Meet Tyler Hobbs, the breakout star of generative art

Tyler Hobbs is making waves with abstract, algorithm-assisted art that harnesses code as a creative medium. We speak to the American artist ahead of two physical exhibitions in New York and London

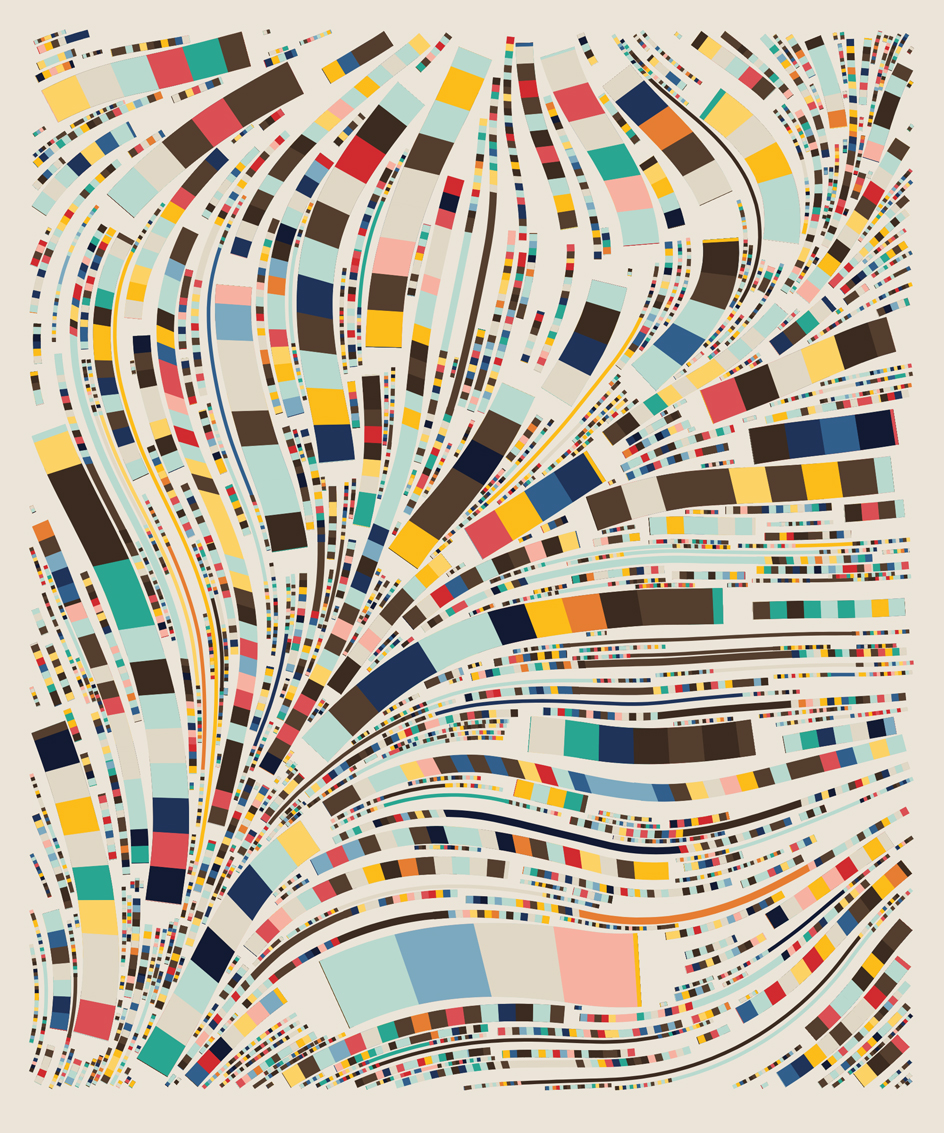

Tyler Hobbs is arguably the poster boy of generative art and the most eloquent champion of code as a creative medium. A former software engineer with a side passion for (figurative) drawing and painting, he discovered the potential of abstract, algorithm-assisted art a decade ago and began writing relatively simple programs that could create multiple variants on a theme. Running, tweaking and repeatedly re-running these programs, Hobbs has developed a uniquely ‘painterly’ digital aesthetic rooted in non-digital 'system' art and Abstract Expressionism.

Now 35, Hobbs is perhaps best known for the 2021 Fidenza series of 999 NFTs generated by a single algorithm. Just one Fidenza NFT sold for $3.3m, with critics charging hype and hysteria. Hobbs, though, has managed to do what few NFT-producing generative artists have: separate artistic speculation from crypto speculation. He has emerged from the rubble of the crypto collapse with a reputation undimmed and demand for his work as feverish as ever. And as attention shifts away from collectible cartoons and toward generative art of genuine value, the space has opened up for the form’s first credible, breakout star. Hobbs is claiming that space.

