Alternative art: 'Hippie Modernism' opens at the Walker Art Center

'Hippie Modernism,' a major new exhibition at the Walker Art Center in Minneapolis, raises eyebrows as well as consciousness, yoking the tie-dye-clad, peace-and-love-preaching countercultural mascot with a movement high on more rational and precise versions of progress. This tension is at once heightened and explained by the show’s subtitle, 'The Struggle for Utopia' – a shared fight embodied by the catalogue cover image of Buckminster Fuller’s Expo 67 dome in flames.

'The Walker has always been interested in interdisciplinary things, but this show is really anti-disciplinary at its core,' says curator Andrew Blauvelt, who spent 17 years at the Center, most recently as senior curator of design, research, and publishing, before departing last month to become director of the Cranbrook Art Museum in Bloomfield Hills, Michigan. 'We wanted to look at the radical nature of these propositions, whether it’s social practice in art or speculative design out of the design sector.'

Determined to fill some historical blind spots in art, design and material culture, the show focuses on a decade that kicks off with the 1964 California-to-New York acid trip of Ken Kesey and his Merry Pranksters and concludes with the globe-spanning OPEC oil crisis. The countercultural journey unfolds according to a three-part thematic organisation borrowed from Timothy Leary – 'Turn In, Tune In, and Drop Out' – and is illuminated by Emmet Byrne’s pitch-perfect exhibition graphics and typography (this is Cooper Black’s moment to shine) that have long been a specialty of the Walker.

