Light box: a fresh perspective on Santiago Barberi Gonzalez’s marvel-filled Wunderkammer

In the rarefied world of crocodile-skin handbags, Santiago Barberi Gonzalez is king. There’s no happier place for him than the floor of a Nancy Gonzalez shop, selling uppercrust consumers his mother’s designs for women – or doing the same in one of his own boutiques for men. His private domain is another story.

Few have crossed the threshold of his pied-à-terre in New York, a one-bedroom eyrie on Fifth Avenue in Midtown Manhattan. In this modestly scaled, richly imagined place, the Colombian-born accessories tycoon devotes himself to art. It speaks to him like family from every wall, ceiling, floor and window, even the bathrooms and closets. To Barberi Gonzalez, the works also conduct a visual conversation with each other – and with the city beyond his several glass walls.

In the open space that joins his living and dining areas, floor-to-ceiling windows on two sides make it hard to tell where the outside ends and the apartment begins. Skyscrapers and sculptures constantly seem to trade places amid an astonishing number of paintings, photographs, drawings and other curiosities. Strips of LEDs recessed in the ceiling each cast a different shade of white light on individual artworks. At night, he says, ‘This apartment is magnificent.’

Santiago Barberi Gonzalez sits on ‘Hieronymus Wood’ by Konstantin Grcic beside an 18th-century celestial bronze globe and a pre-Columbian clay sphere, sandwiched by a pair of Regis Royant armchairs

Barberi Gonzalez has impeccable taste, in his Balmain or Dior Homme clothing, his décor, and his art. One of several works he owns by Joseph Kosuth is a yellow neon text that symbolises his personal aesthetic. It says, ‘Neither appearance nor illusion’, and is a brighter colour than anything else in the apartment, which has a palette that runs from white and silver to grey and black. Authenticity means more to him than market value. He’s not after trophies. The art he buys is neither very flashy nor very large. He looks for seminal works, in perfect condition, by artists who make him think. And he never buys only one work by each. ‘That,’ he says, ‘would be a souvenir.’ As long as they’re involved with language, numbers, codes, the passage of time or displacement, he’ll be in pursuit.

‘When I collect an artist,’ he says, ‘I do it cohesively and constantly. Nothing gets away.’ He’ll wait years for the right piece to come along and fill a hole that he feels diminishes his collection. ‘I don’t have a great John Baldessari,’ he moans. ‘It’s a very big problem. If I have to pay triple for the right piece, then I will.’

Barberi Gonzalez says that his first year as a collector was an unmitigated disaster. He bought indiscriminately, a novice currying favour from dealers. In 2007, he read the autobiography of Count Giuseppe Panza di Biumo, whose legendary collection of postwar American art is now divided between the Guggenheim New York and MOCA in Los Angeles.

Through the concierge of the Four Seasons Milan, a hotel he frequents on business, the eager Barberi Gonzalez contacted Panza, who was charmed enough to give him two full days of mentoring. They changed his life. ‘I learned everything from him,’ says Barberi Gonzalez. After that, he didn’t try going to galleries, auctions or art fairs alone. Through his family, and his business, he had the wherewithal to tap the talents of experts as consultants. One curator was Simon Castets, who worked with Barberi Gonzalez for four years before becoming director of the Swiss Institute in New York.

‘Santiago is a very fast learner with an extravagant, ebullient personality, very driven,’ says Castets. ‘It wouldn’t be unusual for him to sit in a gallery and talk about an artist for hours, and people remember that kind of commitment. He does a lot of research and thinks about things a long time, so every purchase is significant.’

Barberi Gonzalez picked up the camera himself when we visited his apartment, zooming in on this Jenny Holzer work, from her ’Survival Series: Protect Me From What I Want’, 1983-85 and offering a glimpse of his crocodile shoes

Castets was with Barberi Gonzalez in 2010 on his first trip to China. When a 1960s video sculpture by Nam June Paik appeared at an art fair in Hong Kong, Barberi Gonzalez wanted it so badly that it gave him heartburn. ‘When it hurts,’ he says, holding his stomach in mock pain, ‘I buy.’

