Life on Mars: Tom Sachs’ space adventures captured on film

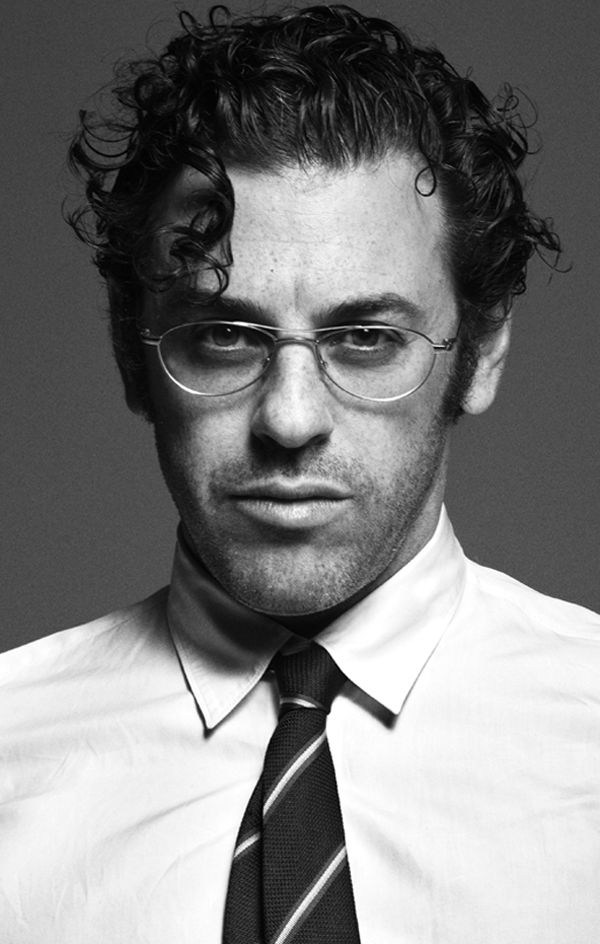

In the early aughts, filmmaker Van Neistat worked as a fabricator for Tom Sachs, notably on the artist’s massive foamcore model of Le Corbusier’s Unité d'Habitation and helped make the film (with his brother Casey) about Sachs’s mixed media Nutsy’s McDonald’s installation. Then from 2004 to 2010 the Neistat Brothers, as they were known professionally, took their own studio in Tribeca to focus on their films and an eponymous HBO series. During that time Sachs had launched the lunar journey of his Space Program at Gagosian Gallery in 2007, which the brothers visited as fans and later made into an episode for their show. So when Sachs called Van Neistat back to work on more films (beginning with Ten Bullets) shortly after the series premiered in the spring of 2010, it was as a collaborator, not an employee.

'It’s best when people graduate from the studio,' says Sachs. 'When Van came back for his postdoctoral work it was a much more even relationship.'

Over the ensuing years, the two embarked on a series of industrial films —Love Letter to Plywood, Space Camp, How To Sweep — that not only help to define the bricolage practices (in the vein of the Eames’ films for IBM and Polaroid) that define Sachs’s studio, but also lay out the narrative fabric for their new feature, A Space Program, which centers around the artist’s 2012 Mars mission installation and performance at the Park Avenue Armory.

'All three of those movies are cut into A Space Program and we feel like those are the bones for the stock for the chicken soup,' explains Sachs, admitting, 'the way we filmed at the Armory was a total clusterfuck and we were totally unprepared, we didn’t have enough time, and it was all shot really casually.'

