Jes Fan: the artist probing the intersections of biology, identity and creativity

Multidisciplinary artist Jes Fan uses fungi, bacteria and hormones to produce thought-provoking sculptures that explore how art and biology come together to break down social constructs. This article originally appeared in the August 2022 Issue of Wallpaper*, on newsstands now and available to subscribers

‘I’m not interested in technique, I’m interested in process,’ says the Brooklyn-based artist Jes Fan of his approach. Trained in the Rhode Island School of Design’s famously conceptual glass department, Fan crafts with melanin and mould as much as glass or Aqua-Resin.

In his 2019 public project for Socrates Sculpture Park in Queens, NY, for example, an interlocking resin-coated metal skeleton supported fleshy fibreglass blobs, like a body open to the air. In 2021, for the Liverpool Biennial and New Museum Triennial, Fan floated the fungus phycomyces in a maze-like grid of glass. Other projects have used squid ink, his mother’s urine, and E. coli.

Riffing on the title of the main exhibition at this year’s Venice Biennale, ‘The Milk of Dreams’, Fan looked into udders for his installation at the Arsenale. Simultaneously, he took an interest in incense, developing his own incense cones. Fan was raised in Hong Kong, a city named after the Cantonese phrase for ‘incense harbour’, perhaps due to its many aquilaria trees. When the tree is cut, it often becomes infected with fungus, causing it to secrete an aromatic resin. Such resins are referred to as ‘tears’, which led Fan to the discovery that breast milk and emotional tears share similar hormonal characteristics. ‘There’s this through line of thinking of how beauty is produced through sites of wounding or infection,’ Fan notes.

The Canadian-born, Hong Kong-raised artist Jes Fan photographed in his studio in Brooklyn, New York, in June 2022. Portrait: Jillian Freyer

His research culminated with a series of three sculptures for ‘The Milk of Dreams’, which manipulate 3D scanned and printed casts of his body. ‘There’s something that speaks to thinking about the body as an object,’ says Fan. ‘When you’re trans, you think, “My body is just a material that I can manipulate in a way”.’ Sculpting, he says, can also be a process of shedding. ‘I am someone who travels between cultures a lot and between genders a lot. I’m very sensitive to the translations required in moving from one space to another, the amount of shedding or taking on new skin.’

By removing the body from recognisability and repeating its abstracted form, Fan visualises displacement over and over again. Creating levels of removal from ‘the original’ also satisfies the need ‘to blow something up larger than life’. The resulting artworks blend the hi-tech – biochemistry and 3D scanning – with more typical contemporary sculptural and moving-image practices and millennia-tested techniques such as glassblowing.

Jes Fan, Dermal Application, 2018, pigmented silicone on gallery walls. Installation view, Jes Fan: Mother Is a Woman, Empty Gallery, 2018.Hong Kong

For his Venice sculptures, Fan initially intended to use an incense containing prolactin, the hormone that causes milk secretion in mammals. However, the damp atmosphere of the Arsenale – the former shipyard where the artwork is now on view – would hamper burning, so instead, he created a sense of flowing smoke with hormone-infused silicone. Silicone can appear skin-like, uncannily human, a facet Fan has exploited for projects such as Dermal Application (2018), which dripped flesh-toned webs of the stuff from the gallery wall. Despite its semi-organic appearance, it’s one of the earlier synthetic polymers, and is often misspelled as one of its component elements, silicon – the

basis of computer chips. ‘Craft used to be technological; back in the day, the loom was the first computer,’ Fan points out. Today’s iPhone screens, he notes, are not some purely virtual space, but rather a space mediated by glass – in Apple’s case, Gorilla Glass, which is created using a ‘cumulative knowledge’ that stretches back to early stained glass. ‘The pure present is just the constant advance of the future,’ he says. Still, he remains curious about juxtaposing ‘a sense of the ultra-handmade’ with his materials of choice, biomatter and glass.