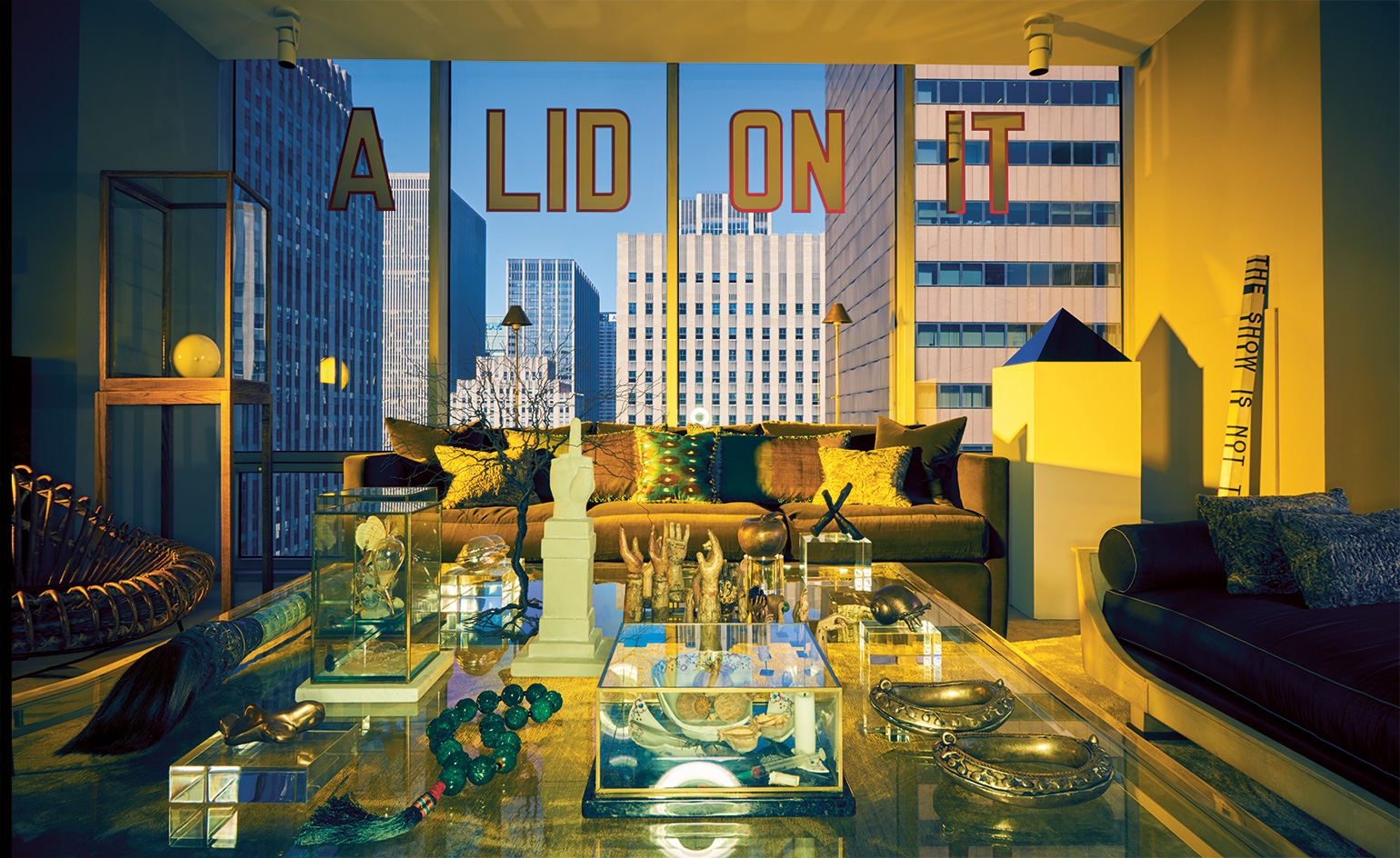

Probably the most valuable piece in his apartment is the only black pyramid ever made by John McCracken, the American minimalist best known for lacquered monoliths. The pyramid sits on a plain white platform in front of windows where vinyl letters by Lawrence Weiner spell out ‘A LID ON IT’. Also in front of those windows, which overlook the Rockefeller Center, is the sculpture The Head of Plato by James Lee Byars. ‘I’m geared more by curiosity than taste or culture,’ he says. ‘Plato is the philosopher who posed the most questions, questions that never had answers. It’s better to create questions. Who wants answers?’

Barberi Gonzalez left Cali, Colombia, for boarding school in America at 11 ‘for security reasons’, he says. After earning an undergraduate degree at Babson College in Boston, he took a master’s in art history and fashion marketing at the Savannah College of Art and Design in Georgia. His final thesis was his business plan for Nancy Gonzalez. In 1998, while he was still in school, that plan won him and his mother an order for handbags from Bergdorf Goodman. Since then, Barberi Gonzalez has built Nancy Gonzalez into a global enterprise. More recently, he opened a brand new Nancy Gonzalez shop at Harrods. Today, he’s the public face of both companies.

What about his personal life? His work and his collecting habits keep him on the road so often that he’s only in New York for 80-100 days a year. He doesn’t socialise or go to private views at galleries, and doesn’t join exclusive, curator-led tours of museums, either. Barberi Gonzalez prefers to walk with an audio guide. ‘If I ever open a foundation,’ he says, ‘I would pay for all the audio guides in all the museums. It’s so sad when I go to a show and it doesn’t have one.’

