Conversation piece: Hans Josephsohn and Peter Märkli meet at Hauser & Wirth

In the early autumn sunlight, the Piet Oudolf-designed garden at Hauser & Wirth in Somerset looks ephemeral with the deep browns and purples of the fauna muted by the cold. The air feels fresh and the complex of barns, with contemporary colonnaded additions by Laplace, casts soft shadows across the courtyard pathways.

It was also in autumn, 20 years ago, that Niall Hobhouse nonchalantly acquired a key from a local restaurant in the small village of Giornico in Switzerland, which opened the door to La Congiunta, a gallery hidden in the alpine countryside designed by Swiss architect Peter Märkli.

Built in 1992, La Congiunta was commissioned by artist Hans Josephsohn as a permanent home to around 30 of his sculptures. The concrete form commands a graceful aura of mystic in the landscape, appearing in shape and presence almost like a mausoleum.

It was the physical marker of this partnership, between artist and architect, that so transfixed Hobhouse on that visit, and compelled him to eventually curate the exhibition ‘Josephsohn / Märkli: A Conjunction’ at Hauser & Wirth.

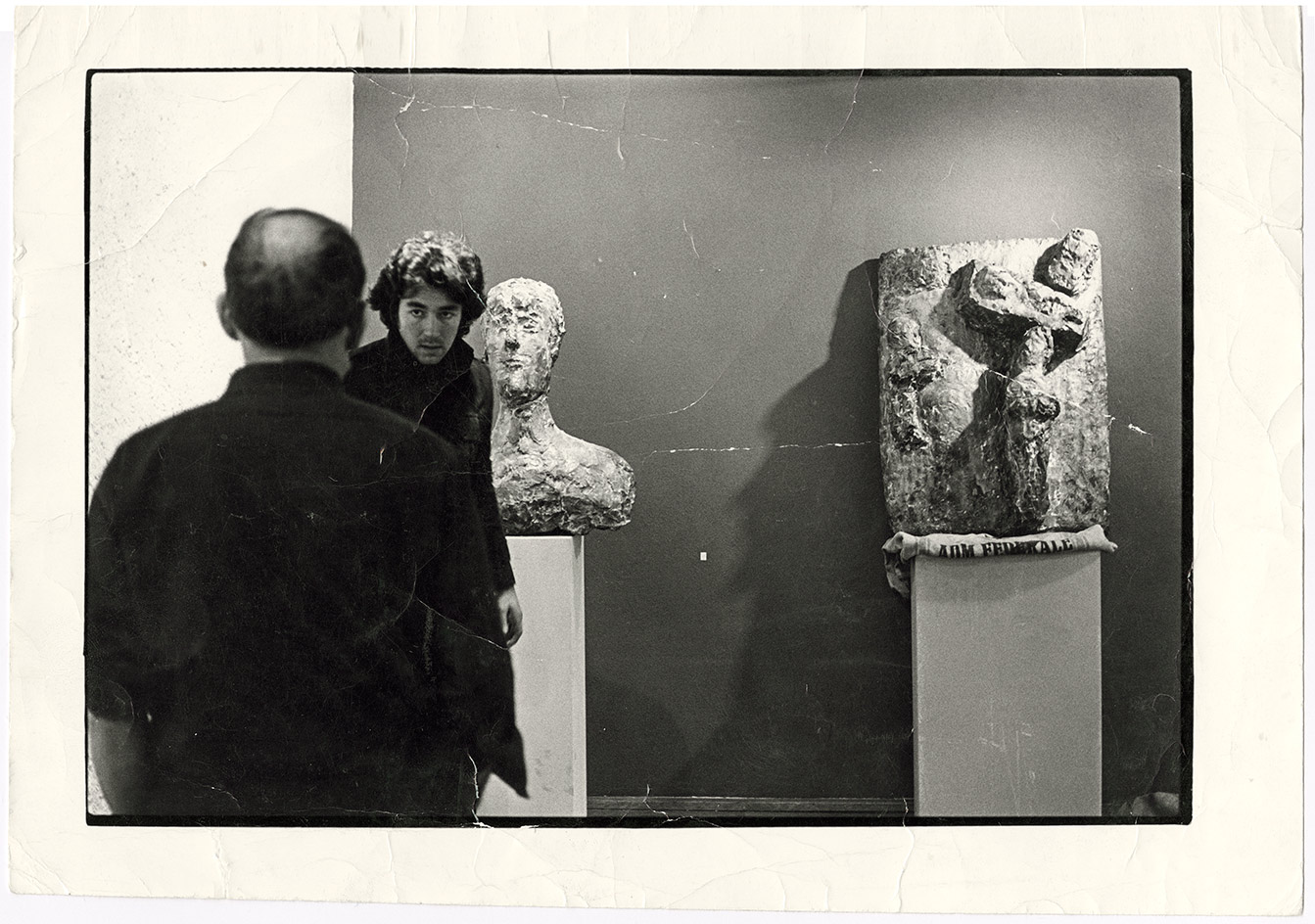

Exhibition installation at Galerie an der Stadthausgasse Schaffhausen, 20.2.1978.

