Jean-Michel Othoniel’s gold-leaf glass sculptures herald a renaissance at the gardens of Versailles

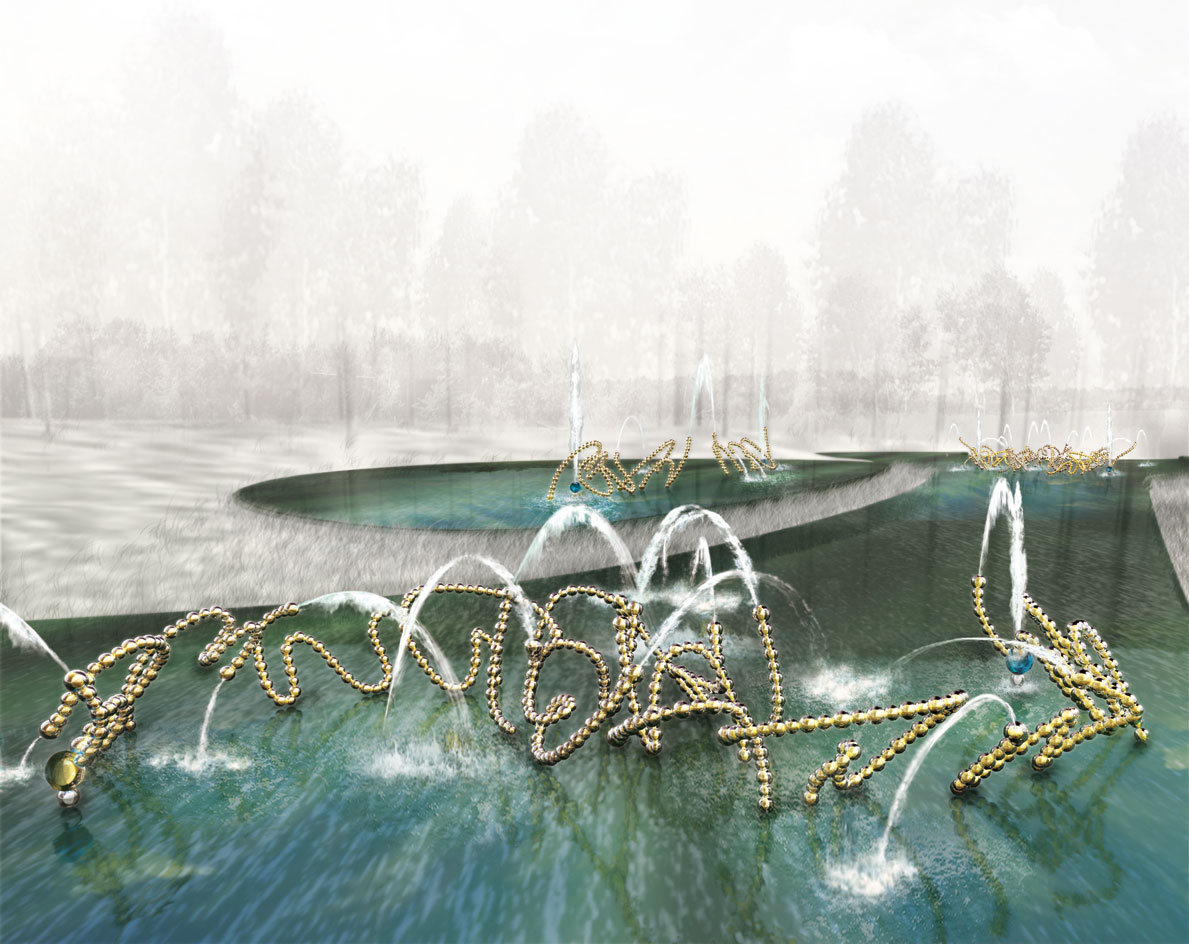

This month Louis XIV dances once again in the gardens of Versailles. In artist Jean-Michel Othoniel's three-part Les Belles Danses, water-spouting strings of gold-leaf in glass bubbles follow carefully choreographed skips, leaps and glides across three reflecting pools, inspired by ballets danced by Louis XIV. The installation, the first new permanent art created for Versailles in three centuries, marks the revival of the garden's Water Theatre grove.

