Parallel universe: Laurent Grasso’s beguiling reinvention of a Corsican Beaux-Arts museum

The Palais Fesch, an imposing 19th century building on the waterfront of the Corsican capital of Ajaccio, houses France’s largest collection of Italian paintings outside the Louvre. There are works by Botticelli, Michelangelo, Titian, Veronese and many others – interspersed among portraits and busts of the island’s most illustrious family, the Bonapartes.

It’s not the most obvious setting for showing contemporary art. But this hasn’t stopped director Philippe Costamagna from staging exhibitions of unusual audacity. Following a much-lauded collaboration with American photographer Andres Serrano in 2014, Costamagna has now worked with French conceptual artist Laurent Grasso to reinvent the museum’s top floor.

Titled ’Paramuseum’, Grasso’s show at the Fesch combines paintings and sculptures from the museum’s collection and his own work in creative configurations. By challenging representations of political power and religious might, and blurring the boundaries between meteorology and myth, Grasso plunges his viewers into an oddly beguiling parallel universe.

On entering ’Paramuseum’, the viewer is greeted by a long wall with 43 historical portraits. Grasso had selected them for their subjects’ piercing gaze, and hung them so the 43 pairs of eyes are horizontally aligned. Their presence is made eerier by Grasso’s neons on the opposite wall, which show epoch-defining dates (among them the destruction of Pompeii and the 1755 Lisbon earthquake).

