Lucy Williams exhibition at Timothy Taylor Gallery, London

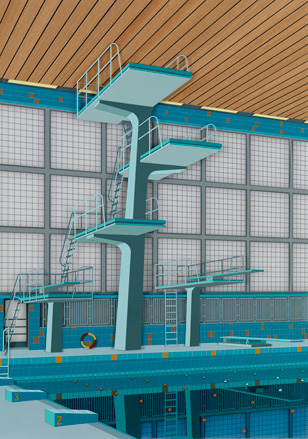

If you are new to midcentury architecture, you might look upon a cache of Modernist snapshots as a far-gone utopia, an optimistic framework for communal living and prosperity built by the Greatest Generation - without all the baggage accumulated in the darker years between then and now.

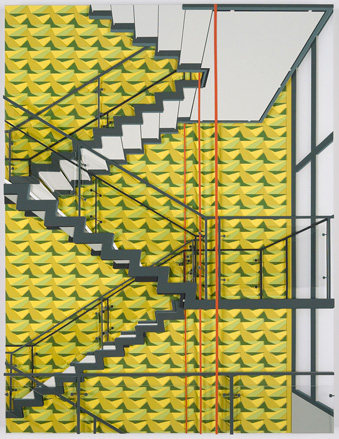

This is how London artist Lucy Williams comes to her subject matter, residential tours de force by celebrated Modernists like Walter Gropius, Marcel Breuer and Brinkman en van dern Vlugt, the architects who built the Sonneveld House in Rotterdam. In capturing the houses in their midcentury prime, she lends them a happy retro quality, punctuated with Technicolor zips and patterns.

As a result, her second solo exhibition 'Pavilion', 16 vast new works debuting this week at Timothy Taylor Gallery, expresses a sort of anti-Edward Hopper innocence that is only half the story.

Beneath the façades are layers of collage that Williams carfully applies to affect a true structure to her art. Transforming builders' salvage into scale balsa wood panels, steel strips, cork tiles, Plexiglas windows and bricks of real mortar, she assembles architectural bas-relief which increases in depth the closer they are.

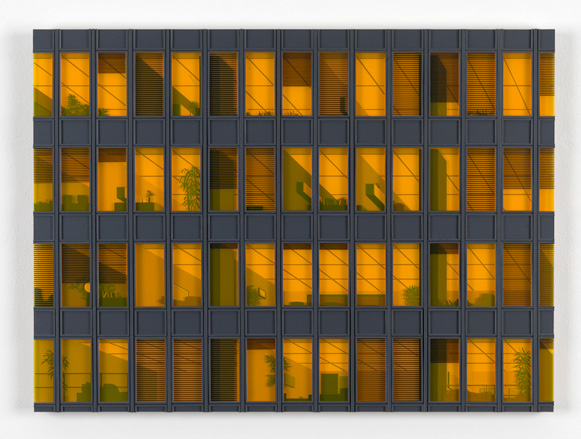

The 3m, mural-like 'Montparnasse', based on a photograph of Jean Dubuisson's Maine-Montparnasse apartment complex, is an intricate latticework for which Williams hand-cut thousands of coloured paper fragments beneath a duck-egg sky. Her homage to the Brutalist block is more sanguine and infinitely more involved than, say, Andreas Gursky's iconic photograph of the 1990s.

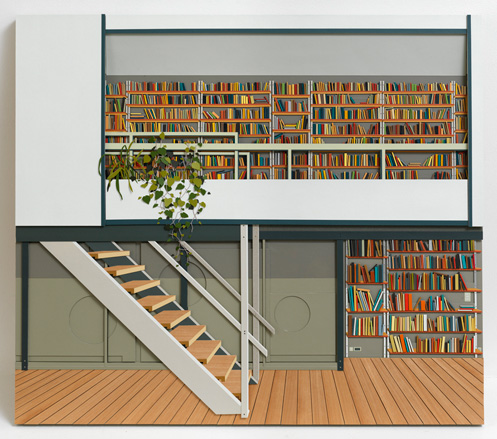

Her rendition of the library at the Maison de Verre in Paris, designed by Pierre Chareau, sits in stark contrast to the dim, dusty library lore that emerged in the 1970s and 1980s. These books, you are confident, will be read, savoured, enjoyed.

