Why maverick Swiss curator Klaus Littmann is growing a forest in an Austrian stadium

This autumn, the Swiss art interventionist Klaus Littmann is filling a football stadium in the Austrian town of Klagenfurt with a full-grown forest. It is a free-access public art installation of Christo-like proportions that has had much of Austria buzzing for months.

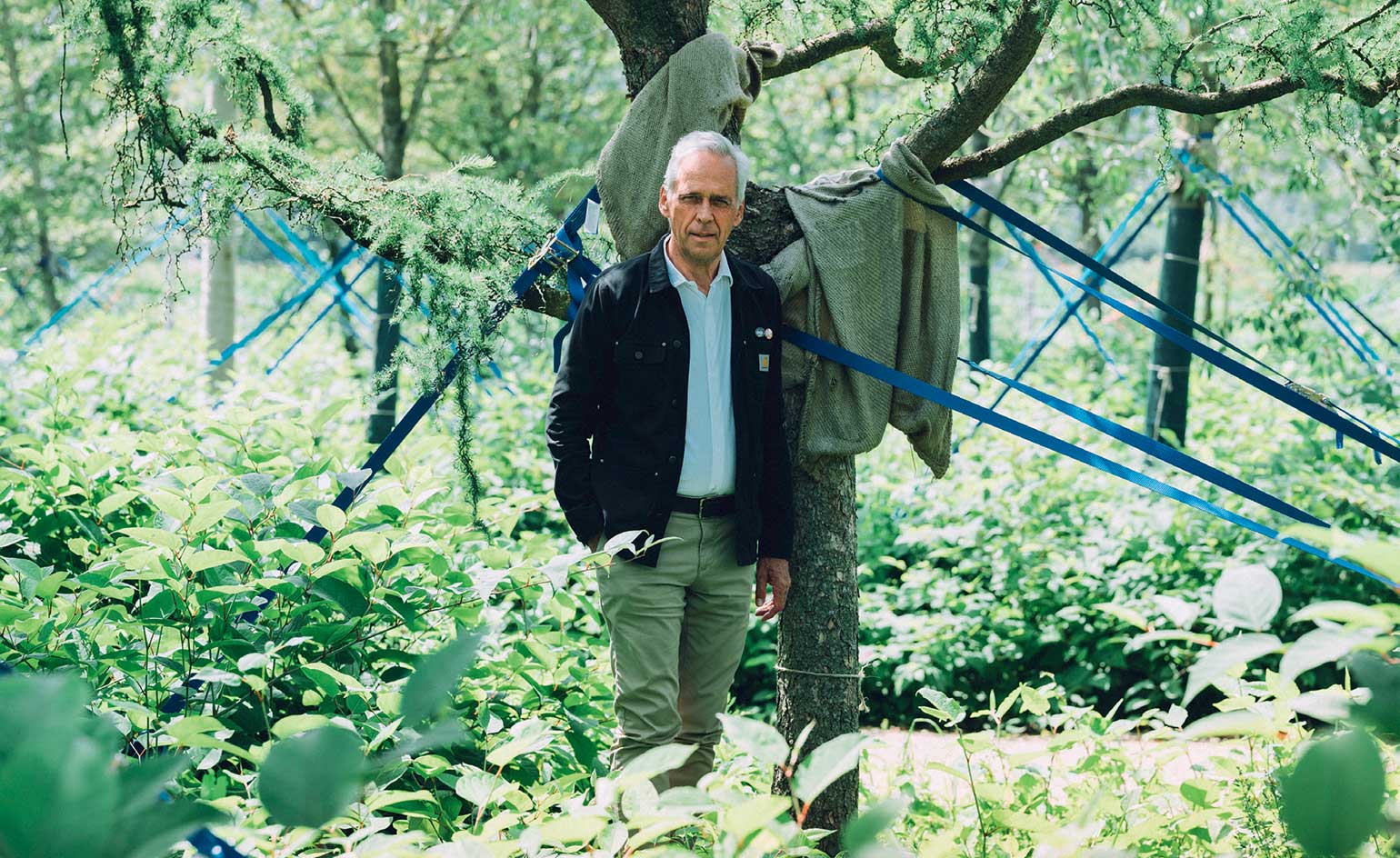

Littmann is not new to large-scale public projects. In 2018, for example, he floated 12 giant ‘art planets’ by a range of international artists above the city of Basel, visible from miles around. Born in 1951 in Riehen, he studied in the 1970s at the Düsseldorf Art Academy under Joseph Beuys and had his own gallery in Basel during the 1980s and 1990s, before turning his attention to ‘theme-oriented art exhibitions and interventions in the public arena’. He calls himself a ‘freelance mediator of contemporary art’, but actually prefers not to be pinned down by definitions: ‘When someone asks me: “Are you an artist?” I say: “No”, but if you don’t think like an artist, you couldn’t do these things.’

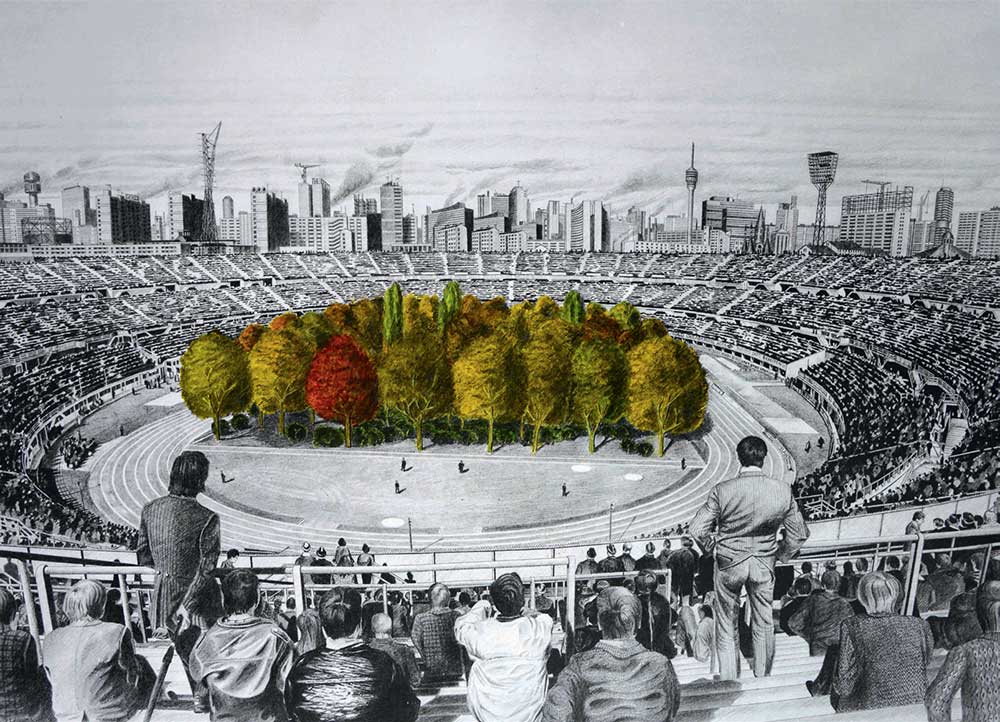

The Unending Attraction of Nature by Max Peintner, hand-coloured by Klaus Littman

Architect Max Peintner is a key figure of the Austrian environmentalist movement, who represented his country at the Venice Biennale in 1986 and whose work is in the collection of MoMA, New York. He created a pencil drawing in 1970/71, showing a crowd of onlookers gazing at a forest in a sports arena. Here, the original artwork has been hand-coloured by Klaus Littmann, setting the foliage in sharp contrast with the heavily industrialised cityscape in the background. ‘Peintner had the futuristic idea that what has been happening for centuries with animals in zoos could also happen with nature, that we might one day have to come into special spaces to observe it,’ says Littmann. The image continues to resonate half a century on, appearing in over 20 German textbooks, as well as publications in France, Denmark, Estonia, the Czech Republic and Hungary

This installation, his largest to date, was a long time in the making. It began 30-odd years ago when a friend showed him a book by the Austrian artist and architect Max Peintner containing a series of futuristic drawings from the 1970s. One of these images was The Unending Attraction of Nature (see above), picturing a stadium packed with spectators looking, spellbound, towards a fully-grown forest. ‘I was fascinated by this drawing and went to visit the artist,’ says Littmann. ‘I told him that I found it an unbelievable image and that it should be realised – I think he thought I was crazy.’