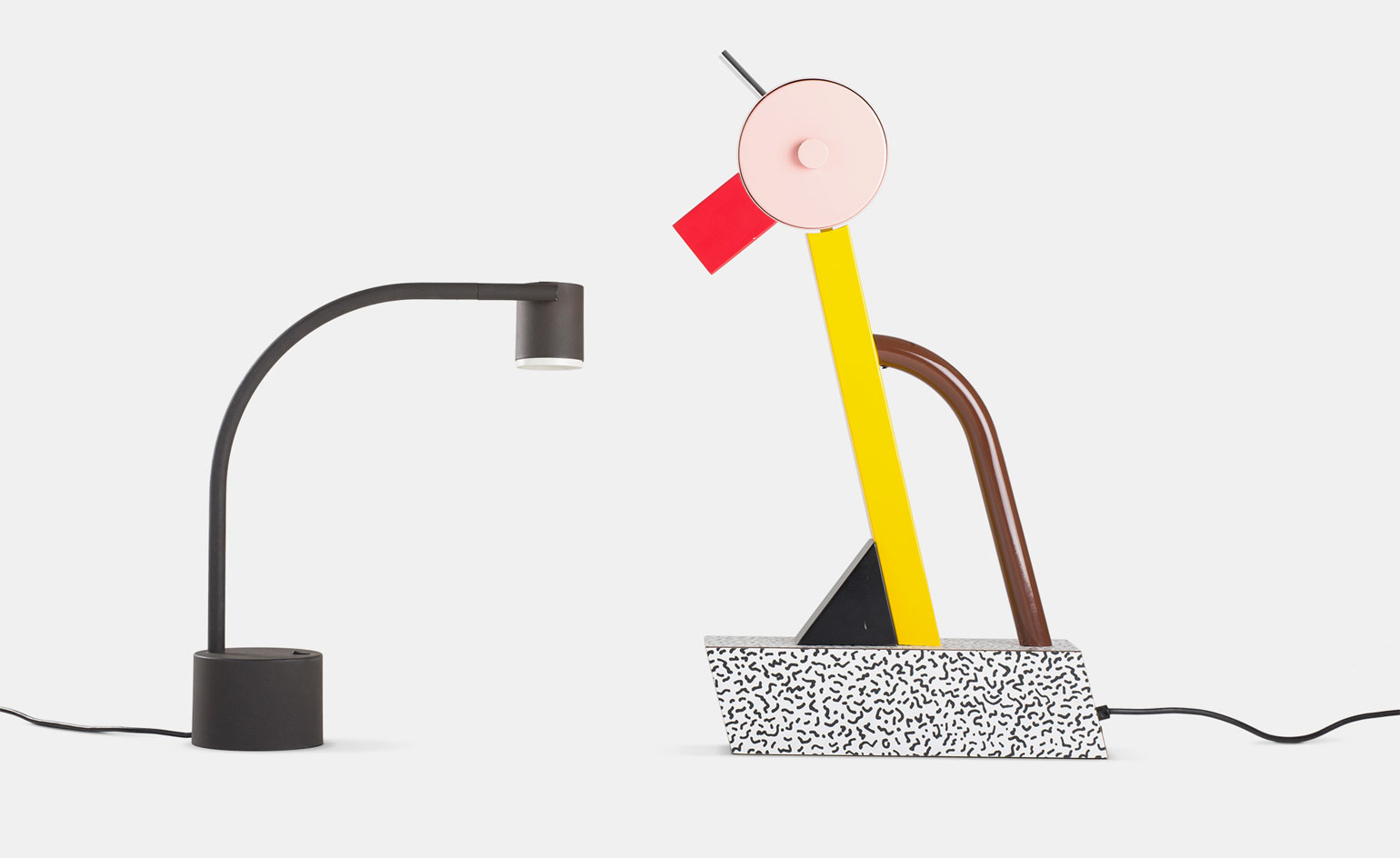

Spanning some 14,000 sq ft (1,300 sq m) of the Walker’s sublime Edward Larrabee Barnes-designed building, the exhibition opens in a psychedelic swirl of spheres, mandalas, mantras, and the altered states imagined by Ettore Sottsass in his out-of-this-world The Planet as Festival lithographs of 1971 before delving into the concepts of radical architectural groups such as Archigram and Ant Farm, who proposed better living through pods and inflatables such as Michael Webb’s 1966 'Cushicle,' which resembles the love child of a Poul Kjærholm chaise and a geodesic dome.

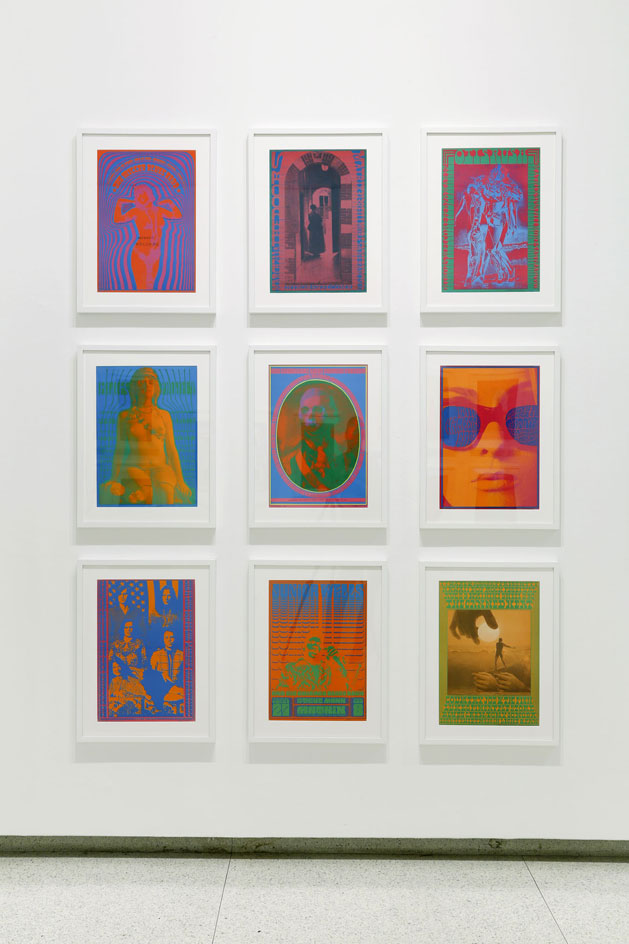

The 'Tune In' section is concerned with 'the interconnectedness of communities of interest', explains Blauvelt, who brought together original printed matter ('the Internet of its time') ranging from gig posters and protest flyers to countercultural periodicals such as Scanlan’s, a short-lived source of proto-gonzo journalism and a pioneer of infographics. An installation by Ken Isaacs immerses the viewer in images from Life and Look magazines that are projected onto six surfaces of The Knowledge Box (1962/2009), prefiguring today’s Instagram age.