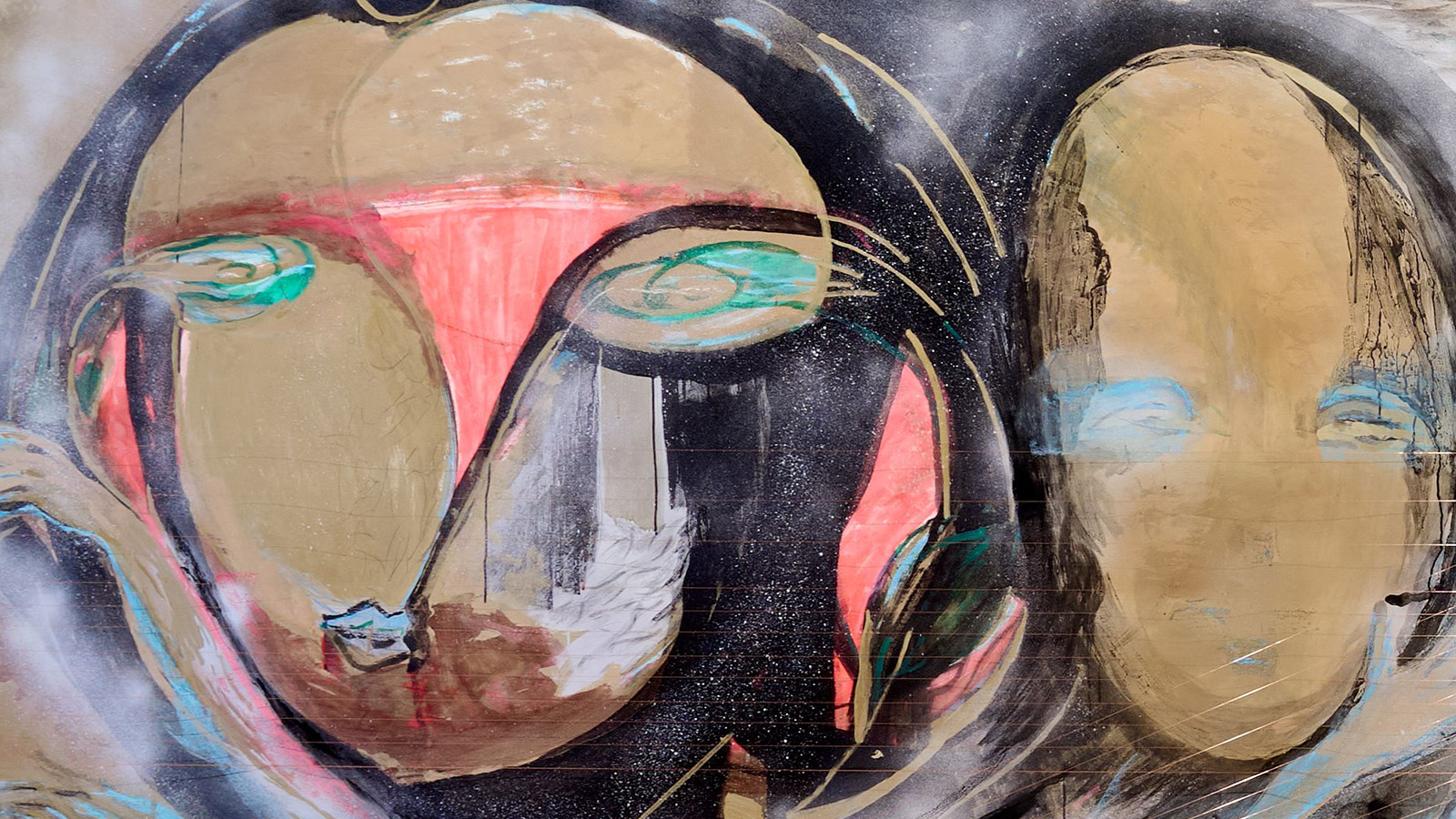

More eyes scrutinise the viewer throughout the show. Disembodied pairs, borrowed from the Fesch’s portraits, brim with enigma on new canvases. There are also images of ghostly saints, transferred from larger paintings onto silver-coated wooden blocks. Grasso has reversed the power dynamic of the usual art exhibition, and made his viewers into objects of the artworks’ gaze.

Old and new works are juxtaposed to stirring effect. One room sets 17th-century portraits of ecclesiastical portraits against Grasso’s marble sculpture, showing a heron whose beak is obstructed by an egg. Titled S.T. (short for ’sile tace’, which means ’keep silent’ in Latin), the piece nods to signs within the Vatican, and more broadly the church’s demands for silent obedience. This critical view of religion is then complicated by Grasso’s photograph of a priest and astronomer at work at the Vatican observatory.

Another room brings together historical busts of Napoleon’s father, brother, sister, brother-in-law and niece with a film by Grasso, featuring sculptures of fantastic beasts from the Garden of Bomarzo in Viterbo, Italy – a whimsical allegory for the enduring power of the Napoleonic legend.

Wallpaper* Newsletter

Receive our daily digest of inspiration, escapism and design stories from around the world direct to your inbox.

Further commenting on the allure of temporal power, Grasso presents a new film, Élysée, in the museum’s Grande Galerie. Shot in the French president’s office at the Palais de l’Élysée, it draws attention to furniture, fittings and day-to-day objects that have been gilded with gold, and uses the act of gilding as a metaphor for investing great power in a head of state.

