Jeff Wall’s monumental photographs loom large at White Cube

Renowned for his meticulously composed tableaux, the Canadian artist strikes out in a new direction at the London gallery

Receive our daily digest of inspiration, escapism and design stories from around the world direct to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Few 72-year-olds can pull off shoulder-length hair, a fitted white shirt, skinny jeans and trainers. But Jeff Wall does, with aplomb. He looks like a wise old pro in a Jim Jarmusch movie. But, as witnessed in his monumental new works at White Cube Mason’s Yard in London’s St James’s, Wall’s poise in person is matched by the incredible precision of his work.

Wall is, along with Cindy Sherman, Andreas Gursky, and, slightly later, Gregory Crewdson, among the most influential conceptual photographers alive today. He grew up in Vancouver, the son of a doctor and a housewife. His parents were interested in art, and he was encouraged to be creative from an early age. ‘I was able to judge from an early age whether a piece of art was good or not,’ he says. He went through his parents’ book collection, learning about the history of artistry as a child. By his teenage years, Wall was using the local library to take out art books not available at home, and was going to galleries on his own while his friends cavorted around doing the things more typical teenagers do.

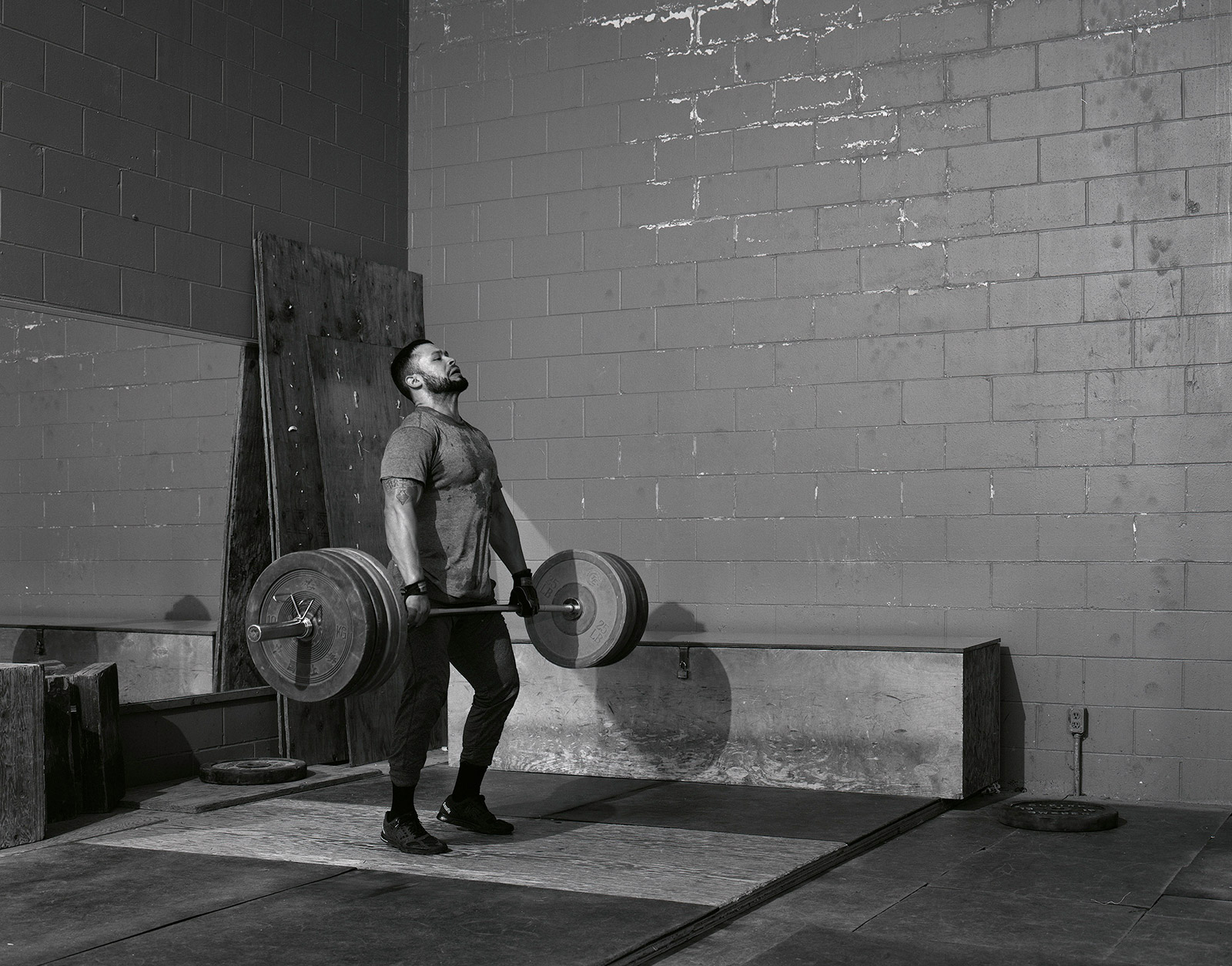

Weightlifter, 2015, by Jeff Wall, gelatin silver print.

He studied history of art at the University of British Columbia, where he fell in with a group of radically experimental artists. Wall took a while to find his voice or his chosen medium, experimenting with painting, performance and various different types of photographic imaging. But a trip to the Prado Museum in Madrid, where he genuflected to the creations of Velázquez and Goya, was significant. He remembers looking at a garishly backlit street advert he saw at a bus stop on his return home from the Prado. Wall decided he would make monumental pictures, as detailed as a Goya tableau, but with the high-production values and photorealist aesthetic of the advertising world.

