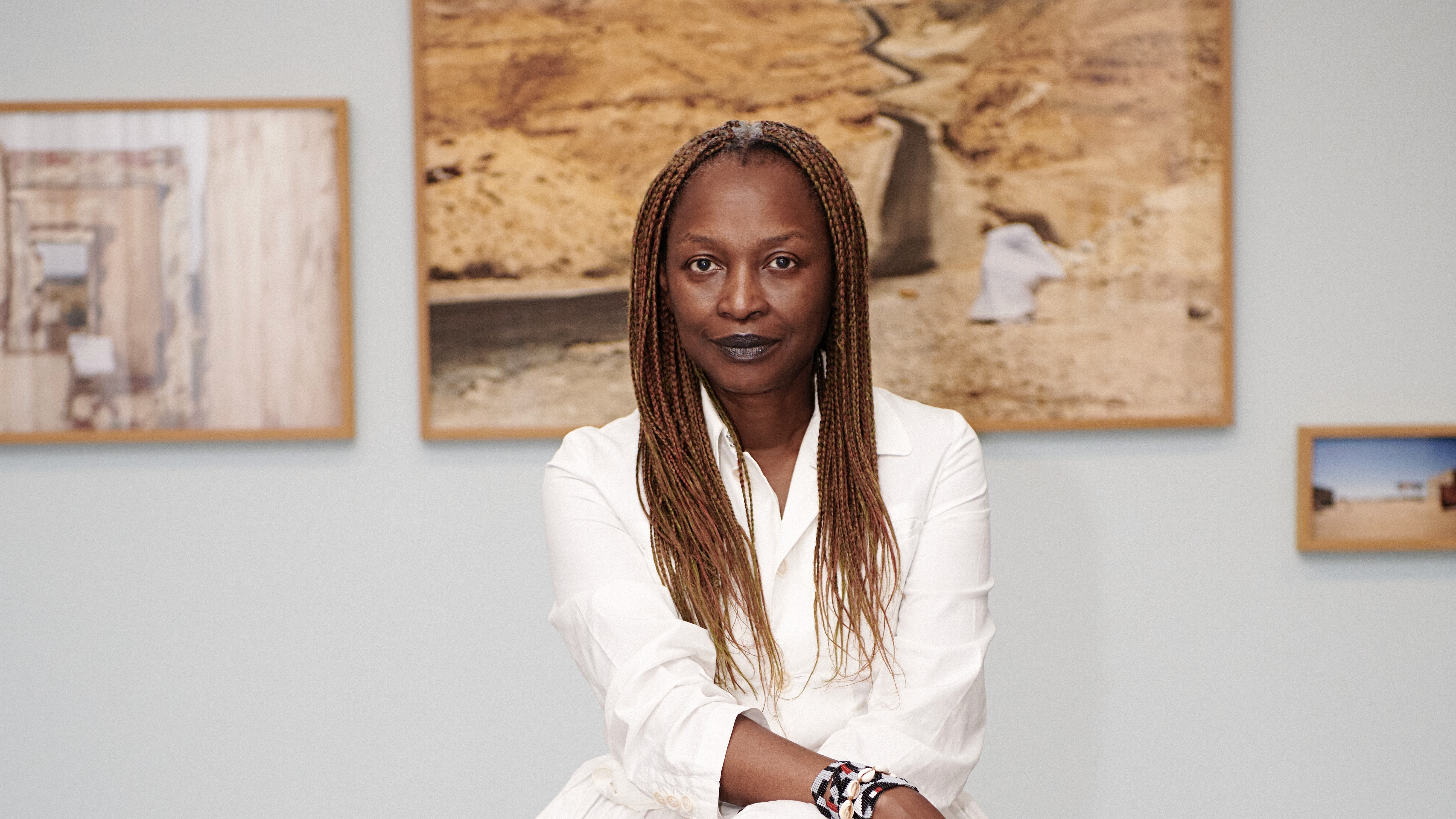

Photographer Jo Ractliffe on expanding the frame of South African documentary

‘Photographs have their own force; they push back at us’

Jo Ractliffe - Photography

When South African Jo Ractliffe emerged as a photographer in the mid-1980s, her native country was in the throes of brutal state suppression of anti-apartheid resistance. While her peers sought to document the immediacy of the violence and uprising, Ractliffe strove to widen the lens, deploying a less direct and more emblematic approach to these momentous events.

