The Barbican as muse: composer Shiva Feshareki on bringing the brutalist icon to life through music

For the last two years, British-Iranian experimental composer and turntablist Shiva Feshareki has been drawing on the Barbican’s hidden history as a gateway for her new piece. She talks to Wallpaper* about her Brutalist muse

Whether you love or loathe the concrete geometry of the iconic Barbican estate, it tends to inspire strong feelings: for every Londoner charmed by its sharp Brutalist architecture, you’ll find another person just as eager to brand it an eyesore.

First constructed in post World War II London by architects Chamberlin, Powell and Bon, the sprawling complex aimed to revive an area of the capital that had been devastated by bombing, but was originally the site of a Roman fortress, marking the gateway passage through London’s walls, and into the ancient city. Created with a Utopian vision in mind, and inspired by the fortress that used to stand here – both in name and its construction – this city within a city now contains a huge performing arts centre, a tranquil, one-hectare lake, and a hidden conservatory packed with tropical plants.

And for the last two years, British-Iranian experimental composer and turntablist Shiva Feshareki has been drawing on the Barbican’s hidden history as a gateway for her new piece, 'Bab-Khaneh: Gatehouse of Memory'. The work’s title refers to the ancient Persian word ‘Bab-Khaneh’ – thought to be a possible origin of the word Barbican – and Feshareki has imagined the project as a sonic survey of the Barbican Hall’s acoustics and design.

If you’re not already familiar with Shiva Feshareki, her work is part of a rich lineage of experimental composition, drawing on everything from musique concrète pioneer Daphne Oram to warped, acid-flecked dub. In essence, the Ivor Novello-winning artist offers up a fascinating exploration of how sound moves through space, incorporating turntables, orchestras, cutting-edge ambisonic technology, choirs, and bespoke art installations to bend, morph, and reshape sound as we know it.

On February 23, Feshareki will perform 'Bab-Khaneh: Gatehouse of Memory' within the complex’s wooden-panelled concert hall, accompanied by her trademark turntables, the BBC Symphony orchestra, and the building itself: which will be used as a kind of instrument during the intricate live performance. Ahead of its world premiere, Wallpaper* caught up with Feshareki to learn more.

You’ve been developing Bab-Khaneh: Gatehouse of Memory since 2023. Could you walk me through the concept for the piece?

SF: 'All the elements of the sounds [in Bab-Khaneh: Gatehouse of Memory] are reacting and responding to the acoustics and architectural design and material of the Barbican Hall; the hall itself is the starting point of how the sound manifests live in the moment.

Wallpaper* Newsletter

Receive our daily digest of inspiration, escapism and design stories from around the world direct to your inbox.

One of the first things I noticed when I went for the first site visit at the Barbican Hall were the wooden panels that stretch across the sides of the walls; I just thought straight away that if we can actually put speakers inside, and directing into, the holes of these wooden pipes, I can literally play the hall [as a kind of instrument] by firing electronic sound into the walls and ceiling, and sounding the acoustics, material design and architecture of the space. It's almost like an orchestra of speakers, positioned geometrically all over the space, in corners, in between materials and in crevices. On stage, we’ll also have an IKO; a 20 sided speaker projecting 360 degrees outwards from the stage... so that it really absorbs the acoustics of the hall and all of its qualities from the stage. All of this will both surround the audience in ambisonic sound, but also reflect and deflect off the material design of the hall. During the performance, I’ll compose electronic sound live, in response to the acoustics, and what's happening in the space, and then build up the sound from there.

I'll also be responding to the orchestra's performance, using a variety of analogue electronic instruments, from Vintage Space echoes and tape echoes to turntables, and CDJs; I’ll be repurposing DJ technology to create this live electronic sound. And then finally, there's the full BBC Symphony Orchestra; a really large orchestra made up of about 70 orchestral members. The way it’s composed, every single member of the orchestra is essentially playing a separate composition, kind of like they're each following their own trajectory. The idea is to enhance the sculptural perspective of sound, so that instead of everybody playing one composition, which then becomes linear from 0 to 50 minutes, there are 70 compositions happening, all at the same time.

When you're experiencing the composition as an audience member, you'll feel how all of these different strands are at one with each other, interacting in the same space. And the heart of it is the architecture and design of the hall, which brings everything together.'