The sculptures are individually tagged 'The Entrance of Apollo', 'The Rigadoun of Peace' and the 'Bourée of Achilles'. After spending much of this year working out of the palace's former apothecary, Othoniel will finish the installation this month and preview the spectacle during FIAC in October, before a grand opening next May.

The piece is based on an obscure dance annotation system developed for Louis XIV by Roger-Auger Feuillet in 1701. In a curious case of artistic synchronicity, Feuillet's startlingly modern-looking hieroglyphs were also recently rediscovered by British photographer Tessa Traeger. (You can read about how she employed them in our October issue, W*187.)

Versailles' Water Theatre grove, a setting for outdoor concerts, ballets and plays, was originally designed by Louis XIV's favoured landscape architect André Le Notre, working with the painter Charles Le Brun, and created between 1671 and 1674. It was destroyed by Louis XVI to make way for lawns and then again, and more emphatically, by the great storm of 1999.

In 2011, the Versailles estate decided it would remodel the garden and launched a competition to find a new design. Othoniel was approached by landscape designer Louis Benech, who had helped give Paris' Tuileries a facelift in the early 1990s, to join him in entering a competition.

Othoniel had experience working in the grandest of historical settings: he'd hung massive glass necklaces in the garden of the Villa Medici in Rome and installed works in the trees of the Peggy Guggenheim Collection's Venetian garden; in the Alhambra gardens in Granada; in the Mesopotamian room at the Louvre; and near the Palais-Royal. The Othoniel/Benech collaborative entry was also the only one to echo the landscaper/artist combination of the 17th century, and beat 140 competitors.

For the past two decades, Othoniel has been working with the world's finest glass blowers: in Murano in Venice, Monterrey in Mexico, Sapporo in Japan and Firozabad in India. And once he had hit upon Feuillet's annotation system, he turned to glass blowers in Murano and Basel to produce 1,750 gilded glass balls to use in his sculptures. To realize his vision, he worked with the fountain engineers of Versailles.

We talked to Othoniel about his new work and connecting with the dancing King...

W*: How did you work with Louis Benech? You hadn't worked together before?

Jean-Michel Othoniel: No, he approached me and I didn't know him, nor was I really even aware of him. But he had seen something of mine at the Pompidou. He had designed the garden stages and he asked me to work on a sculptural element, like Le Notre and Le Brun.

What condition where the gardens in before you started work?

It was a totally wild space. It had been destroyed by the storm in 1999, but it had been already destroyed by Louis XVI. It was totally overgrown and closed off to the public. It was used to store fireworks for events.

Was it hard to imagine what they had once been and what they could become?

I really wanted to link the project to Louis XIV without it becoming pastiche. I read a lot of books about him and particularly about how he used the gardens and realised that it was very choreographed. It was about theatre and dance and display. And then I found the dance annotation.

And you knew instantly that was the idea you needed? That you really had something to work with?

Yes, it seemed very close to the embroidery patterns Le Notre had made; these mazes he produced with small flowers. And there was an obvious connection for me, back to my sculptures. When I saw the annotations, they were so close to the shapes I was using in my work. They were like something from my past life. I could put them in 3D, linked to the body in movement. It was a chance to do something conceptual. The annotation was about writing down movement in space, and in a way that is close to what I try to do with my sculpture.

And you had never seen the dance annotation system before?

No. And I had the chance to read the original in the Boston library when I was doing a residency there. People in ballet knew about it but no one in art knew about it. Graphically, it looks totally contemporary. And to me it seemed to connect to artists like Richard Long and his walking art. I have tried to bring something else to it, something sensual. And also create a place and space for contemplation, much more like the English garden than the formal French garden, a place for introspection and to be in nature.

You've been at work at the former apothecary in Versailles since the beginning of the year. What was that like?

It made the scale of the project even more clear, the location and how unique it was.