Placing works side by side was an effort to trace a material narrative – to find bridges and pathways meandering through studies, drawings and sketchbooks – that might just lead to an evolved understanding of of Josephsohn and Märkli’s complex relationship. It's a friendship eternalised by La Congiunta, where isolated in the countryside, no matter what season, their work is in permanent conversation.

Instead of in Zurich, where Märkli studied architecture at ETHZ and began to visit Josephsohn in his studio, the exhibition makes material sense in Somerset, where gallery spaces converted from former barns bring an additional interpretation to the work – similarly to how viewing Josephsohn’s works at such a specific location such as La Congiunta might.

Hobhouse worked hard with Ulrich Meinherz of the Josephsohn Estate to present Josephsohn’s works in a new way. The walls of the ‘Thrashing Barn’, where the exhibition begins, bring a sandy backdrop to Josephson’s roughly moulded brass sculptures, while a huge floor to ceiling window overlooking a green lawn frames a medium-scale, bronze torso on a plinth.

Modelled from life models in plaster and then cast in brass, Josephsohn’s sculptures are like uncovered archaeological finds – his process, which he modified yet stayed loyal to for most of his career, generated an artificial historical weight through the worked surfaces that slowly developed a dull golden patina.

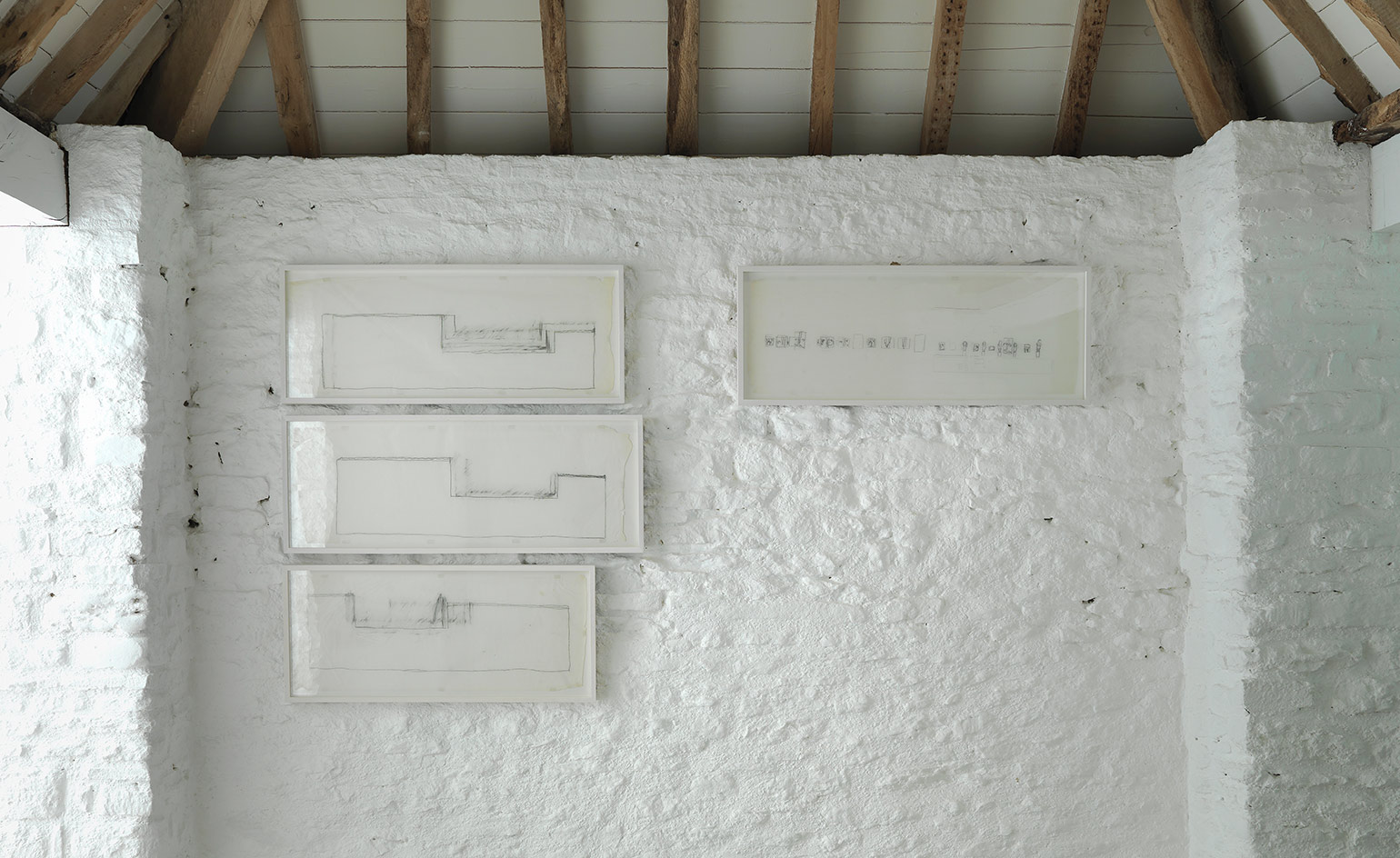

In the next room, where white walls meet the structural wooden beams of the barn, Markli’s drawings made in pen or pencil, and sometimes soft coloured crayon, on paper - frame compositions of single family homes, repeated in their frames with minor adjustments. While these are not technical drawings, or even designs for any commission at all, there is something systematic about the repetition of shapes and forms, like hieroglyphs. They oppose Josephsohn’s smaller scale wall works that are also rectangular in shape and appear like weathered religious icons.

Jospehsohn's relief works in brass, on view at Hasuer & Wirth Somerset

This physical, process-led opposition was part of the beginning of Hobhouse’s curation of the exhibition: ‘In choosing this very compressed format of the small reliefs and the what Peter calls “language drawings”, both he and Josphsohn started by asking, “what is this very narrow enquiry and why make it so narrow in terms of what you’re trying to produce?”’

As well as a narrow conceptual enquiry, both sculptor and architect show a strict sense of confinement through strong lines in their work. The reliefs and the language drawings show an intense need for limitation and shelter – which is an intimately human experience connected to an awareness of space and death, while travelling an open-ended journey through life, time and nature.

‘I’ve worked with Peter for years and always wondered what the relationship is between his language drawings and the built work,’ says Hobhouse. ‘For me, there are clues; the houses are largely without scale and context and seem to be about trying to explore human scale in architecture. All of this preoccupation with this very simple house facade – which at times gets very elaborate and then very simplified – ends with building La Congiunta. Suddenly – and you see this in the last room – all this effort becomes completely abstract and cultural and all the questions about scale disappear inside the building.’

