Sex, wit and cigars: five contemporary artists on Marcel Duchamp

After 60 years out of print, the seminal 1959 monograph Marcel Duchamp is back in circulation courtesy of Hauser & Wirth Publishers. To mark the occasion, we asked five contemporary artists – Ed Ruscha, Gillian Wearing, Larry Bell, Monica Bonvicini and Mika Rottenberg – what Duchamp means to them

Marcel Duchamp means different things to different people. To some, he fathered the readymade, to others, he turned the role of the artist on its head. To Willem de Kooning in 1951, he was a ‘one-man movement’.

Published in 1959, the book Marcel Duchamp soon became the bible of the artist’s work. It was the result of years of Duchamp’s collaboration with its author, art historian and critic Robert Lebel, and offered a comprehensive and penetrating study of the artist: from his early painting, subsequent farewell to painting, and invention of the readymade to his fixation on the fetish, a subject explored in a show at Thaddaeus Ropac. Witty, sensual, absurd, ‘Please Touch’ (curated by Paul B. Franklin and now on view at the gallery’s Paris Marais space) emphasises how, through Duchamp’s lens, and with the right, or wrong, state of mind, almost any conceivable object could be a fetish.

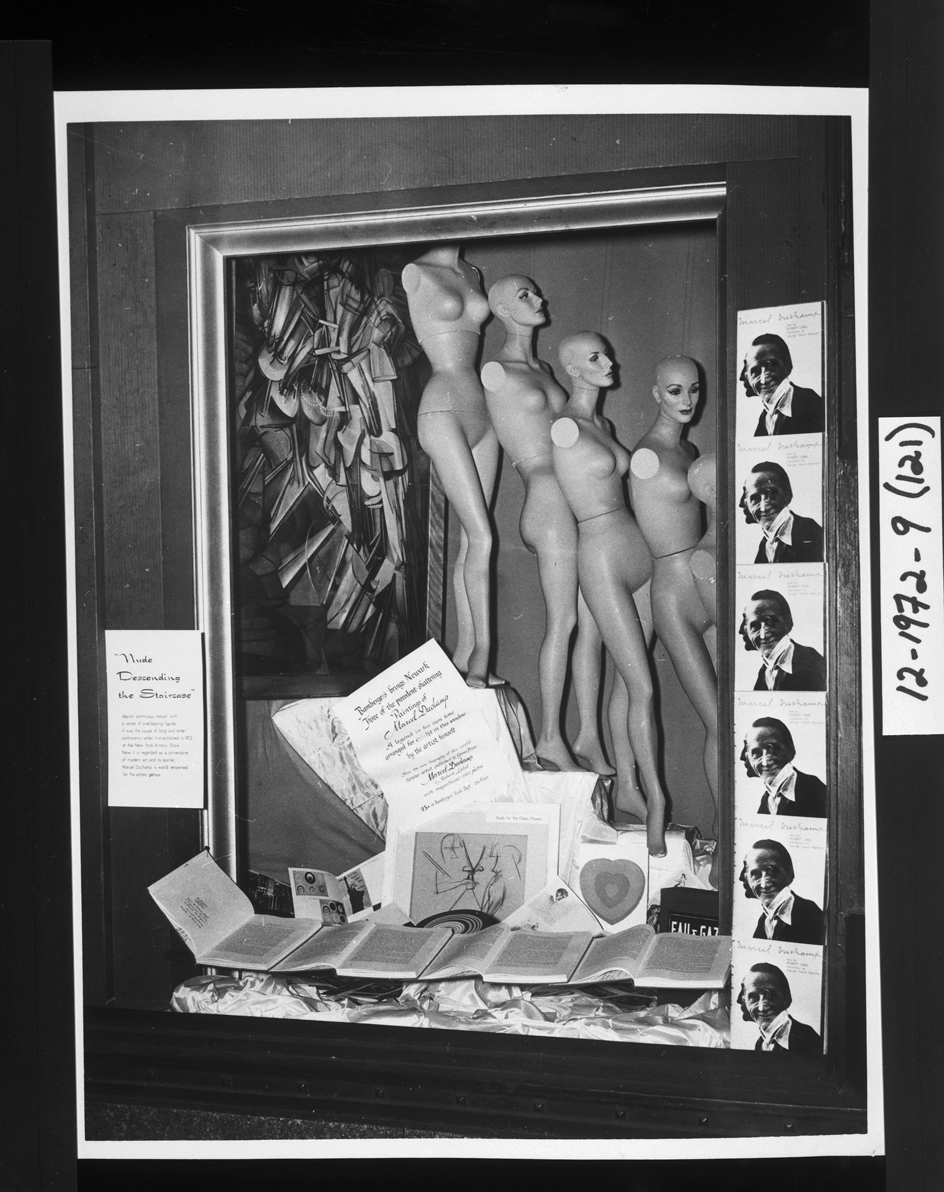

Window display designed by Duchamp to publicise the original book, L. Bamberger and Co., Market and Washington Streets, Newark, New Jersey, January 29 – February 1, 1959. Photography: Handy-Boesser Photographers. Philadelphia Museum of Art Archives, Alexina and Marcel Duchamp Papers, series XII, subseries A, box 32, folder 3

Marcel Duchamp went out of print for 60 years, but the Grove Press English edition is now back in circulation with Hauser & Wirth Publishers’ authorised facsimile of Duchamp’s first monograph and catalogue raisonné, brought back to life with Jean-Jacques Lebel (Robert Lebel’s son) and Association Marcel Duchamp. To this day, the book’s texts, which include chapters written by Duchamp, HP Roché, and André Breton, remain uncannily contemporary, as does Duchamp’s own book design.