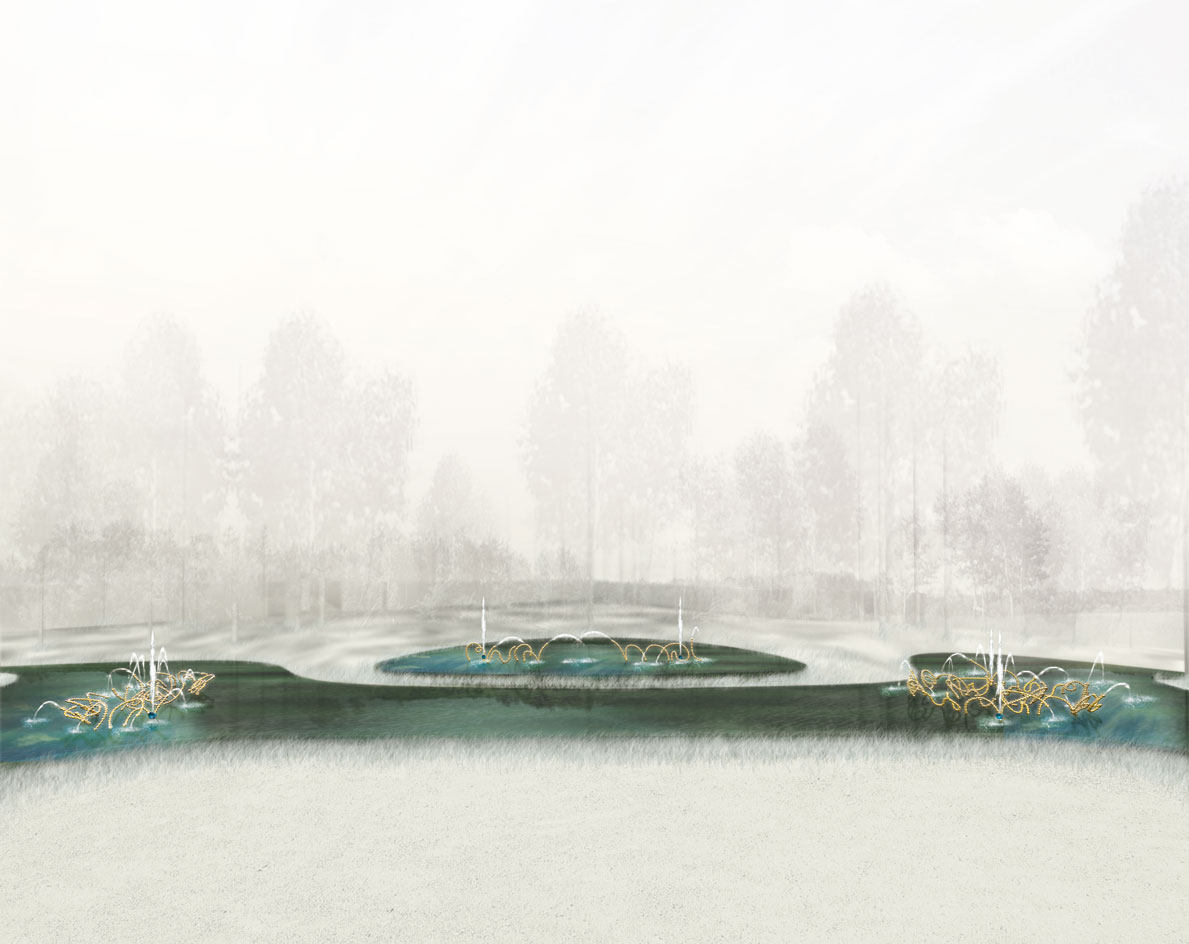

The work is based on an obscure dance annotation system developed for Louis XIV by Roger-Auger Feuillet in 1701. The artist has named them 'The Entrance of Apollo', 'The Rigadoun of Peace' and the 'Bourée of Achilles'. Photography: Philippe Chancel

He's stuffed blown-glass bubbles with gold leaf and strung them into carefully choreographed skips and leaps that will dance across the water. Photography: Philippe Chancel

