‘I just didn’t fit’: feminist icon Judy Chicago on revolutionising art history

At the de Young Museum, San Francisco, American feminist artist Judy Chicago staged her first ever retrospective. We spoke to the artist about her epic career, filled with patriarchal battles, fierce self-belief, and a lot of smoke

At the age of 82, and after 60 years of spearheading feminist art, Judy Chicago has just received her first retrospective. Puzzling, perhaps, that it’s taken so long, but in understanding Chicago’s relatively recent institutional acclaim, one must first appreciate what it took to arrive here.

I reach Chicago via Zoom. She’s in a San Francisco hotel preparing a new Smoke Sculpture to accompany her seminal show at the city’s de Young Museum. She sits on a chair, knees bent to her chest; her wavy hair has psychedelic purple sides with a silver top. She’s eating breakfast, then apologising for eating breakfast. ‘So tell me about you,’ she begins. Not a question a journalist often predicts, but then predictability is not exactly synonymous with Judy Chicago.

Installation view of 'Judy Chicago: A Retrospective' at the de Young Museum. Image provided courtesy of the Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco

Chicago was born Judith Cohen in Illinois in 1939 to a family of Jewish liberals. Her mother, a dancer, nurtured her prodigious creative flair; her father, a Marxist and labour organiser, doted on Chicago and instilled in her a political consciousness and passion for social justice. In childhood, her parents armed her with a fierce self-belief. She never considered that, as a woman, her aspirations would be unobtainable; these were obstacles reserved for adulthood.

The veneer began to abrade when Chicago was studying at UCLA. In response to an environment riddled with hostility and cultural contempt for female creativity, the artist adopted ‘macho’ materials and techniques, like automotive parts and heavy machinery. ‘My gender kept slipping into my work,’ says Chicago. ‘I either had to try to construct an alternative face for myself and other women, or continue to not be taken seriously.’

The patriarchy was urging Chicago to make a choice: be a woman, or be an artist. But she wanted to be both. ‘I watched my male artist colleagues moving along the choo-choo train of success, then I showed work like Rainbow Pickett (1965), and nothing happened. I felt like even though I was trying my best to be one of the guys, it wasn’t working, so I thought, “What do I have to lose by being myself?”’

Installation view of 'Judy Chicago: A Retrospective' at the de Young Museum. Image provided courtesy of the Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco

In 1970, Judy Gerowitz – then her married name – legally became Judy Chicago to ‘divest herself of all names imposed upon her through male dominance’. The same year, she founded the first feminist art education programme in the US at California State University, Fresno, but there remained little discourse on the lack of female representation in art. ‘Other women artists were working then, two from the Bay Area, Joan Brown and Jay DeFeo. I tried to raise the issue and asked what it was like for them, and they wouldn’t talk about it, they denied it. It was a level of fear combined with lack of consciousness.’

In 1979, Chicago unleashed a tidal wave on the art world with The Dinner Party. The installation was visited by 100,000 people in its first three months and would be seen by 15 million by 1996. It was audacious, unabashedly vaginal, staggering in scale and content, and unprecedented in its celebration of ‘feminine’ craft. The piece is formed of a triangular table with 39 elaborate place settings for 39 iconic women from myth and history, including Sojourner Truth, Georgia O’Keeffe and Virginia Woolf. ‘Even though I believed in myself, it wasn’t an easy road that I trod. If I had not found my history as a woman, and learned about what all those women before me had faced and overcome, I could never have done it,’ she says.

Installation view of 'Judy Chicago: A Retrospective' at the de Young Museum. Image provided courtesy of the Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco

But another tidal wave loomed, one carrying an unexpected concoction of criticism and utter annihilation – ‘a lumbering mishmash of sleaze and cheese’, said one Los Angeles Times critic of her installation.

Criticism came from other, more unexpected sources. ‘When The Dinner Party opened, there was a group of English feminists who were like, “Monuments are male”. I was like, “Excuse me? Why do guys only get to do the monumental?”’ Chicago recalls.

A gulf formed between those who revered Chicago’s work, and those who mauled it, but there were also those who ignored it altogether. ‘I just didn’t fit,’ says Chicago. ‘I was marginalised for many decades because nobody could fit me into the narrow categories of contemporary art. When I was young, I wanted to fit in, but now I’m old I'm like, “I don’t want to fit in.”’