Other works have intense skies fabricated from woven tapestries or cross-stitch.

Williams' attention to detail is second only to those architects who pioneered the Modernist movement. Their stories are absent here, as are the stories behind the families who occupied these spaces, however optimistically or pessimistically. In some works the shades are drawn or the views inside obscured, suggesting something even deeper within, reluctant to come to the surface.

Williams has softened these references by rendering the grid structure in soft wood with peg-board inserts, reminiscent of children's furniture

'Seagram Building', 2012

'The Tiled Cathedral', 2012

'Continental Interior', 2012

'The Sonneveld House', 2012

'Herrick Court', 2012

'Nieuwe Bowen (North Elevation)', 2011

'Parkleys', 2011

'City Hall', 2011

ADDRESS

Timothy Taylor Gallery

15 Carlos Place

London W1K 2EX

Wallpaper* Newsletter

Receive our daily digest of inspiration, escapism and design stories from around the world direct to your inbox.

Based in London, Ellen Himelfarb travels widely for her reports on architecture and design. Her words appear in The Times, The Telegraph, The World of Interiors, and The Globe and Mail in her native Canada. She has worked with Wallpaper* since 2006.

-

Marylebone restaurant Nina turns up the volume on Italian dining

Marylebone restaurant Nina turns up the volume on Italian diningAt Nina, don’t expect a view of the Amalfi Coast. Do expect pasta, leopard print and industrial chic

By Sofia de la Cruz

-

Tour the wonderful homes of ‘Casa Mexicana’, an ode to residential architecture in Mexico

Tour the wonderful homes of ‘Casa Mexicana’, an ode to residential architecture in Mexico‘Casa Mexicana’ is a new book celebrating the country’s residential architecture, highlighting its influence across the world

By Ellie Stathaki

-

Jonathan Anderson is heading to Dior Men

Jonathan Anderson is heading to Dior MenAfter months of speculation, it has been confirmed this morning that Jonathan Anderson, who left Loewe earlier this year, is the successor to Kim Jones at Dior Men

By Jack Moss

-

National Portrait Gallery unveils new brand identity and programme ahead of 2023 reopening

National Portrait Gallery unveils new brand identity and programme ahead of 2023 reopeningLondon’s National Portrait Gallery has revealed its new branding and full 2023-2024 programming information ahead of its much-anticipated June 2023 reopening

By Harriet Lloyd-Smith

-

Gathering: the new Soho gallery blending art and social activism

Gathering: the new Soho gallery blending art and social activismGathering, the newest gallery resident in London’s Soho, will focus on contemporary art exploring systemic social issues. Ahead of Tai Shani’s inaugural show, we speak to founders Alex Flick and Trinidad Fombella about their vision for the gallery

By Harriet Lloyd-Smith

-

Emma Talbot explores Greek myth and femininity at Whitechapel Gallery

Emma Talbot explores Greek myth and femininity at Whitechapel GalleryIn ‘The Age/L’Età’, her Max Mara Art Prize show at Whitechapel Gallery, Emma Talbot imagines a reality where violence is overturned by resolution, nurtured by an elderly female protagonist

By Martha Elliott

-

Cornelia Parker’s major Tate Britain survey explores British fragility

Cornelia Parker’s major Tate Britain survey explores British fragilityAt Tate Britain, Cornelia Parker’s first London survey show dissects politics and history and reframes everyday life