The show’s final section turns its back on the mainstream, exploring the worlds of schemers and dreamers like The Cockettes, a post-Haight commune that gave birth to glitter rock. Another room is strung with the colourful hammocks of Neville d’Almeida and Helio Oiticica’s 1973 take on a Hendrix experience (lounging is encouraged), while the knitted dwelling of fibre artist Evelyn Roth is positioned not far from a copy of Computer Lib, the 1974 book in which Ted Nelson introduces the concept of hypertext and the 'deeply intertwingled' nature of personal computing.

The big finish is Newton and Helen Mayer Harrison’s Portable Orchard: 18 semi-dwarf citrus trees growing in hexagonal wooden boxes under artificial lights. The installation recreates a 1972 work undertaken by the Harrisons in California as a response to the rampant razing of orchards and farms to make way for suburban development. For Blauvelt, their 'cybernetic orange grove' is one more example of the transient reconciliation between the hippie and the modernist: a crossing of divergent paths, both bound for utopia. 'On the one hand it looks almost like a minimalist installation,' he says, walking amid the fragrant trees. 'But on the other hand it has everything to do with concerns about planetary survival.'

'The Walker has always been interested in interdisciplinary things, but this show is really anti-disciplinary at its core,' says curator Andrew Blauvelt

Included in the 'Tune In' section are protest flyers and countercultural periodicals

Also in the 'Tune In' area, this installation by Ken Isaacs immerses the viewer in images from Life and Look magazines, projected onto six surfaces of The Knowledge Box (1962/2009), prefiguring today’s Instagram age

Jimi Hendrix, by Ira Cohen, 1968.LLC

The show’s final section turns its back on the mainstream, exploring the worlds of schemers and dreamers like The Cockettes, a post-Haight commune that gave birth to glitter rock. Pictured: Untitled [the Cockettes], by Clay Geerdes, 1972.

CC5 Hendrixwar/Cosmococa Programa-in-Progress, by Neville D'Almeida and Hélio Oiticica, 1973. Collection of Walker Art Center, Minneapolis

