Auto-destruct: Lucio Fontana at Tornabuoni Art

‘It’s an elegant space, and Lucio Fontana is an elegant artist,’ said the art critic Edward Lucie-Smith at this week's opening of Tornabuoni Art, the new Albemarle Street gallery devoted to post-war and Novecento Italian art.

Lucie-Smith sat downstairs, in a room punctured through at either end by white spiral staircases with brass balustrades. The undeniably elegant affair was hosted by gallerist Ursula Casamonti, whose brother Marco renovated the space after the departure of David Linley’s furniture boutique. For the first London showing of the Italian-Argentinian artist in a decade, Casamonti hung Fontana’s late-career canvases at generous intervals, giving her room to lift them off the wall and display the underside, to great effect.

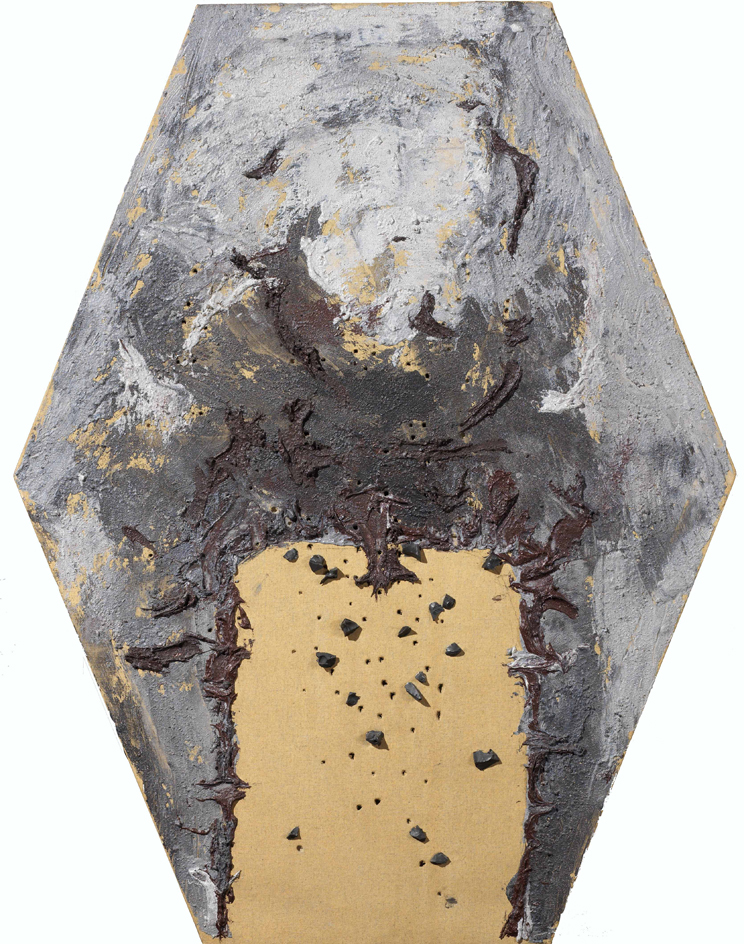

Yet underlying the elegance was a vaguely threatening feeling that you can’t escape in the presence of Fontana’s art. Most of the works here – spanning the period of 1955 until just before the artist’s death in 1968 – have been vigorously slashed through with knives, pierced with tools and even ripped by hand.

They come from a time when Fontana, formerly a sculptor in Milan and Paris, had largely abandoned the practice. After spending the Second World War in Buenos Aires, he returned to a Milan almost completely destroyed by the Allies. His wounded canvases reflect the city’s ruined treasures. In Lucie-Smith’s words, ‘He wanted to disturb with art that was apparently attacked.’

Fontana’s experimentation gave rise to the spatialist movement – a rebuttal of more controlled modernists like Mondrian. Spatialism strived for a new dimension in painting. And the suggestion of a 3D entity beneath the surface is the reason Fontana’s torn canvases are as interesting when pulled off the wall, allowing the light to penetrate the ruptures.

The artist never really abandoned sculpture in the end. He simply gave it a new form and direction. And while he was rebuilding his career in this new Italian avant garde, so was Italy rebuilding itself.

Gallerist Ursula Casamonti has hung Fontana’s late-career canvases at generous intervals, giving her room to lift them off the wall and display the undersides

Underlying the elegance is a vaguely threatening feeling that you can’t escape in the presence of Fontana’s art. Pictured: Concetto spaziale, 1956

Most of the works here – spanning the period of 1955 until just before the artist’s death in 1968 – have been vigorously slashed through with knives, pierced with tools and even ripped by hand. Pictured: Concetto spaziale, Attese, 1964.

His wounded canvases reflect Milan’s ruined treasures, desecrated during the Second World War. These wounds give the work an ominous, threatening aura. Pictured: Concetto spaziale, L'Inferno, 1956.

'He wanted to disturb with art that was apparently attacked,' explains art critic Edward Lucie-Smith. Pictured: Concetto spaziale, 1953

It was Fontana's experimentation that pathed the way for the spatialist movement; the suggestion of a 3D entity beneath the surface is the reason his torn canvases are as interesting when pulled off the wall. Pictured: Concetto spaziale, 1962

'Lucio Fontana' will be on show until 5 December

INFORMATION

'Lucio Fontana' is on view until 5 December

ADDRESS

Tornabuoni Art

46 Albemarle Street

London, W1S 1JN

Wallpaper* Newsletter

Receive our daily digest of inspiration, escapism and design stories from around the world direct to your inbox.

Based in London, Ellen Himelfarb travels widely for her reports on architecture and design. Her words appear in The Times, The Telegraph, The World of Interiors, and The Globe and Mail in her native Canada. She has worked with Wallpaper* since 2006.

-

All-In is the Paris-based label making full-force fashion for main character dressing

All-In is the Paris-based label making full-force fashion for main character dressingPart of our monthly Uprising series, Wallpaper* meets Benjamin Barron and Bror August Vestbø of All-In, the LVMH Prize-nominated label which bases its collections on a riotous cast of characters – real and imagined

By Orla Brennan

-

Maserati joins forces with Giorgetti for a turbo-charged relationship

Maserati joins forces with Giorgetti for a turbo-charged relationshipAnnouncing their marriage during Milan Design Week, the brands unveiled a collection, a car and a long term commitment

By Hugo Macdonald

-

Through an innovative new training program, Poltrona Frau aims to safeguard Italian craft

Through an innovative new training program, Poltrona Frau aims to safeguard Italian craftThe heritage furniture manufacturer is training a new generation of leather artisans

By Cristina Kiran Piotti