But the image stuck in Littmann’s mind and whenever a potential stadium came up for discussion in Switzerland or nearby, he pitched the idea. Finally, six years ago, he came across Wörthersee Stadium, a state-of-the-art facility with 32,000 seats in the Austrian town of Klagenfurt. After much negotiation, the local council agreed to let him have the use of the stadium for two months in 2019, free of charge. The€2.2m funding for the project he generated himself, almost exclusively through his own contacts and art patrons in Switzerland, including the Fondation Beyeler, but also through the sale of ‘tree adoptions’ at €5,000 each, which came with hand-coloured original graphic prints signed by both Littmann and Peintner.

Littmann enlisted the services of the highly acclaimed Swiss landscape architect Enzo Enea to bring Peintner’s vision to life. The biggest challenge was to find 300 trees from 19 varieties to make up the typical central European mini-forest on the pitch. ‘We needed to use what are called “schooled trees”,’ says Littmann. ‘That means mature trees that are about 13-14m tall, so about 30-40 years old, that have been repotted every four to five years, and don’t get stressed by moving.’ The trees will fill the confines of the pitch and their bases will be covered with a fine net, over which Enea’s team will construct a natural-looking forest floor. Around the edges will be a meadow area that goes right up to the stands. The whole thing will be floodlit at night and the foliage will change colour as autumn progresses.

The Unending Attraction of Nature, art intervention, 2019, Wörthersee Stadium Klagenfurt, Austria.

Visitors can enter the stadium, at no admission charge, and move freely around the stands to see the work from different perspectives, but the forest is not accessible. ‘What is really important to me in all my projects in public spaces is perception,’ says Littmann. ‘I want people to stand and look at it and ask themselves: “What am I seeing? What is it about? What does it mean for me?” I want it to provoke their sense of sight and what they are used to seeing. If that happens, then for me is the whole thing a success.’

Victor Hugo’s statement ‘Nothing is more powerful than an idea whose time has come’ could hardly be more appropriate in the case of For Forest. ‘This project triggers a great deal of discussion and raises a lot of questions,’ says Littmann. ‘How do we treat nature? How are forests managed? One criticism, for example, is: “Austria is full of forests, why do you need to put one in a stadium?” To which my answer is: “Yes, that is true, but what kind of forests are they? They are monocultures. The native mixed deciduous forest, which is incredibly important, is completely marginalised, although we depend on it, especially now in the context of climate change. The same problems as in the Amazon are here right on our doorstep. Immense areas of forests are dying out and being destroyed by disease and commercial forestry. This image brings these issues into focus.”’

Littmann says that, although he never set out to be deliberately radical with For Forest, the project has experienced a considerable amount of opposition, particularly from the far right (the local region is a stronghold of the populist Freedom Party of Austria), with verbal abuse and calls to ‘get the chainsaws out’. His original fascination with Peintner’s image was this ‘futuristic’ idea that ‘what makes us put animals in zoos could also happen to nature. But the current focus on climate change has given the drawing a new dimension. Perhaps it really had to take 30 years before it could be realised.’

A version of this article originally featured in the October 2019 issue of Wallpaper* (W*247)

INFORMATION

Until 27 October. forforest.net; klauslittmann.com

Wallpaper* Newsletter

Receive our daily digest of inspiration, escapism and design stories from around the world direct to your inbox.