Over the following 35 years, she captured the reality and metaphors in South Africa’s national character and history, from scenes in Cape Town’s urban fringes, through the borderlands to ethereal photographs using one-dollar cameras in the port city of Durban. In 2007, she took her camera across the border to Angola to trace the aftermath of civil war. Rendered through an experimental approach to composition, technique and technology, Ractliffe's stories are told through barren landscapes fertile with allegory, roaming animals and fragments of human existence. Ractliffe’s first-ever retrospective, ‘Drives’, at the Art Institute of Chicago takes viewers on a peripatetic road trip spanning 35 years and 100 artworks.

We spoke to the photographer and videographer about the complexities of portrait photography, her influences, and using the landscape not as a subject, but as a medium.

Wallpaper*: When you began your photography practice in the mid-1980s, many of your contemporaries were capturing scenes of violence relating to state suppression of anti-apartheid resistance. Your work seemed to take a more emblematic perspective on these events. Why?

Jo Ractliffe: You’re right, South African photography, especially during the late 1970s and 1980s, was very much bound up in the work of the anti-apartheid movement - it was rooted in activism. And while I shared the concerns of fellow artists and photographers and was involved with various community organisations, when it came to my own photographic work, I felt quite complicated about things. Part of this was about a visual sensibility and, I guess, a certain temperament; I just wasn’t suited to a photography that was about advocacy. I wanted my images to expand the frame, to speak beyond the immediacy of the moment, but during a time when the requirements of photography were so clear-cut and unambiguous, such pursuits seemed to go against the grain of photographic possibility.

I began experimenting with photomontage (Nadir series 1986-88), taking my cue from John Heartfield’s War and Corpses (1932). It was quite liberating: I could reconfigure my photographs, assembling various elements from different pictures to create an image that retained something of photographic veracity but that could also speak metaphorically to what felt like an apocalyptic time in South Africa.

Jo Ractliffe, Nadir 11, 1988. Below: West Coast, 1987. © Jo Ractliffe. Courtesy of Stevenson, Cape Town and Johannesburg

W* Direct portraiture does play a role in your work, but much focuses on the traces of human existence: objects, structures, clothing and land. Why do you approach human experience and presence in this way?

JR: I’ve always experienced real discomfort when photographing people; I’m much more at ease taking long drives, working alone out in the landscape. Also in those early days, I wasn’t sure what I wanted from the portrait, which is a big problem: you have to know why you’re taking someone’s picture, what you’re doing with it. I remember photographing in Crossroads one day in 1986; this was during the State of Emergency and police and the military were patrolling the township and bulldozers were razing people’s shacks to the ground. I watched fellow photographers at work in the midst of all the craziness while I hung back and photographed the devastation left in its wake. Recently, I looked at my negative files from that day and saw that the one or two pictures I took of people have me standing behind them with the event off camera. What’s most apparent is my awkwardness; I recalled how intrusive it felt to photograph someone in the face of that kind of destruction. But photographing people remains a tricky issue for me personally; it’s not a principled thing, but I have a question about the nature of the exchange and who the work serves.

This changed somewhat when I was working on The Borderlands (2011-2013), photographing places in South Africa where people who had been dispossessed of their lands during apartheid and had lodged successful restitution claims, were finally returning home. I realised that not photographing people in these places would be akin to evicting them from their homes all over again. That changed things for me.

Jo Ractliffe, Raising the flag, Riemvasmaak, from the series The Borderlands, 2013. © Jo Ractliffe. Courtesy of Stevenson, Cape Town and Johannesburg

W*: What considerations do you make when preparing for a series of work? How much is planned, and how much is left to chance encounters?

JR: It depends on the project, but generally my work begins without too much preconception. I like to work with indeterminacy; photographing intuitively, responsively, open to the play between contingency and intention. Sometimes I’ll photograph something without specific intent, which in turn might spark a question, or I’ll remember a fragment of text or a line from a poem and so something begins. For example, the exhibition ‘End of Time’ (1999) came about when I was making an inventory of the main national road that runs from Cape Town up to the Zimbabwe border - a kind of tribute to John Baldessari’s The Backs of All the Trucks Passed While Driving from Los Angeles to Santa Barbara, Calif., Sunday 20 Jan. 63 (1963). However, on the return journey, I came across three dead donkeys lying alongside the edge of the road. They had been shot. That changed everything: what began as a simple experiment ended up being a complex work about violence and place and belonging.

