Fine figures: Jonathan Anderson and 6a celebrate fantastic forms at Hepworth Wakefield

In a bid to open itself up to alternative narratives and bring in new audiences, the UK’s Hepworth Wakefield is launching a series of shows curated by creative forces in other fields. The first opens this month. Entitled ‘Disobedient Bodies’, it is curated by Jonathan Anderson, the designer behind JW Anderson and creative director of Spanish leather goods house Loewe.

The Hepworth’s chief curator Andrew Bonacina hopes these alternative viewpoints will create fresh ways of navigating the collection. He chose Anderson as ‘he has often spoken about his love of Hepworth’s work and many other British artists, such as Henry Moore, Ben Nicholson, Lucie Rie and Hans Coper’. He adds, ’Jonathan has a very curatorial approach to bringing disparate things together in a way that’s expansive and promiscuous.’

Anderson, who had access to more than 5,000 works from the museum’s collection, homed in on Hepworth and Moore’s early works, at the point where they began to push the figurative towards abstraction. Anderson himself is interested in how abstraction may be read as a form of disobedience, whether in art, in his own fashion or that of other directional designers. According to Bonacina, ‘it’s about the confrontation of the form and where it goes’.

Installation view.

Anderson’s idea is to create a series of dialogues between works of art and fashion. The link is the human form in whatever way it’s represented. Think of pairings such as Naum Gabo’s Head No. 2 (1916), a loan from the Tate, and a Comme des Garçons A/W 2012 dress; Henry Moore’s Reclining Figure (1936) and a Jean Paul Gaultier conical-bust dress from 1984; and Dorothea Tanning’s Nue couchée (1969–70), also from the Tate, and JW Anderson jumpers from S/S 2017. ‘Culturally, we grade things: on fame, how good they are or on price,’ says Anderson. Such pairings aim to dissolve aesthetic hierarchies by presenting art alongside fashion and photography.

‘Disobedient Bodies’ also features Jean Arp’s S’élevant (1962); Constantin Brâncuşi’s Prometheus (1912); Louise Bourgeois’ Echo VIII (2007); and Alberto Giacometti’s Standing Woman (1958), sourced from private galleries and public collections, including the Sainsbury Centre for Visual Arts, the Scottish National Gallery of Modern Art, and Anderson’s ‘favourite place on the planet’, Kettle’s Yard at the University of Cambridge.

’Grace’, by Sarah Lucas, 2006.

For Anderson, ‘fashion is about the body, and art is about an emotional interpretation of the body’. For the show, he has chosen work by designers such as Helmut Lang, Issey Miyake and Rei Kawakubo, as they are, in his opinion, ‘the most influential in terms of how they changed form’. Another pick is a Ligne Profilée dress from Christian Dior’s 1952 collection, with its padded hips; Anderson says it’s ‘just like art’, sitting off the front of the body, like ‘a 3D building’.

The show is installed across four of the temporary exhibition galleries. The first room is a giant scrapbook of stories and narratives, or a kaleidoscope of influences, a mass of imagery which traces the form of the body through art, design, fashion and photography. Bonacina believes the studio-style display will help establish the narrative of the exhibition, creating a coherent dialogue out of unexpected objects. Think of it as a giant moodboard, anchored by Moore and Hepworth. Anderson hopes this will let visitors understand his own design process, as he builds a collection, drawing out a thread to get to an end point. He doesn’t see himself as a fashion designer, as he is not classically trained. Instead, he is constantly researching, be it at a flea market, on the internet or on Instagram. He collects countless visuals and ideas and mixes them; his original creative direction is how these are edited and used.

Wallpaper* Newsletter

Receive our daily digest of inspiration, escapism and design stories from around the world direct to your inbox.

The exhibition installation has been conceived with Stephanie Macdonald and Tom Emerson of London’s 6a Architects, whose projects include the extension to the South London Gallery; Raven Row, an art gallery in Spitalfields; the façade of Paul Smith’s Albermarle Street store; and Juergen Teller’s studio in west London.