When I was young, I wanted to fit in, but now I’m old I'm like,I don’t want to fit in

Forty years after The Dinner Party was exhibited at the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, Chicago’s de Young retrospective feels like a homecoming of sorts. Its 130 paintings, prints, drawings, and ceramic sculptures, alongside ephemera and several films chart her bold and brilliant path. ‘Claudia Schmuckli [Chicago’s de Young exhibition curator] is probably the first person to try to represent my art practice and make it intelligible across different subjects and techniques. When we came here [to San Francisco], I said to her, “I have no idea how I’m going to react when I see my entire life’s work presented. I could just end up in tears on the floor.”’

RELATED STORY

Chicago is also well known for her Smoke Sculptures – also known as Atmospheres – which she began in the 1960s. In these cinematic works, pigments flood the air, liberating colour from the rigidity of painting and sculpture. ‘It was an effort to feminise and soften an exceedingly male-centred art scene,’ she says. While her male contemporaries – the likes of Michael Heizer, James Turrell and Robert Smithson – were busy moving the earth with their land art, Chicago’s Atmospheres were a different sort of environmental intervention: explosive, ephemeral and, contrary to the work of her peers, left little trace.

Judy Chicago, Immolation, from the series Women and Smoke, 1972. Fireworks performance; performed in California desert. Courtesy of the artist; Salon 94, New York; and Jessica Silverman, San Francisco. © Judy Chicago / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York. Photograph courtesy of Through the Flower Archives. Image provided courtesy of the Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco

Her first wave of Atmospheres was created between 1968 and 1974. ‘When I started, the issue of toxicity and the effect on the environment wasn’t even in people’s consciousness.’ Chicago stopped making Smoke Sculptures until 2011. ‘By then, they were formulated using environmentally riendly, non-toxic materials; basically, just pigment which washes away.’

These days, Chicago’s adventures in pyrotechnics are no less dramatic. In July 2021 Diamonds in the Sky was showcased in Belen, the New Mexico town where she lives in a former hotel with her photographer husband Donald Woodman. ‘Some woman called the office and said, “The smoke turned my hair yellow.”’ Chicago’s studio manager, aware of the soluble properties of the smoke’s residue, replied, ‘Did you try washing your hair?’ The woman had not. More recently, during the creation of Niçoise Smoke, a mini Smoke Sculpture that Chicago produced for Wallpaper’s Artist’s Palate series, a concerned witness raised the alarm. ‘We had no idea how much smoke we’d need. In the first one, there was way too much smoke, and it completely covered everything and the fire department came,’ said Chicago. On 16 October 2021, a new, 15-minute long Smoke Sculpture, Forever de Young will be performed in front of the museum in celebration of ‘Judy Chicago: A Retrospective’.

Chicago – whose new autobiography, The Flowering, was published earlier this year – has had a career punctuated by interventions. It all began with injecting expression into the emotion-deprived landscape of 1960s minimalism and reached acclaim, and notoriety, with The Dinner Party, a work that shook the foundations of art history. But the work Chicago has created since has been no less prophetic, fearless or radical; it continues to expose the untold facets of history, and penetrate contemporary culture deeper than most will dare to.

Wallpaper* Newsletter

Receive our daily digest of inspiration, escapism and design stories from around the world direct to your inbox.

Rainbow Shabbat, 1992, Judy Chicago and Donald Woodman. Installation view of 'Judy Chicago: A Retrospective' at the de Young Museum

From 1985 to 1993, Chicago collaborated with Woodman on The Holocaust Project: From Darkness into Light. They delved into their Jewish roots while confronting global power structures. By examining the Holocaust in a contemporary context, the piece became a prism through which to explore oppression, injustice, and the darkest caverns of human cruelty, but also hope.

