In memoriam: John Baldessari (1931-2020)

The godfather of conceptual art died on 2 January at his home in Venice, Los Angeles, at the age of 88

The artist John Baldessari worked as an abstract painter in the 1950s and 1960s, with mixed success. On a Friday afternoon in July 1970, he packed all of his paintings into his car and drove them to a funeral home in San Diego, where he lived at the time. Once there, he loaded 13 years worth of work – dated from his college graduation in May 1953 until March 1966, when he gave up relational painting – into the funeral pyre and watched as his work was cremated.

Later that summer, Baldessari moved from San Diego to Santa Monica to teach a course at the California Institute of the Arts (CalArts). Around the same time, he carefully reformed the charred and ashen remnants of his early career, baking them into cookies and placing them in an urn. He then transported the ashes to New York, where they were displayed at the Museum of Modern Art as part of ‘Information’, the museum’s seminal group show of contemporary conceptual art.

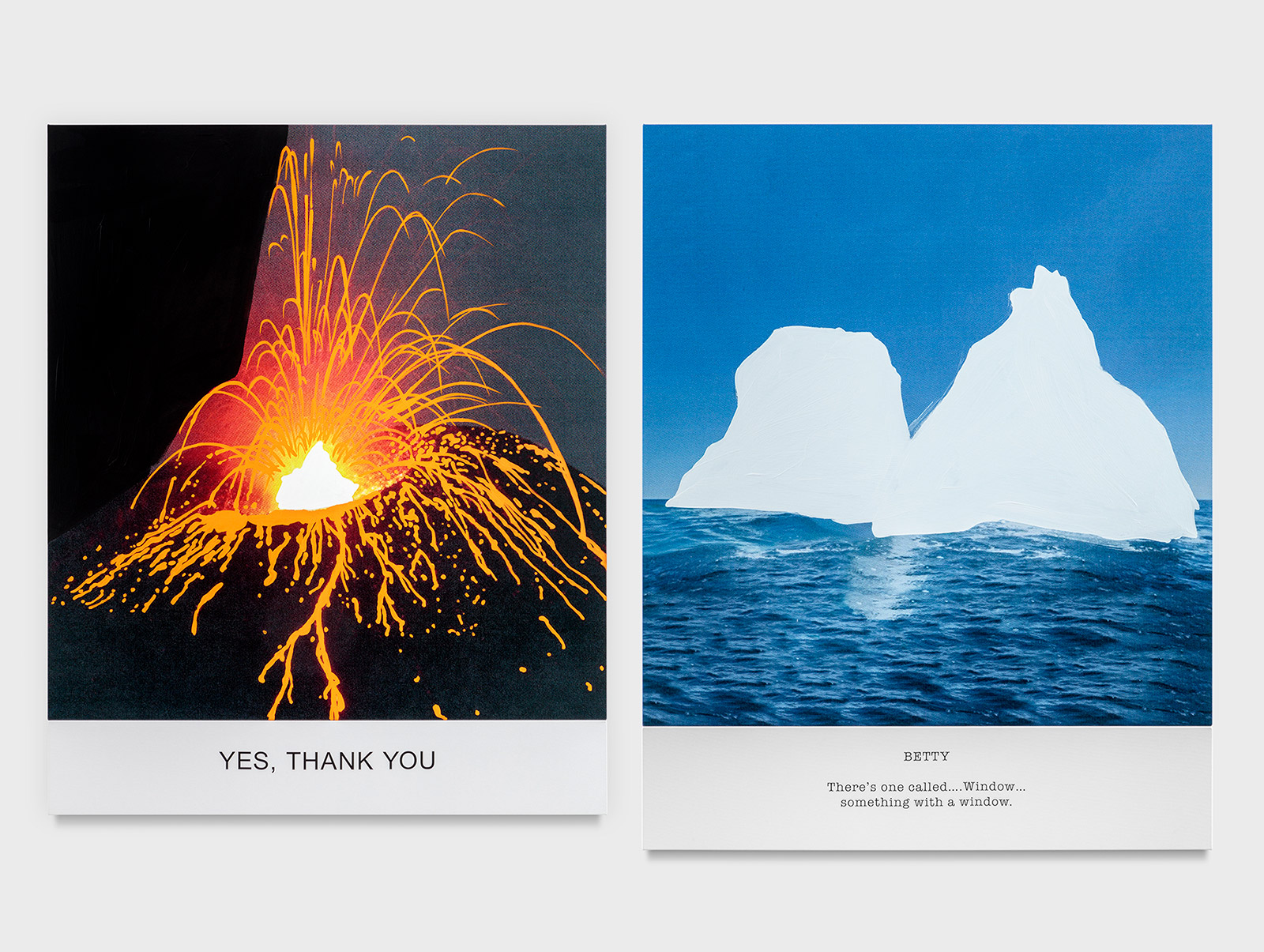

Hot & Cold Series: YES, THANK YOU, BETTY There’s one called..., 2018, varnished inkjet prints on canvas with acrylic paint. New York, Paris and London

The Cremation Project was inspired by another bastion of conceptual art, Marcel Duchamp, after Baldessari witnessed the French artist’s 1963 retrospective at the Pasadena Art Museum, curated by Walter Hopps. While Baldessari’s contemporaries approached their art with a remote, straight-faced seriousness, Baldessari learnt from Duchamp that art could be laced with satire. He was given permission to use art to tell jokes. ‘It was a very public and symbolic act,’ Baldessari later said of his dramatic act. ‘Like announcing you’re going on a diet in order to stick to it.’

Baldessari’s cremation act, alongside his move to CalArts, was a way of publicly announcing a different direction in his journey as an artist: a way of jettisoning the abstract straitjacket he had formed for himself so as to explore a practice of expansive multimedia conceptualism. At CalArts, he founded what he called his ‘post-studio’, where he worked across a range of new media – painting and text, video and photography, sculpture and installation. In doing so, Baldessari started on a path of experimentation that, by the time of his death, would see him garlanded as one of the most influential contemporary American artists and educators of the late-20th century – and, along with Ed Ruscha, California’s art heavyweights of the era.