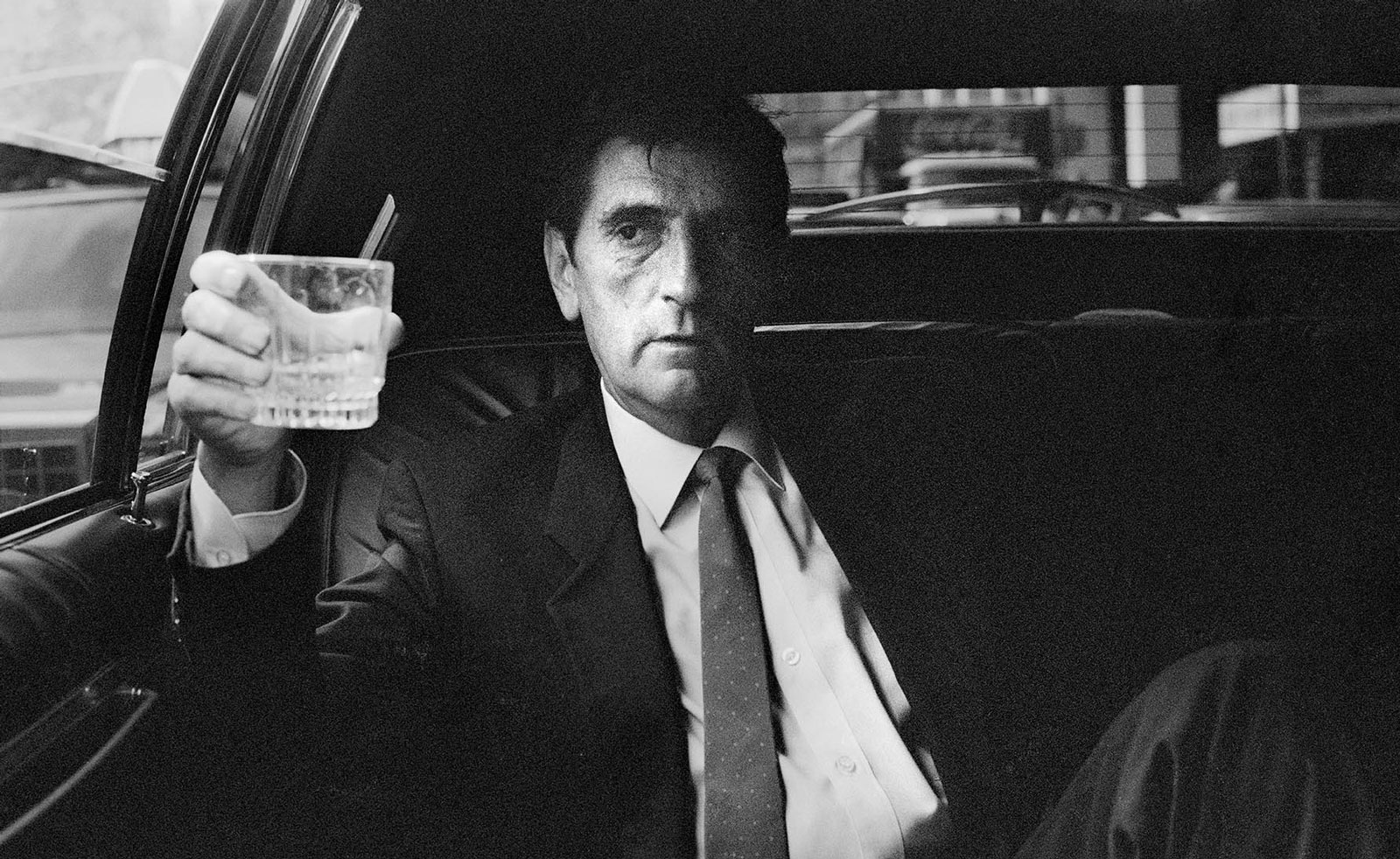

However, by making a series of post-production segments — on the human heart (and it’s relationship to the brain, narcissism and decision-making) and cartoons about earth re-entry on Gagosian Gallery letterhead (shot the day before they shipped the film to SXSW for its world premiere last spring) — they managed to shape the film into a quirky quest narrative whose sequence lines up shot for shot (in parts) with Al Reinert’s 1989 Apollo Mission documentary For All Mankind.

'When I was shooting at the Armory I was mimicking all the shots I could remember from that movie. The shot of the yellow shoes walking toward the scissor lift is stolen right from For All Mankind,' says Neistat, comparing it to the harmony of the Dark Side of the Moon and The Wizard of Oz. 'I just took advantage of how busy Tom was to do whatever I wanted and then after the show was installed there were multi-year arguments over shots he wanted. Tom spent $1,000 to get the boombox out of the studio to shoot 40 frames, and I was fighting him the whole way, but in the end he was right.'

With footage stretching between 2007 and 2015, the 102 minute film retains the Neistatian/Sachsian footprint while moving in on the territory of Michel Gondry. In this case, it’s a love story to bricoleurs and handmade sculpture told through the lens of a Martian landing with all the attendant neuroses, soil samplings, and tea ceremonies that go along with DIY space travel.

'We love these artists that make these really brilliant art movies that are sumptuous and beautiful and really painful to watch. But one thing we wanted to do was to respect the time of the audience and observe that beginning, middle, and end,' says Sachs, who will open his Tom Sachs: Tea Ceremony installation (the subject of their next film) at the Noguchi Museum next week, followed by Tom Sachs: Boombox Retrospective, 1999-2016 (another potential film subject) at the Brooklyn Museum in April. 'One of the foundations of the studio is eliminating the meanings of art, so you don’t need texts on the wall to explain what’s going on. That’s one of the things we agree on more than anything else. I love conceptual art and challenging ideas and everything else, but that’s not a culture that I come from, I don’t come from an art family; I come from a baseball and shopping kind of family. That’s my background.'