In the centre of the third room of the exhibition –the ‘Pigsty’ – two reclining sculptures at different scales sit on plinths. One of them is a first cut of a La Congiunta sculpture, bringing a sense of mass and scale experienced within the Swiss gallery. While Märkli’s drawings of La Congiunta on the walls show how its architectural form directly speaks to the sculptures – so sensitive to the height and weight, that the walls almost hug their forms.

For Hobhouse, Märkli’s sketchbooks – which he found in a drawer in Märkli’s Zurich studio, where the architect had granted him free reign for a day – provided the ‘missing bridge’ between the language drawings and the buildings. Displayed in vitrines, there is a circularity to the beginning of the exhibition where we see Josephsohn’s line drawings in vitrines, a conscious choice by Hobhouse: ‘These drawings were never intended for people to see – they were either for reference or speculation – but they were only for Josephsohn and Märkli to see.’

On view in a separate education room in a different barn, two of Märkli’s sketchbooks seen in the exhibition have been digitized so the viewer can flick through the pages to see the forms developing like a language. Here, books and videos, as well as an accompanying publication reveal further insight into the work and processes of the Josephsohn and Märkli. Hobhouse wanted the exhibition itself to be all about material, where he is ‘trusting the audience to use their eyes’ to uncover the relationships between Josephsohn and Märkli.

The first room of the exhibition opens with an arrangement of Josephsohn’s free-standing sculptures and wall-based reliefs in brass

The second room of the exhibition presents reliefs by Josephsohn and drawings by Märkli in opposition

A line of Märkli's ‘language drawings’

Josephsohn’s small wall based reliefs presented on the stone work of Hauser & Wirth Somerset’s converted barn gallery

Josephsohn and Märkli’s works in conversation in the exhibition

Reliefs by Josephsohn and drawings by Märkli side by side

Märkli’s drawings of La Conguinta in Switzerland

Installation view of ‘Josephsohn / Märkli. A Conjunction’ at Hauser & Wirth Somerset

The reclining sculpture by Josephsohn in the third room of the exhibition

Hans Josephsohn (1920 - 2012) Untitled 1962-1964 Left: Untitled, 1962-4, Brass. St. Gallen. Courtesy of Josephsohn Estate, Kesselhaus Josephsohn/Galerie Felix Lehner, St Gallen, Hauser & Wirth. Right: Peter Märkli, Drawings of Facade Studies, 1980-1999 Pencil, coloured pencil and pen on paper. Courtesy of the artist and Betts Project

INFORMATION

‘Josephsohn / Märkli: A Conjunction’ is on view until 1 January 2018. For more information, see the Hauser & Wirth website

Receive our daily digest of inspiration, escapism and design stories from around the world direct to your inbox.

