Looming large: Conrad Shawcross on his great summer of immersive installations

The work of young British sculptor Conrad Shawcross is looming large and small in London this summer, as part of multiple gallery shows and as permanent fixtures as he emerges as a public art A-lister. His large-scale immersive installation The Dappled Light of the Sun has just been plugged into the Annenberg Courtyard of the Royal Academy on London's Piccadilly as part of it's annual Summer Exhibition (Shawcross it the Academy's youngest member).

The massive sculpture is five conjoined 'clouds,' made up of thousands of tetrahedrons built in steel - all 30 tons and seven-and-half miles of it. Standing six metres tall, visitors to the RA can wander underneath Shawcross' cloudscape and consider how chaos and beauty can be generated out of perfect order and geometry.

Opening on June 10 at the Victoria Miro gallery, North London branch, is an exhibition of smaller scale Shawcross works, mostly studies for Paradigm, his monumental sculpture to be installed outside the new Francis Crick Institute in Kings Cross. Paradigm is a 14 m-tall twisting stack of weathered steel tetrahedrons, which increase in scale as they push skywards. It is one metre wide at street level but five metres wide at its summit.

In April this year, Shawcross' Three Perpetual Chords, a series of giant steel loops, landed in South London's Dulwich Park, replacing Barbara Hepworth's Two Forms Divided Circle, which was stolen in 2011. And further afield, the New Art Centre, Roche Court in Wiltshire is showing a series of Shawcross works, inside and out, until July 26.

We spoke to an understandably frayed Shawcross about his busy year...

Wallpaper*: You're having an incredible year in London. Are you over the hump in terms of just getting everything done?

Conrad Shawcross: Yeah, pretty much. We have just finished the installation at the Royal Academy. We had to work at night using cranes.

W*: And how much was all this grand strategy and how much accident?

CS: Well, in the art world things get delayed and moved around, so you hedge your bets and line up as many things as you can. But suddenly all these things seem to have come at once so it's been a perfect storm.

W*: How have you managed to get the Miro show together with everything else going on?

CS: Miro gallery is kind of a supporting show. It's mostly a series of studies for Paradigm that will be installed in King's Cross. And there are a couple of other works called Manifold, which are really studies of how music decays into silence.

W*: You use the tetrahedron as a literal and conceptual building block, an essential building block?

CS: Well, to be honest, it's a very awkward building block. The Greeks thought of the tetrahedron as the essence of matter, indivisible matter. But if you build with them, they radiate out and bifurcate, like branches of a tree. It's irrational. The closest example is something like neural pathways in the brain.

W*: Do you use computer modelling when devising these sculptures?

CS: Yes, they need to be closely engineered and I work with a company called Structure Workshop on the modelling.

W*: You're not an artist who hands over the production side to other people. You don't do it all yourself though?

CS: No, with the RA commission we could only do about 20 per cent of it in the studio. And we worked out it would involve 12 and half years of welding work for one man so we needed help. It was an epic job.

W*: And you can't really improvise as you are going along?

CS: Not really. A little bit, but the sculptures have to work structurally, the engineering has to be right and they have to be safe.

W*: What happens to The Dappled Light of the Sun after the RA Summer Show?

CS: It's for sale, so hopefully someone will buy it. It's designed to last for ever. It's a shelter; efficient, interactive.

W*: You now have permanent installations in public spaces. The works in Dulwich Park for instance, do you think about them differently to the gallery pieces?

CS: The pieces in Dulwich Park are huge but approachable and tactile. Children can play inside them, lovers can sit on them. It's very moving to watch people using them actually. And they will look different from season to season because they polish in the summer as they are used and rust over in the winter.

W*: And the work outside the Francis Crick Institute is a really huge work. It will become part of the cityscape.

CS: Yeah, that is a different kind of thing. It's monumental, 14-metres tall, and will become a real part of the city. It's called Paradigm because it's about how new paradigms are built on old ones until the whole thing collapses. And the sculpture is engineered to be as tall as it can be before toppling over.