’Head No. 2’ (enlarged version), by Naum Gabo, 1964., London 2016. © Nina & Graham Williams

To understand the concept behind the installation in the two principal galleries, Macdonald and Emerson suggest imagining ‘a cocktail party where people are thrown together, paired up slightly uncomfortably, and forced to make small talk with people they don’t know’. The conversations are organised and divided by fabric curtains hung in a grid, with slow variations of colour giving private space to each conversation, yet allowing a glimpse of the next ‘conversation’. Here among the art and fashion there are chairs such as Gerrit Rietveld’s ‘Zig-Zig’ and Eileen Gray’s ‘Non-Conformist’. As Emerson puts it, ‘if there is one object that specifically talks to the body, it’s a chair’.

The fourth gallery, at the heart of the exhibition, is devoted to knits. According to Tom Emerson, this space will become an interactive forest of ‘super jumpers’, all especially commissioned, supersize versions of the elongated sweaters shown in Anderson’s S/S 2017 men’s catwalk show.

Anderson’s starting point for the exhibition was Henry Moore’s Reclining Figure (1936), paired with 2015 photographs by collaborator Jamie Hawkesworth, in which models were fully covered in knitted sheaths from the JW Anderson line, the body turned into sculptural forms. Suspended from the ceiling, some of these sweaters will be 8m long. The idea is for visitors to wear them and become sculptures themselves. For the Instagram generation, this is the selfie room, where you may end up resembling a reclining Moore or Isamu Noguchi’s 1951 ‘E’ lamp shown in the other gallery.

Anderson wanted to address the distance between exhibit and visitor in the gallery context. Barbara Hepworth always said her work needed to be touched, although that’s not currently permitted in today’s conservation-conscious art world. Each night the Hepworth produces a daily ‘touch list’ of visitors who disobey the rules: now the disobedient become part of the show.

As originally featured in the March 2017 issue of Wallpaper* (W*216)

An installation view of the Comme Des Garcons felt 2D collection, 2012.

Jean Arp’s marble sculpture pictured alongside a Dior Patchoul dress.

Image from The Thinleys, Anderson’s fanzine and M/M (Paris), 2015. © Jamie Hawkesworth

’Conversations’ are divided and organised by fabric curtains, giving privacy between each room yet allowing a glimpse of the next space.

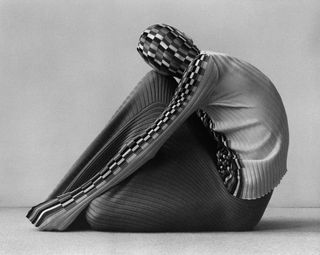

Moodboard: Anderson’s inspirations for the exhibition. Pictured, Crinoline by Yohji Yamamoto, A/W95

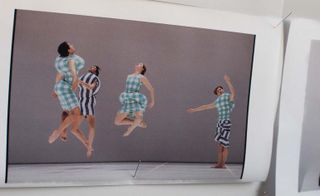

Dancers in Rei Kawakubo’s costumes for Merce Cunningham’s 1997 ballet, Scenario.

Reclining Figure, by Henry Moore, 1936. Courtesy of The Hepworth Wakefield

Detail of the moodboards prepared for the show in Anderson’s office

An installation view of ’28 Jumpers’, by JW Anderson.

‘Patchouli’ dress, by Christian Dior, AW52.

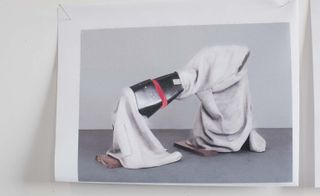

Clothes being assembled for the exhibition, including an elongated polo-neck jumper by JW Anderson and an Issey Miyake dress

Love, by Siobhán Hapaska, 2016. , Dublin

The pieces on show include sculptures by Henry Moore, Sarah Lucas and Barbara Hepworth.

INFORMATION

‘Disobedient Bodies’ is on view until 18 June. For more information, visit the Hepworth Wakefield website

ADDRESS

Hepworth Wakefield

Gallery Walk

Wakefield WF1 5AW

Also known as Picky Nicky, Nick Vinson has contributed to Wallpaper* Magazine for the past 21 years. He runs Vinson&Co, a London-based bureau specialising in creative direction and interiors for the luxury goods industry. As both an expert and fan of Made in Italy, he divides his time between London and Florence and has decades of experience in the industry as a critic, curator and editor.