Most of his free time is dedicated to researching the art and furniture he craves as much as sleep. Much of it is from the 1960s and 1970s, but he also buys work by younger, internationally known contemporary artists like Ugo Rondinone, Carol Bove, the Campana brothers and Elmgreen & Dragset. Twice a year he empties the apartment and brings in a whole new set from storage. ‘The greatest luxury,’ says the man who sells ‘precious skin’ bags for thousands of dollars apiece, ‘is choice and versatility.’

Yet when I reach for one of eight unique wooden chairs surrounding an elliptical dining table with a lacquered goatskin top by Aldo Tura, Barberi Gonzalez says, ‘Let’s sit in here,’ indicating two dark sofas from Carlos Mota in the living room. One is bookended by an exceedingly rare pair of 18th-century whale tusks. The dining chairs, he says, are Chinese and 2,000 years old.

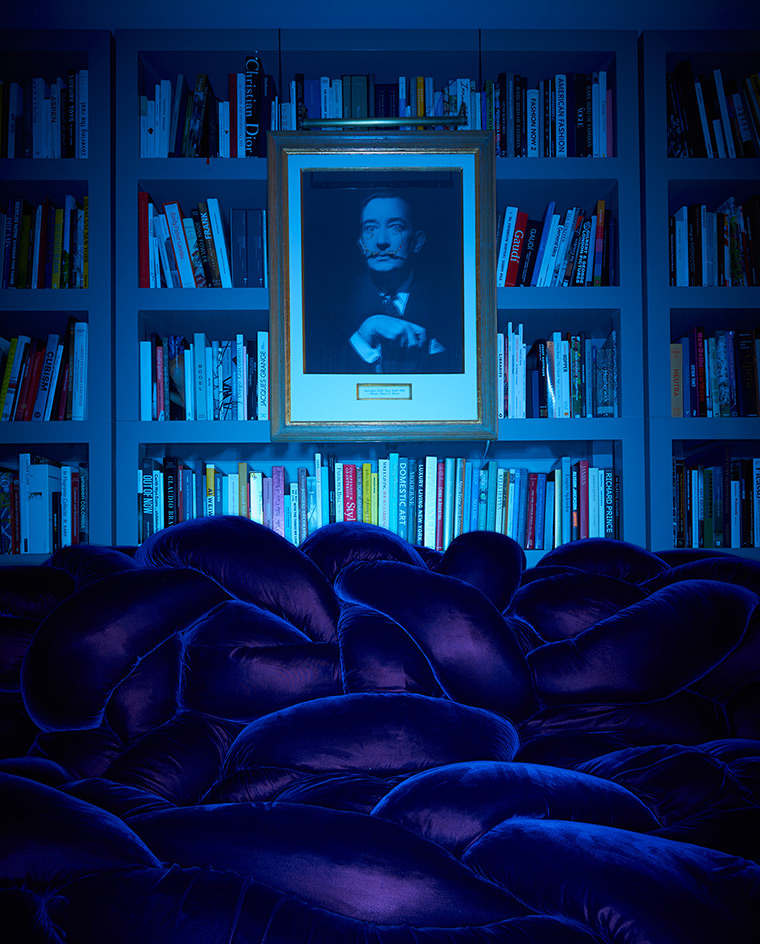

In Barberi Gonzalez’s New York apartment, ’Le surrealisme c’est moi! (Portrait of Salvador Dalí with jewels and tears, after Horst)’, by Francesco Vezzoli, hangs above a ’Boa’ sofa by Fernando and Humberto Campana, for Edra

He must be exaggerating, but that seems uncharacteristic for a man so fastidious that he orders his white Charvet shirts with the left cuff longer than the right to hide his typically large watch, and unlikely for a man with a fixation on time. In the living room, a small black canvas by On Kawara painted with the date, June10.2004 in white, corresponds, more or less telepathically, with photographs of timepieces by the Belgian conceptualist Kris Martin in the bedroom, opposite a black-and-white photograph of the sea made by Hiroshi Sugimoto using a super-long exposure.

The chairs actually date from the Qing dynasty, which lasted from 1644 to 1911. In 2007, artist Ai Weiwei brought them in a group of 1,001, with 1,001 Chinese people, to the 12th edition of Documenta, an international art show that occurs every five years. ‘I wanted to buy them all,’ Barberi Gonzalez says – a clue to the size of his ambition.