W*: Why are you drawn to black and white, both aesthetically and as a vehicle to transport narratives?

JR: I started with black and white, processing and printing my work; it’s the way most photographers of my generation began. On a practical level, it was much cheaper than colour and we could take control of the whole process from developing film to printing the photograph, which you couldn’t with colour. But also - and as much as black and white is effectively an abstraction - it has a particular association with the realism of social documentary, which was the dominant practice in South Africa during the 1980s.

I have worked with colour on and off over the years, and from 2000 - 2005 I worked almost exclusively in colour for several bodies of work: Port of Entry (2000-2001), Johannesburg Inner City Works (2000-2004) and Real Life (2002-2004).

In 2006, I went back to working with black and white. I’d been wanting to break away from what had become something of a signature mode: plastic cameras, dissembled subject matter, ‘filmstrip’-like sequences. And especially when I started working in Angola, it felt very important to engage with photographic seeing more deliberately and carefully. I also wanted to get back into the darkroom, to the craft of making my prints. So you could say I’ve come full circle.

Jo Ractliffe, two figures and leaves, from the series Real Life, 2002–05. © Jo Ractliffe. Courtesy of Stevenson, Cape Town and Johannesburg

W* Throughout your career, who have been your biggest influences, in photography and elsewhere?

JR: When I first started photographing, my access to other photographers’ work was pretty limited - South Africa was quite isolated during that time and photographic books were difficult to come by. But I do remember acquiring a book called World Photography, which introduced me to great photographers like Robert Frank, Joseph Koudelka and Manuel Álvarez Bravo, to name a few. Other early influences were Chris Killip and Richard Misrach. What I saw in their work was that photography could be political and poetic and expressive all at the same time. And in Alvarez Bravo’s work particularly, things seem more than they appear to be as if he had parted the veil between the appearances of this world and what lies behind it. I love that about his work and it’s something I strive for in my images.

But I am probably more influenced by writers and poets, even songwriters - too many to list here. So much of my thinking and seeing connects with what I read. It might have something to do with the shift in medium; words activate my imagination differently from images and in almost all my work, I can see where someone’s writing has entered in.

Receive our daily digest of inspiration, escapism and design stories from around the world direct to your inbox.

Jo Ractliffe, Crossroads, 1986. © Jo Ractliffe. Courtesy of Stevenson, Cape Town and Johannesburg

W*: Your retrospective ‘Drives’ at the Art Institute of Chicago spans 35 years of your practice. Looking back, do you think your priorities or approach to image making have changed since the beginning of your career?

JR: I think my core interests and motivations - what’s at the heart of photography for me - have remained pretty much unchanged. But I think what drives us creatively often comes from stuff that’s laid down quite early on; things that shape our view or understanding of the world - at least that’s how it is for me. And as much as I may understand the world somewhat differently now from when I was in my twenties, I don’t think the world itself has changed that much. So the questions I have around violence, dispossession and loss remain at the forefront of my work. As has the landscape, which in many ways is less a ‘subject’ than it is the medium through which I can explore these issues of conflict, loss and memory.

What has changed recently is how I work with images. This is largely the consequence of a spinal injury I sustained in 2015, which has forced a different way of working from the extended photo-essay, which required a certain narrative coherence - and of course, lengthy periods of travel. Recently I’ve been going back into my negative files, exploring what happens when a selection of seemingly disparate images comes together. It’s exciting to see that photographs do have their own force; they push back at us, and if we pay attention, we can enter into different relations with them.

Jo Ractliffe, verge, from the series reShooting Diana, 1990–95, portfolio printed 2004. © Jo Ractliffe. Courtesy of Stevenson, Cape Town and Johannesburg

Jo Ractliffe, Vlakplaas: 2 June 1999 (drive-by shooting), 1999, printed 2002. © Jo Ractliffe. Courtesy of Stevenson, Cape Town and Johannesburg

INFORMATION

Jo Ractliffe, ’Drives’, until April 26, 2021, the Art Institute of Chicago

ADDRESS

The Art Institute of Chicago

111 S Michigan Ave

Chicago, IL 60603

Harriet Lloyd-Smith was the Arts Editor of Wallpaper*, responsible for the art pages across digital and print, including profiles, exhibition reviews, and contemporary art collaborations. She started at Wallpaper* in 2017 and has written for leading contemporary art publications, auction houses and arts charities, and lectured on review writing and art journalism. When she’s not writing about art, she’s making her own.