Tyler Hobbs to show in London and New York

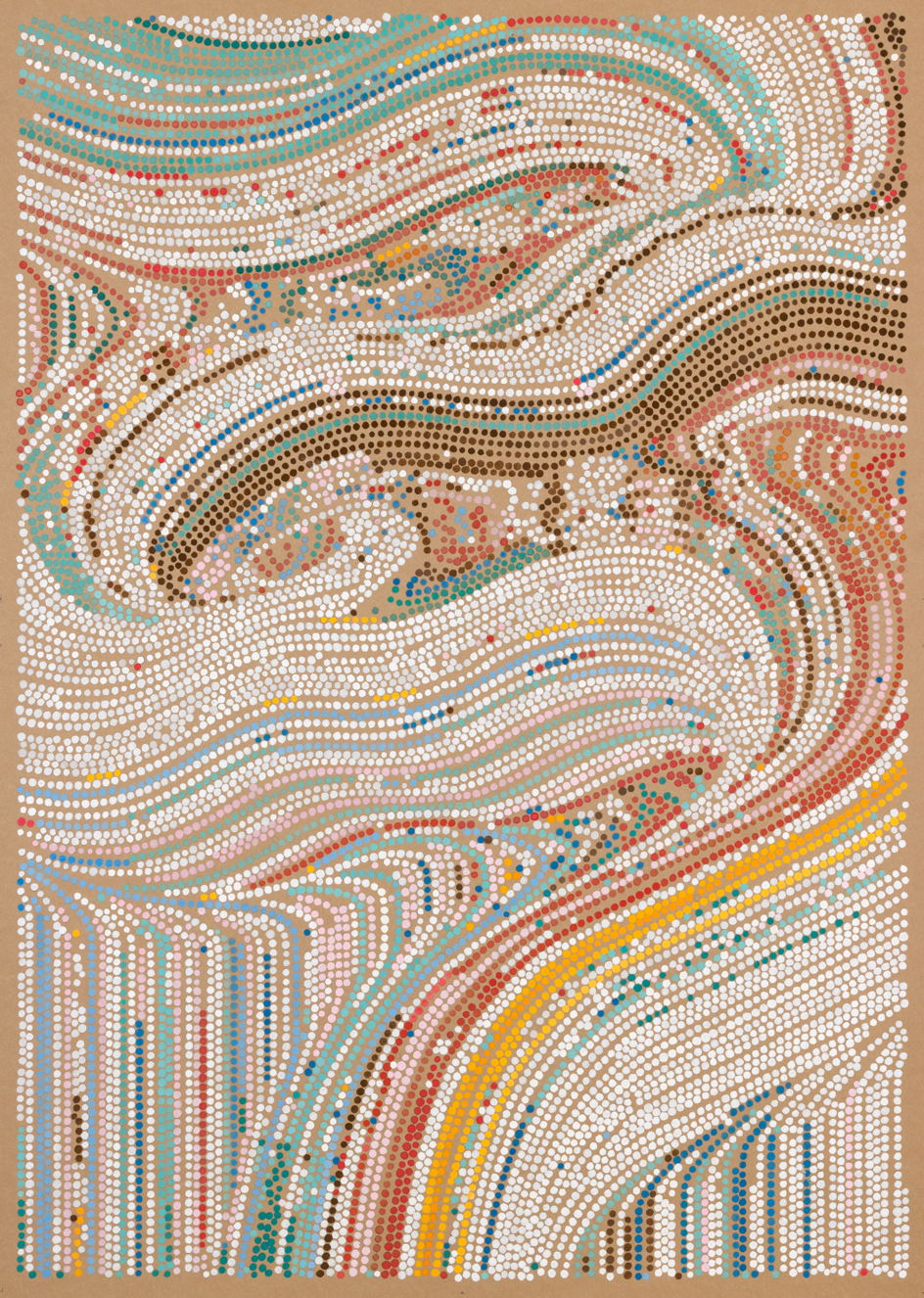

Tyler Hobbs, Fidenza #313, 2021

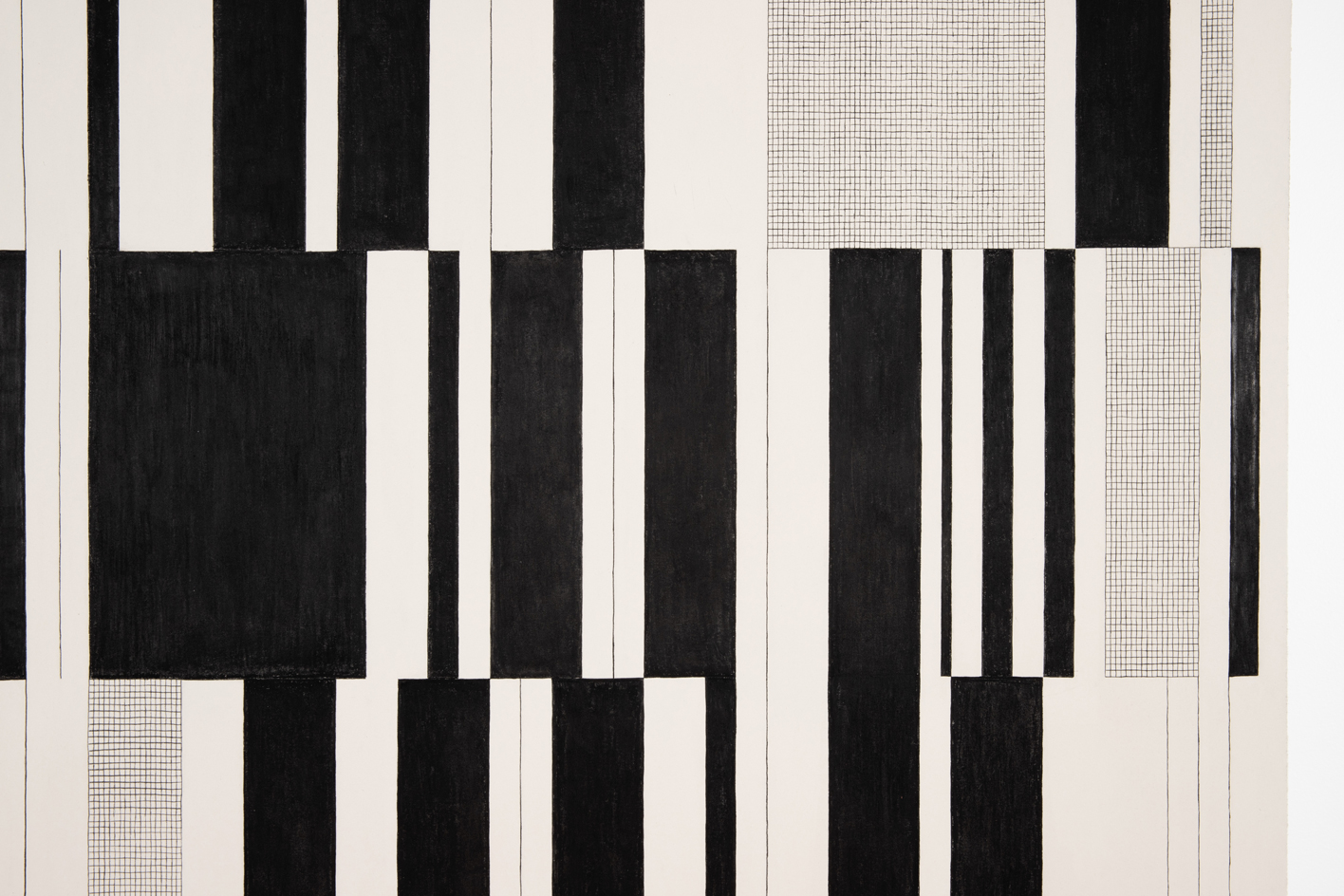

Tyler Hobbs, detail, user_space, 2022

Ironically, part of that ascension means getting physical and Hobbs is doing that at two exhibitions of paintings and drawings in spring 2023, the first at Unit London in early March and another at Pace’s New York gallery later in the month.

Hobbs has long been creating physical versions of his digital work, often using a simple mechanical plotter, followed up with free-hand painting. More recently he has been arming the plotter with a paintbrush (though he admits it’s been a tricky process to get right).

The London show, ‘Mechanical Hand’, pulls together paintings and drawings created over the last three years and, Hobbs says, is his take on the way digital or system approaches and physical processes overlap and blur. ‘It is largely an exploration of how digital art can become more human, and physical art more systematic,’ he says. ‘It’s a mixture of works created by hand, created by machine or created by a combination of the two. It asks, “How can you work with the computer and the machine and in a more human way? And how can you, even when you're working by hand, take a more mechanical approach to work procedurally?” There is a lot of fertile ground there.’