Every audience member will also perceive the piece differently, whether that is to do with their own physical hearing, their positioning in the room, or the memories and preconceptions they project onto the music as a listener. That must add an additional layer to the idea that this is a very collaborative experience, too?

SF: 'Yeah, it plays on everybody's unique perceptions; that is a fundamental element of the composition. Wherever you're sitting in the space, you're receiving a completely unique and different experience of the work. It's a bit like if there’s a physical sculpture, and you're just standing at one point and viewing that sculpture from that one perspective; it's going to look very different to the person who is only viewing it from the other side. What I've been trying to do is to capture that. I think there's a real magic to the intangibility of sound; while you can't tangibly see it, you can feel the vibrations, and everybody receives a different sonic, sculptural perspective, wherever they're sat. That's what this piece is all about, really.

The way that I have composed it is also, in a way, trying to juxtapose two ideas: it's highlighting individualistic expression, but it's also highlighting how everything is predetermined in a moment, in a way that is outside of our control. This piece is very much playing on that: inwards into the soul, and outwards into a space and beyond. And that idea is very much a part of my Iranian upbringing. Most Iranians will be able to say that they have been brought up with festivals like Spring Equinox, Winter Solstice, and the Persian New Year. Geometry is such an important part of our culture; our upbringing is very connected to trance, and spirituality, and the universe, and how everything is interconnected through this kind of geometry and flux.'

The Barbican itself is a divisive building: it really seems to split opinion. How do you feel about it?

SF: 'I'm obsessed with it! I wanted to do this project because I was brought up coming to the Barbican as a child, as a teenager, and I have a real personal connection to it. I’ve seen so many events here, both as a child, and as an adult. I have a real love and passion for its very unique take on Brutalism and I often go on the Barbican architecture tours. I actually came up with the idea for this project, and proposed it to the Barbican, after being inspired by the last tour I went on.'

You have always used turntables as part of your practice; something that most people probably associate much more closely with dance music culture and DJing. Where did that curiosity around repurposing that kind of technology come from?

SF: 'In my late teens, I started to go to parties with really great scratch DJs, just as I started composing in quite a committed way. At the time, anything that was interesting to me, I was thinking: "Well, how do I involve this into one of my compositions?" I remember being really fascinated by the turntable as a moving sculpture. I was watching the DJ scratching, and I was just thinking: "wow, that's such a visceral thing". They speed up, slow down, and reverse and manipulate a physical record with this motion-based manipulation, and these moving circles. That was the starting point, and I think my instrumental composition grew side by side with my turntablism. Whereas my kind of acoustic composition was something that was really refined and academic, and painstaking, I felt that my turntable has always been this really playful element, kind of at the opposite end. What has been amazing about the turntables is how many interesting cultures I've been let into.'

For most people, turntablism is an essential part of genres like early hip-hop, and dub. Did you draw on either of those genres initially?

SF: From the very start, my work was inspired by dub culture; that was the starting point, and from there, it expanded into different realms that I never would have really imagined. I was brought up in Notting Hill as well, so that’s another really important element of my upbringing.

Prior to dub, the history of turntablism also goes way back to the late 1940s, and the experimental pioneer Daphne Oram – who I know is a hugely influential figure for you. Do you remember when you discovered her work, and the effect it had on you?

SF: 'It was a little bit later on in my turntabling life, in my mid-20s. It was through a bit of research that I came across her work, and I was just blown away; it had such a massive impact on me, and it inspired me so much that I wanted to delve deeper. I went to the Daphne Oram collection at Goldsmiths University to research, because I wanted to do a radio show on her music, and that's where I came across Still Point, which is a piece she composed when she was 23, in 1948. The score actually specifies live turntable manipulation of recorded discs, in duet with orchestral writing. She was working as a sound engineer during the World War when she composed it, and it preempted so many developments in music technology. I think the reason why [women such as Oram] were coming up with all these radical and unique ideas was because they were working so independently, and they weren't actually working with orchestras or other musical forms in society. It meant that they could work in a very individualistic way, a more free and playful way. These ideas were so forward-thinking, and it's only decades later that we’ve caught up with them.'