For Neistat, if A Space Program succeeds it will do so because it lives up to the spirit of those early Eames films, most notably their seminal 1972 short on the Polaroid SX-70.

'It was made for the employees of Polaroid and it explains exactly how the SX-70 works,' says Neistat. 'They’re able to explain to anyone, to a child, how the Polaroid film develops and works. They’re able to explain how the iris and light detector talk to each other through circuit boards and they’re able to put humanity in it. It can make you cry and it’s about a camera. It’s a masterpiece. Subconsciously we’re trying to do just that...with the Space Program ingredient.'

It's a love story to bricoleurs and handmade sculpture told through the lens of a Martian landing with all the attendant neuroses, soil samplings, and tea ceremonies that go along with DIY space travel

For director Van Neistat, if A Space Program succeeds it will do so because it lives up to the spirit of early Eames films

It was important to Sachs that the film have a beginning, middle and end for audiences of all kinds: 'One of the foundations of the studio is eliminating the meanings of art, so you don’t need texts on the wall to explain what’s going on'

INFORMATION

A Space Program will premiere at New York’s new Metrograph theatre on 18 March, with limited national rollout through May

Photography: Courtesy of Zeitgeist Films

Wallpaper* Newsletter

Receive our daily digest of inspiration, escapism and design stories from around the world direct to your inbox.

-

All-In is the Paris-based label making full-force fashion for main character dressing

All-In is the Paris-based label making full-force fashion for main character dressingPart of our monthly Uprising series, Wallpaper* meets Benjamin Barron and Bror August Vestbø of All-In, the LVMH Prize-nominated label which bases its collections on a riotous cast of characters – real and imagined

By Orla Brennan

-

Maserati joins forces with Giorgetti for a turbo-charged relationship

Maserati joins forces with Giorgetti for a turbo-charged relationshipAnnouncing their marriage during Milan Design Week, the brands unveiled a collection, a car and a long term commitment

By Hugo Macdonald

-

Through an innovative new training program, Poltrona Frau aims to safeguard Italian craft

Through an innovative new training program, Poltrona Frau aims to safeguard Italian craftThe heritage furniture manufacturer is training a new generation of leather artisans

By Cristina Kiran Piotti

-

Leonard Baby's paintings reflect on his fundamentalist upbringing, a decade after he left the church

Leonard Baby's paintings reflect on his fundamentalist upbringing, a decade after he left the churchThe American artist considers depression and the suppressed queerness of his childhood in a series of intensely personal paintings, on show at Half Gallery, New York

By Orla Brennan

-

Desert X 2025 review: a new American dream grows in the Coachella Valley

Desert X 2025 review: a new American dream grows in the Coachella ValleyWill Jennings reports from the epic California art festival. Here are the highlights

By Will Jennings

-

This rainbow-coloured flower show was inspired by Luis Barragán's architecture

This rainbow-coloured flower show was inspired by Luis Barragán's architectureModernism shows off its flowery side at the New York Botanical Garden's annual orchid show.

By Tianna Williams

-

‘Psychedelic art palace’ Meow Wolf is coming to New York

‘Psychedelic art palace’ Meow Wolf is coming to New YorkThe ultimate immersive exhibition, which combines art and theatre in its surreal shows, is opening a seventh outpost in The Seaport neighbourhood

By Anna Solomon

-

Wim Wenders’ photographs of moody Americana capture the themes in the director’s iconic films

Wim Wenders’ photographs of moody Americana capture the themes in the director’s iconic films'Driving without a destination is my greatest passion,' says Wenders. whose new exhibition has opened in New York’s Howard Greenberg Gallery

By Osman Can Yerebakan

-

20 years on, ‘The Gates’ makes a digital return to Central Park

20 years on, ‘The Gates’ makes a digital return to Central ParkThe 2005 installation ‘The Gates’ by Christo and Jeanne-Claude marks its 20th anniversary with a digital comeback, relived through the lens of your phone

By Tianna Williams

-

In ‘The Last Showgirl’, nostalgia is a drug like any other

In ‘The Last Showgirl’, nostalgia is a drug like any otherGia Coppola takes us to Las Vegas after the party has ended in new film starring Pamela Anderson, The Last Showgirl

By Billie Walker

-

‘American Photography’: centuries-spanning show reveals timely truths

‘American Photography’: centuries-spanning show reveals timely truthsAt the Rijksmuseum in Amsterdam, Europe’s first major survey of American photography reveals the contradictions and complexities that have long defined this world superpower

By Daisy Woodward