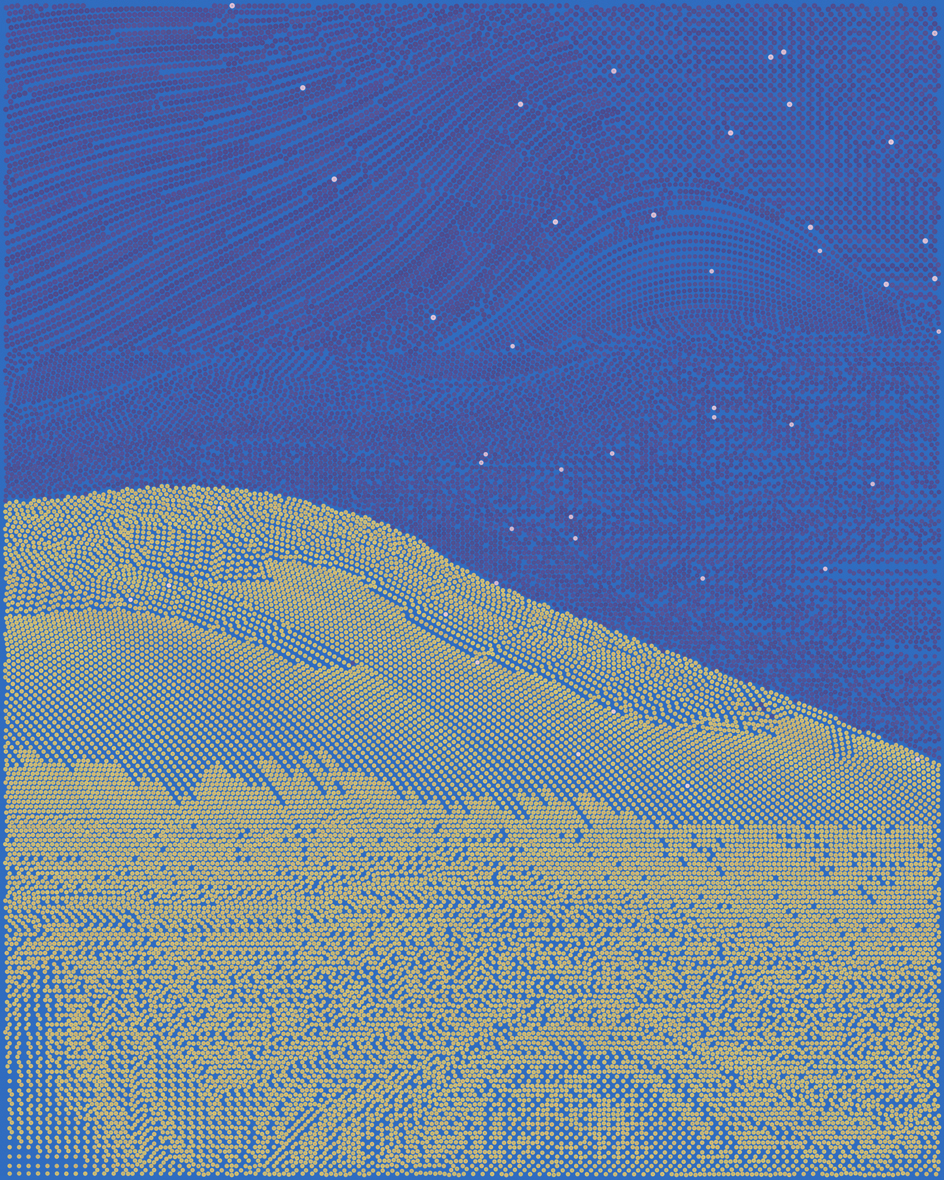

QQL #7, 2022 by Tyler Hobbs and Dandelion Wist, parametric artist sdv.eth

The Pace show ‘QQL: Analogs’, commissioned by the gallery’s Web3 wing Pace Verso, is based around a new series of work produced as part of the QQL project. A collaboration with Dandelion Wist, co-founder of the generative art marketplace Archipelago, QQL comprises a generative algorithm and a website, with visitors free to try it out and even tweak variables, including density, scale and colour (from experience, the results are far more successful when QQL is left to Hobbs’ original devices). Only those who buy a mint pass, though, can actually save and mint an image as an NFT.