Harriet Thorpe is a writer, journalist and editor covering architecture, design and culture, with particular interest in sustainability, 20th-century architecture and community. After studying History of Art at the School of Oriental and African Studies (SOAS) and Journalism at City University in London, she developed her interest in architecture working at Wallpaper* magazine and today contributes to Wallpaper*, The World of Interiors and Icon magazine, amongst other titles. She is author of The Sustainable City (2022, Hoxton Mini Press), a book about sustainable architecture in London, and the Modern Cambridge Map (2023, Blue Crow Media), a map of 20th-century architecture in Cambridge, the city where she grew up.

-

The Testament of Ann Lee brings the Shaker aesthetic to the big screen

The Testament of Ann Lee brings the Shaker aesthetic to the big screenDirected by Mona Fastvold and featuring Amanda Seyfried, The Testament of Ann Lee is a visual deep dive into Shaker culture

-

Dive into Buccellati's rich artistic heritage in Shanghai

Dive into Buccellati's rich artistic heritage in Shanghai'The Prince of Goldsmiths: Buccellati Rediscovering the Classics' exhibition takes visitors on an immersive journey through a fascinating history

-

Love jewellery? Now you can book a holiday to source rare gemstones

Love jewellery? Now you can book a holiday to source rare gemstonesHardy & Diamond, Gemstone Journeys debuts in Sri Lanka in April 2026, granting travellers access to the island’s artisanal gemstone mines, as well as the opportunity to source their perfect stone

-

Inside architect Andrés Liesch's modernist home, influenced by Frank Lloyd Wright

Inside architect Andrés Liesch's modernist home, influenced by Frank Lloyd WrightAndrés Liesch's fascination with an American modernist master played a crucial role in the development of the little-known Swiss architect's geometrically sophisticated portfolio

-

A building kind of like a ‘mille-feuille’: inside Herzog & de Meuron’s home for Lombard Odier

A building kind of like a ‘mille-feuille’: inside Herzog & de Meuron’s home for Lombard OdierWe toured ‘One Roof’ by Herzog & de Meuron, exploring the Swiss studio’s bright, sustainable and carefully layered workspace design; welcome to private bank Lombard Odier’s new headquarters

-

Audrey Hepburn’s stunning Swiss country home could be yours

Audrey Hepburn’s stunning Swiss country home could be yoursAudrey Hepburn’s La Paisable house in the tranquil village of Tolochenaz is for sale

-

Meet Lisbeth Sachs, the lesser known Swiss modernist architect

Meet Lisbeth Sachs, the lesser known Swiss modernist architectPioneering Lisbeth Sachs is the Swiss architect behind the inspiration for creative collective Annexe’s reimagining of the Swiss pavilion for the Venice Architecture Biennale 2025

-

A contemporary Swiss chalet combines tradition and modernity, all with a breathtaking view

A contemporary Swiss chalet combines tradition and modernity, all with a breathtaking viewA modern take on the classic chalet in Switzerland, designed by Montalba Architects, mixes local craft with classic midcentury pieces in a refined design inside and out

-

Herzog & de Meuron’s Children’s Hospital in Zurich is a ‘miniature city’

Herzog & de Meuron’s Children’s Hospital in Zurich is a ‘miniature city’Herzog & de Meuron’s Children’s Hospital in Zurich aims to offer a case study in forward-thinking, contemporary architecture for healthcare

-

Step inside La Tulipe, a flower-shaped brutalist beauty by Jack Vicajee Bertoli in Geneva

Step inside La Tulipe, a flower-shaped brutalist beauty by Jack Vicajee Bertoli in GenevaSprouting from the ground, nicknamed La Tulipe, the Fondation Pour Recherches Médicales building by Jack Vicajee Bertoli is undergoing a two-phase renovation, under the guidance of Geneva architects Meier + Associé

-

Christian de Portzamparc’s Dior Geneva flagship store dazzles and flows

Christian de Portzamparc’s Dior Geneva flagship store dazzles and flowsDior’s Geneva flagship by French architect Christian de Portzamparc has a brand new, wavy façade that references the fashion designer's original processes using curves, cuts and light