Baldessari and Ed Ruscha, pictured at Ruscha’s studio in Culver City. (See their pick of LA’s brightest creative talents here.)

Baldessari was born on 17 June 1931 in National City, California. His parents, Antonio and Hedvig Baldessari, had met after arriving on the West Coast from Austria and Denmark. Baldessari’s father was a metal worker who salvaged and sold scrap, and his parents were largely self-sustaining, growing their own fruit and vegetables on land they owned, and tending to rabbits and chickens. The principles his parents instilled in him as a child meant he struggled to discard anything as an adult, instead deciding to appropriate and incorporate everyday objects into his art.

RELATED STORY

As a student, Baldessari majored in art education at San Diego State College, and was at first unsure as to whether to define himself as educator or artist. He taught art in junior high schools and community colleges before running an arts and crafts programme for the California Youth Authority, which included spending a summer attempting to reveal to a class of juvenile delinquents the joys of art – a job, he later said, was amply aided by his 6’7” frame.

In 1957, a studio class pushed Baldessari away from education and more towards introspective creation. By the time he visited the Duchamp retrospective in 1963, he had earned a spot studying at the prestigious Otis Art College of Art and Design in Los Angeles. Once ensconced in his CalArts post-studio, Baldessari became part of a movement of artists who placed more emphasis on the ideas an artwork expressed over aesthetic concerns regarding composition or draftsmanship. Yet, while other conceptualists in his sphere pursued their work with a pseudo-intellectual sincerity, Baldessari endeavoured always to seek out the fun in his work.

Wallpaper* Newsletter

Receive our daily digest of inspiration, escapism and design stories from around the world direct to your inbox.

A post shared by Alex Prager (@alexprager)

A photo posted by on

Alongside a fluency in Dadaism and frequent nods to the pop art practiced by New York artists like Andy Warhol and Roy Lichtenstein, Baldessari’s practice centred largely on doctoring and manipulating photographic ephemera taken images from news, stills from Hollywood movies, or advertising campaigns, many of which were bought for 10 cents apiece from a trinket store in Burbank, LA County. He would often obscure the faces visible in his found photographs, directing the viewer to focus on accidental elements of the composition. Baldessari would tell his students: ‘Don’t look at things — look in between things.’

