Masahisa Fukase and the sorrow of lost love, solitude and death

Masahisa Fukase’s sorrow seeps through his later photographs like a poison: painful, suffocating, and all consuming. For eight years, the Japanese photographer obsessively captured ravens in his native Hokkaido, vainly seeking an antidote to the venom of a failed marriage.

His second wife and muse Yōko left him in 1976, and a mournful Fukase careened into a crippling depression. Drinking heavily, the photographer found refuge in the birds that flocked around his local train station. Published in 1986, the photobook Ravens (or Karasu) was born from his heartbreak. Now, a rare collection of prints from this seminal series has been unveiled in a new exhibition opening this week at Michael Hoppen Gallery in London.

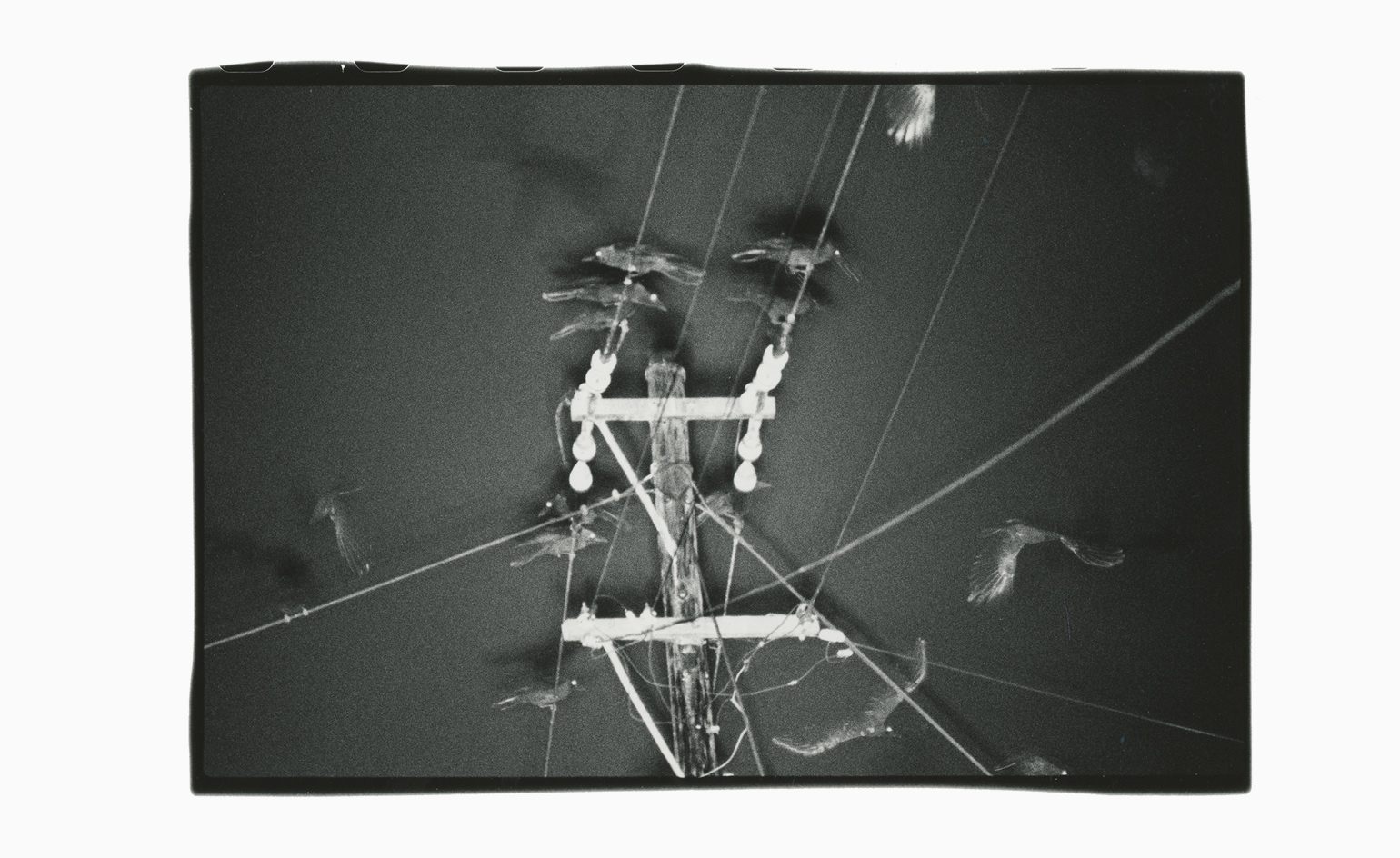

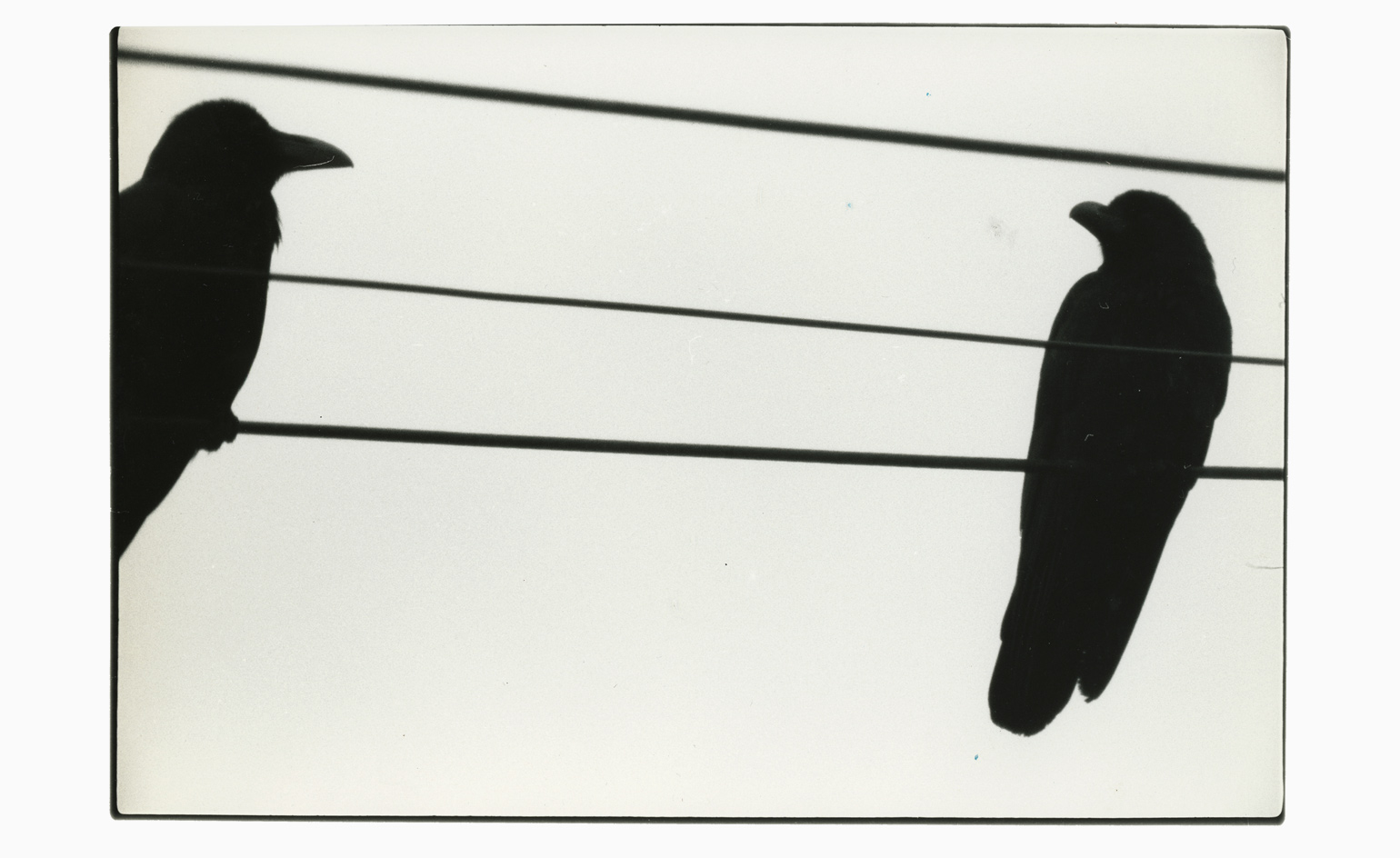

The grainy, monochromatic images make for compelling viewing. Ravens are considered ominous creatures in Japan and Fukase’s pictures are stained with a uneasy sense of misadventure. His portentous ravens are occasionally interjected with other subjects – the swollen underbelly of a passing aeroplane, for one – but they feel no less ill fated.