Jes Fan, Mother of Pearl 珠, 2021, Colour print. Hong Kong

Fan’s biological practices often necessitate collaboration. For his 2018 residency at the Clinton Hill nonprofit Recess, Fan worked with firm Brooklyn Bio to use genetically modified E. coli to generate melanin, which was then placed in sculptures, displayed in lab containers. Likewise, for his Mother of Pearl series (2020-22), Fan coordinated with Yan Wa-Tat, a University of Hong Kong scientist, and Yan’s assistant William Leung, with the support of Iris Poon of Hong Kong’s Empty Gallery, to explore the potential of ‘naturally’ occurring materials generated using contemporary, lab-based methods. Fan worked with oysters to etch pearls with characters representing the colonial moniker for Hong Kong, ‘Pearl of the Orient’. ‘It’s another example of productivity or beauty occurring in sites of wounding,’ he says, noting that pearls are, in fact, a response to a foreign body being trapped in the mollusc.

A series of photos on satin of the pearls featured in the ‘Sex Ecologies’ (2021-22) exhibition at Kunsthall Trondheim in Norway, and the images will be displayed alongside the physical pearls — as well as additional incense work and a new chapbook — at ‘Sites of Wounding: Part 1’ at Empty Gallery early next year. ‘As you walk into the space, the gallery will be bisected, evoking the body of a bivalve,’ Fan explains. ‘Each sculpture will be emerging from sinuous curves from the floors or the walls, as though you have entered the body of a mollusc.’

As this species-bending project perhaps highlights, there’s a grotesqueness to his work, but there’s beauty in the grotesque. Fan plays on the tension between the repellent and the enticing, making elegant forms from matter we are conditioned to avoid – fungus, bacteria, urine, blood. Perhaps it all comes back to glass: ‘I was in a patisserie earlier and I went totally full-on hedonist,’ he says. ‘I was like, “Let’s order everything”.’ After sharing the sweets with a friend, he remarked that ‘desire is always more desirable behind glass’, from window shopping to finding dates on apps.