-

Tour the best contemporary tea houses around the world

Tour the best contemporary tea houses around the worldCelebrate the world’s most unique tea houses, from Melbourne to Stockholm, with a new book by Wallpaper’s Léa Teuscher

By Léa Teuscher

-

‘Humour is foundational’: artist Ella Kruglyanskaya on painting as a ‘highly questionable’ pursuit

‘Humour is foundational’: artist Ella Kruglyanskaya on painting as a ‘highly questionable’ pursuitElla Kruglyanskaya’s exhibition, ‘Shadows’ at Thomas Dane Gallery, is the first in a series of three this year, with openings in Basel and New York to follow

By Hannah Silver

-

Australian bathhouse ‘About Time’ bridges softness and brutalism

Australian bathhouse ‘About Time’ bridges softness and brutalism‘About Time’, an Australian bathhouse designed by Goss Studio, balances brutalist architecture and the softness of natural patina in a Japanese-inspired wellness hub

By Ellie Stathaki

-

Remote Antarctica research base now houses a striking new art installation

Remote Antarctica research base now houses a striking new art installationIn Antarctica, Kyiv-based architecture studio Balbek Bureau has unveiled ‘Home. Memories’, a poignant art installation at the remote, penguin-inhabited Vernadsky Research Base

By Harriet Lloyd-Smith

-

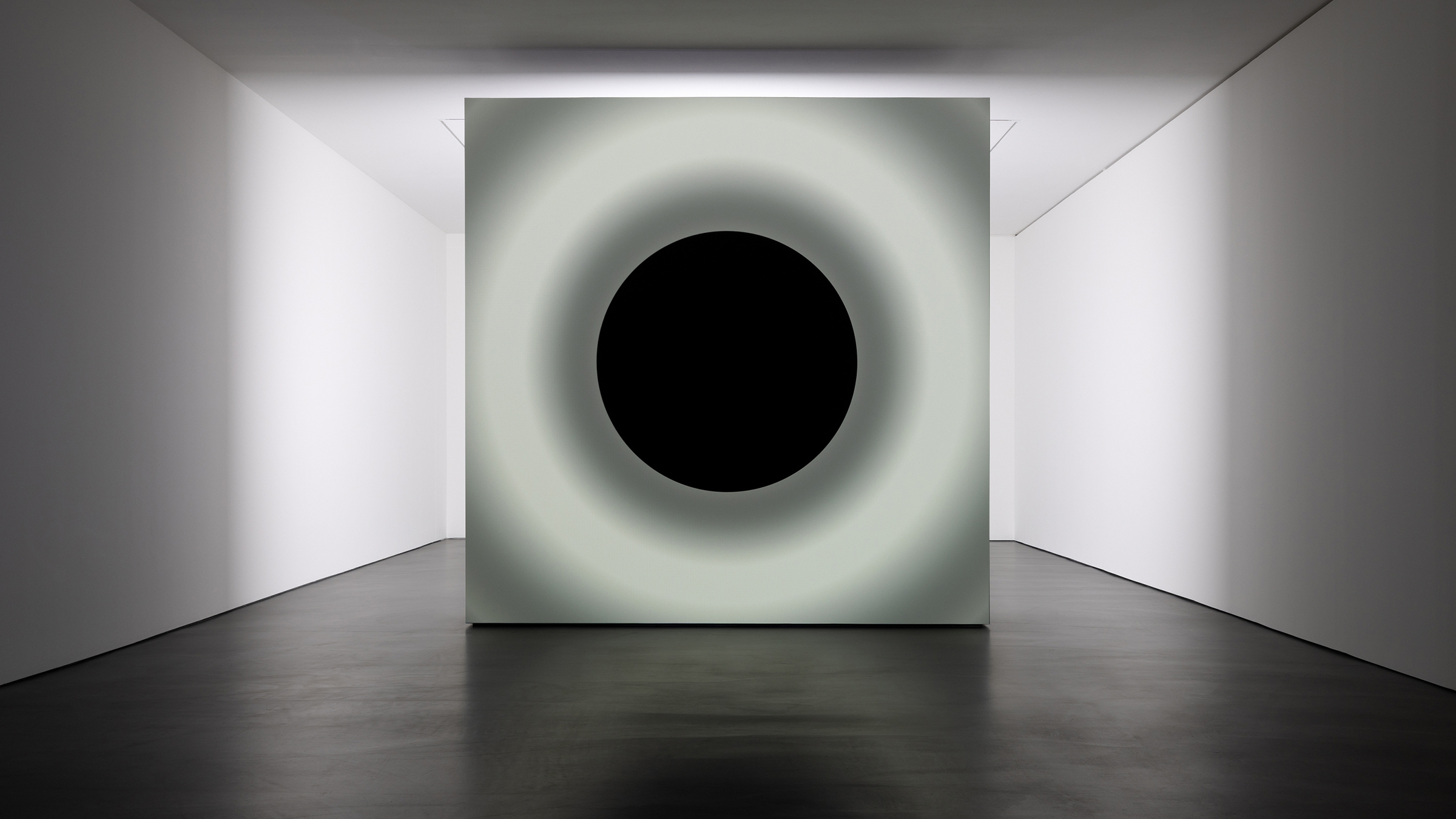

Ryoji Ikeda and Grönlund-Nisunen saturate Berlin gallery in sound, vision and visceral sensation

Ryoji Ikeda and Grönlund-Nisunen saturate Berlin gallery in sound, vision and visceral sensationAt Esther Schipper gallery Berlin, artists Ryoji Ikeda and Grönlund-Nisunen draw on the elemental forces of sound and light in a meditative and disorienting joint exhibition