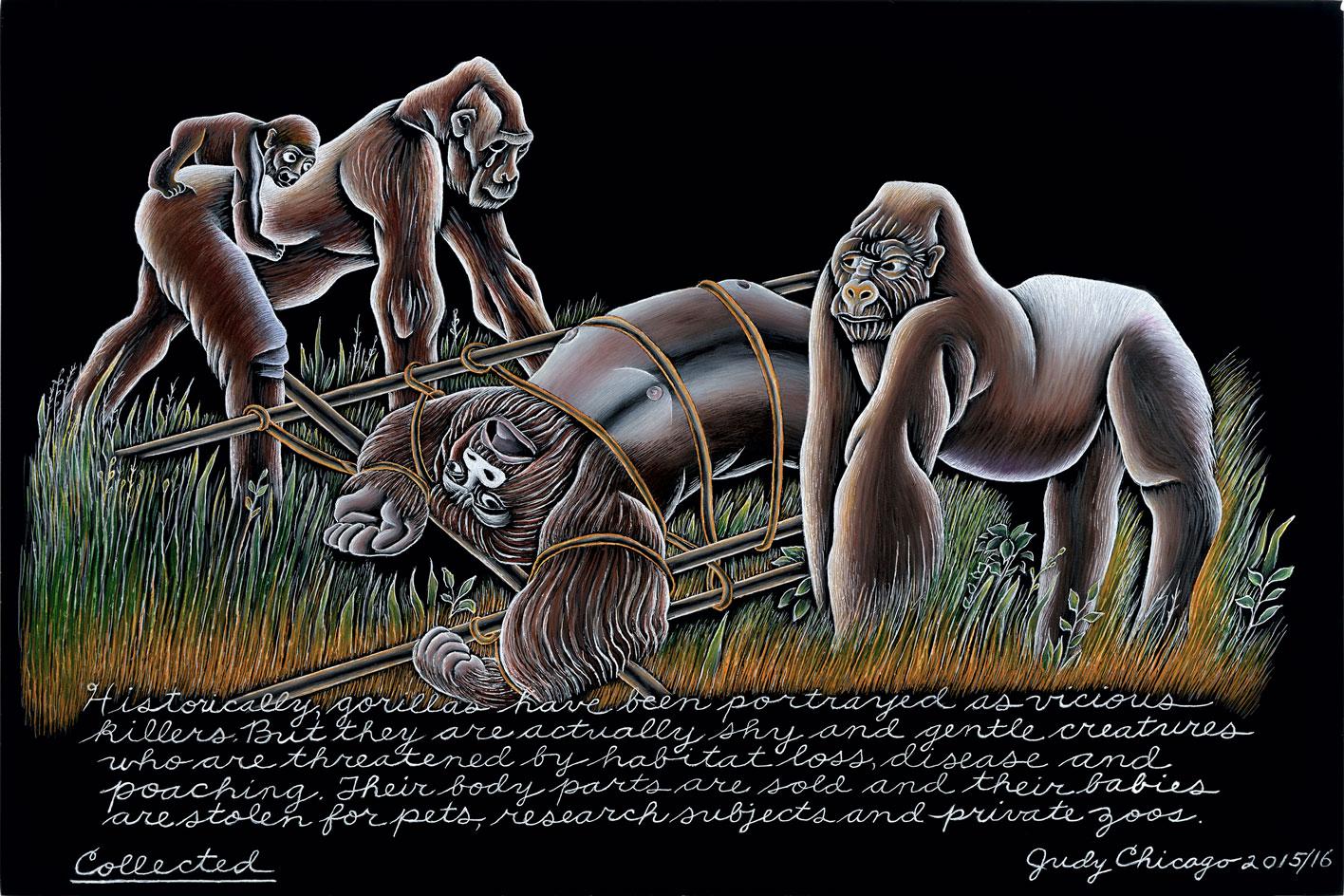

Her most recent body of work, The End: A Meditation on Death and Extinction (2015 – 2019), casts a searing eye on her own mortality, and the extinction of other species through human action, and inaction. ‘In a lot of environmental [art]work, suffering is aestheticised. You see extinct animals but don’t see how they became extinct,’ she says. ‘It’s not comfortable to look at my work, but I don’t think art’s function is to make you comfortable. I think art’s function is to make you think.’

Judy Chicago, Collected, from The End: A Meditation on Death and Extinction, 2015. © Judy Chicago/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York.

Now that the art world has acclimatised to works like The Dinner Party, Chicago’s new show will take things up a gear. ‘Claudia has installed my retrospective backwards,’ explains Chicago. ‘You see the most uncomfortable work before you reach the comfortable work.’

Chicago’s art has never been easy to digest, and that’s the whole point. But it erupts from a place of deep curiosity, intellect, determination, wisdom and above all, empathy, not just with female artists, but with all those marginalised by the patriarchy.