In one of the show’s most powerful photographs, the gnashing jaws of a garbage truck are captured mid-fury; rubbish trails across the sky with the same violence as a battlefield explosion. The image is an enigma much like Fukase, who seems to have captured it from inside the mouth of the beast-like vehicle.

The exhibition is a rare chance to see works printed by Fukase himself – a show with this many master prints is unusual. It offers a faint bond to the photographer, whose melancholy makes him seem otherwise unattainable.

It took six years to convince Fukase’s family to consent to the exhibition, explains gallery owner Michael Hoppen of the undertaking. ‘It’s a strange life, but an extraordinary body of work,’ he says of Ravens. ‘This project is bigger than us, it’s bigger than the gallery.’

The London gallery has also loaned prints from Fukase’s Bukubuku – a self-portrait series shot in his bathtub – to the Tate Modern for its show, ‘Peforming for the Camera’. Hoppen explains: ‘Bukubuku is all about him. They’re auto-portraits, or rather, auto-emotional portraits, because he found it very easy to express himself through his photographs.’ Like in Ravens, he seems a man possessed by an inescapable grief.

Ravens has previously been called the best photobook of the last 25 years, drawing universal acclaim from photography critics and Fukase’s peers alike. ‘He had legions and legions of followers,’ says Hoppen. ‘Certainly with him there’s tremendous reverence and fondness not only to this man but also to this body of work. It’s a shining beacon to many [photographers].’

Fukase was never able to escape the harbingers of misfortune he orbited so closely during Ravens, even though he eventually remarried. He had spent over half a decade circling the fringes of death and decay with his camera, before finally relinquishing the project in 1982 and declaring that he had ‘become a raven’. In 1992, he fell down the stairs of his favourite Tokyo haunt and spent the next – and final – 20 years of his life in a coma. The ravens had come to claim him at last.