The pair released 900 QQL minting passes in September 2022, selling for a total of $17m. A month later they were worth $28m on the secondary market (weeks after the passes had been sold, and even changed hands, most collectors had not actually minted a work; either spending long hours playing with the algorithm to see what they could come up with, hoping it will eventually pop out what generative art enthusiasts call a ‘grail’ piece, or just waiting to see what other collectors released). Hobbs and Wist kept 99 passes for themselves, and the Pace show features 12 of Hobbs' paintings based on his QQL ‘outputs’.

Wallpaper* Newsletter

Receive our daily digest of inspiration, escapism and design stories from around the world direct to your inbox.

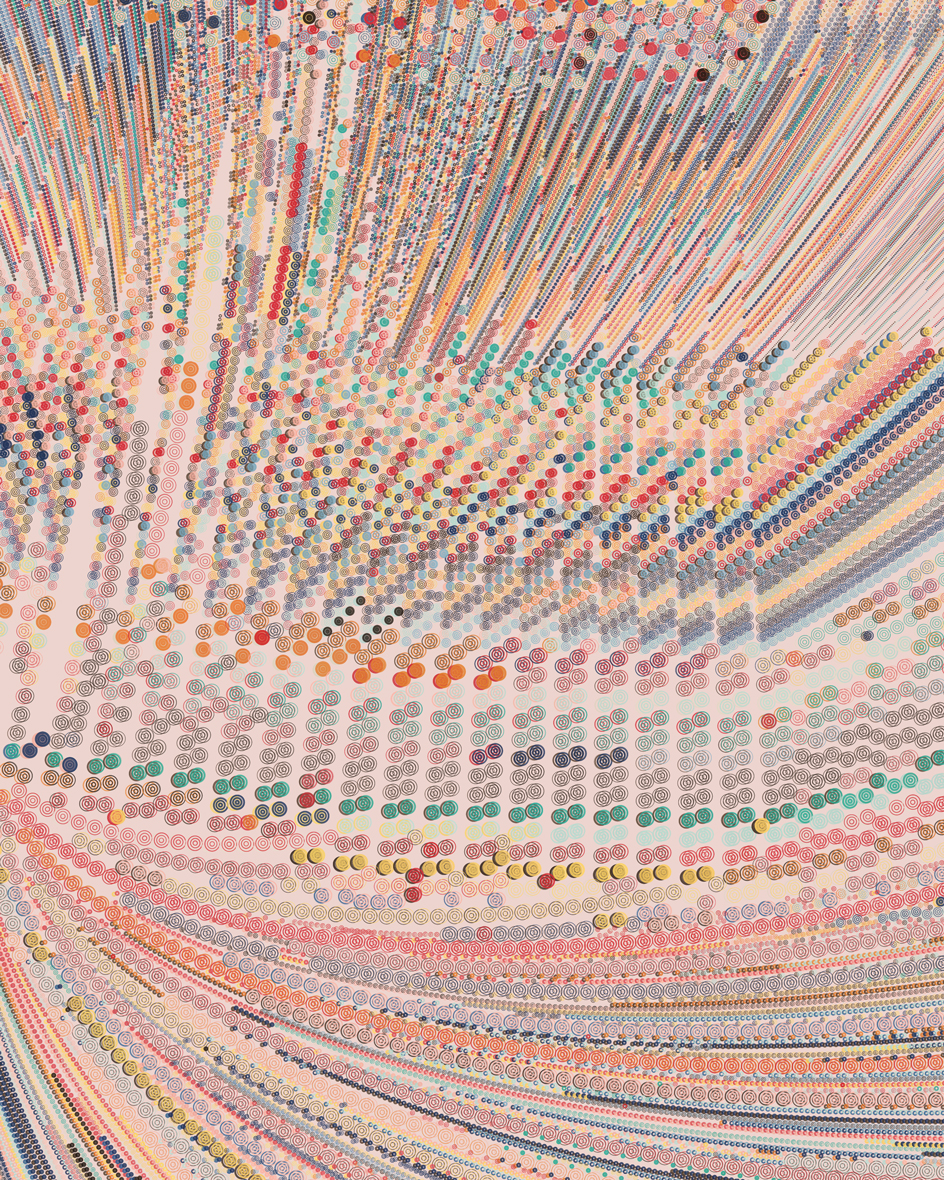

QQL #5, 2022. Tyler Hobbs and Dandelion Wist, parametric artist Antfex.eth

The two shows seem perfectly timed. Just as ChatGPT and the AI image generator Dall-E 2 threaten mass extinction of the creative professions, Hobbs (even though his programs are AI-free) is arguing the case for digital tools in human hands, for the curatorial and creative instinct and the power of the physical experience.