Marcel Duchamp in the words of five leading contemporary artists

To mark the occasion, we gathered the thoughts of five contemporary artists who have directly, or indirectly, cited Marcel Duchamp in their work. From an appreciation of the artist’s non-exclusive relationships with media to a first-hand anecdote about the way he held his cigar, this is what they had to say:

Ed Ruscha

‘When Duchamp came along in the early part of the last century, he hit upon things that were profound and sublime. It was as though he had discovered or invented a completely new musical instrument.’

Gillian Wearing

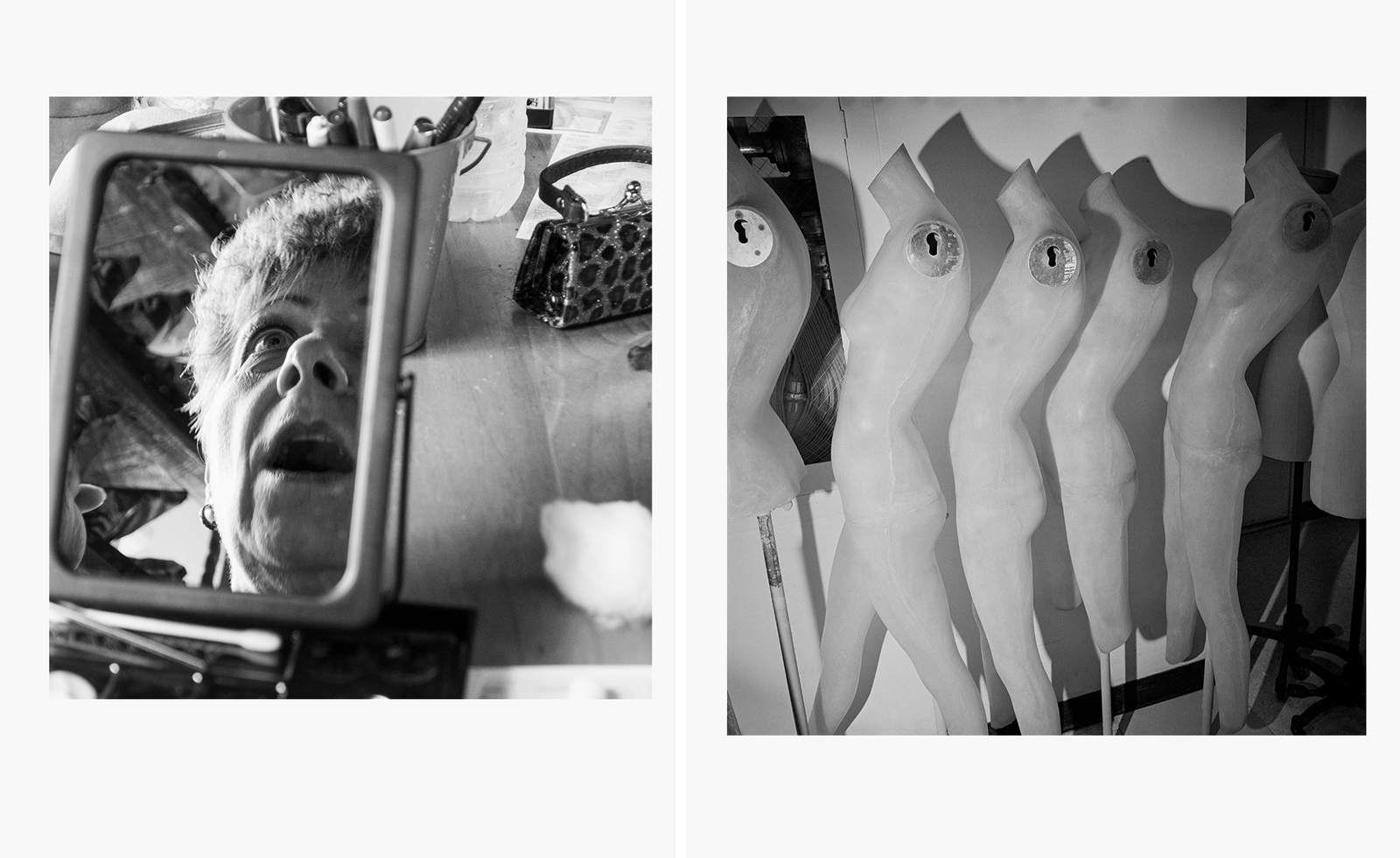

‘Duchamp made me realise you do not have to be faithful to any one medium, you can embrace them all. More radically, you didn't have to make work with traditional mediums, art could be made from anything or could have been made already (found objects), then recontextualised. More personally, his shapeshifting photographs had an impact on me; one where he appeared as a much older version of himself via a trick of a light bulb, and others where he became his alter ego, Rrose Sélavy. The latter inspired me to become both Duchamp and Duchamp as a woman in my photographic work Me and Madame and Monsieur Duchamp, which added further layers to his disguise.’