The Water Theatre grove was commissioned by Louis XIV but destroyed by Louis XVI to make way for grass lawns. Those were decimated in the great storm of 1999. Othoniel's will be the first new permanent art created for Versailles in more than three centuries, and play a starring role in the revival of the grove. Rendering: Othoniel Studio

Water will spout around the gold balls to enhance the dance movements. Rendering: Othoniel Studio

The artist's watercolour sketch for the competition launched by Versailles. He submitted it in collaboration with landscape designer Louis Benech

Othoniel turned to glass blowers in Murano and Basel to produce 1,750 gilded glass balls for the sculptures. To realise his vision, he worked with the fountain engineers of Versailles

ADDRESS

Château de Versailles

Place d'Armes

78000 Versailles

Receive our daily digest of inspiration, escapism and design stories from around the world direct to your inbox.

-

How We Host: Interior designer Heide Hendricks shows us how to throw the ultimate farmhouse fête

How We Host: Interior designer Heide Hendricks shows us how to throw the ultimate farmhouse fêteThe designer, one half of the American design firm Hendricks Churchill, delves into the art of entertaining – from pasta to playlists

-

Arbour House is a north London home that lies low but punches high

Arbour House is a north London home that lies low but punches highArbour House by Andrei Saltykov is a low-lying Crouch End home with a striking roof structure that sets it apart

-

25 of the best beauty launches of 2025, from transformative skincare to offbeat scents

25 of the best beauty launches of 2025, from transformative skincare to offbeat scentsWallpaper* beauty editor Mary Cleary selects her beauty highlights of the year, spanning skincare, fragrance, hair and body care, make-up and wellness

-

Rolf Sachs’ largest exhibition to date, ‘Be-rühren’, is a playful study of touch

Rolf Sachs’ largest exhibition to date, ‘Be-rühren’, is a playful study of touchA collection of over 150 of Rolf Sachs’ works speaks to his preoccupation with transforming everyday objects to create art that is sensory – both emotionally and physically

-

Architect Erin Besler is reframing the American tradition of barn raising

Architect Erin Besler is reframing the American tradition of barn raisingAt Art Omi sculpture and architecture park, NY, Besler turns barn raising into an inclusive project that challenges conventional notions of architecture

-

What is recycling good for, asks Mika Rottenberg at Hauser & Wirth Menorca

What is recycling good for, asks Mika Rottenberg at Hauser & Wirth MenorcaUS-based artist Mika Rottenberg rethinks the possibilities of rubbish in a colourful exhibition, spanning films, drawings and eerily anthropomorphic lamps

-

San Francisco’s controversial monument, the Vaillancourt Fountain, could be facing demolition

San Francisco’s controversial monument, the Vaillancourt Fountain, could be facing demolitionThe brutalist fountain is conspicuously absent from renders showing a redeveloped Embarcadero Plaza and people are unhappy about it, including the structure’s 95-year-old designer

-

See the fruits of Niki de Saint Phalle and Jean Tinguely's creative and romantic union at Hauser & Wirth Somerset

See the fruits of Niki de Saint Phalle and Jean Tinguely's creative and romantic union at Hauser & Wirth SomersetAn intimate exhibition at Hauser & Wirth Somerset explores three decades of a creative partnership

-

Technology, art and sculptures of fog: LUMA Arles kicks off the 2025/26 season

Technology, art and sculptures of fog: LUMA Arles kicks off the 2025/26 seasonThree different exhibitions at LUMA Arles, in France, delve into history in a celebration of all mediums; Amy Serafin went to explore

-

Inside Yinka Shonibare's first major show in Africa

Inside Yinka Shonibare's first major show in AfricaBritish-Nigerian artist Yinka Shonibare is showing 15 years of work, from quilts to sculptures, at Fondation H in Madagascar