Suzanne Ciani, another hugely influential artist who did very pioneering, early work with synthesisers in the 1970s, told me that she discovered Daphne Oram through watching your BBC Proms performance of Still Points in 2018, and found it so moving that she cried...

SF: 'That’s amazing, I’m so touched that she felt that way. I also remember when I first came across the score; all these loose pieces of paper, and it had never been performed. I also burst out crying. I remember just being like: ‘how can this have happened?’. I just felt like I needed to find a way to get that piece performed. I really felt so emotional about it.'

Ciani also shared a saying which she keeps in mind when things go wrong during performances: 'the bigger the disaster, the better the outcome'. Do you relate to that in any way?

SF: 'I've had so many experiences of things going terribly wrong beforehand, and me just being like: I'm just going to go for it and just use it. It's actually really defined lots of things that are happening in this Barbican piece. I had a concert last year where the sound system completely malfunctioned, which meant only, like, an eighth of the sound that I was producing was coming out of the speakers. What happened was that I was able to start working with the sound by spinning it really, really, really fast in the space, which I normally wouldn't do because it would be dizzying. Instead, because there were so many silences, it was creating what I call now a sonic strobe. Because there was this malfunction, it was really interacting with the acoustics of the space and the choir who were involved in the piece. It was extremely trippy.

This entire Acousmonium that I've designed with my colleague Dan Hulme, for the Barbican performance, is completely inspired by that. The entire sound system is loads of different sound strokes, occurring at different angles, and at different positions in the hall, be it in the ceiling or at the back or on stage side panels. It’s kind of a misuse of the technology, but when the sound cuts out, that's when you hear the hall.'

Shiva will perform 'Bab-Khaneh' at Barbican on 23 February 2025. Get tickets.

El Hunt is a London-based journalist, covering music, culture, and LGBTQ+ issues. A former NME staff writer, and a former commissioning editor at the Evening Standard, she is now a freelance writer, and has contributed to the likes of The Guardian, Wallpaper, BBC, Vice, Cosmopolitan, and Time Out London.

-

Carine Roitfeld on the magic of Dior

Carine Roitfeld on the magic of DiorThe legendary fashion editor has teamed up with photographer Brigitte Niedermair on a special look into the famed French house's archives as part of the UBS House of Craft x Dior in New York

-

Kvadrat’s new ‘holy grail’ product by Peter Saville is inspired by spray-painted sheep

Kvadrat’s new ‘holy grail’ product by Peter Saville is inspired by spray-painted sheepThe new ‘Technicolour’ textile range celebrates Britain's craftsmanship, colourful sheep, and drizzly weather – and its designer would love it on a sofa

-

MillerKnoll's new archive is a design lover's paradise

MillerKnoll's new archive is a design lover's paradiseThe furniture design powerhouse is opening its vaults to scholars and enthusiasts like. Take a peek inside