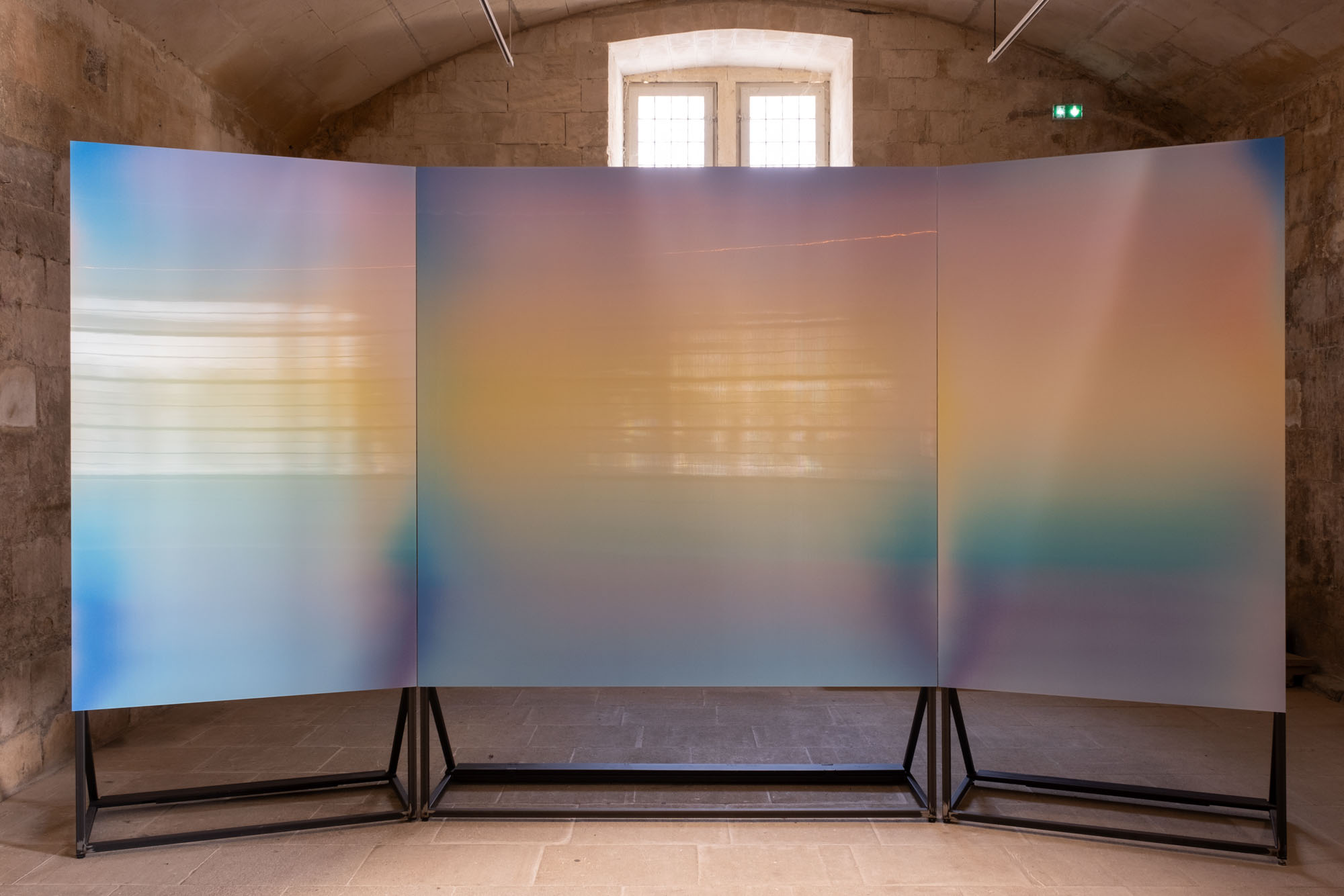

Elsewhere, Grasso’s best-known film, Soleil double, is on view. Twin suns are shown blazing down on the magnificent Museo della Civiltà Romana in Rome, in allusion to the legend of Nemesis, a dwarf star that would one day collide with our solar system and cause its destruction. A sculptural representation, consisting of two overlaid yellow neon circles, illuminates the room next door. It shares the space with a group of old landscape paintings, which Grasso had chosen for their aged, yellowed appearance. Under the neon circles’ golden glow, the paintings seem rejuvenated – just as the Palais Fesch has taken on a new life under Grasso’s masterful intervention.

The film draws its name from the Palais de l’Élysée, where the French president resides. Shot in the president’s personal office (called the Salon Doré), it draws attention to furniture, fittings and day-to-day objects that have been gilded with gold, simultaneously allegorising and questioning the act of investing great power in a head of state

One wall in the long central gallery has been lined with 43 paintings from the Italian Renaissance. Grasso selected them based on the sharpness of each subject’s gaze, and hung them so that each pair of eyes would be on the same horizontal line. The effect is made eerier by Grasso’s neon works on the opposite wall

Dotting the exhibition are silver canvases, painted with eyes taken from the portraits of the museum’s collection. By omitting the rest of their faces, Grasso forces the viewer to confront the sitters’ penetrating gaze

Grasso examines religious virtue and oppression by pairing four ecclesiastical portraits with a marble sculpture of his own. Depicting a heron whose beak has been obstructed by an egg, it seems to suggest both the ennobling and suffocating effects of silence

A pair of oils on gold foil. Pictured left: one of Grasso’s studies, Into the Past, showing a rout of knights staring at a dark sun. Right: Christ Blessing, by early Italian Renaissance painter Antoniazzo Romano

Grasso has shown himself as a master at the art of anachronism. Pictured left: the present-day Salon Doré is realised in a painting style of the 19th century. Right: the Hand of Justice (commonly found at the tip of French sceptres) is given a contemporary treatment in marble

A still from Grasso’s 2014 film, Soleil double shows twin suns blazing down on the magnificent Museo della Civiltà Romana in Rome. The unnerving sight alludes to Nemesis, a hypothesised dwarf star that would one day collide with the solar system and cause its destruction