By Harriet Lloyd-Smith

-

Cecilia Vicuña’s ‘Brain Forest Quipu’ wins Best Art Installation in the 2023 Wallpaper* Design Awards

Cecilia Vicuña’s ‘Brain Forest Quipu’ wins Best Art Installation in the 2023 Wallpaper* Design AwardsBrain Forest Quipu, Cecilia Vicuña's Hyundai Commission at Tate Modern, has been crowned 'Best Art Installation' in the 2023 Wallpaper* Design Awards

By Harriet Lloyd-Smith

-

Michael Heizer’s Nevada ‘City’: the land art masterpiece that took 50 years to conceive

Michael Heizer’s Nevada ‘City’: the land art masterpiece that took 50 years to conceiveMichael Heizer’s City in the Nevada Desert (1972-2022) has been awarded ‘Best eighth wonder’ in the 2023 Wallpaper* design awards. We explore how this staggering example of land art came to be

By Harriet Lloyd-Smith

-

Cerith Wyn Evans: ‘I love nothing more than neon in direct sunlight. It’s heartbreakingly beautiful’

Cerith Wyn Evans: ‘I love nothing more than neon in direct sunlight. It’s heartbreakingly beautiful’Cerith Wyn Evans reflects on his largest show in the UK to date, at Mostyn, Wales – a multisensory, neon-charged fantasia of mind, body and language

By Harriet Lloyd-Smith

-

The best 7 Christmas installations in London for art lovers

The best 7 Christmas installations in London for art loversAs London decks its halls for the festive season, explore our pick of the best Christmas installations for the art-, design- and fashion-minded