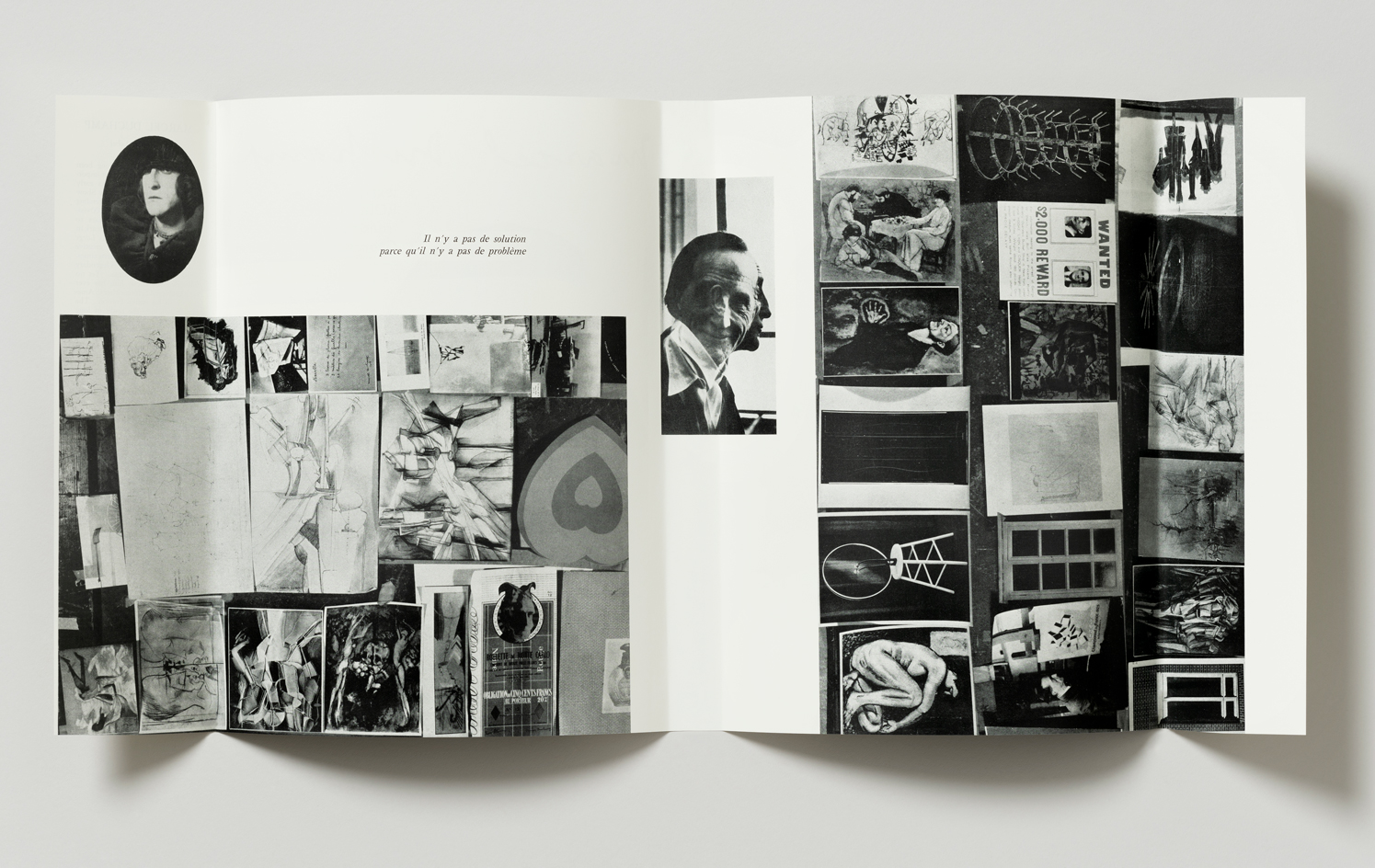

Spread from Hauser & Wirth Publishers’ 2021 facsimile of Marcel Duchamp, the artist’s 1959 monograph. Artwork by Marcel Duchamp © Association Marcel Duchamp / ProLitteris, Zurich, 2021.

Larry Bell

‘My memories of Duchamp are brief. He came to my studio in 1962 with English artist Richard Hamilton and American surrealist William Copley. They had come to Los Angeles to look at where Marcel was going to have his first retrospective [the Pasadena Museum of Art]. The museum director was Walter Hopps, who was previously my dealer.

Wallpaper* Newsletter

Receive our daily digest of inspiration, escapism and design stories from around the world direct to your inbox.

‘These three guys descended on my studio and gently knocked on the door. I wasn’t expecting anyone to come, and none of my friends would ever come to the front door, so these were unknown intruders. I had a little peephole at the front and I saw these guys dressed in neckties and suits. I was positive they were city inspectors. During that time, there was a lot of pressure on people who lived in storefronts; it wasn’t legal. This was my studio, but I lived there also.

‘They knocked for about 20 minutes. I finally opened the door and before I could say hello, one of the guys said “Walter Hopps sent us”, so I let them in. At that point, I had very bad hearing, and I didn't hear the names, apart from Copley who introduced me to the group. I thought they might be collectors, and showed them around. One of them had an English accent. The older guy didn't say much, but he smoked a cigar. I smoked cigars too, but I’d never seen anyone hold a cigar between his little finger and ring finger before. The English guy was explaining to the older fella what I was doing, and it was not correct, so I tried to correct the older guy’s understanding. Then Copley said something like, “Marcel, didn’t you do something like this a long time ago?” When he said Marcel, I realised who the older guy was, and I fucking freaked. I couldn’t talk anymore. I was totally catatonic and threw myself against the wall. All of a sudden the atmosphere had changed. They thanked me for letting them come, and they left. On your question about influence, I tried to hold the cigar as Duchamp did, but it didn’t work for me.’