-

Wallpaper* Design Awards: Boghossian’s gem wizardry dazzles in high jewellery

Wallpaper* Design Awards: Boghossian’s gem wizardry dazzles in high jewelleryBoghossian's unique mix of craftsmanship and modern design is behind the edgy elegance of its jewellery – a worthy Wallpaper* Design Awards 2026 winner

-

Wallpaper* Design Awards: cult London fashion store Jake’s is our ‘Best Retail Therapy’

Wallpaper* Design Awards: cult London fashion store Jake’s is our ‘Best Retail Therapy’Founded by Jake Burt, one half of London-based fashion label Stefan Cooke, the buzzy, fast-changing store takes inspiration from Tracey Emin and Sarah Lucas’ 1993 The Shop and Tokyo’s niche fashion stores

-

Behind the scenes of OK Go's Grammy-nominated vinyl packaging

Behind the scenes of OK Go's Grammy-nominated vinyl packagingIndie-rock group OK Go have returned with an innovative new sound and look for their fifth album. We meet singer Damian Kulash to find out more.

-

David Goldblatt captures intimate portraits of Johannesburg during apartheid

David Goldblatt captures intimate portraits of Johannesburg during apartheidBetween 1948 and 2016, David Goldblatt returned periodically to Fietas, a suburb in the west of Johannesburg’s city centre, to photograph the impact of apartheid legislation on its residents and landscape. The resulting photographs have now been collected and published for the first time

-

Remembering Koyo Kouoh, the Cameroonian curator due to lead the 2026 Venice Biennale

Remembering Koyo Kouoh, the Cameroonian curator due to lead the 2026 Venice BiennaleKouoh, who died this week aged 57, was passionate about the furtherance of African art and artists, and also contributed to international shows, being named the first African woman to curate the Venice Biennale

-

Zanele Muholi celebrates South Africa’s Black LGBTI communities in LA and London

Zanele Muholi celebrates South Africa’s Black LGBTI communities in LA and LondonZanele Muholi's portraits and sculptures are currently on show at Southern Guild Los Angeles and the Tate Modern, London

-

Esther Mahlangu’s first retrospective features the iconic BMW 525i Art Car

Esther Mahlangu’s first retrospective features the iconic BMW 525i Art CarEsther Mahlangu showcases ‘Then I knew I was good at painting’ at the Iziko Museums of South Africa in Cape Town

-

Now Gallery presents the vibrant culture of ‘A Young South Africa’ captured through the lens

Now Gallery presents the vibrant culture of ‘A Young South Africa’ captured through the lensNow Gallery’s ‘A Young South Africa, Human Stories’ showcases six inspiring photographers for the 2023

-

Cyprien Gaillard on chaos, reorder and excavating a Paris in flux

Cyprien Gaillard on chaos, reorder and excavating a Paris in fluxWe interviewed French artist Cyprien Gaillard ahead of his major two-part show, ‘Humpty \ Dumpty’ at Palais de Tokyo and Lafayette Anticipations (until 8 January 2023). Through abandoned clocks, love locks and asbestos, he dissects the human obsession with structural restoration

-

Year in review: top 10 art interviews of 2022, chosen by Wallpaper* arts editor Harriet Lloyd-Smith

Year in review: top 10 art interviews of 2022, chosen by Wallpaper* arts editor Harriet Lloyd-SmithTop 10 art interviews of 2022, as selected by Wallpaper* arts editor Harriet Lloyd-Smith, summing up another dramatic year in the art world

-

Yayoi Kusama on love, hope and the power of art

Yayoi Kusama on love, hope and the power of artThere’s still time to see Yayoi Kusama’s major retrospective at M+, Hong Kong (until 14 May). In our interview, the legendary Japanese artist vows to continue to ‘create art to leave the message of “love forever”’