When Chicago first blazed a trail for the feminist art movement, the world wasn’t ready. But it’s not as though Judy Chicago’s art is finally in tune with the times; the times have finally caught up with Judy Chicago.

FAMSF hosts Judy Chicago's Forever de Young Smoke Sculpture on 16 October 2021 at de Young Museum in San Francisco,CA

FAMSF hosts Judy Chicago's Forever de Young Smoke Sculpture on 16 October 2021 at de Young Museum in San Francisco, CA

FAMSF hosts Judy Chicago's Forever de Young Smoke Sculpture on 16 October 2021 at de Young Museum in San Francisco, CA

INFORMATION

‘Judy Chicago: A Retrospective’, until 9 January 2021, de Young Museum, deyoung.famsf.org

The Flowering: The Autobiography of Judy Chicago, with introduction by Gloria Steinem, is published by Thames & Hudson, thamesandhudsonusa.com

ADDRESS

De Young Museum

Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco

50 Hagiwara Tea Garden Dr

San Francisco, CA 94118

Harriet Lloyd-Smith was the Arts Editor of Wallpaper*, responsible for the art pages across digital and print, including profiles, exhibition reviews, and contemporary art collaborations. She started at Wallpaper* in 2017 and has written for leading contemporary art publications, auction houses and arts charities, and lectured on review writing and art journalism. When she’s not writing about art, she’s making her own.

-

Put these emerging artists on your radar

Put these emerging artists on your radarThis crop of six new talents is poised to shake up the art world. Get to know them now

By Tianna Williams

-

Dining at Pyrá feels like a Mediterranean kiss on both cheeks

Dining at Pyrá feels like a Mediterranean kiss on both cheeksDesigned by House of Dré, this Lonsdale Road addition dishes up an enticing fusion of Greek and Spanish cooking

By Sofia de la Cruz

-

Creased, crumpled: S/S 2025 menswear is about clothes that have ‘lived a life’

Creased, crumpled: S/S 2025 menswear is about clothes that have ‘lived a life’The S/S 2025 menswear collections see designers embrace the creased and the crumpled, conjuring a mood of laidback languor that ran through the season – captured here by photographer Steve Harnacke and stylist Nicola Neri for Wallpaper*

By Jack Moss

-

Leonard Baby's paintings reflect on his fundamentalist upbringing, a decade after he left the church

Leonard Baby's paintings reflect on his fundamentalist upbringing, a decade after he left the churchThe American artist considers depression and the suppressed queerness of his childhood in a series of intensely personal paintings, on show at Half Gallery, New York

By Orla Brennan

-

Desert X 2025 review: a new American dream grows in the Coachella Valley

Desert X 2025 review: a new American dream grows in the Coachella ValleyWill Jennings reports from the epic California art festival. Here are the highlights

By Will Jennings

-

In ‘The Last Showgirl’, nostalgia is a drug like any other

In ‘The Last Showgirl’, nostalgia is a drug like any otherGia Coppola takes us to Las Vegas after the party has ended in new film starring Pamela Anderson, The Last Showgirl

By Billie Walker

-

‘American Photography’: centuries-spanning show reveals timely truths

‘American Photography’: centuries-spanning show reveals timely truthsAt the Rijksmuseum in Amsterdam, Europe’s first major survey of American photography reveals the contradictions and complexities that have long defined this world superpower

By Daisy Woodward

-

Tasneem Sarkez's heady mix of kitsch, Arabic and Americana hits London

Tasneem Sarkez's heady mix of kitsch, Arabic and Americana hits LondonArtist Tasneem Sarkez draws on an eclectic range of references for her debut solo show, 'White-Knuckle' at Rose Easton