Baldessari remained at CalArts, teaching and working in his post-studio, until 1988. From 1996 to 2005, he taught at the University of California, Los Angeles. His departure from university teaching coincided with a lifetime achievement award from the Americans for the Arts. He was elected to the American Academy of Arts and Letters in 2008; awarded a Golden Lion for Lifetime Achievement at the 2009 Venice Biennale; and received the National Medal of Arts from President Barack Obama in 2014. In the later chapters of his life, Baldessari became a world-famous art figure. From 2009 to 2011, a retrospective of his five-decade career, ‘Pure Beauty’, travelled to London’s Tate Modern, the Los Angeles County Museum of Art and MoMA in New York.

Baldessari’s death was confirmed on Sunday by Virginia Gatelein, his studio manager and foundation chairwoman. He is survived by his sister Betty Sokol, his daughter Annamarie, and his son Tony.

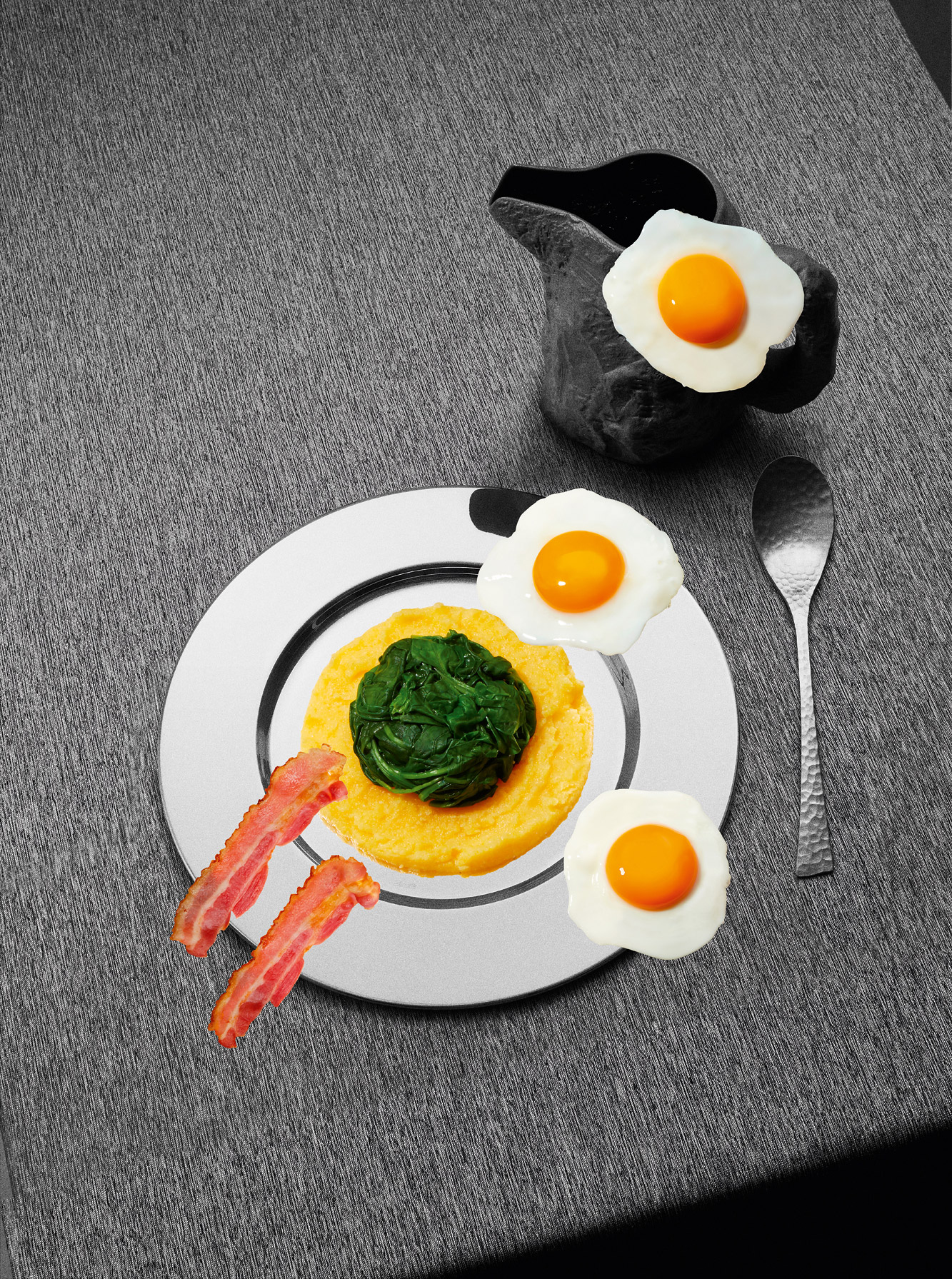

Baldessari’s polenta, spinach, eggs and bacon, as featured in the December 2016 issue of Wallpaper* (W*213). Upon seeing his recipe brought to life, the artist emailed with the comment, ‘Thank you, the presentation looks too good to eat.’