-

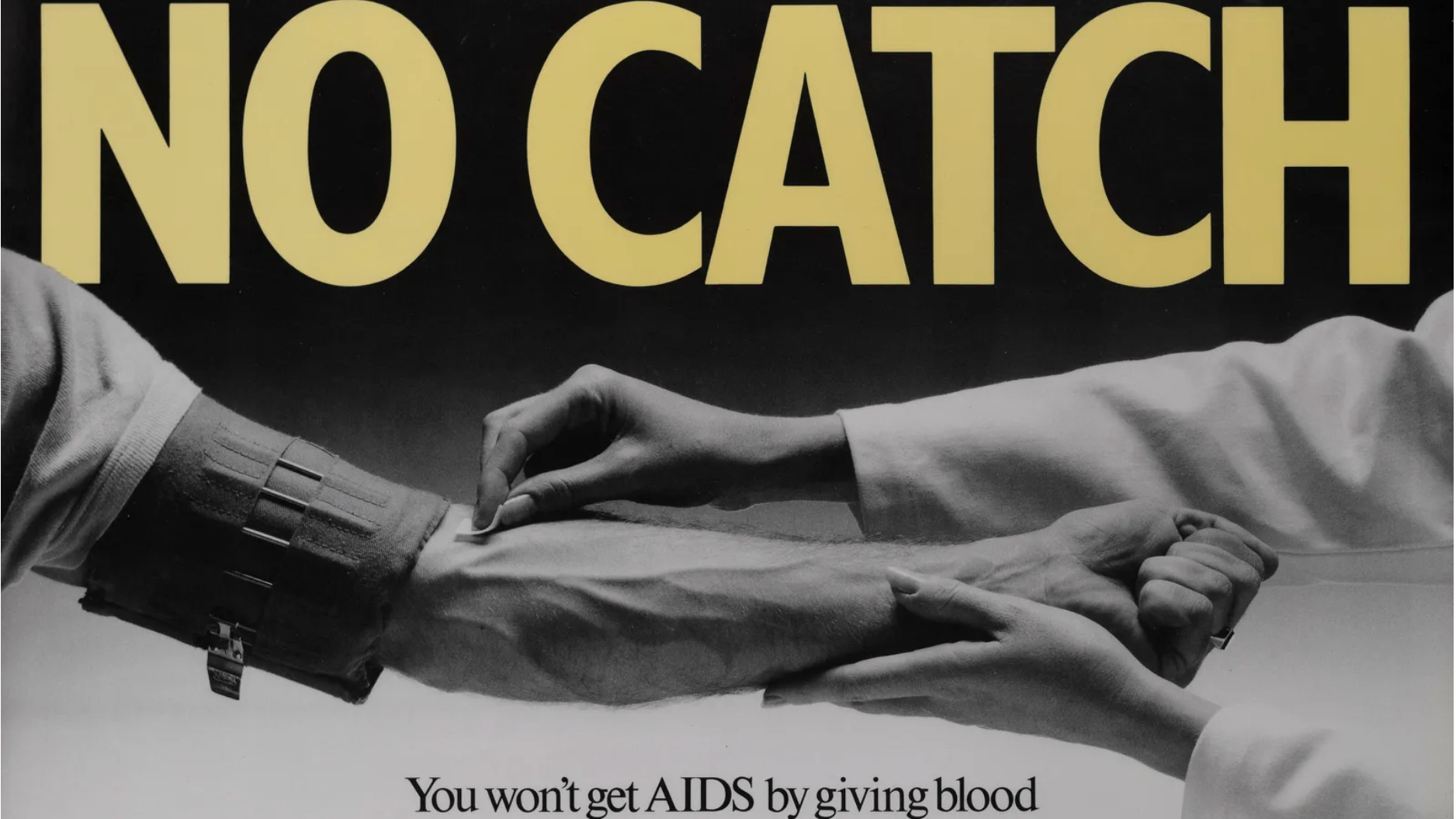

Sexual health since 1987: archival LGBTQIA+ posters on show at Studio Voltaire

Sexual health since 1987: archival LGBTQIA+ posters on show at Studio VoltaireA look back at how grassroots movements emphasised the need for effective sexual health for the LGBTQIA+ community with a host of playful and informative posters, now part of a London exhibition

-

Ten things to see at London Gallery Weekend

Ten things to see at London Gallery WeekendAs 125 galleries across London take part from 6-8 June 2025, here are ten things not to miss, from David Hockney’s ‘Love’ series to Kayode Ojo’s look at the superficiality of taste

-

Out of office: what the Wallpaper* editors have been up to this week

Out of office: what the Wallpaper* editors have been up to this weekThis week saw the Wallpaper* team jet-setting to Jordan and New York; those of us left in London had to make do with being transported via the power of music at rooftop bars, live sets and hologram performances

