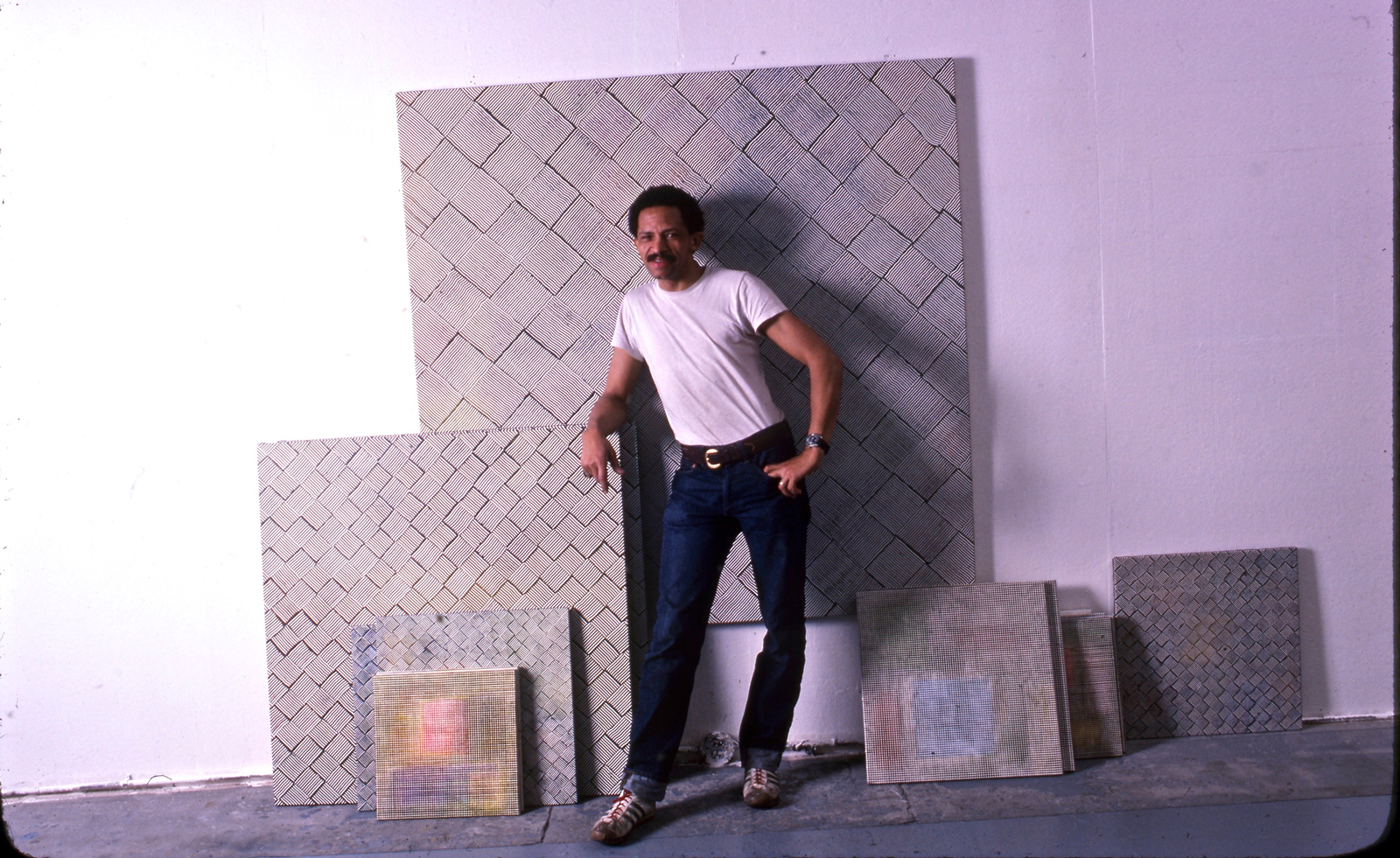

Inside Jack Whitten’s contribution to American contemporary art

Inside Jack Whitten’s contribution to American contemporary artAs Jack Whitten exhibition ‘Speedchaser’ opens at Hauser & Wirth, London, and before a major retrospective at MoMA opens next year, we explore the American artist's impact