-

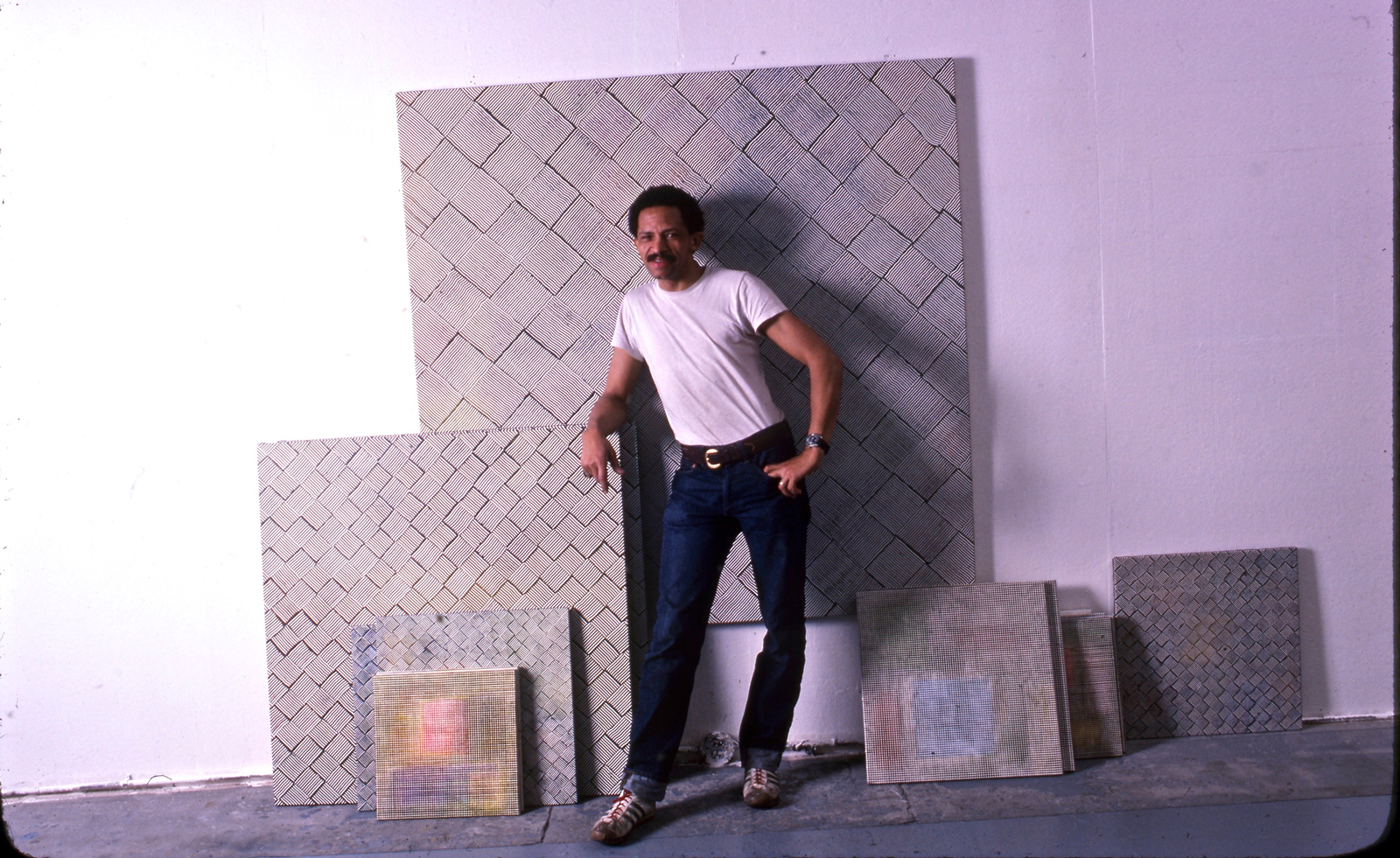

Inside Jack Whitten’s contribution to American contemporary art

Inside Jack Whitten’s contribution to American contemporary artAs Jack Whitten exhibition ‘Speedchaser’ opens at Hauser & Wirth, London, and before a major retrospective at MoMA opens next year, we explore the American artist's impact