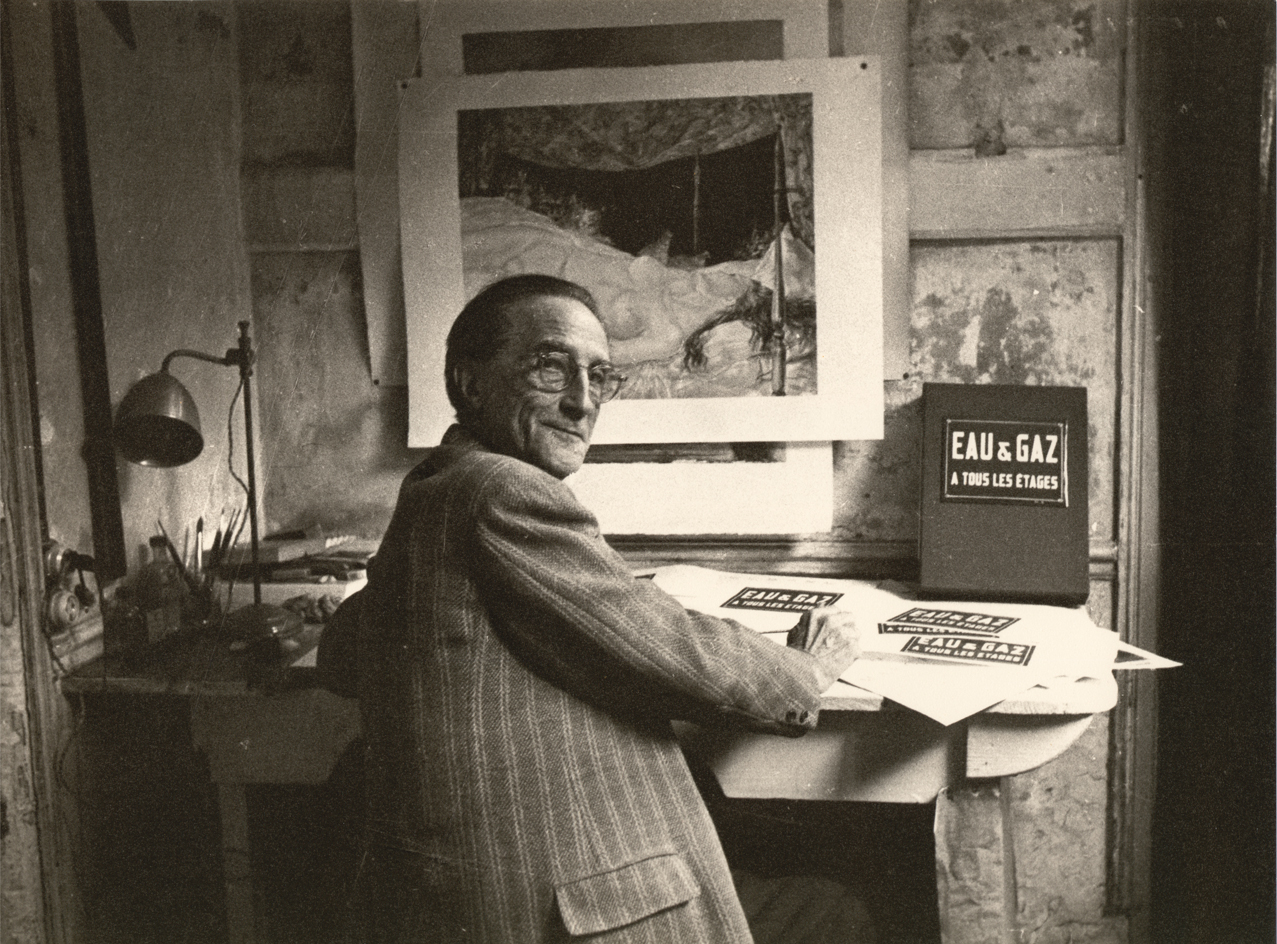

Duchamp signing the labels EAU & GAZ À TOUS LES ÉTAGES for the deluxe edition of Sur Marcel Duchamp (the title of the orginal French version of the book) at the Trianon Press offices, Paris, 23 September 1958. Photography: Richard Lusby. Courtesy Marcel Duchamp Archives, Paris

Monica Bonvicini

‘Duchamp's use of unusual materials, as well as his choice of productions, is such a fetish, expressing a male desire typical for someone coming from his background. His desire to escape classification of any sort made his own art and his own persona ungraspable, turning himself into fetish subjects. I always found his dealing with erotica and sex not only beautiful but funny and irreverent as no male artist of his generation did.’

Mika Rottenberg

‘[Duchamp is] a huge influence [in] his seriously playful approach to art as a game of logic constructs and values. [Also] his titles, and the way he made viewers complete and participate in the work with no pretence.’