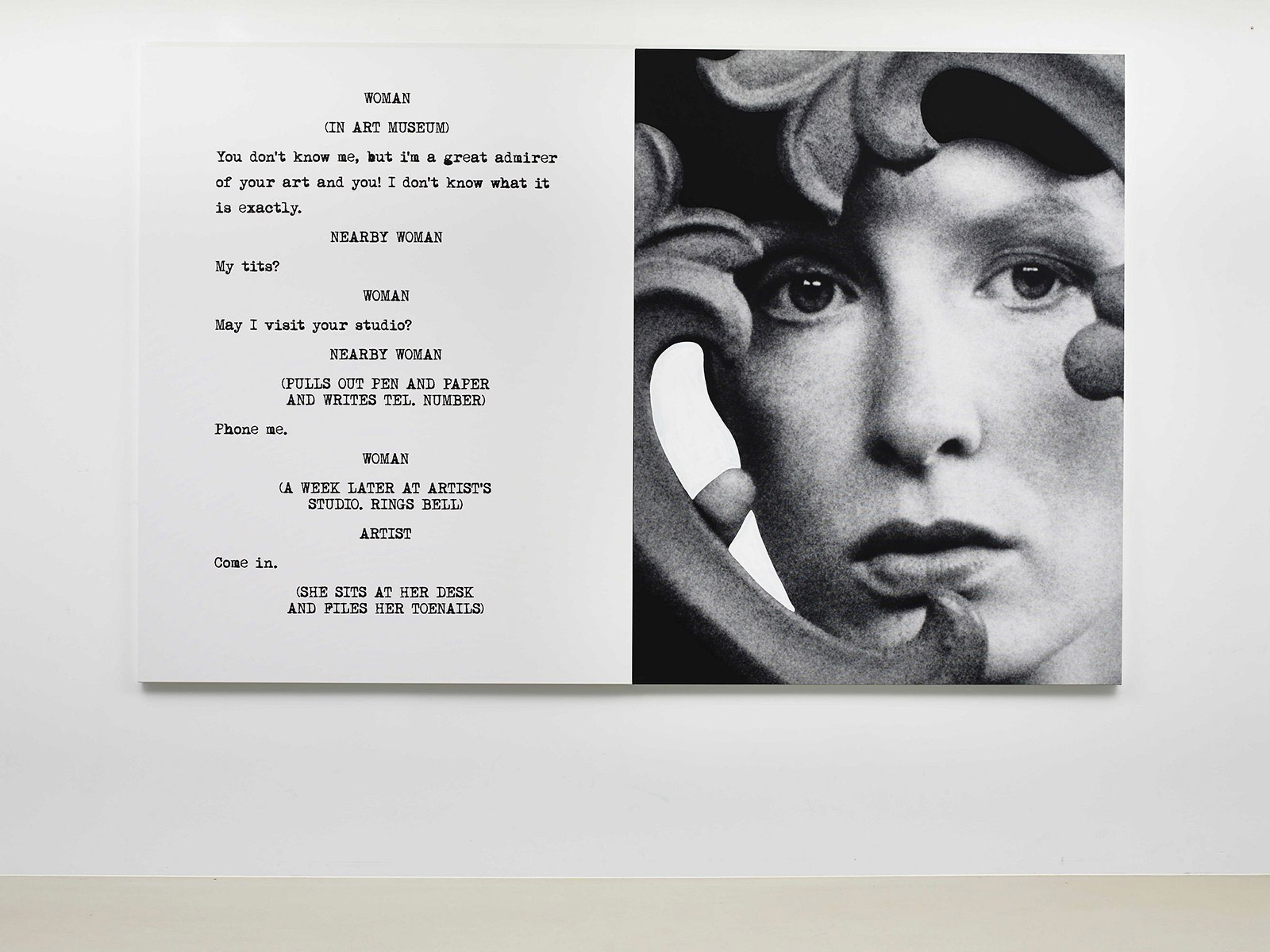

Pictures & Scripts: ...Files toenails., 2015, diptych; varnished inkjet print on canvas with acrylic paint. New York, Paris and London