At once materially heavy and conceptually light, geometrical and philosophical, 'The Dappled Light of the Sun' is a meticulously-constructed and extremely powerful structure. Courtesy of the Royal Academy of Arts

Shawcross explains: 'The Greeks thought of the tetrahedron as the essence of matter, indivisible matter. But if you build with them, they radiate out and bifurcate, like branches of a tree. It's irrational.' Courtesy of the Royal Academy of Arts

The Dappled Light of the Sun in production. Courtesy the artist and Victoria Miro Gallery, London

Assembled using a crane, the piece begins to take shape before taking pride of place in the RA's courtyard. Courtesy the artist and Victoria Miro Gallery, London

The installation uses the tetrahedron as a literal and conceptual building block - an essential, and 'very awkward' - building block. Courtesy the artist and Victoria Miro Gallery, London

Structure Workshop helped with the production. 'We worked out it would involve 12 and half years of welding work for one man,' said Shawcross. Courtesy the artist and Victoria Miro Gallery, London

A smaller scale exhibition opened on 10 June at Victoria Miro... London

...predominantly showcasing 'maquettes' such as these and confirming Conrad's appeal to the architectural field.

In April this year, Shawcross was moreover commissioned by the Southwark Council to create a large-scale installation in Dulwich Park. His design, 'Three Perpetual Chords,' refers to the mathematical patterns composing music, materialising melodious notes with thick, intertwined chunks of iron.

The multiple sculptures, working as 'visual descriptions of musical chords,' are disseminated across the park, interacting with the bypassers as well as symmetrically responding to each other.

These architectural forms are placed in random spots of the park, continually surprising visitors and provoking unexpected encounters.

Roughly human height, the sculptures exist as modulable forms adopting the shape visitors wish to see (a playground for children, a simple presence for joggers...)

Wallpaper* Newsletter

Receive our daily digest of inspiration, escapism and design stories from around the world direct to your inbox.

-

The Subaru Forester is the definition of unpretentious automotive design

The Subaru Forester is the definition of unpretentious automotive designIt’s not exactly king of the crossovers, but the Subaru Forester e-Boxer is reliable, practical and great for keeping a low profile

By Jonathan Bell

-

Sotheby’s is auctioning a rare Frank Lloyd Wright lamp – and it could fetch $5 million

Sotheby’s is auctioning a rare Frank Lloyd Wright lamp – and it could fetch $5 millionThe architect's ‘Double-Pedestal’ lamp, which was designed for the Dana House in 1903, is hitting the auction block 13 May at Sotheby's.

By Anna Solomon

-

Naoto Fukasawa sparks children’s imaginations with play sculptures

Naoto Fukasawa sparks children’s imaginations with play sculpturesThe Japanese designer creates an intuitive series of bold play sculptures, designed to spark children’s desire to play without thinking

By Danielle Demetriou

-

Celia Paul's colony of ghostly apparitions haunts Victoria Miro

Celia Paul's colony of ghostly apparitions haunts Victoria MiroEerie and elegiac new London exhibition ‘Celia Paul: Colony of Ghosts’ is on show at Victoria Miro until 17 April

By Hannah Hutchings-Georgiou

-

Conrad Shawcross plays with the dimensions of time for Royal Salute

Conrad Shawcross plays with the dimensions of time for Royal SaluteTime Chamber, a new work by Conrad Shawcross for Royal Salute, is the second edition in the brand’s Art of Wonder collection

By Henrietta Thompson

-

‘Darker, more sinister themes’: Paula Rego’s decade of self-discovery is the subject of a new London exhibition

‘Darker, more sinister themes’: Paula Rego’s decade of self-discovery is the subject of a new London exhibitionPaula Rego’s ‘Letting Loose’, at Victoria Miro in London, considers the artist’s work from the 1980s