By Zoe Whitfield

-

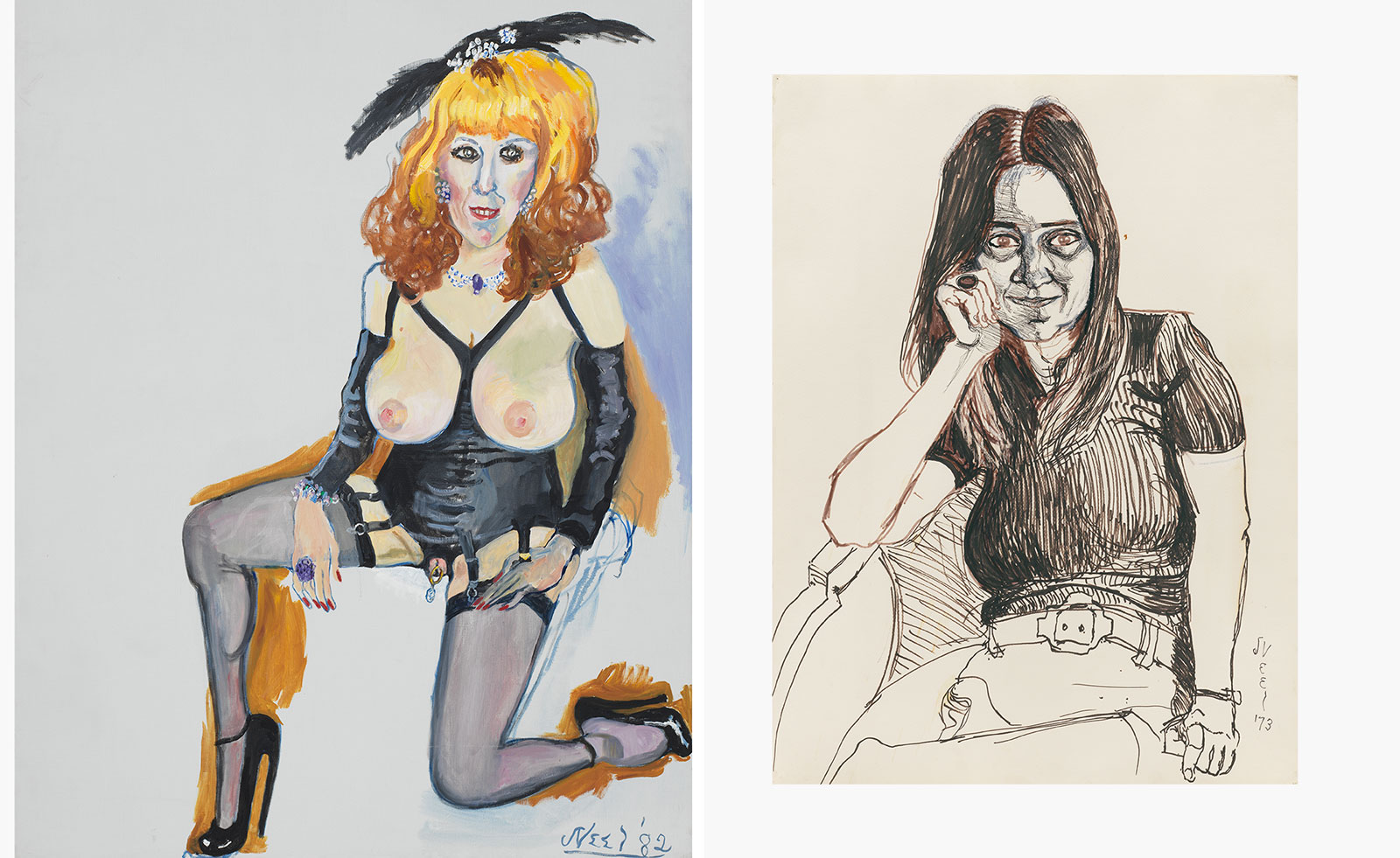

Alice Neel’s portraits celebrating the queer world are exhibited in London

Alice Neel’s portraits celebrating the queer world are exhibited in London‘At Home: Alice Neel in the Queer World’, curated by Hilton Als, opens at Victoria Miro, London

By Hannah Silver

-

‘You have to face death to feel alive’: Dark fairytales come to life in London exhibition

‘You have to face death to feel alive’: Dark fairytales come to life in London exhibitionDaniel Malarkey, the curator of ‘Last Night I Dreamt of Manderley’ at London’s Alison Jacques gallery, celebrates the fantastical

By Phin Jennings

-

Sundance Film Festival 2025: The films we can't wait to watch

Sundance Film Festival 2025: The films we can't wait to watchSundance Film Festival, which runs 23 January - 2 February, has long been considered a hub of cinematic innovation. These are the ones to watch from this year’s premieres

By Stefania Sarrubba