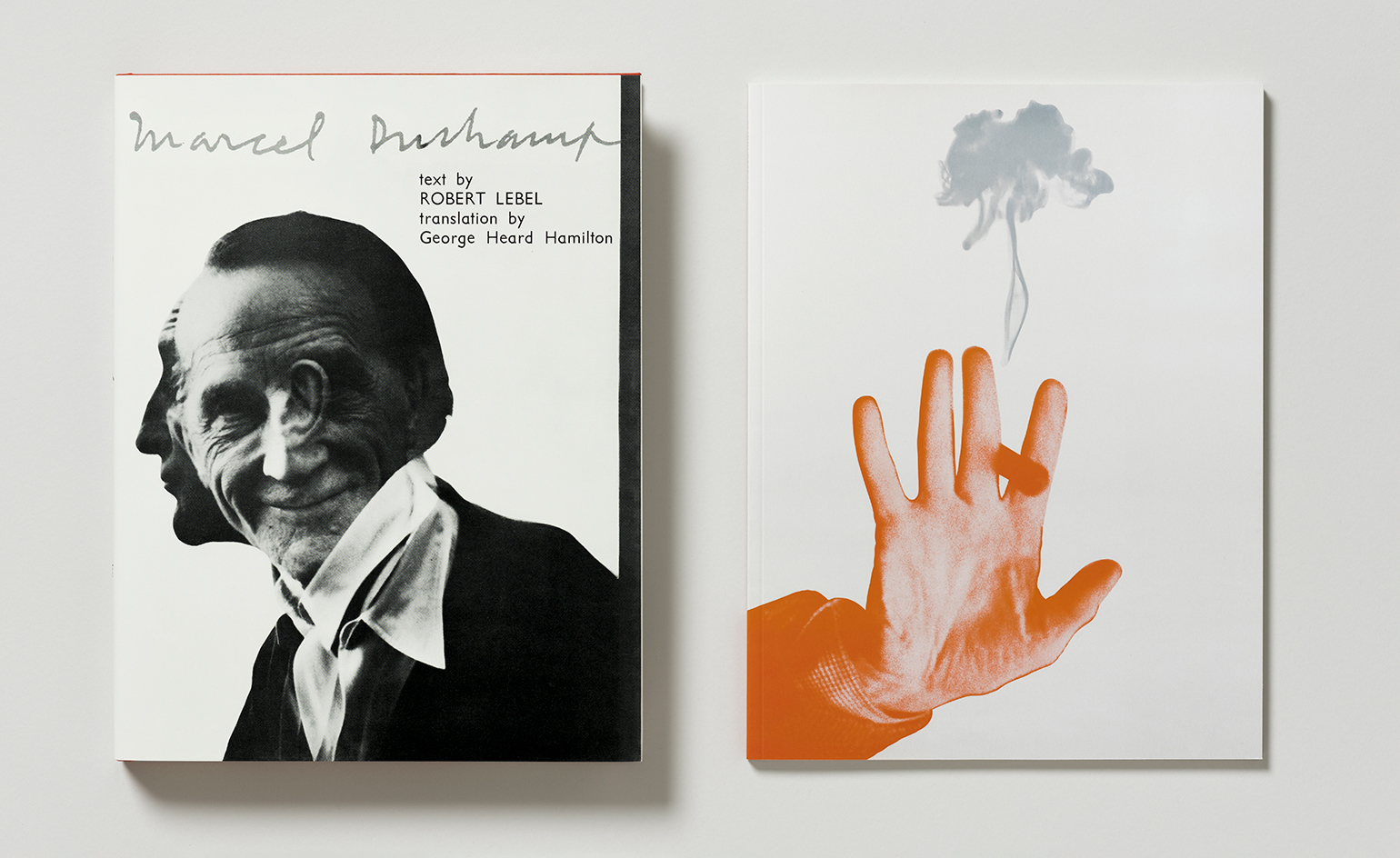

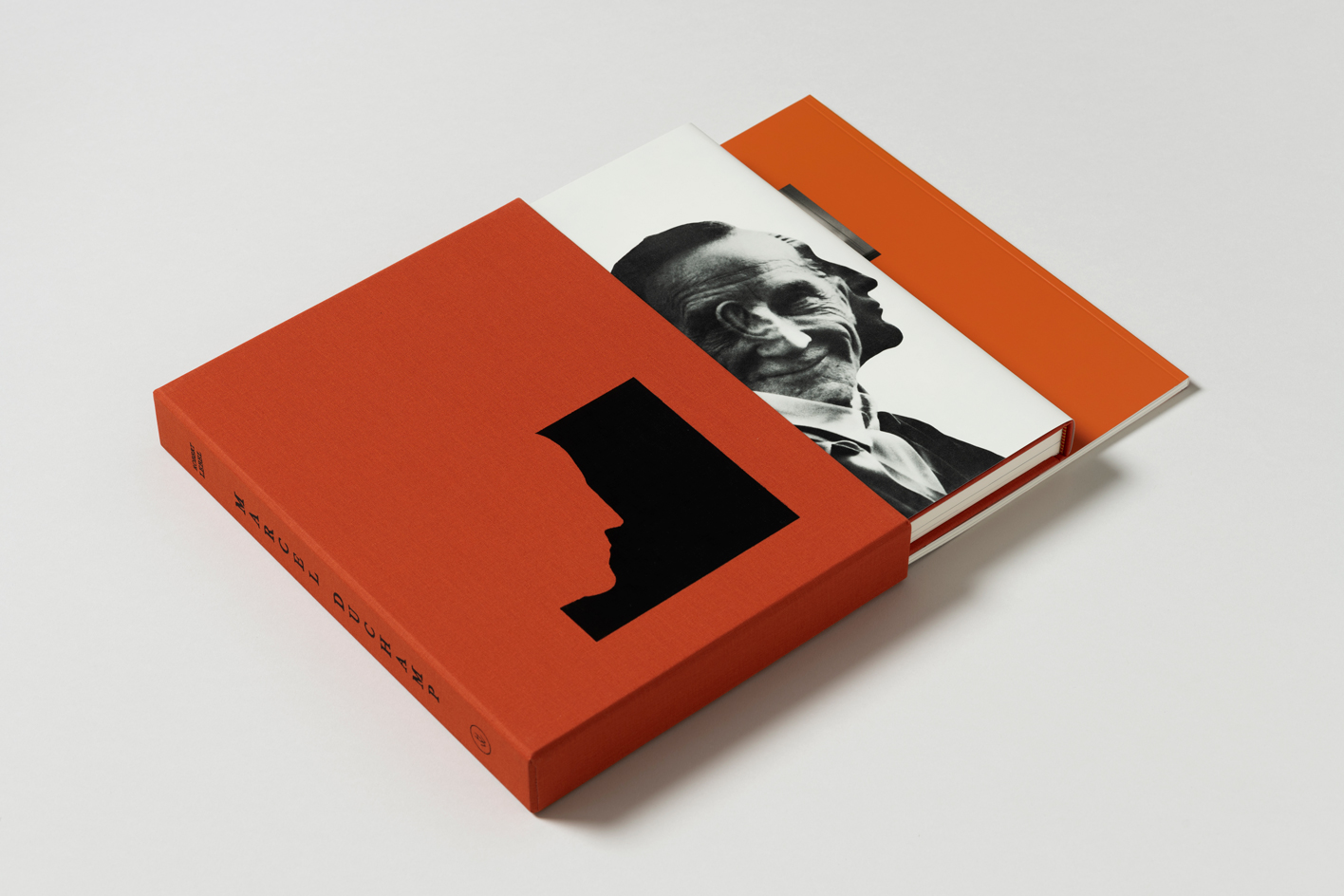

The book with slipcase. Artwork by Marcel Duchamp © Association Marcel Duchamp / ProLitteris, Zurich, 2021.

