James Casebere imagines a near-future of flooded landscapes

Reflecting on the climate change emergency, the American photographer (and force of nature) takes us to the water's edge

Throughout his 25 year-long practice, New York-based artist James Casebere has channeled societal and political anxieties into artfully constructed photographs, from his prison images of the mid-1990s to Landscapes with Houses (2009-2011), exploring urban areas blighted by mortgage foreclosures and the ‘absurdity of living in this carbon-heavy economy’. Later, he would turn his lens to Luis Barragán’s architecture in response to rising populism, while the series The Sea of Ice (2014) reflected on climate change. ‘It always seems to work for me creatively when a personal emotional experience segues with a social or political concern,’ Casebere explains.

So to Paris, where his current exhibition at Galerie Templon, ‘On the Water’s Edge’, considers the looming threat of environmental disaster through a series of hybrid structures anchored in flooded landscapes. Recalling the impact of Hurricane Sandy and helping friends to evacuate and rebuild in its devastating wake, the artist was humbled by surfers who would brave the storm surge. ‘With that example, I contemplated designing structures as sanctuary for people at risk of displacement – temporary shelters that are a bit like hostels,’ he adds. ‘I liked that these structures could be built to withstand the storms, and could stand proudly facing the horizon on the sea.’

Nalu Tan, 2018, by James Casebere.

Each photograph is painstakingly produced in his studio: the Michigan-born artist begins by building scale models, which he then finishes with a complex lighting, colouring and image production. Here, Casebere makes a conceptual departure, taking the role of architect himself in designing and constructing these pavilions ‘of peace, where every refugee can find refuge’. It’s an homage to the dual nature of our relationship with nature: we are both vulnerable to and reliant on its power.

RELATED STORY

‘As I began dealing with architectural principles I realised that a number of architects had started their careers by either designing lifeguard stations (Pascal Flammer), or incorporating them into beach houses (Frank Gehry),’ he says. ‘There is something archetypal about that structure, signifying home, safety, and security, amid the unbridled forces of nature.’ Similarly, the composite ensembles evoke Paul Rudolph’s mid-century modern Florida houses, brutalist architecture, and the early 20th century Arts and Crafts movement.

Proponents of climate activism such as Greta Thunberg have done a great service in spurring debate – but what impact can artists have? And is there an audience willing to enable radical change? The topic of climate change has become as divisive as politics: Thunberg has been feted, applauded, empowered, vilified, pitied, and mocked. Casebere, however, remains undeterred. ‘The activist in me wants to say that I hope people will be inspired to face our challenges with fortitude and conviction, to be undaunted in the face of great odds, and to direct our collective energies toward dealing with the crisis,’ he says.

‘On the other hand, I have been thinking about the role of art and asking myself what can I, as an artist, accomplish? To what end do I make this work? Who and what can the work serve? Is it enough for art to bring pleasure, joy or a reprieve from suffering? Personally, I think it can do both, and it is not possible for me to proceed as an artist without addressing larger issues that concern me.’

Ultimately, Casebere is not such a doomsayer as he is a cautious optimist. ‘I hesitate to be too ambitious about this,’ he says, ‘but I feel like [On The Water’s Edge] involves a sense of playfulness and I hope people will come away with a sense of hope about our personal and collective ingenuity, resourcefulness, creativity, and resilience.’

Blue House on Water 2, 2018, by James Casebere.

Flooded Streets, 2019, James Casebere.

Bright Yellow House on Water, 2018, by James Casebere.

Orange House on Water, 2019, by James Casebere.

Dark Cube on Water, 2019, by James Casebere.

Industrial Overlap, 2019, by James Casebere.

INFORMATION

‘On the Water’s Edge’, until 7 March, Templon. templon.com

ADDRESS

Templon

30 Rue Beaubourg

75003 Paris

Wallpaper* Newsletter

Receive our daily digest of inspiration, escapism and design stories from around the world direct to your inbox.

-

All-In is the Paris-based label making full-force fashion for main character dressing

All-In is the Paris-based label making full-force fashion for main character dressingPart of our monthly Uprising series, Wallpaper* meets Benjamin Barron and Bror August Vestbø of All-In, the LVMH Prize-nominated label which bases its collections on a riotous cast of characters – real and imagined

By Orla Brennan

-

Maserati joins forces with Giorgetti for a turbo-charged relationship

Maserati joins forces with Giorgetti for a turbo-charged relationshipAnnouncing their marriage during Milan Design Week, the brands unveiled a collection, a car and a long term commitment

By Hugo Macdonald

-

Through an innovative new training program, Poltrona Frau aims to safeguard Italian craft

Through an innovative new training program, Poltrona Frau aims to safeguard Italian craftThe heritage furniture manufacturer is training a new generation of leather artisans

By Cristina Kiran Piotti

-

Contemporary artist collective Poush takes over Château La Coste

Contemporary artist collective Poush takes over Château La CosteMembers of Poush have created 160 works, set in and around the grounds of Château La Coste – the art, architecture and wine estate in Provence

By Amy Serafin

-

‘David Hockney 25’: inside the artist’s blockbuster Paris show

‘David Hockney 25’: inside the artist’s blockbuster Paris show‘David Hockney 25’ has opened at Fondation Louis Vuitton in Paris. Wallpaper’s Hannah Silver took a tour of the colossal, colourful show

By Hannah Silver

-

Jack White's Third Man Records opens a Paris pop-up

Jack White's Third Man Records opens a Paris pop-upJack White's immaculately-branded record store will set up shop in the 9th arrondissement this weekend

By Charlotte Gunn

-

‘The Black woman endures a gravity unlike any other’: Pharrell Williams explores diverse interpretations of femininity in Paris

‘The Black woman endures a gravity unlike any other’: Pharrell Williams explores diverse interpretations of femininity in ParisPharrell Williams returns to Perrotin gallery in Paris with a new group show which serves as an homage to Black women

By Amy Serafin

-

What makes fashion and art such good bedfellows?