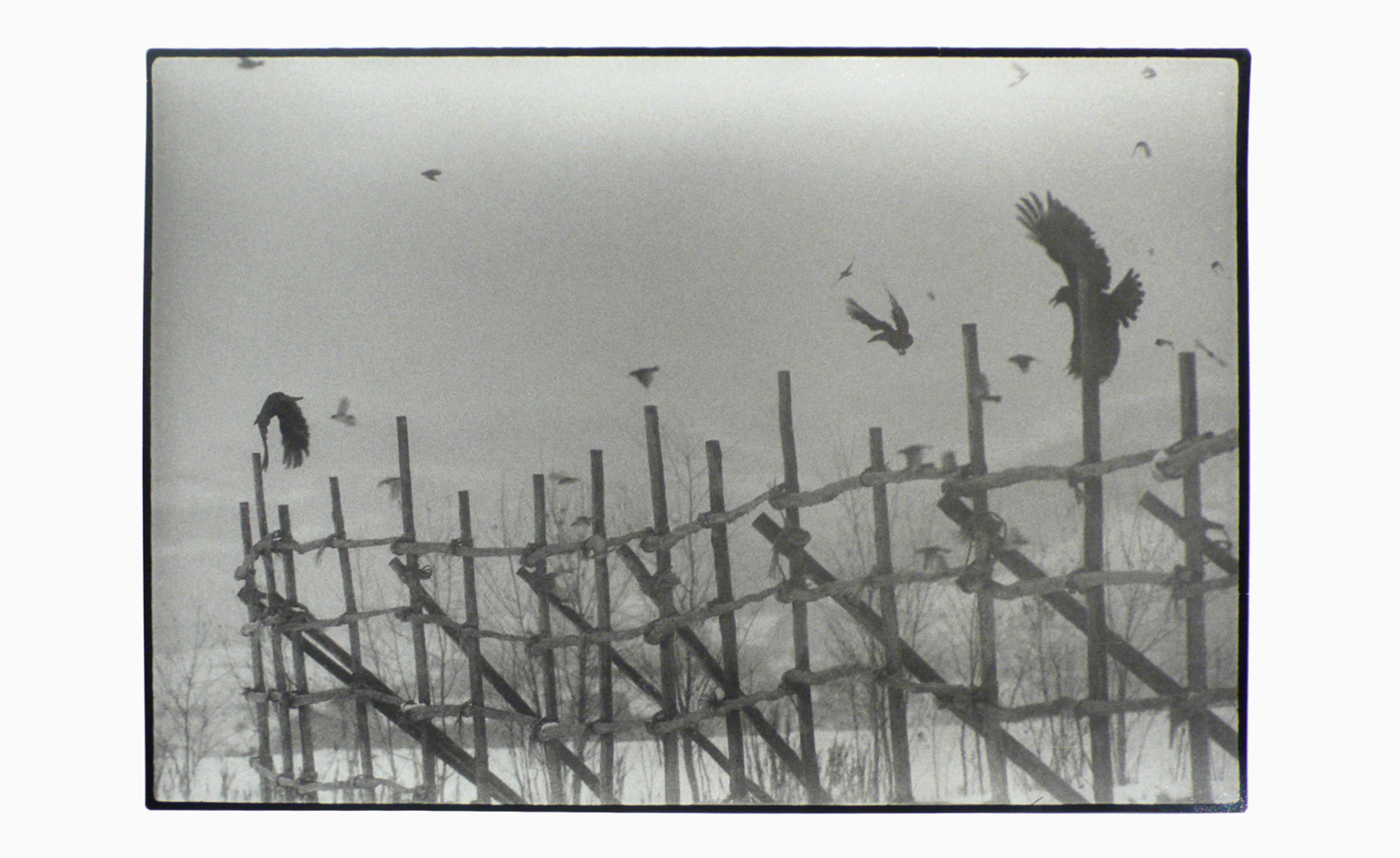

Fukase obsessively photographed ravens for six years in his native Hokkaido. Pictured: Nayoro, 1977