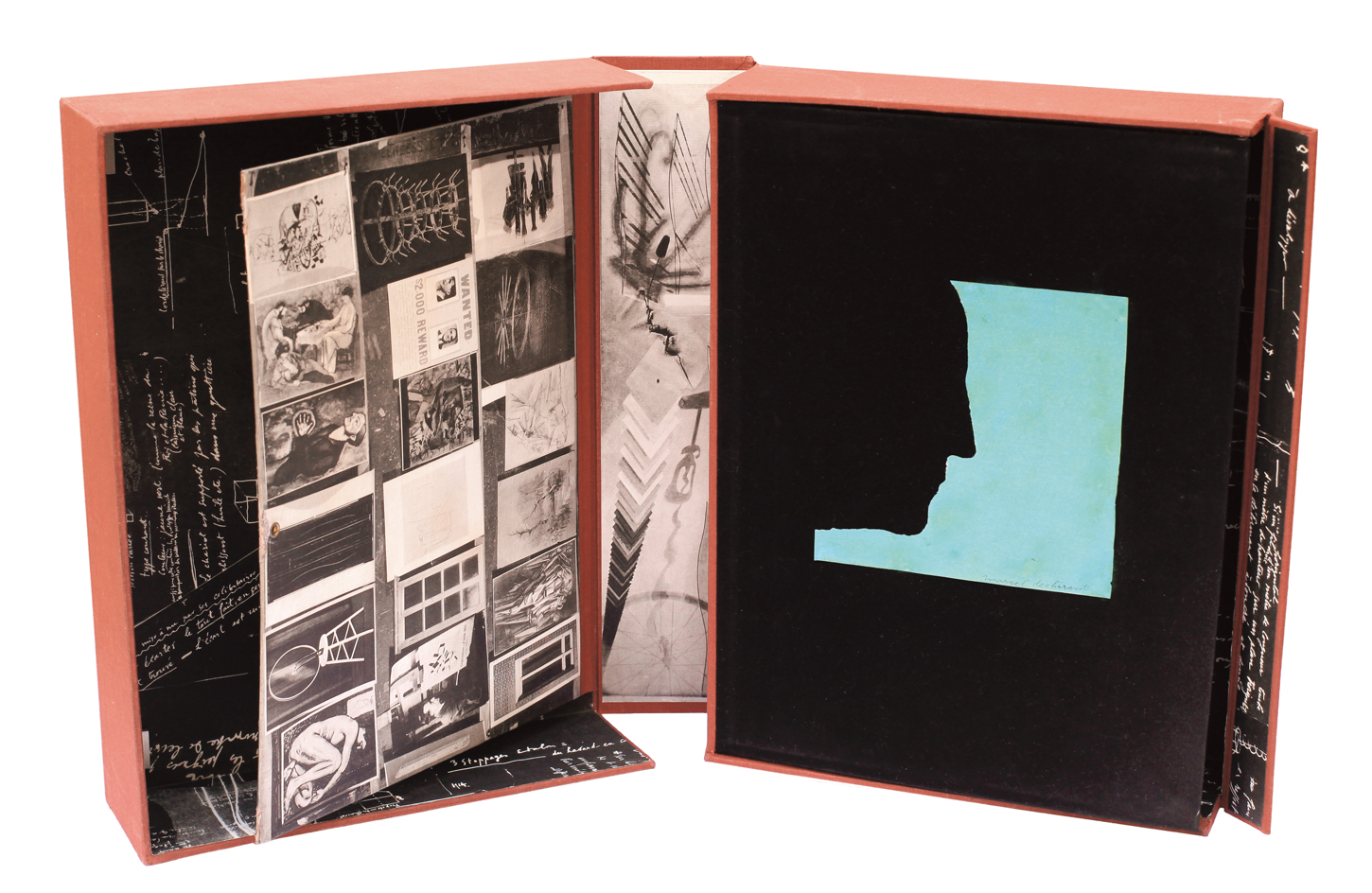

A 1959 deluxe edition, press copy. Galerie 1900 – 2000 Artwork by Marcel Duchamp © Association Marcel Duchamp / ProLitteris, Zurich, 2021.