By Harriet Lloyd-Smith

-

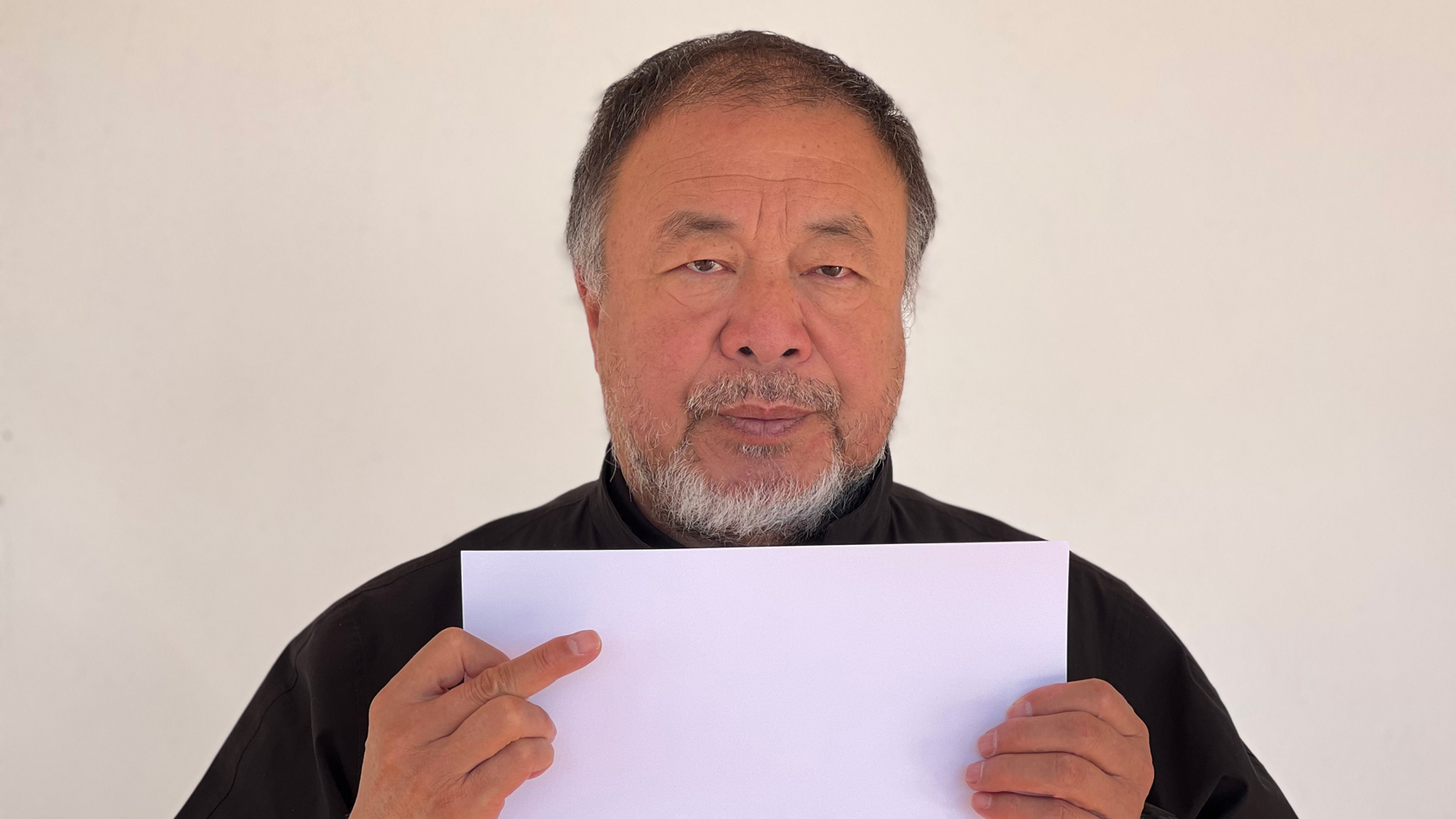

Ai Weiwei to sign blank sheets of paper with UV ink for Refugees International in London this weekend

Ai Weiwei to sign blank sheets of paper with UV ink for Refugees International in London this weekendTo mark Human Rights Day (10 December 2022), Ai Weiwei will take to Speakers' Corner in Hyde Park to sign sheets of A4 paper in UV ink, distributed free. We interview the artist to find out more

By TF Chan

-

Rafael Lozano-Hemmer’s Pulse Topology in Miami is powered by heartbeats

Rafael Lozano-Hemmer’s Pulse Topology in Miami is powered by heartbeatsRafael Lozano-Hemmer brings heart and human connection to Miami Art Week 2022 with Pulse Topology, an interactive light installation at Superblue Miami in collaboration with BMW i

By Fiona Mahon