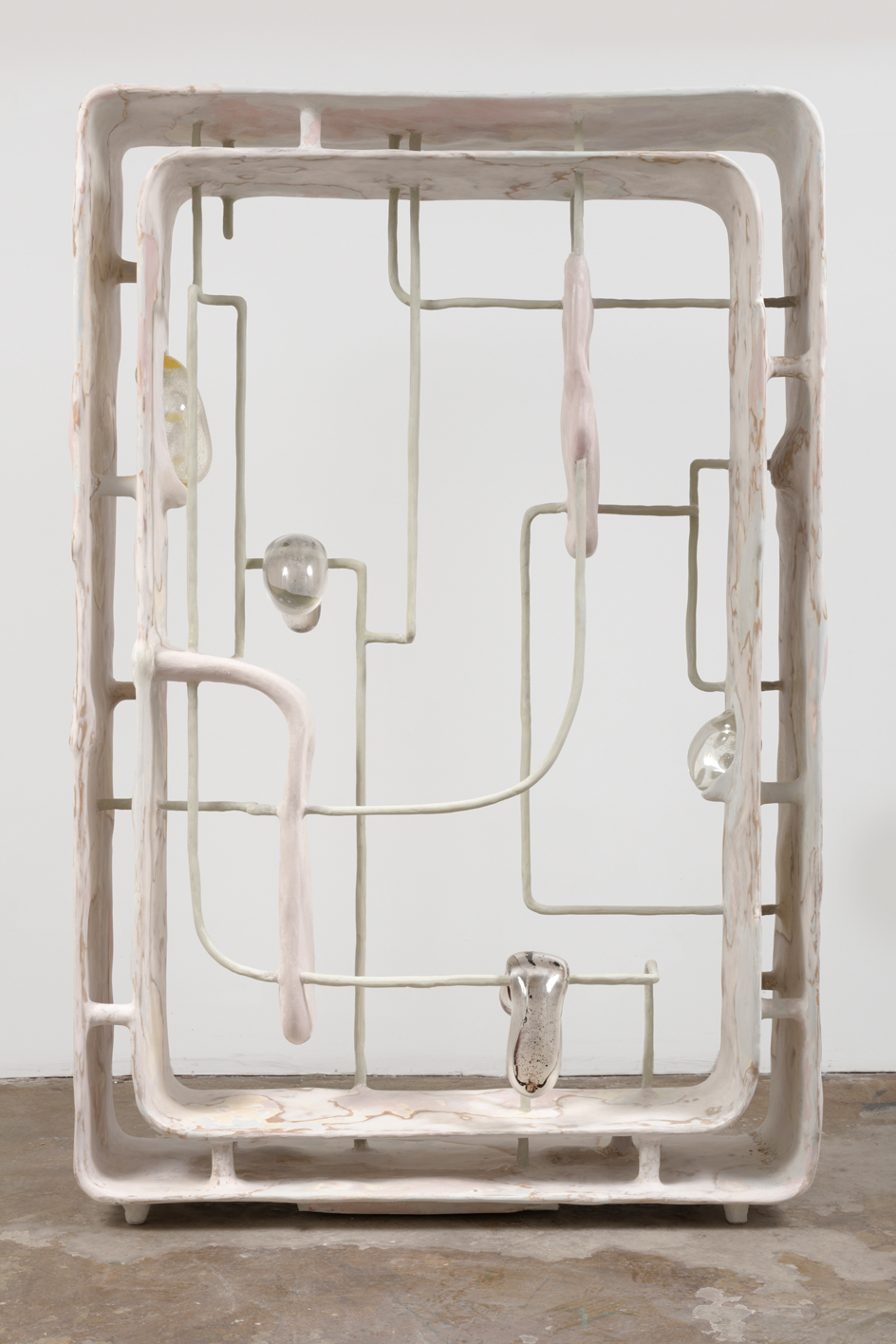

Jes Fan, Form Begets Function, 2020, Aqua resin, pigment, wood, fibreglass, glass, urine, depo-testosterone, melanin.Courtesy of the artist and Empty GalleryHong Kong.

‘There’s also something really erotic about the process of pumping these globules,’ Fan says of hand-blowing the glass bulbs that frequently appear on his sculptures. ‘The opposite pole of desire is actually fear, right? And so those are always a push and pull.’ Glass has long been used to contain and display, either as vessels or would-be invisible gateways to something else. ‘Not all of these cellular forms contain biological materials,’ he says of his amorphous glass elements. ‘But when they do, there’s something about being able to offer someone holding it a looking glass.’ He’s explored this theme with projects such as Form Begets Function (2020), which reinterpreted the scholar shelves of Chinese antiquity. Turning these display elements into the display itself, Fan’s work gives visible and tactile form to not only the content of the glass, but the glass itself. ‘There’s this word in Cantonese, shou gan, which means “hand-feeling”,’ he explains, noting that it’s similar to the academic term ‘affective haptics’, but used in everyday speech. ‘I think another aspect of my work is the relation of the handmade and the hand-feeling.’ The glass is not a frame for this other matter, rather it reveals the organising devices – be they bodily, social or technological – that corral biomatter.

In their insistent materiality, Fan’s sculptures enact a kind of reversal: shifting the category of repellent or uncanny not by making its presence more decorated, but less. ‘When you encounter the object, it looks really abstract,’ he points out. ‘Maybe that’s the ultimate truth: these highly politicised substances – melanin, but also urine, semen, blood – are actually just so abstract.’ Trying to search for some biological truth of gender or race, say, in progesterone or melanin is bald-facedly absurd: ‘What is the smallest unit of race?’ or ‘What hormones define sex and gender?’ are rhetorical questions Fan asks, to which the work rightly gives no answer: the ‘truth’ of these categories is that they are socially constructed.