Grasso’s Éclipse, a pair of overlaid neon circles, casts its golden glow on a room full of Italian landscape paintings which had yellowed over the years

INFORMATION

’Laurent Grasso: Paramuseum’ is on view until 3 October, with the support of Galerie Perrotin. For more information, visit the Palais Fesch-musée des Beaux-Arts website

Photography by Claire Dorn, courtesy of Palais Fesch-musée des Beaux-Arts, Ajaccio & Galerie Perrotin

ADDRESS

Palais Fesch-musée des Beaux-Arts

50-52 Rue du Cardinal Fesch

20000 Ajaccio

Corsica

TF Chan is a former editor of Wallpaper* (2020-23), where he was responsible for the monthly print magazine, planning, commissioning, editing and writing long-lead content across all pillars. He also played a leading role in multi-channel editorial franchises, such as Wallpaper’s annual Design Awards, Guest Editor takeovers and Next Generation series. He aims to create world-class, visually-driven content while championing diversity, international representation and social impact. TF joined Wallpaper* as an intern in January 2013, and served as its commissioning editor from 2017-20, winning a 30 under 30 New Talent Award from the Professional Publishers’ Association. Born and raised in Hong Kong, he holds an undergraduate degree in history from Princeton University.

-

This new Vondom outdoor furniture is a breath of fresh air

This new Vondom outdoor furniture is a breath of fresh airDesigned by architect Jean-Marie Massaud, the ‘Pasadena’ collection takes elegance and comfort outdoors

By Simon Mills

-

Eight designers to know from Rossana Orlandi Gallery’s Milan Design Week 2025 exhibition

Eight designers to know from Rossana Orlandi Gallery’s Milan Design Week 2025 exhibitionWallpaper’s highlights from the mega-exhibition at Rossana Orlandi Gallery include some of the most compelling names in design today

By Anna Solomon

-

Nikos Koulis brings a cool wearability to high jewellery

Nikos Koulis brings a cool wearability to high jewelleryNikos Koulis experiments with unusual diamond cuts and modern materials in a new collection, ‘Wish’

By Hannah Silver

-

‘The Black woman endures a gravity unlike any other’: Pharrell Williams explores diverse interpretations of femininity in Paris

‘The Black woman endures a gravity unlike any other’: Pharrell Williams explores diverse interpretations of femininity in ParisPharrell Williams returns to Perrotin gallery in Paris with a new group show which serves as an homage to Black women

By Amy Serafin

-

Miami’s new Museum of Sex is a beacon of open discourse

Miami’s new Museum of Sex is a beacon of open discourseThe Miami outpost of the cult New York destination opened last year, and continues its legacy of presenting and celebrating human sexuality

By Anna Solomon

-

Architecture, sculpture and materials: female Lithuanian artists are celebrated in Nîmes

Architecture, sculpture and materials: female Lithuanian artists are celebrated in NîmesThe Carré d'Art in Nîmes, France, spotlights the work of Aleksandra Kasuba and Marija Olšauskaitė, as part of a nationwide celebration of Lithuanian culture

By Will Jennings

-

‘Who has not dreamed of seeing what the eye cannot grasp?’: Rencontres d’Arles comes to the south of France

‘Who has not dreamed of seeing what the eye cannot grasp?’: Rencontres d’Arles comes to the south of FranceLes Rencontres d’Arles 2024 presents over 40 exhibitions and nearly 200 artists, and includes the latest iteration of the BMW Art Makers programme

By Sophie Gladstone

-

Van Gogh Foundation celebrates ten years with a shape-shifting drone display and The Starry Night

Van Gogh Foundation celebrates ten years with a shape-shifting drone display and The Starry NightThe Van Gogh Foundation presents ‘Van Gogh and the Stars’, anchored by La Nuit Etoilée, which explores representations of the night sky, and the 19th-century fascination with the cosmos

By Amy Serafin

-

Marisa Merz’s unseen works at LaM, Lille, have a uniquely feminine spirit

Marisa Merz’s unseen works at LaM, Lille, have a uniquely feminine spiritMarisa Merz’s retrospective at LaM, Lille, is a rare showcase of her work, pursuing life’s most fragile, transient details