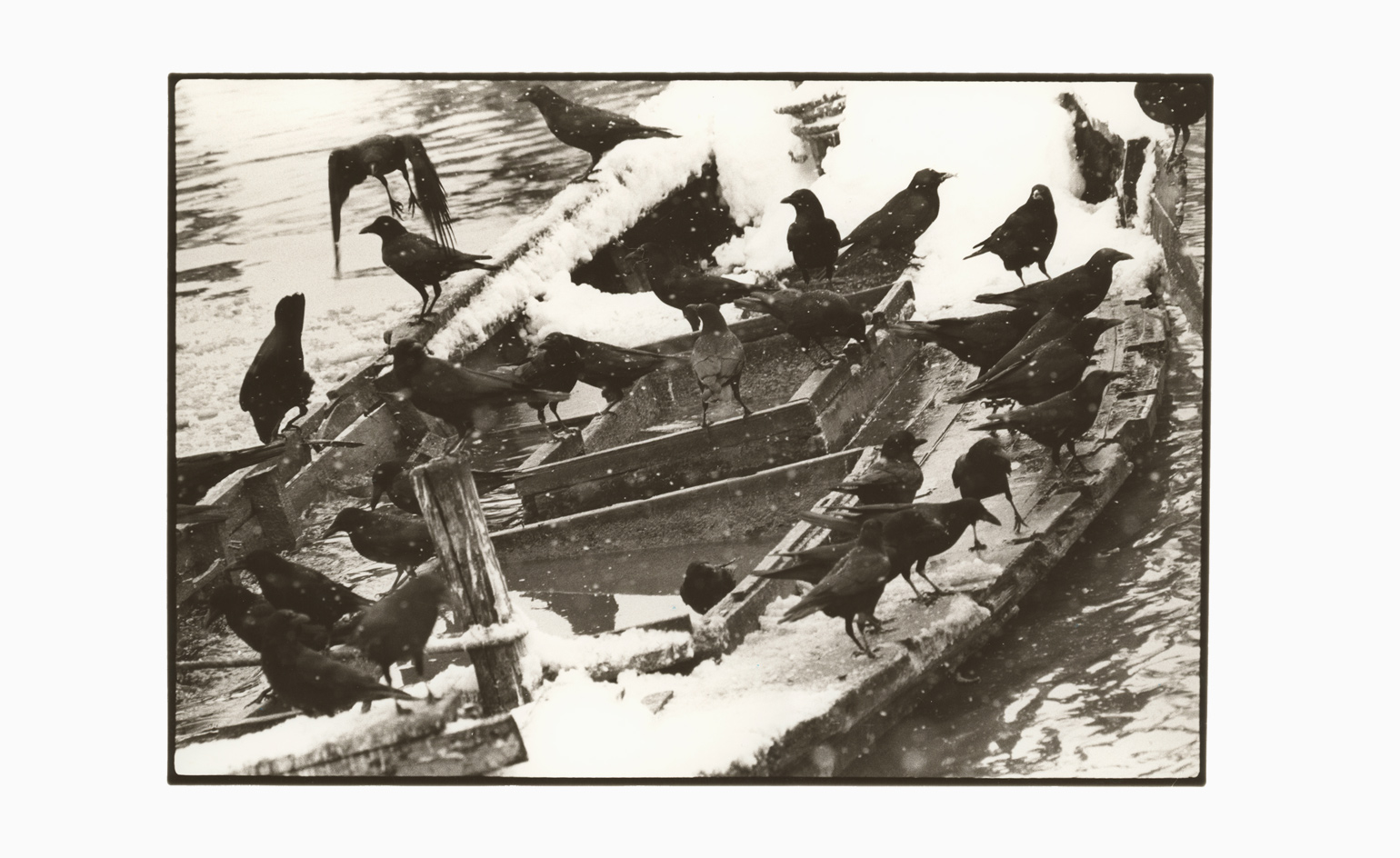

Published in 1986, it is regarded as one of the most important and accomplished bodies of work in photography. Pictured: Kanazawa, 1977