Portrait: Jillian Freyer

Networks (for Expansion), and right, Networks (for Rupture), (both 2021), in borosilicate glass, silicone and phycomyces zygospore liquid culture, part of the 2021 New Museum Triennial, ‘Soft Water Hard Stone’.Hong Kong

Jes Fan, Network series, 2020–, Phycomyces zygospores, silicone, and borosilicate glass. Installation view, Liverpool Biennial: The Stomach and the Port, 2021 Courtesy of the artist and Empty Gallery; Hong Kong.

Detail from Jes Fan’s Apparatus (2022), in glass, Aqua-Resin, metal, wood and silicone. Installation view, Venice Biennale 2022, 'The Milk of Dreams'. Hong Kong

INFORMATION

‘The Milk of Dreams’ is showing until 27 November at the Venice Biennale, jesfan.com, labiennale.org, emptygallery.com

Receive our daily digest of inspiration, escapism and design stories from around the world direct to your inbox.

-

We asked six creative leaders to tell us their design predictions for the year ahead

We asked six creative leaders to tell us their design predictions for the year aheadWhat will be the trends shaping the design world in 2026? Six creative leaders share their creative predictions for next year, alongside some wise advice: be present, connect, embrace AI

-

10 watch and jewellery moments that dazzled us in 2025

10 watch and jewellery moments that dazzled us in 2025From unexpected watch collaborations to eclectic materials and offbeat designs, here are the watch and jewellery moments we enjoyed this year

-

Patricia Urquiola reveals an imaginative inner world in ‘Meta-Morphosa’

Patricia Urquiola reveals an imaginative inner world in ‘Meta-Morphosa’From hybrid creatures and marine motifs to experimental materials and textiles, Meta-Morphosa presents a concentrated view of Patricia Urquiola’s recent work

-

A forgotten history of Italian artists affected by the HIV-AIDS crisis goes on show in Tuscany

A forgotten history of Italian artists affected by the HIV-AIDS crisis goes on show in Tuscany‘Vivono: Art and Feelings, HIV-AIDS in Italy. 1982-1996’, at Centro per l'Arte Contemporanea Luigi Pecci in Prato delves into the conversation around the crisis

-

Venice Film Festival brings auteurs, daring debuts and unforgettable stories

Venice Film Festival brings auteurs, daring debuts and unforgettable storiesVenice Film Festival is in full swing – here are the films shaping up to be the year's must-sees

-

Creativity and rest reign at this Tuscan residence for Black queer artists

Creativity and rest reign at this Tuscan residence for Black queer artistsMQBMBQ residency founder Jordan Anderson sparks creativity at his annual Tuscan artist residency. Wallpaper* meets him to hear about this year's focus.

-

Rolf Sachs’ largest exhibition to date, ‘Be-rühren’, is a playful study of touch

Rolf Sachs’ largest exhibition to date, ‘Be-rühren’, is a playful study of touchA collection of over 150 of Rolf Sachs’ works speaks to his preoccupation with transforming everyday objects to create art that is sensory – both emotionally and physically

-

Architect Erin Besler is reframing the American tradition of barn raising

Architect Erin Besler is reframing the American tradition of barn raisingAt Art Omi sculpture and architecture park, NY, Besler turns barn raising into an inclusive project that challenges conventional notions of architecture

-

Photographer Mohamed Bourouissa reflects on society, community and the marginalised at MAST

Photographer Mohamed Bourouissa reflects on society, community and the marginalised at MASTMohamed Bourouissa unites his work from the last two decades at Bologna’s Fondazione MAST