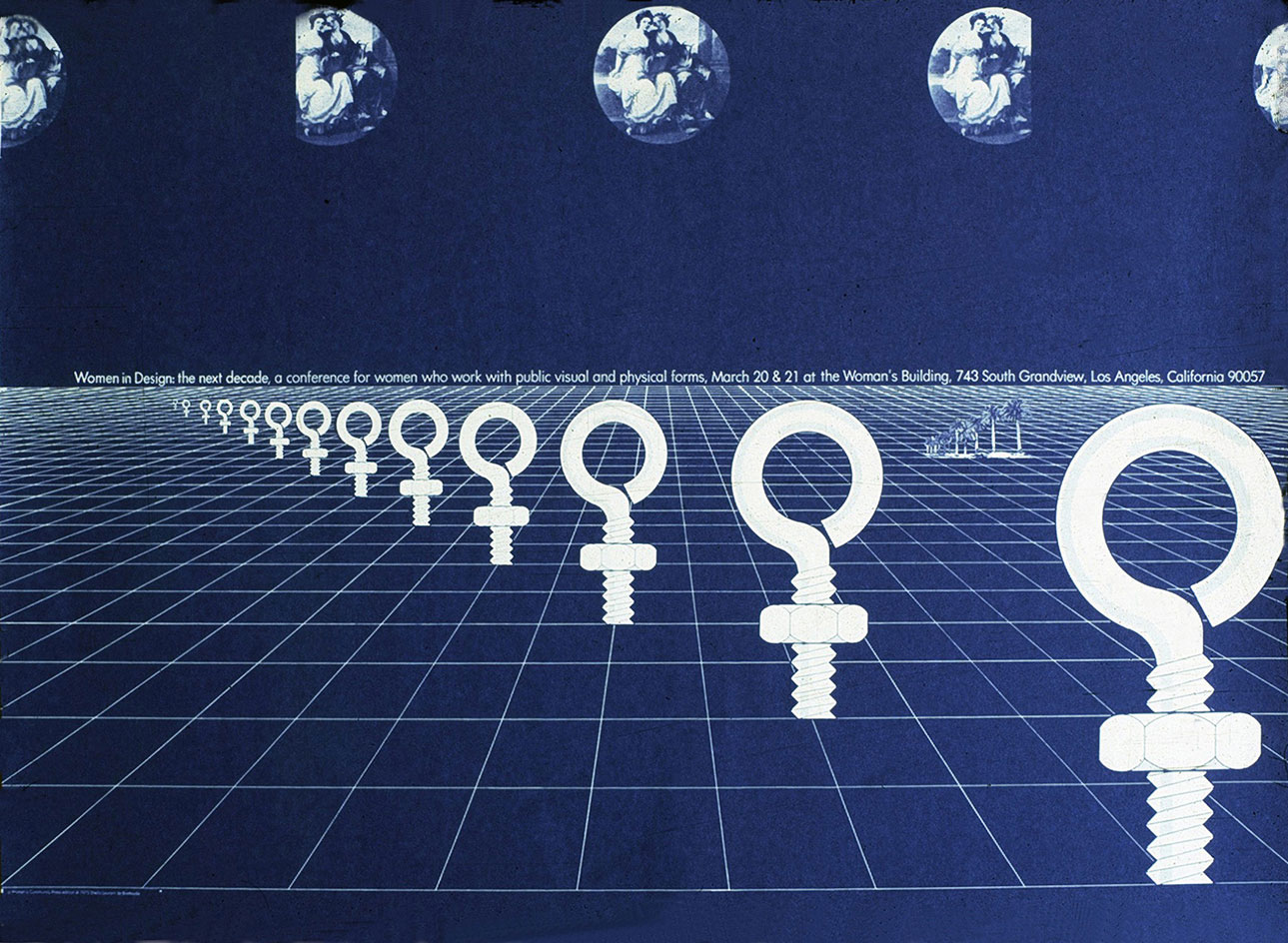

Women in Design: The Next Decade, by Sheila Levrant de Bretteville, 1975. Courtesy the artist

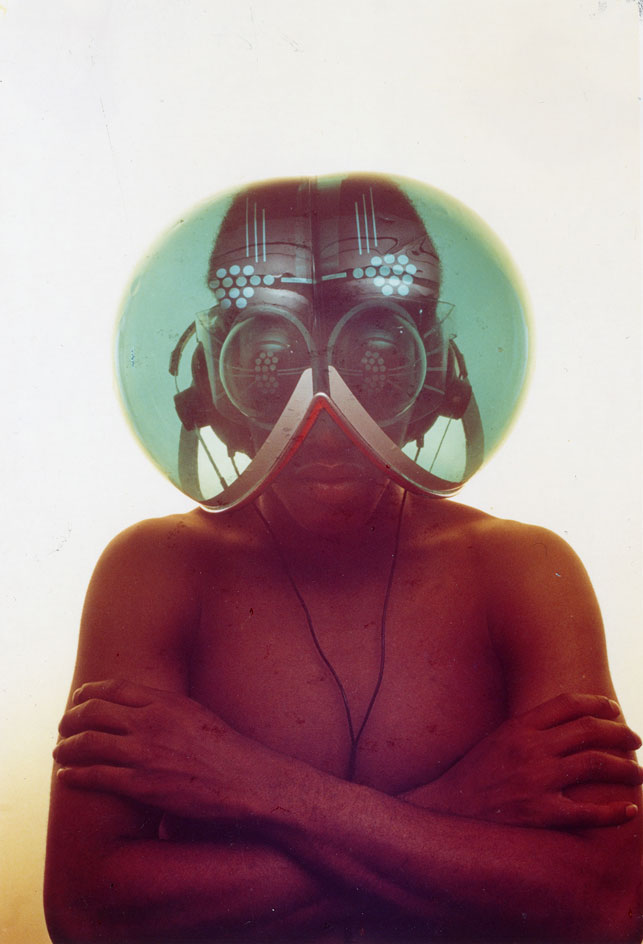

Environment Transformer/Flyhead Helmet, by Haus-Rucker-Co, 1968. Courtesy Haus-Rucker-Co, Gerald Zugmann

yellow submarine, by Corita Kent, 1967.