What makes fashion and art such good bedfellows?There has always been a symbiosis between fashion and the art world. Here, we look at what makes the relationship such a successful one

By Amah-Rose Abrams

-

Architecture, sculpture and materials: female Lithuanian artists are celebrated in Nîmes

Architecture, sculpture and materials: female Lithuanian artists are celebrated in NîmesThe Carré d'Art in Nîmes, France, spotlights the work of Aleksandra Kasuba and Marija Olšauskaitė, as part of a nationwide celebration of Lithuanian culture

By Will Jennings

-

Out of office: what the Wallpaper* editors have been doing this week

Out of office: what the Wallpaper* editors have been doing this weekInvesting in quality knitwear, scouting a very special pair of earrings and dining with strangers are just some of the things keeping the Wallpaper* team occupied this week

By Bill Prince

-

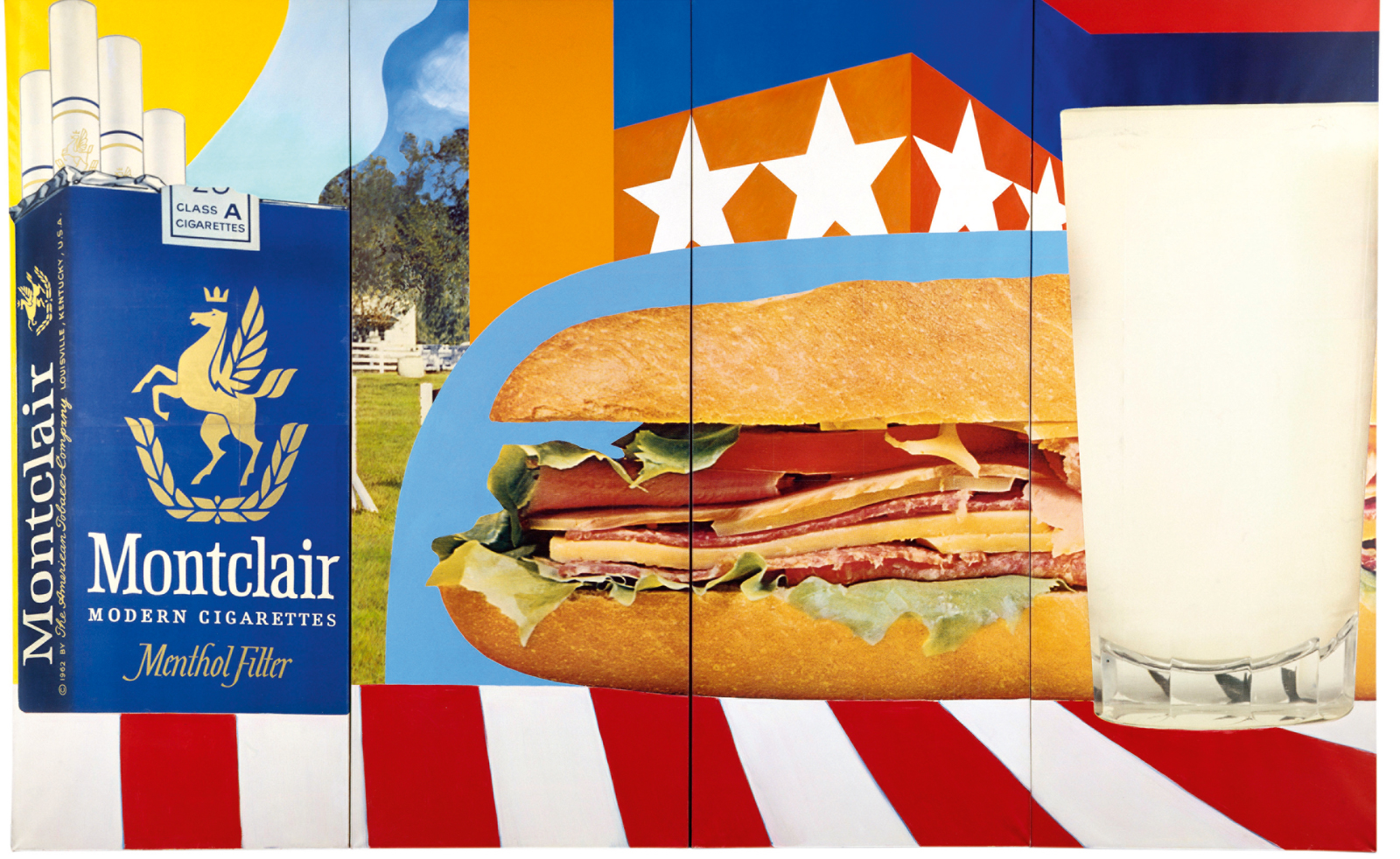

Tom Wesselmann’s enduring influence on pop art goes under the spotlight in Paris

Tom Wesselmann’s enduring influence on pop art goes under the spotlight in Paris‘Pop Forever, Tom Wesselmann &...’ is on view at Fondation Louis Vuitton in Paris until 24 February 2025

By Ann Binlot