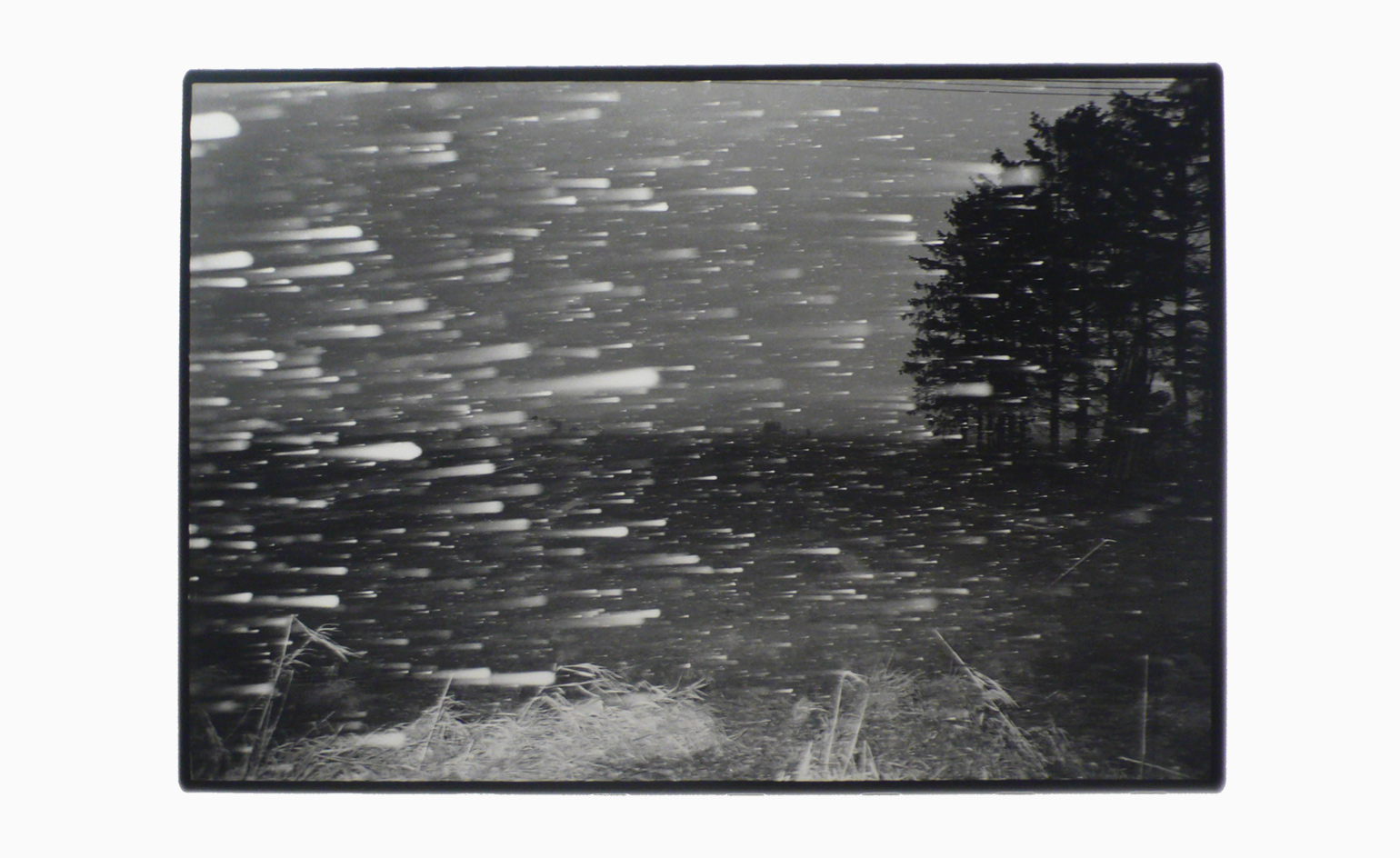

His portentous ravens are occasionally interjected with other subjects, such as heavy snowfall in Kanazawa, 1968

Fukase’s pictures are stained with a uneasy sense of misadventure. Pictured: Otaru, 1975

The grainy, monochromatic images make for compelling viewing. Pictured: Seikan Ferryboat, 1976

Untitled, 1976-1985

Ravens are considered ominous creatures in Japan. Pictured: Nayoro, 1977

INFORMATION

‘The Solitude of Ravens’ is on view until 23 April. For more information, visit Michael Hoppen Gallery’s website

Images © Masahisa Fukase Archives. Courtesy of Michael Hoppen Gallery

ADDRESS

3 Jubilee Place

London SW3 3TD

Wallpaper* Newsletter

Receive our daily digest of inspiration, escapism and design stories from around the world direct to your inbox.

-

Marylebone restaurant Nina turns up the volume on Italian dining

Marylebone restaurant Nina turns up the volume on Italian diningAt Nina, don’t expect a view of the Amalfi Coast. Do expect pasta, leopard print and industrial chic

By Sofia de la Cruz

-

Tour the wonderful homes of ‘Casa Mexicana’, an ode to residential architecture in Mexico

Tour the wonderful homes of ‘Casa Mexicana’, an ode to residential architecture in Mexico‘Casa Mexicana’ is a new book celebrating the country’s residential architecture, highlighting its influence across the world

By Ellie Stathaki

-

Jonathan Anderson is heading to Dior Men

Jonathan Anderson is heading to Dior MenAfter months of speculation, it has been confirmed this morning that Jonathan Anderson, who left Loewe earlier this year, is the successor to Kim Jones at Dior Men