By Hannah Silver

-

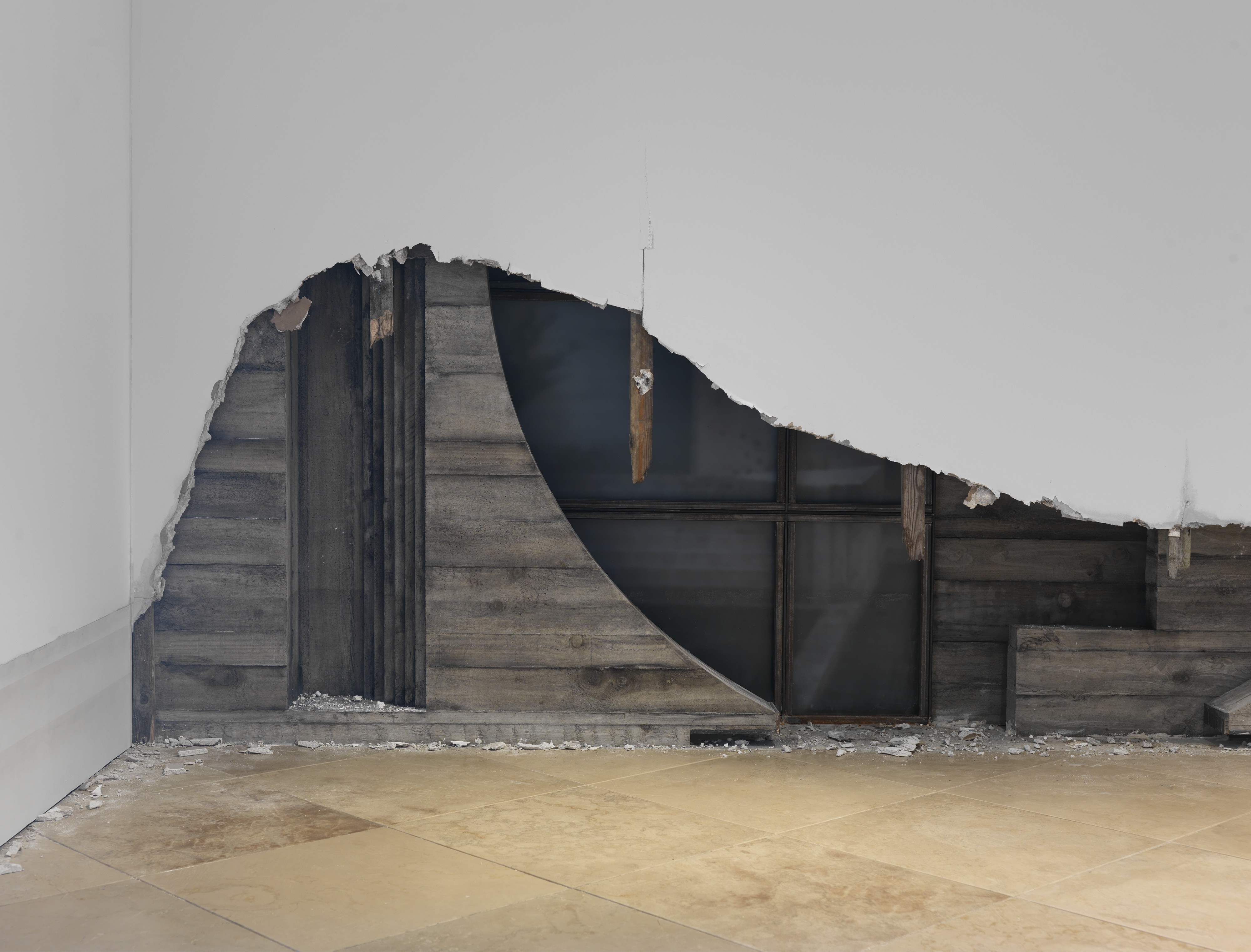

Alex Hartley’s eerie ode to Carlo Scarpa in Venice

Alex Hartley’s eerie ode to Carlo Scarpa in VeniceAlex Hartley’s theatrical new installation ‘Closer than Before’ at Victoria Miro Venice is a haunting take on architectural destruction in Venice

By Thea Hawlin

-

William Kentridge on failed utopias and transcending borders: ‘art must defend the uncertain’

William Kentridge on failed utopias and transcending borders: ‘art must defend the uncertain’Azu Nwagbogu profiles South African artist William Kentridge, whose show at London's Royal Academy of Arts runs until 11 December 2022

By Azu Nwagbogu

-

2022 Royal Academy Architecture Prize recognises Renée Gailhoustet

2022 Royal Academy Architecture Prize recognises Renée GailhoustetThe 2022 Royal Academy Architecture Prize is awarded to Renée Gailhoustet, with the shortlist for the 2022 Royal Academy Dorfman Award revealed at the same time

By Ellie Stathaki

-

Stan Douglas’ riff on alternative realities has us seeing double

Stan Douglas’ riff on alternative realities has us seeing doubleCoinciding with the announcement that the Vancouver artist will represent Canada in the 2021 Venice Biennale, his galleries in New York and London are staging a dual survey of his ambitious video installation Doppelgänger

By Jessica Klingelfuss

-

Singling out the solo booths to see at Frieze Los Angeles

Singling out the solo booths to see at Frieze Los AngelesOver 70 galleries will descend on Paramount Pictures Studio for the second edition of the West Coast art fair (14-16 February), anchored by an ambitious programme of special projects, film screenings, talks, and institutional collaborations

By Jessica Klingelfuss