-

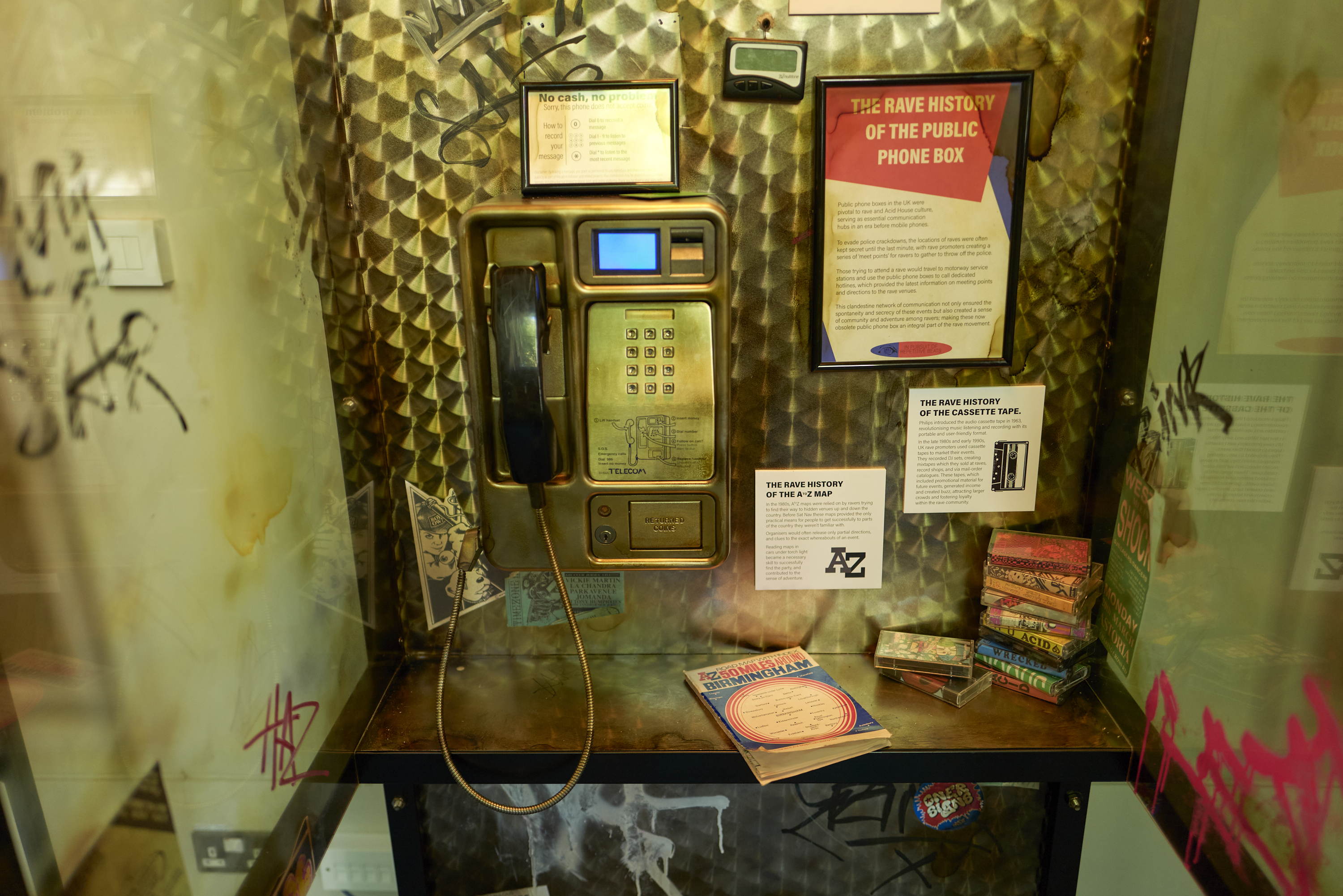

Be transported to an illegal Acid House rave by the Barbican's new immersive experience

Be transported to an illegal Acid House rave by the Barbican's new immersive experienceVirtual reality, DJ sets, record label takeovers – it's all at the Barbican through to August. Craig McLean gets out his glowsticks

-

Out of office: what the Wallpaper* editors have been up to this week

Out of office: what the Wallpaper* editors have been up to this weekThe Wallpaper* team enjoyed good art, food and drink this week, attending various exhibition openings and unearthing some of the best pasta and cocktails that London has to offer

-

As Photo London turns 10, seven photographers tell us the story behind their portraits

As Photo London turns 10, seven photographers tell us the story behind their portraitsPhoto London celebrates its tenth anniversary from 14–18 May 2025 at Somerset House

-

The Tate Modern is hosting a weekend of free events. Here's what to see

The Tate Modern is hosting a weekend of free events. Here's what to seeFrom 9 -12 May, check out art, attend a lecture, or get your groove on during the museum's epic Birthday Weekender