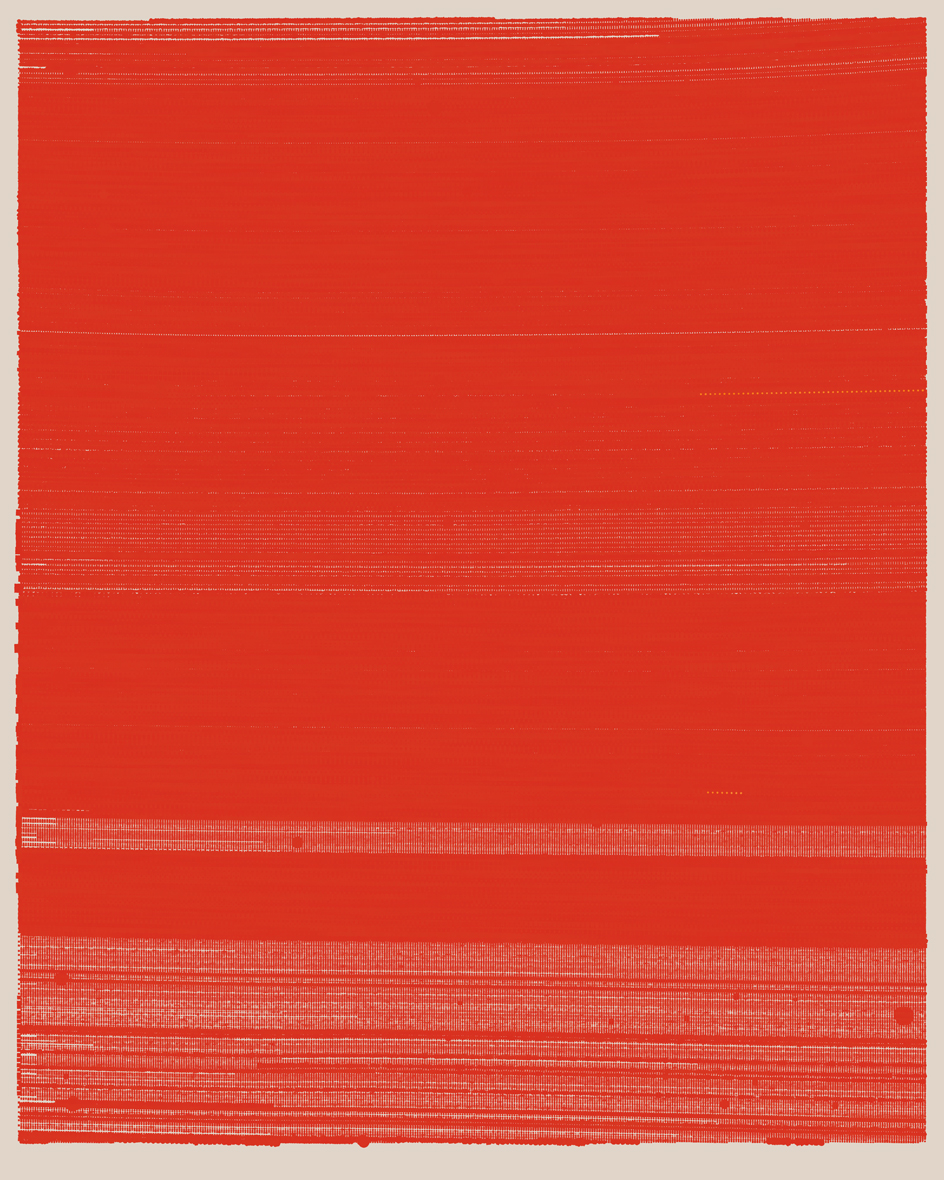

He is clear-sighted about the possibilities and limits of digital creativity. The appeal of generative algorithms, he says, is the ability to create to almost infinite variety, the algorithm delivering thousands of different outcomes, built around countless, or sometimes carefully curated and limited, movable parts. He insists, though, that the curation is everything, the truly creative act, and that the digital work will always pale beside the physical. ‘I’m able to work at a massive scale with millions of lines or dots or elements. So there are these incredible strengths that the computer offers that are completely off-limits to a physical approach. But the digital lacks that special quality that physical art has, it lacks that infinite richness.’