By Finn Blythe

-

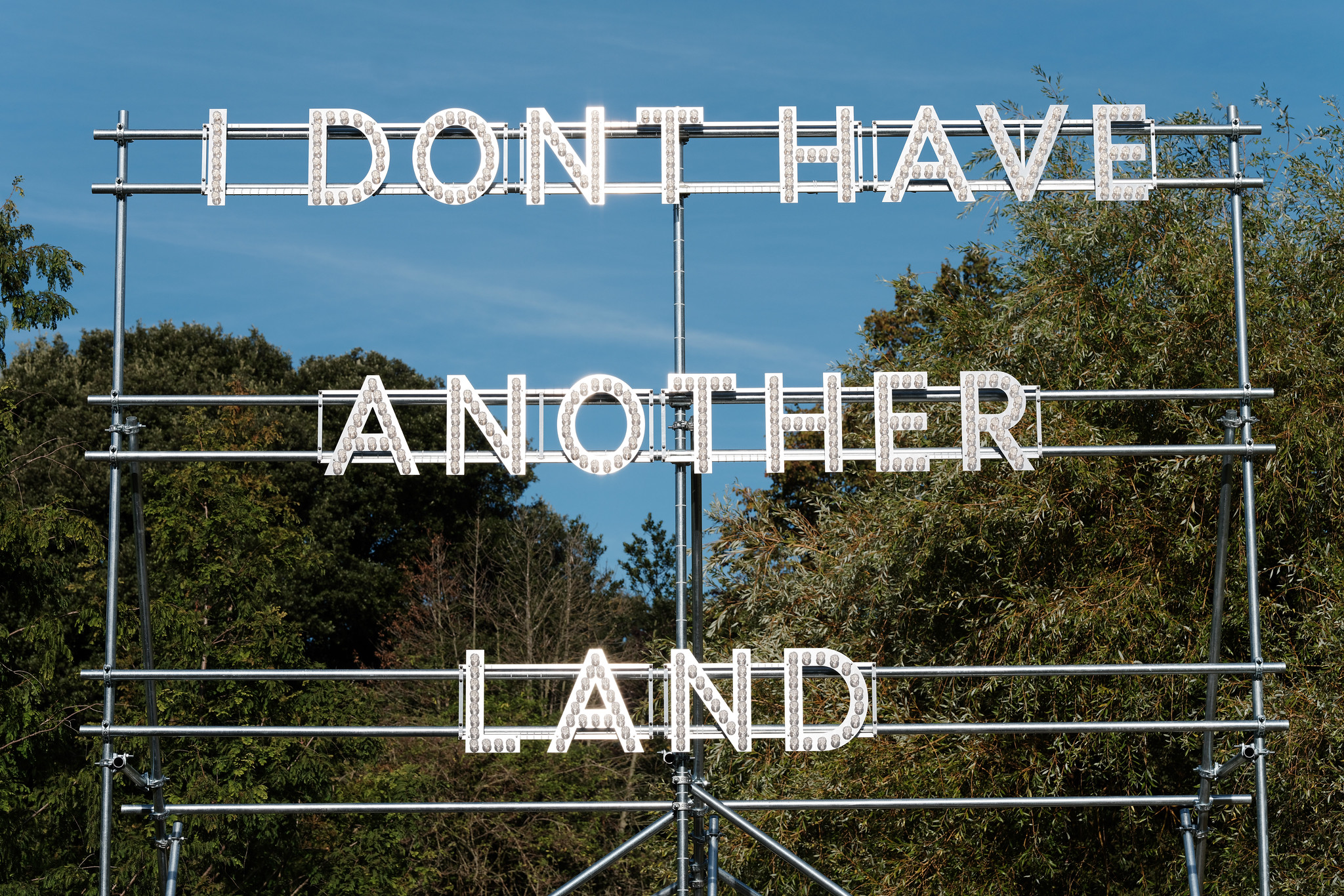

Frieze Sculpture takes over Regent’s Park

Frieze Sculpture takes over Regent’s ParkTwenty-two international artists turn the English gardens into a dream-like landscape and remind us of our inextricable connection to the natural world

By Smilian Cibic

-

Jasleen Kaur wins the Turner Prize 2024

Jasleen Kaur wins the Turner Prize 2024Jasleen Kaur has won the Turner Prize 2024, recognised for her work which reflects upon everyday objects

By Hannah Silver

-

'You survive with grace': Alvaro Barrington at the Tate Britain

'You survive with grace': Alvaro Barrington at the Tate BritainAlvaro Barrington considers Black culture with Grace installed in Tate Britain’s Duveen Galleries

By Amah-Rose Abrams

-

Harlem-born artist Tschabalala Self’s colourful ode to the landscape of her childhood

Harlem-born artist Tschabalala Self’s colourful ode to the landscape of her childhoodTschabalala Self’s new show at Finland's Espoo Museum of Modern Art evokes memories of her upbringing, in vibrant multi-dimensional vignettes

By Millen Brown-Ewens

-

Wanås Konst sculpture park merges art and nature in Sweden

Wanås Konst sculpture park merges art and nature in SwedenWanås Konst’s latest exhibition, 'The Ocean in the Forest', unites land and sea with watery-inspired art in the park’s woodland setting

By Alice Godwin