-

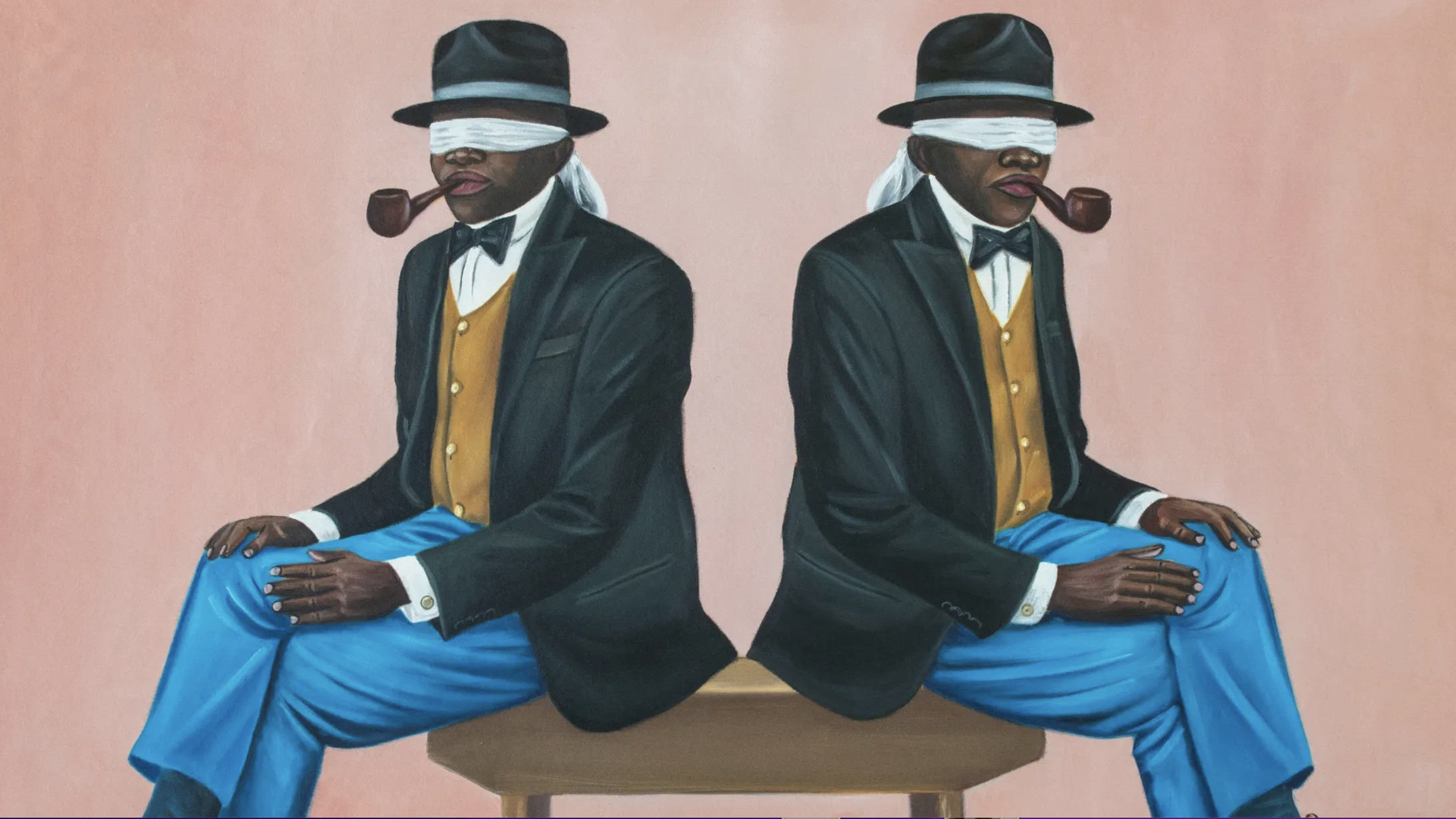

Artist Zumba Luzamba on the vibrant aesthetic of Congolese fashion rebels, the sapeurs

Artist Zumba Luzamba on the vibrant aesthetic of Congolese fashion rebels, the sapeursThe Congolese artist takes a deep dive into a fashion subculture in his show at London's Kristin Hjellegjerde Gallery. ‘I draw people in with style so that they can sit with deeper themes,’ he says