Wall would soon shake the world of photography like a snow globe. Through his staged images, often painstakingly recreated from memory, or built out from an idea he happened upon, he subverted what photography was supposed to be – the act of using a camera to be a passive observer of unfolding reality, a witness to the world as it happens. His new approach caused something verging on outrage. Yet it also hooked the art world. In 2012, his work Dead Troops Talk – a meticulously staged vision created in 1992 of the moments after an ambush of a Red Army Patrol in Afghanistan – fetched just over $3.3m at Christie’s, New York, making it the third most expensive photograph ever sold at auction.

Today, he’s considered one of the godfathers of what is sometimes called ‘set-up’ photography, in which we are presented with a single image that seems stolen from a far larger, much more multivalent scenario; one unfolding either side of the moment the shutter momentarily closes, and often also happening outside of the frame. Is it real thing he witnessed, or a fiction he conjured, or a mixture of both? Wall isn’t about to provide you with an answer.

Recovery, 2017-18, by Jeff Wall, installation view at White Cube Mason’s Yard. © The artist. Courtesy of White Cube

The new show at White Cube demonstrates how restlessly Wall has worked ever since. The exhibition’s titular work is Recovery: a photorealist depiction of a young man coming to in a seaside park after, we can only presume, a fall on his bike. The image is based on years of photographs, yet it also returns Wall to the techniques he learnt as a student – that of painting. For the figures surrounding the dazed man are depicted with the ripe, vivid and off-kilter colours you might find in the expressionist movement of Paris in the first decade of the last century. The image is a ‘vision’ says Wall, a reflection of the dazed man’s mental state. But it also feels like something of a homage to the artists that have guided him, while his contemporaries were so preoccupied with exactly that – the contemporary.

Alongside Recovery hangs a triptych titled The Gardens. The three images feature arguing couples in strangely manicured but maze-like landscapes. Look closely and we realise, from one image to the next, the couples are doubles of each other. Then there’s Daybreak (2011), showing Bedouin olive pickers sleeping al fresco in the Israeli scrubland. It’s dawn, and the light is soft. They seem to be on a journey together. The image has a classical, almost Biblical quality – it could be an image from the Renaissance. Yet, on the horizon, we can see a huge secure complex, surrounded in barbed wire and white neon lights. A road leads the olive pickers to it.

Daybreak (on an olive farm/Negev Desert/Israel), 2011, by Jeff Wall.

It can seem an obvious point, but Wall’s images are huge. Recovery stretches across 4.5m of the gallery’s walls. The Gardens and Daybreak are not much smaller. This undoubtably changes the way we consider the image. A Wall image develops its own centrifugal force, sucking us in. It demands our attention, forces us to try and work out its enigmas. It’s also worth noting that the presence of a triptych is in itself something of a departure for Wall. Most photographers work in series, understanding a single subject by focusing on its many angles and sides. Wall tends to make single images, each its own construct, its own complex scenario. He creates and then presents it, avoiding any hint at his own motivations. Beyond a title, he leaves us to do the detective work.

Wall remains a student of painting, one who ‘still spends a lot of my time in galleries’. ‘If you want to be an artist, why would you not learn about the history of art,’ he says. ‘What else would you do?’ He most points out that many of the great canvas works over the centuries are ‘life-sized’. Why not a photograph? The great painters of the late 19th and early 20th century were, he points out, basically heretics, so revolutionary was their use of colour, their distortion of perspective, the lowliness of their subjects and, in Braque and Picasso’s case, the everyday objects they transformed into high art.

The photographer speaks of looking at Manet while studying at the Courtauld in the early 1970s – ‘I preferred London then,’ he says. He talks of the influence of Matisse and Gauguin and their contemporaries: of how their pursuit of Arcadia, the Greek vision of pastoralism and harmony with nature, is also his own. Wall came of age in an era when photographers spoke of the pictorial as done and disinteresting – a thing of the past. By focusing on the eternal and fertile mysteriousness of the pictorial with forensic finesse, Wall has outdone them all.

The artist. Courtesy of White Cube

Parent Child, 2018, by Jeff Wall, Inkjet print.

Hillsidenear Ragusa, 2007, by Jeff Wall, LightJet print.

The artist. Courtesy of White Cube

INFORMATION

‘Jeff Wall’, 28 June – 7 September, White Cube Mason’s Yard. whitecube.com

ADDRESS

Receive our daily digest of inspiration, escapism and design stories from around the world direct to your inbox.

White Cube

25 – 26 Mason’s Yard

London SW1Y 6BU

Tom Seymour is an award-winning journalist, lecturer, strategist and curator. Before pursuing his freelance career, he was Senior Editor for CHANEL Arts & Culture. He has also worked at The Art Newspaper, University of the Arts London and the British Journal of Photography and i-D. He has published in print for The Guardian, The Observer, The New York Times, The Financial Times and Telegraph among others. He won Writer of the Year in 2020 and Specialist Writer of the Year in 2019 and 2021 at the PPA Awards for his work with The Royal Photographic Society. In 2017, Tom worked with Sian Davey to co-create Together, an amalgam of photography and writing which exhibited at London’s National Portrait Gallery.