Hobbs’ work has never been about digital sheen and inhuman perfection. There can be no art without happy accidents, faulty connections, intriguing deviations – the odd and unexpected. He always allows space for glitches or even builds in errors in his code. And in the new shows, digital misfires are matched by the inevitable faltering of the human hand. A key attraction of the physical exhibition, he argues, is the ability to really get up close and personal with the art and its imperfections. ‘The physical work has infinite resolution so you can really get closer to those errors and flaws and deviations.’

The shows, though, are also a chance, he says, to fix scale and exercise quality control over the viewing experience. ‘With digital work, there’s a high chance of somebody looking at it on a little phone screen or a monitor where the colours are way off.’ At the new shows, the work is exactly as he intends. You can walk around it, view it from different angles, take in texture and shifts in tone, and the small wobble in a line that won’t disappear with the click of a mouse.

Code as a creative medium

Tyler Hobbs, iostream #1, 2022

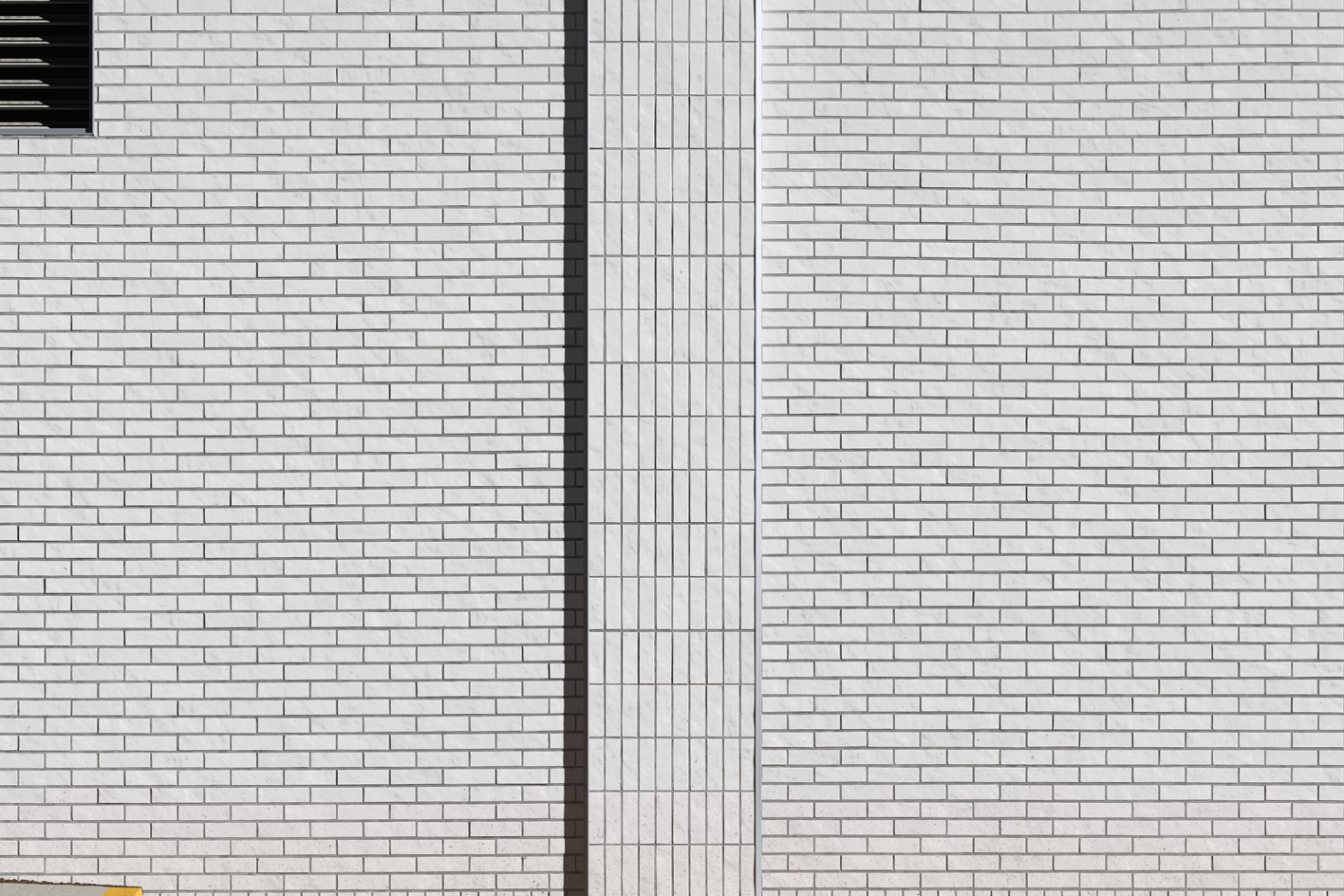

Tyler Hobbs, Aligned Movement

Hobbs has always argued that generative art is not a clean and disruptive break with earlier artistic traditions or day-to-day creative practice. ‘Any artist developing their style, or a particular series, is building an intuitive rule set they follow. That's what gives them a sort of stylistic consistency and they're able to explore all the possible variation within that. I'm doing the same thing but it has to be much more explicit and concrete because I'm working with code as the medium.’