Superonda Sofa, by Archizoom Associati, 1966. Courtesy Dario Bartolini (Archizoom Associati)

'Hippie Modernism' is on view until 28 February 2016. Pictured: Payne’s Gray, by Judith Williams, c. 1966. Gift of Mary and Gordon Payne

INFORMATION

’Hippie Modernism’ is on view until 28 February 2016. For more information, visit Walker Art Center’s website

ADDRESS

Walker Art Center

1750 Hennepin Avenue

Minneapolis, MN 55403

Wallpaper* Newsletter

Receive our daily digest of inspiration, escapism and design stories from around the world direct to your inbox.

Stephanie Murg is a writer and editor based in New York who has contributed to Wallpaper* since 2011. She is the co-author of Pradasphere (Abrams Books), and her writing about art, architecture, and other forms of material culture has also appeared in publications such as Flash Art, ARTnews, Vogue Italia, Smithsonian, Metropolis, and The Architect’s Newspaper. A graduate of Harvard, Stephanie has lectured on the history of art and design at institutions including New York’s School of Visual Arts and the Institute of Contemporary Art in Boston.

-

Nikos Koulis brings a cool wearability to high jewellery

Nikos Koulis brings a cool wearability to high jewelleryNikos Koulis experiments with unusual diamond cuts and modern materials in a new collection, ‘Wish’

By Hannah Silver

-

A Xingfa cement factory’s reimagining breathes new life into an abandoned industrial site

A Xingfa cement factory’s reimagining breathes new life into an abandoned industrial siteWe tour the Xingfa cement factory in China, where a redesign by landscape specialist SWA Group completely transforms an old industrial site into a lush park

By Daven Wu

-

Put these emerging artists on your radar

Put these emerging artists on your radarThis crop of six new talents is poised to shake up the art world. Get to know them now

By Tianna Williams

-

Aleksandra Domanović rethinks the relationship between reality and illusion in Berlin

Aleksandra Domanović rethinks the relationship between reality and illusion in BerlinCommissioned by Audemars Piguet Contemporary, Becoming Another by Aleksandra Domanović will be on show in Berlin, 17 September – 10 October 2021

By Hannah Silver

-

Cao Fei on collective confinement and the significance of home

Cao Fei on collective confinement and the significance of homeThe Chinese multimedia artist’s new installation at the West Bund Art & Design Fair in Shanghai meditates on humanity’s capacity to unite in shared isolation

By Harriet Lloyd-Smith

-

Tomás Saraceno’s aerosolar sculptures take flight in Miami

Tomás Saraceno’s aerosolar sculptures take flight in MiamiBy Jessica Klingelfuss

-

Vitra celebrates Ettore Sottsass’ legacy as a design rebel, poet, and photographer

Vitra celebrates Ettore Sottsass’ legacy as a design rebel, poet, and photographerBy Ali Morris

-

Star turn: NYC’s Friedman Benda gallery celebrates a decade of radical design

Star turn: NYC’s Friedman Benda gallery celebrates a decade of radical designBy Pei-Ru Keh

-

Assab One’s latest show is equal to the sum of all its parts

Assab One’s latest show is equal to the sum of all its partsBy Emma O'Kelly

-

Sun Xun creates Reconstruction of the Universe for Audemars Piguet

Born in 1980, Sun Xun is among the most esteemed Chinese artists of his generation. His drawings, prints, paintings and moving images, rooted in personal memory and collective history, traverse the boundaries of art; by connecting old and new, handmade and high-tech, Eastern and Western, he creates immersive experiences in which all of the senses are activated

By Harriet Lloyd Smith

-

Gio Ponti, Studio Job and Ron Arad designs up for grabs at Sotheby's

Gio Ponti, Studio Job and Ron Arad designs up for grabs at Sotheby'sBy Sujata Burman