-

‘Splash! A Century of Swimming and Style’ at Design Museum interrogates the loaded history of swimwear

‘Splash! A Century of Swimming and Style’ at Design Museum interrogates the loaded history of swimwearCurator Amber Butchart speaks to Wallpaper* about the Design Museum’s latest exhibition, which explores the cultural impact of swimwear – from Pamela Anderson’s bombshell ‘Baywatch’ one-piece to those made for sports, leisure or fashion statement

By Zoe Whitfield Published

-

The Frick Collection's expansion by Selldorf Architects is both surgical and delicate

The Frick Collection's expansion by Selldorf Architects is both surgical and delicateThe New York cultural institution gets a $220 million glow-up

By Stephanie Murg Published

-

Come as you are to see Kurt Cobain’s acoustic guitar on show in the UK for the first time

Come as you are to see Kurt Cobain’s acoustic guitar on show in the UK for the first timeKurt Cobain’s acoustic guitar goes on display at the Royal College of Music Museum in London as part of an exhibition exploring Nirvana’s MTV Unplugged performance

By Tianna Williams Published

-

Out of office: what the Wallpaper* editors have been doing this week

Out of office: what the Wallpaper* editors have been doing this weekA trip to Geneva, a festive light ceremony, new season fashion and pre party season health and wellness: it's been another busy week in the world of Wallpaper*

By Bill Prince Published

-

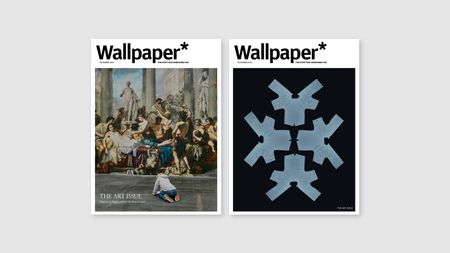

Discover Wallpaper* November 2024: The Art Issue

Discover Wallpaper* November 2024: The Art IssueThe art special is on sale now. Confront the classical canon with Elmgreen & Dragset, get down with LoveFrom x Moncler, and wear art on your sleeve with Christiane Kubrick x JW Anderson

By Bill Prince Published

-

Loewe marks 100 years of the Surrealist Manifesto in Madrid

Loewe marks 100 years of the Surrealist Manifesto in MadridLoewe Foundation presents 'Surrealist Centennial' at the Leica Gallery, Madrid

By Hannah Silver Published

-

The Loewe Foundation Craft Prize 2024 winner is Mexican ceramic artist Andrés Anza

The Loewe Foundation Craft Prize 2024 winner is Mexican ceramic artist Andrés AnzaAs the winner of the Loewe Foundation Craft Prize 2024 is announced at Paris’ Palais de Tokyo this evening (14 May 2024), Loewe creative director Jonathan Anderson talks to Wallpaper* about the continuing importance of the prize as an ’incubator of individuals’

By Jack Moss Published

-

Edinburgh Art Festival 2023: from bog dancing to binge drinking

Edinburgh Art Festival 2023: from bog dancing to binge drinkingWhat to see at Edinburgh Art Festival 2023, championing women and queer artists, whether exploring Scottish bogland on film or casting hedonism in ceramic

By Amah-Rose Abrams Published

-

Last chance to see: Devon Turnbull’s ‘HiFi Listening Room Dream No. 1’ at Lisson Gallery, London

Last chance to see: Devon Turnbull’s ‘HiFi Listening Room Dream No. 1’ at Lisson Gallery, LondonDevon Turnbull/OJAS’ handmade sound system matches minimalist aesthetics with a profound audiophonic experience – he tells us more

By Jorinde Croese Published

-

Hospital Rooms and Hauser & Wirth unite for a sensorial London exhibition and auction

Hospital Rooms and Hauser & Wirth unite for a sensorial London exhibition and auctionHospital Rooms and Hauser & Wirth are working together to raise money for arts and mental health charities

By Hannah Silver Published

-

‘These Americans’: Will Vogt documents the USA’s rich at play

‘These Americans’: Will Vogt documents the USA’s rich at playWill Vogt’s photo book ‘These Americans’ is a deep dive into a world of privilege and excess, spanning 1969 to 1996

By Sophie Gladstone Published