By Martha Elliott

-

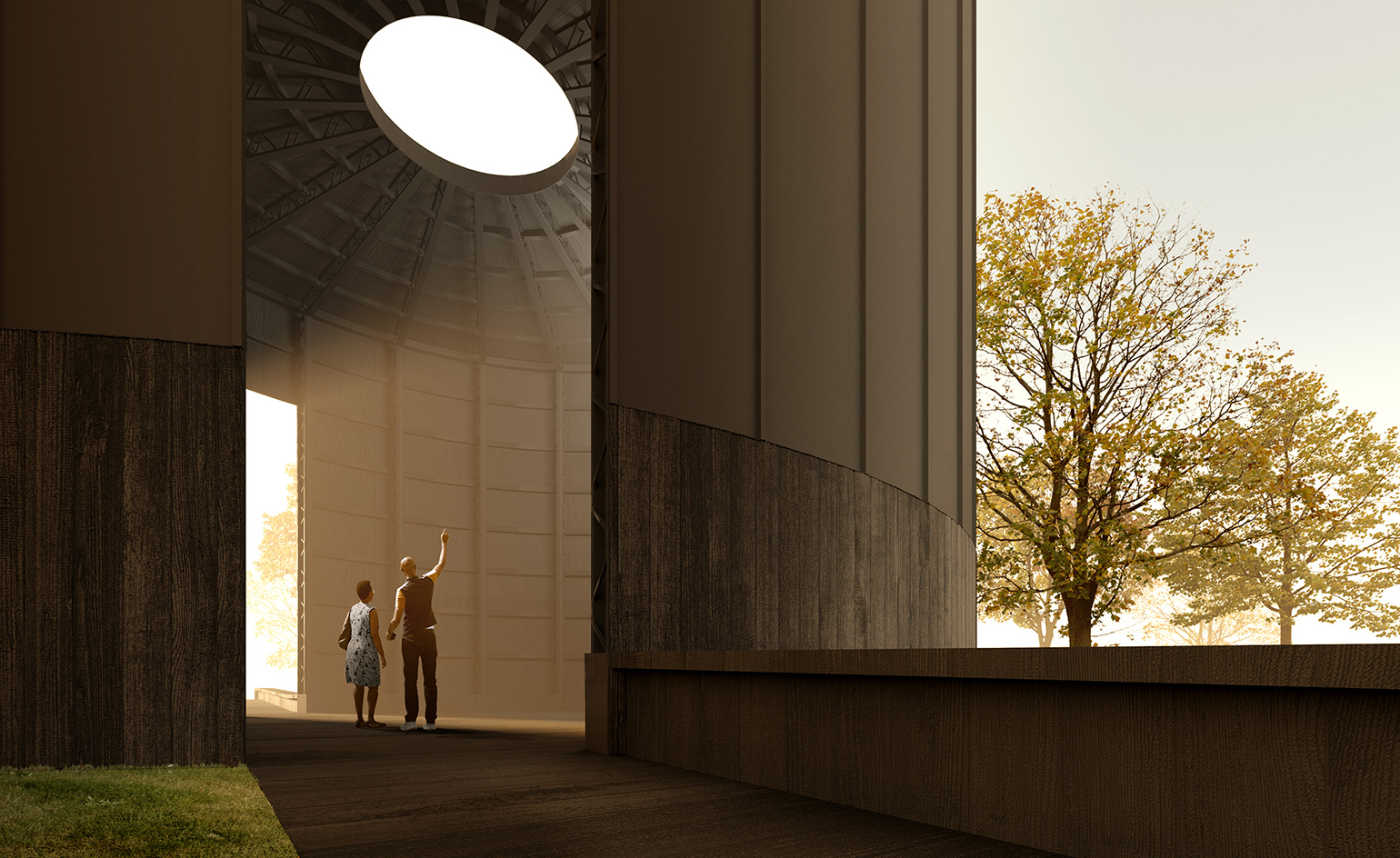

Theaster Gates’ design for Serpentine Pavilion 2022 revealed

Theaster Gates’ design for Serpentine Pavilion 2022 revealedThe American artist and urban planner reveals his plans for the Serpentine Pavilion 2022. Black Chapel has spirituality, music and community at its heart

By TF Chan

-

Courtauld Gallery gears up for November reopening following modernisation

Courtauld Gallery gears up for November reopening following modernisationLondon's Courtauld Gallery at Somerset House is set for November reopening following extensive modernisation by architecture studio Witherford Watson Mann

By Ellie Stathaki

-

Carmody Groarke revives Victorian vaulted space for Manchester museum

Carmody Groarke revives Victorian vaulted space for Manchester museumArchitects Carmody Groarke revive a vast, brick space for the flexible new Special Exhibitions Gallery at the Science and Industry Museum in Manchester

By Ellie Stathaki

-

Grove Square Galleries makes a bold entrance on London's art scene

Grove Square Galleries makes a bold entrance on London's art sceneLaunching during Frieze Week with a show by artist Christopher Kieling, new gallery Grove Square Galleries is dynamic, collaborative and forward-looking

By Jessica Klingelfuss