INFORMATION

Marcel Duchamp, £100, Hauser & Wirth Publishers. shop.hauserwirth.com

‘Please Touch: Marcel Duchamp and the Fetish', until 29 January 2022, Thaddaeus Ropac, Paris Marais. ropac.net

Harriet Lloyd-Smith was the Arts Editor of Wallpaper*, responsible for the art pages across digital and print, including profiles, exhibition reviews, and contemporary art collaborations. She started at Wallpaper* in 2017 and has written for leading contemporary art publications, auction houses and arts charities, and lectured on review writing and art journalism. When she’s not writing about art, she’s making her own.

-

Put these emerging artists on your radar

Put these emerging artists on your radarThis crop of six new talents is poised to shake up the art world. Get to know them now

By Tianna Williams

-

Dining at Pyrá feels like a Mediterranean kiss on both cheeks

Dining at Pyrá feels like a Mediterranean kiss on both cheeksDesigned by House of Dré, this Lonsdale Road addition dishes up an enticing fusion of Greek and Spanish cooking

By Sofia de la Cruz

-

Creased, crumpled: S/S 2025 menswear is about clothes that have ‘lived a life’

Creased, crumpled: S/S 2025 menswear is about clothes that have ‘lived a life’The S/S 2025 menswear collections see designers embrace the creased and the crumpled, conjuring a mood of laidback languor that ran through the season – captured here by photographer Steve Harnacke and stylist Nicola Neri for Wallpaper*

By Jack Moss

-

‘Dressed to Impress’ captures the vivid world of everyday fashion in the 1950s and 1960s

‘Dressed to Impress’ captures the vivid world of everyday fashion in the 1950s and 1960sA new photography book from The Anonymous Project showcases its subjects when they’re dressed for best, posing for events and celebrations unknown

By Jonathan Bell

-

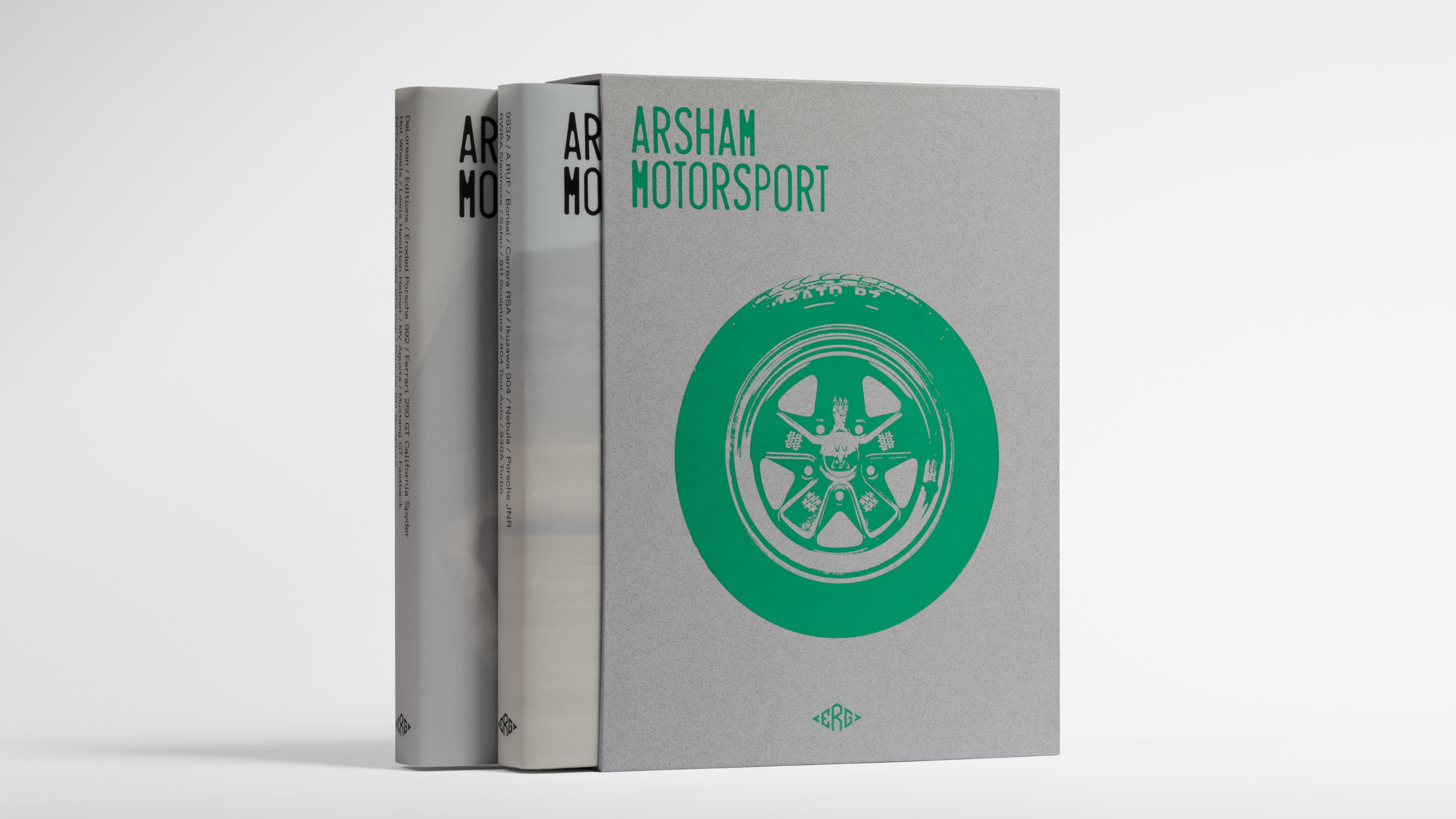

Daniel Arsham’s new monograph collates the works of the auto-obsessed American artist