-

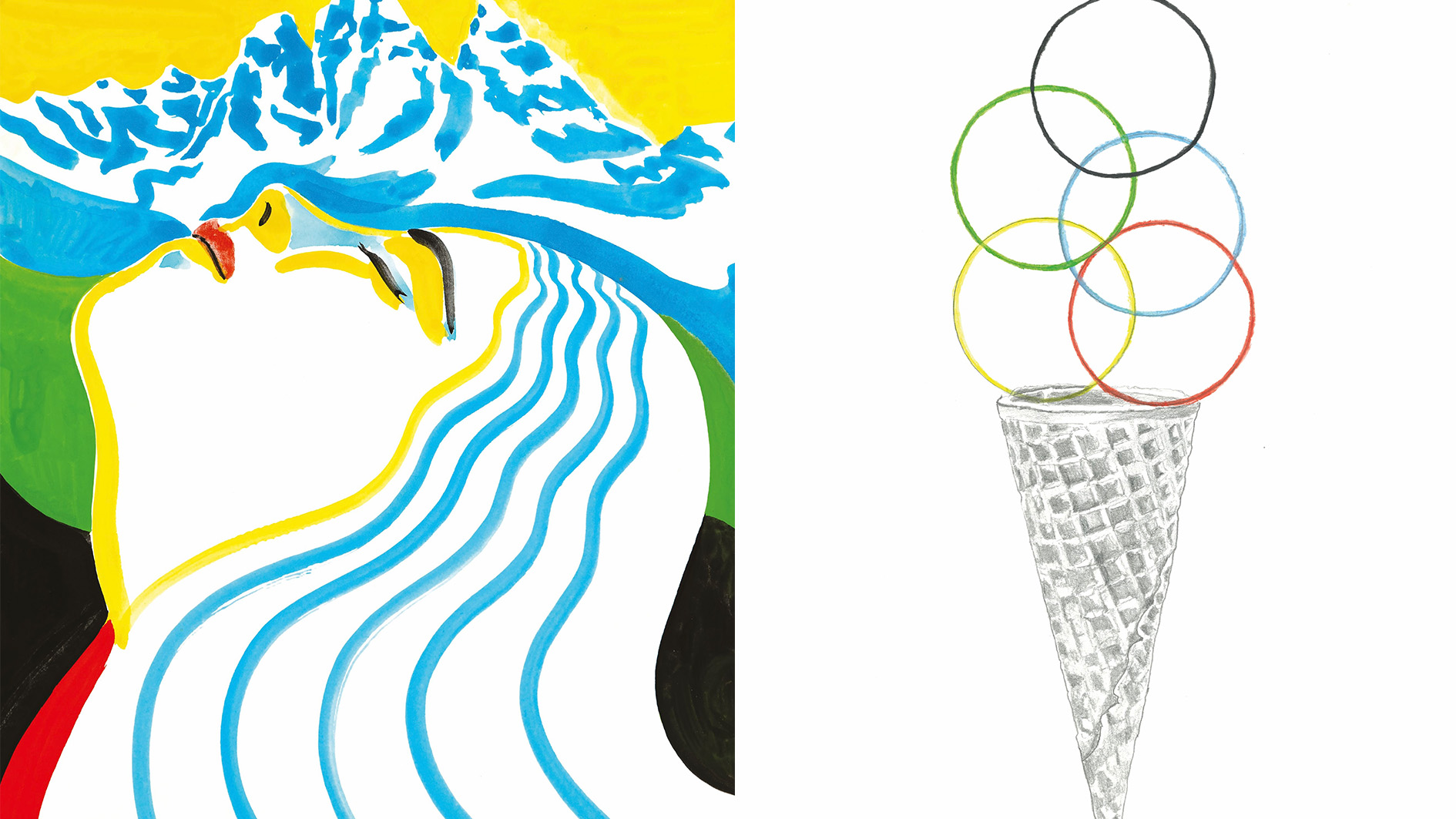

Ten super-cool posters for the Winter Olympics and Paralympics have just been unveiled

Ten super-cool posters for the Winter Olympics and Paralympics have just been unveiledThe Olympic committees asked ten young artists for their creative take on the 2026 Milano Cortina Games

-

What is recycling good for, asks Mika Rottenberg at Hauser & Wirth Menorca

What is recycling good for, asks Mika Rottenberg at Hauser & Wirth MenorcaUS-based artist Mika Rottenberg rethinks the possibilities of rubbish in a colourful exhibition, spanning films, drawings and eerily anthropomorphic lamps