Not everyone living in a New York high-rise would have the guts to install a sculpture weighing nearly a ton as close to his Fifth Avenue windows as Barberi Gonzalez did with Antony Gormley’s Butt, a rusted steel brick sculpture that suggests a burdened man contemplating a leap. ‘It’s kind of decrepit and sad,’ he says. ‘Sad’ is a word he also uses to describe Topic, the word painted on faded burgundy fabric by Ed Ruscha. 'It's divino!' Barberi Gonzalez exclaims. 'The most elegant Ruscha, bleached and sad. It talks to me.'

As originally featured in the November 2016 issue of Wallpaper* (W*212)

In the dining room are eight Qing Dynasty chairs from Ai Weiwei’s 2007 Fairytale project for Documenta 12, a table by Aldo Tura, Joseph Kosuth’s neither appearance nor illusion, Franz West’s Nippes 9 and Iguazu by Wolfgang Tillmans. There are also works by On Kawara, Louise Lawler, Jenny Holzer and Michele Oka Doner

In the living room, affixed to the window, is Lawrence Weiner’s A Lid On It. On the left is James Lee Byars’ The Head of Plato, while on the right is Black Pyramid by John McCracken and a daybed by André Arbus. On the table, amid the collection of antique hands, chinese jade objects, and pre-Columbian ceremonial leg bracelets, is a wire tree sculpture by Pablo Avilla and a middle finger marble sculpture by Maurizio Cattelan. Barberi Gonzalez envisions this as his own cabinet of curiosities, and the carefully curated ’mini-show’ also includes objects by Jean Luc Moulene, Not Vital, Claude Lalanne and Michelle Oka Doner

Left: in the library, a ’Diu Piu’ chair by Nanda Vigo is beside a cast sculpture by Raqib Shaw (on top of an occasional stool by Pierre Charpin) and an Arredoluce Monza Triennale floor lamp by Gino Sarfatti. Right: Topic by Ed Ruscha sits above a bar cabinet by Batistin Spade with a ceramic sculpture of pre-Columbian origin

Left: in the library, Francesco Vezzoli’s Le surrealisme c’est moi! (Portrait of Salvador Dalí with Jewels and Tears, after Horst) holds court with the ’Boa’ sofa, by Fernando and Humberto Campana and Taryn Simon’s Black Square X series. Elsewhere, Joseph Kosuth’s Titled (A.A.I.A.I) [Meanin][Sp] looms large over objects by Elmgreen & Dragset, Michael Anastassides, Pierre Charpin and Nanda Vigo. Right: in the foyer, hung clockwise from top left, Auction II; Untitled; Aftermath; and Bulbs, all by Louis Lawler. In foreground, Camisas, by Doris Salcedo

Left: in the kitchen, Ivan Argote’s Excerpts: Ohh, is this a new end? stands next to Martino Gamper’s ‘Post Mundus’ chairs and Piero Lissoni’s ‘Funghetti Tavoli Alti’ table. Right: in the bedroom, Anne Collier’s Stock Photography (Gestures) is on the wall above a ‘Banquete’ alligator chair by the Campana brothers, while the Gilbert Rohde chest of drawers has a collection of neolithic bangles on top

In the bedroom, above the bed, is Welsh artist Cerith Wyn Evans’ In Which Something Happens All Over Again for the Very First Time (2006) and Belgian conceptualist Kris Martin’s photographs of timepieces

Left: in the foyer, Mother, by Maurizio Cattelan, and Camisas, by Doris Salcedo. Right: in the dining room, Haegue Yang’s Sonic Rotating Oval – Brass and Nickel Plated #20 looks out to the New York skyline. A pair of ’Rita’ chairs by Martino Gamper flank the adored, by Ugo Rondinone

INFORMATION

For more information, visit Santiago Gonzalez's website

Wallpaper* Newsletter

Receive our daily digest of inspiration, escapism and design stories from around the world direct to your inbox.

-

The Lighthouse draws on Bauhaus principles to create a new-era workspace campus

The Lighthouse draws on Bauhaus principles to create a new-era workspace campusThe Lighthouse, a Los Angeles office space by Warkentin Associates, brings together Bauhaus, brutalism and contemporary workspace design trends

By Ellie Stathaki

-

Extreme Cashmere reimagines retail with its new Amsterdam store: ‘You want to take your shoes off and stay’

Extreme Cashmere reimagines retail with its new Amsterdam store: ‘You want to take your shoes off and stay’Wallpaper* takes a tour of Extreme Cashmere’s new Amsterdam store, a space which reflects the label’s famed hospitality and unconventional approach to knitwear

By Jack Moss

-

Titanium watches are strong, light and enduring: here are some of the best

Titanium watches are strong, light and enduring: here are some of the bestBrands including Bremont, Christopher Ward and Grand Seiko are exploring the possibilities of titanium watches

By Chris Hall