But as much as he denies digital exceptionalism, and loves the physicality of painting and drawing, Hobbs is clear that code is his material. It is his understanding of the potential, and what you can shape with it, that defines his practice. ‘There are so many possibilities with code that just to describe it as a medium is understating the power and importance of it.’

And, as Hobbs points out, code is not just his material of choice. If glass, steel and concrete were the defining materials of the 20th century, then code is the defining world-building material of the 21st century. All of us, he argues, should get better acquainted with what code, and by extension AI, does and how it does it. Art, says Hobbs, is a vital way of doing that. ‘I think it's important artistically to take a closer look at the medium and start to play with it more and to understand it from that perspective. And to develop a healthy relationship to those materials.’

Tyler Hobbs, Wall, 2022

He's certainly pushing for a healthier and friendlier relationship with digital tools in the art world. ‘Computer-based artwork has been panned and widely derided for almost six decades now. And that's an unbelievably long time for the most useful tool that's ever been invented.’ (Hobbs is also a fine and accessible writer and his website includes a number of essays, part championing, part defence, part manifesto, that argue the case for digital and generative art, that insist it can’t be siloed off, sniffed at and dismissed.)

Much of the ignorance and cynicism around Hobbs’ brand of digital art has been based on its entanglement with NFTs and cryptocurrency. But Hobbs insists that recent waves of crypto scandals are ultimately all for the good. 'That kind of volatility and mania is obviously unsustainable, right? That's not good for building a long-term foundation for things.'

Tyler Hobbs, Fidenza #247, 2021

He remains convinced, though, that NFTs and the blockchain are central to the future of art creation and collection. ‘The blockchain is the way that digital art will be collected. I just don't see any alternative. But the people who were in this just for the money or for questionable reasons are being shaken off and now we need to slow down and reflect and start to focus on building a healthy culture, healthy norms and better tools to protect and inform people.’

Despite the Pace show, Hobbs sees no need for more traditional artist representation. He has said that the success of the Fidenza series means that he and his five-strong team could keep working for decades without having to sell another piece.

He is based, almost inevitably, in Austin, Texas, the US’ new tech-meets-creative hot spot (a central Texas native, he grew up 45 minutes from the city). And working digitally means he can stay exactly where he is. He is in a good place but remains driven by almost evangelical zeal.

Tyler Hobbs, Days Fade, 2022

Hobbs could be the generative artist who finally breaks through, who finally gets the art world to accept the potential of digital tools, of code as a material. More than that, he might be the model for how all creatives understand and leverage the arrival of artificial ‘creative’ intelligence. ‘You need to approach it from a place of curiosity,’ he argues, ‘consider how you can use these tools to unlock new and better forms of expression, how you can use them to improve your work or create an entirely new type of work that doesn't exist yet. Because that's going to happen. These tools are so powerful, they're going to drastically change how all of these things are done, so you have to find ways to embrace them.’

‘Mechanical Hand’ runs at Unit London from 7 March-6 April 2023. unitlondon.com

‘QQL: Analogs’, is at Pace New York from 30 March-22 April 2023. pacegallery.com

-

Put these emerging artists on your radar

Put these emerging artists on your radarThis crop of six new talents is poised to shake up the art world. Get to know them now

By Tianna Williams

-

Dining at Pyrá feels like a Mediterranean kiss on both cheeks

Dining at Pyrá feels like a Mediterranean kiss on both cheeksDesigned by House of Dré, this Lonsdale Road addition dishes up an enticing fusion of Greek and Spanish cooking

By Sofia de la Cruz

-

Creased, crumpled: S/S 2025 menswear is about clothes that have ‘lived a life’

Creased, crumpled: S/S 2025 menswear is about clothes that have ‘lived a life’The S/S 2025 menswear collections see designers embrace the creased and the crumpled, conjuring a mood of laidback languor that ran through the season – captured here by photographer Steve Harnacke and stylist Nicola Neri for Wallpaper*

By Jack Moss