Daniel Arsham’s new monograph collates the works of the auto-obsessed American artist‘Arsham Motorsport’ is two volumes of inspiration, process and work, charting artist Daniel Arsham’s oeuvre inspired by the icons and forms of the automotive industry

By Jonathan Bell

-

Era-defining photographer David Bailey guides us through the 1980s in a new tome not short of shoulder pads and lycra

Era-defining photographer David Bailey guides us through the 1980s in a new tome not short of shoulder pads and lycraFrom Yves Saint Laurent to Princess Diana, London photographer David Bailey dives into his 1980s archive in a new book by Taschen

By Tianna Williams

-

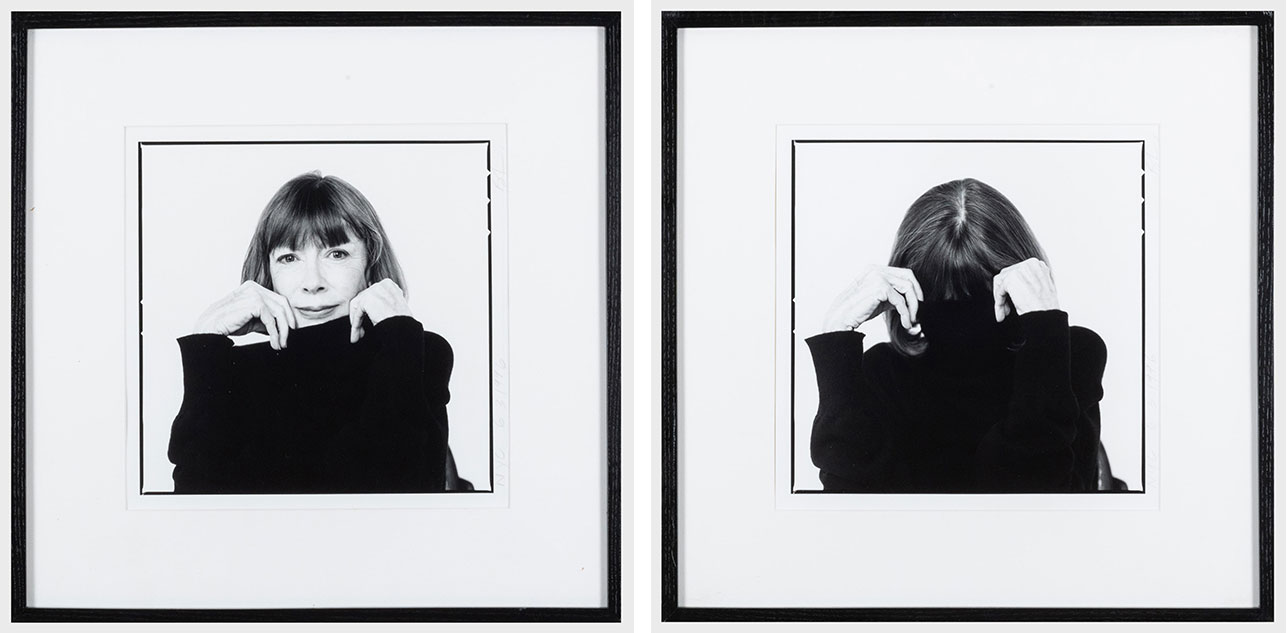

Inside Joan Didion’s unseen diary of personal relationships and post-therapy notes

Inside Joan Didion’s unseen diary of personal relationships and post-therapy notesA newly discovered diary by Joan Didion is soon to be published. Titled 'Notes to John', the journal documents her relationship with her daughter, husband, alcoholism, and depression

By Tianna Williams

-

Carsten Höller’s new Book of Games: 336 playful pastimes for the bold and the bored

Carsten Höller’s new Book of Games: 336 playful pastimes for the bold and the boredArtist Carsten Höller invites readers to step out of their comfort zone with a series of subversive games

By Anne Soward

-

Distracting decadence: how Silvio Berlusconi’s legacy shaped Italian TV

Distracting decadence: how Silvio Berlusconi’s legacy shaped Italian TVStefano De Luigi's monograph Televisiva examines how Berlusconi’s empire reshaped Italian TV, and subsequently infiltrated the premiership

By Zoe Whitfield

-

Inside the distorted world of artist George Rouy

Inside the distorted world of artist George RouyFrequently drawing comparisons with Francis Bacon, painter George Rouy is gaining peer points for his use of classic techniques to distort the human form

By Hannah Silver

-

How a sprawling new book honours the legacy of cult photographer Larry Fink

How a sprawling new book honours the legacy of cult photographer Larry Fink‘Larry Fink: Hands On / A Passionate Life of Looking’ pays homage to an American master. ‘He had this ability to connect,’ says publisher Daniel Power

By Jordan Bassett