By Jack Moss

-

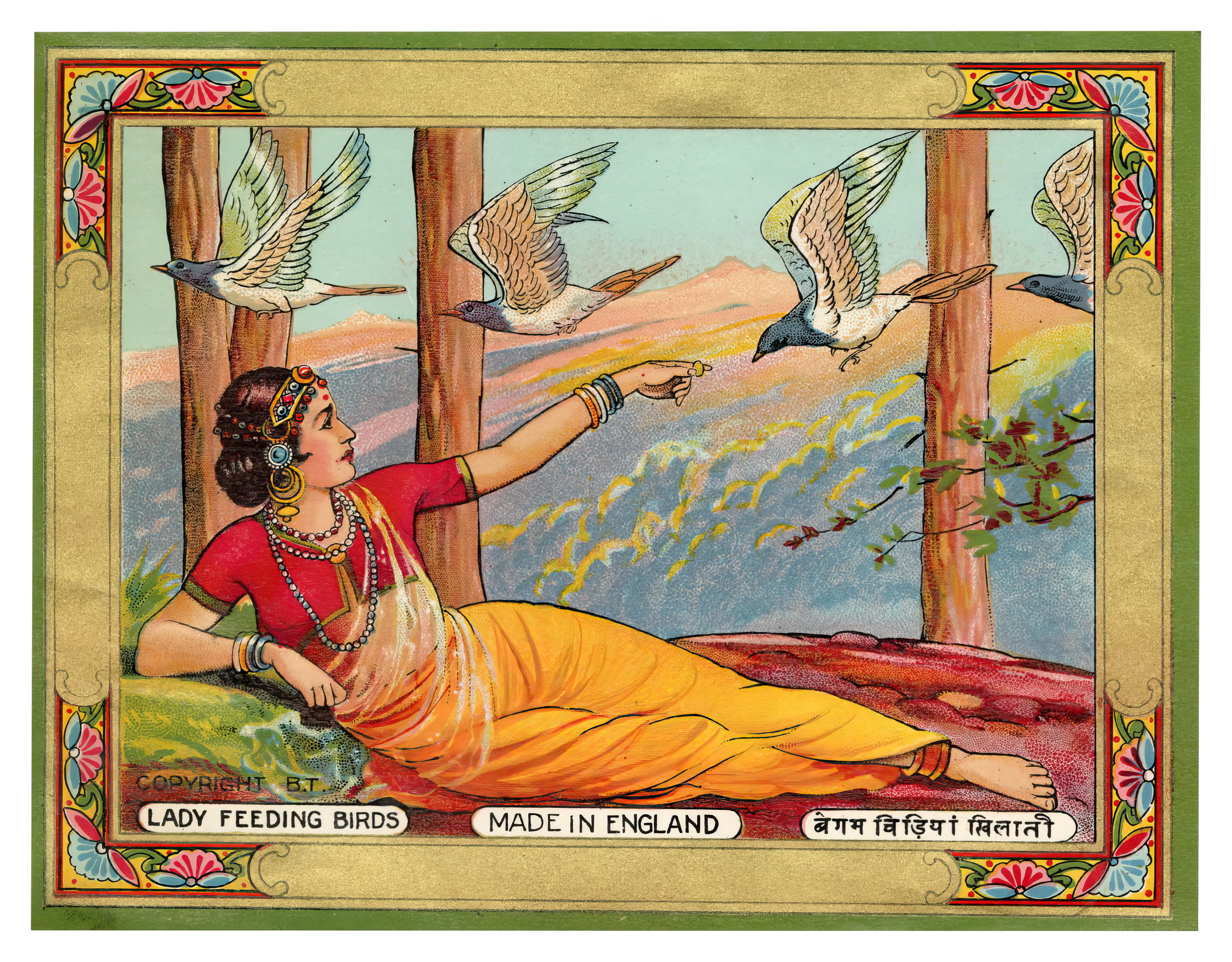

The art of the textile label: how British mill-made cloth sold itself to Indian buyers

The art of the textile label: how British mill-made cloth sold itself to Indian buyersAn exhibition of Indo-British textile labels at the Museum of Art & Photography (MAP) in Bengaluru is a journey through colonial desire and the design of mass persuasion

By Aastha D

-

Artist Qualeasha Wood explores the digital glitch to weave stories of the Black female experience

Artist Qualeasha Wood explores the digital glitch to weave stories of the Black female experienceIn ‘Malware’, her new London exhibition at Pippy Houldsworth Gallery, the American artist’s tapestries, tuftings and videos delve into the world of internet malfunction

By Hannah Silver

-

Ed Atkins confronts death at Tate Britain

Ed Atkins confronts death at Tate BritainIn his new London exhibition, the artist prods at the limits of existence through digital and physical works, including a film starring Toby Jones

By Emily Steer

-

Tom Wesselmann’s 'Up Close' and the anatomy of desire

Tom Wesselmann’s 'Up Close' and the anatomy of desireIn a new exhibition currently on show at Almine Rech in London, Tom Wesselmann challenges the limits of figurative painting

By Sam Moore

-

A major Frida Kahlo exhibition is coming to the Tate Modern next year

A major Frida Kahlo exhibition is coming to the Tate Modern next yearTate’s 2026 programme includes 'Frida: The Making of an Icon', which will trace the professional and personal life of countercultural figurehead Frida Kahlo

By Anna Solomon

-

A portrait of the artist: Sotheby’s puts Grayson Perry in the spotlight

A portrait of the artist: Sotheby’s puts Grayson Perry in the spotlightFor more than a decade, photographer Richard Ansett has made Grayson Perry his muse. Now Sotheby’s is staging a selling exhibition of their work

By Hannah Silver

-

From counter-culture to Northern Soul, these photos chart an intimate history of working-class Britain

From counter-culture to Northern Soul, these photos chart an intimate history of working-class Britain‘After the End of History: British Working Class Photography 1989 – 2024’ is at Edinburgh gallery Stills

By Tianna Williams

-

Celia Paul's colony of ghostly apparitions haunts Victoria Miro

Celia Paul's colony of ghostly apparitions haunts Victoria MiroEerie and elegiac new London exhibition ‘Celia Paul: Colony of Ghosts’ is on show at Victoria Miro until 17 April

By Hannah Hutchings-Georgiou