By Finn Blythe

-

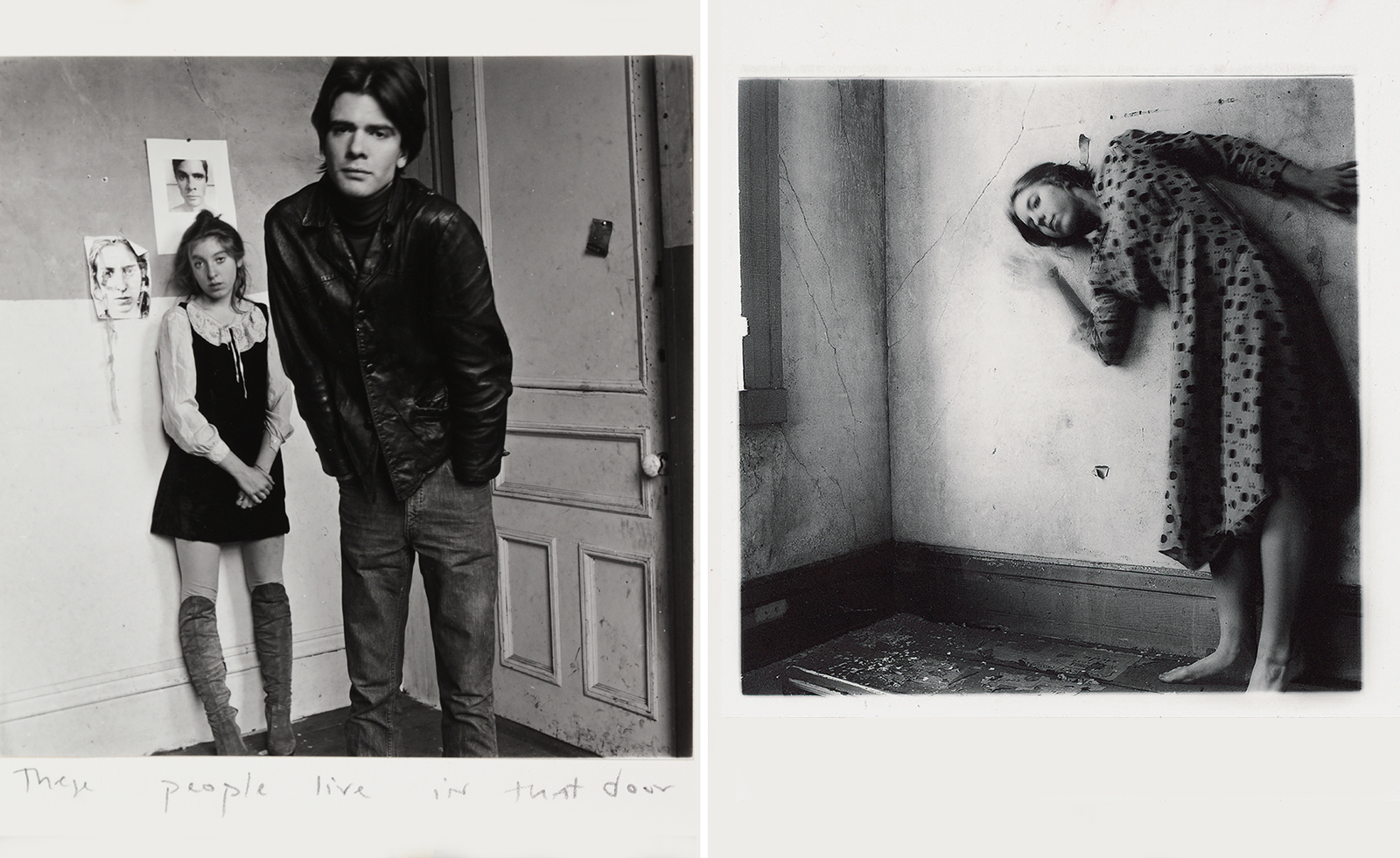

Step into Francesca Woodman and Julia Margaret Cameron's dreamy photographs in London

Step into Francesca Woodman and Julia Margaret Cameron's dreamy photographs in London'Portraits to Dream In' is currently on show at London's National Portrait Gallery

By Katie Tobin

-

Damien Hirst takes over Château La Coste

Damien Hirst takes over Château La CosteDamien Hirst’s ‘The Light That Shines’ at Château La Coste includes new and existing work, and takes over the entire 500-acre estate in Provence

By Hannah Silver