Brain/Cloud: with Palm Tree and Seascape, 2009, polyurethane, paint, resin, aluminium, inkjet on vinyl. Courtesy of the artist and Marian Goodman Gallery New York, Paris and London

INFORMATION

mariangoodman.com; spruethmagers.com

Tom Seymour is an award-winning journalist, lecturer, strategist and curator. Before pursuing his freelance career, he was Senior Editor for CHANEL Arts & Culture. He has also worked at The Art Newspaper, University of the Arts London and the British Journal of Photography and i-D. He has published in print for The Guardian, The Observer, The New York Times, The Financial Times and Telegraph among others. He won Writer of the Year in 2020 and Specialist Writer of the Year in 2019 and 2021 at the PPA Awards for his work with The Royal Photographic Society. In 2017, Tom worked with Sian Davey to co-create Together, an amalgam of photography and writing which exhibited at London’s National Portrait Gallery.

-

Put these emerging artists on your radar

Put these emerging artists on your radarThis crop of six new talents is poised to shake up the art world. Get to know them now

By Tianna Williams

-

Dining at Pyrá feels like a Mediterranean kiss on both cheeks

Dining at Pyrá feels like a Mediterranean kiss on both cheeksDesigned by House of Dré, this Lonsdale Road addition dishes up an enticing fusion of Greek and Spanish cooking

By Sofia de la Cruz

-

Creased, crumpled: S/S 2025 menswear is about clothes that have ‘lived a life’

Creased, crumpled: S/S 2025 menswear is about clothes that have ‘lived a life’The S/S 2025 menswear collections see designers embrace the creased and the crumpled, conjuring a mood of laidback languor that ran through the season – captured here by photographer Steve Harnacke and stylist Nicola Neri for Wallpaper*

By Jack Moss

-

Leonard Baby's paintings reflect on his fundamentalist upbringing, a decade after he left the church

Leonard Baby's paintings reflect on his fundamentalist upbringing, a decade after he left the churchThe American artist considers depression and the suppressed queerness of his childhood in a series of intensely personal paintings, on show at Half Gallery, New York

By Orla Brennan

-

Desert X 2025 review: a new American dream grows in the Coachella Valley

Desert X 2025 review: a new American dream grows in the Coachella ValleyWill Jennings reports from the epic California art festival. Here are the highlights

By Will Jennings

-

In ‘The Last Showgirl’, nostalgia is a drug like any other

In ‘The Last Showgirl’, nostalgia is a drug like any otherGia Coppola takes us to Las Vegas after the party has ended in new film starring Pamela Anderson, The Last Showgirl

By Billie Walker

-

‘American Photography’: centuries-spanning show reveals timely truths

‘American Photography’: centuries-spanning show reveals timely truthsAt the Rijksmuseum in Amsterdam, Europe’s first major survey of American photography reveals the contradictions and complexities that have long defined this world superpower

By Daisy Woodward

-

Sundance Film Festival 2025: The films we can't wait to watch

Sundance Film Festival 2025: The films we can't wait to watchSundance Film Festival, which runs 23 January - 2 February, has long been considered a hub of cinematic innovation. These are the ones to watch from this year’s premieres

By Stefania Sarrubba

-

Remembering David Lynch (1946-2025), filmmaking master and creative dark horse

Remembering David Lynch (1946-2025), filmmaking master and creative dark horseDavid Lynch has died aged 78. Craig McLean pays tribute, recalling the cult filmmaker, his works, musings and myriad interests, from music-making to coffee entrepreneurship

By Craig McLean

-

What is RedNote? Inside the social media app drawing American users ahead of the US TikTok ban

What is RedNote? Inside the social media app drawing American users ahead of the US TikTok banDownloads of the Chinese-owned platform have spiked as US users look for an alternative to TikTok, which faces a ban on national security grounds. What is Rednote, and what are the implications of its ascent?

By Anna Solomon

-

Remembering Oliviero Toscani, fashion photographer and author of provocative Benetton campaigns

Remembering Oliviero Toscani, fashion photographer and author of provocative Benetton campaignsBest known for the controversial adverts he shot for the Italian fashion brand, former art director Oliviero Toscani has died, aged 82

By Anna Solomon