The complicated and ‘incomplete’ legacy of Nobuyoshi Araki

He is Japan’s most famous photographer and has defined the Western image of Japanese sexuality since he started taking pictures of Tokyo’s anything-goes sex scene in the 1960s: but what else is there to learn about the hugely influential Nobuyoshi Araki?

An ‘incomplete’ retrospective in New York gets to grips with the complexities of the vast oeuvre of the voracious photographer and his larger-than-life public image. ‘He’s not easy; he’s much more complex than the cuddly persona he projects,’ says New York’s Museum of Sex artistic and creative director Serge Becker, who first encountered Araki’s work in the 1990s. ‘Beyond the hype and controversies, there’s actually a real artist and thinker of substance. He’s on the level of Andy Warhol in regards to his prescience about art and culture.’

Those controversies include his inexhaustible depictions of kinbaku-bi, Japanese rope bondage, some of them extreme, especially for an outsider. ‘I tie women’s bodies up because I know their souls can’t be tied. Only the physical self can be tied,’ the artist told the Huffington Post in 2014, by way of explanation. ‘Putting a rope round a woman is like putting an arm round her.’ In the 1980s, Araki also directed a porn film that panned with fans and didn’t win him many.

‘There’s a picture of [Yōko] sleeping on a boat on the Yanagawa River,’ Araki has said, about one of his favourite images from the Sentimental Journey series (1971-2017). ‘It was our honeymoon, so she was exhausted from all the sex. In Japan we say that you cross the Sanzu River when you depart to the “other world”. I had no intention of taking a picture like that so I feel like maybe God or someone made me take that picture. Her posture is like that of a fetus.’ Courtesy of Taka Ishii Gallery, Tokyo

Becker is part of the impetus behind what is the largest ever exhibition of the artist’s work in the US, titled ‘The Incomplete Araki: Sex, Life, and Death in the Works of Nobuyoshi Araki’. The show aims to present different facets to the artist and his interests, through a selection of more than 500 polaroids and 400 photobooks – the latter an important part of Araki’s work from the beginning, and one of the many significant contributions he has made to contemporary photography over the past five decades.

Araki’s legacy is as complicated as the artist, who is one of the most prolific of his generation: despite his fascination with physical bondage, he represents freedom in the arts and life. At the same time, his images of women have also been slammed as objectifying and contributing to a sexual stereotype – if not inventing it for the visual generation, and implicate him in an industry of sex that has not typically favoured women.

‘He ventures in his work and private life into areas that many of us are uncomfortable with,’ Becker suggests. ‘Some of the discomfort is not necessarily because we disagree with him, but because he touches us and shows us aspects of ourselves we tend to cover up. He’s brutally honest, but he gets to do it, because he shows us love and beauty too.’

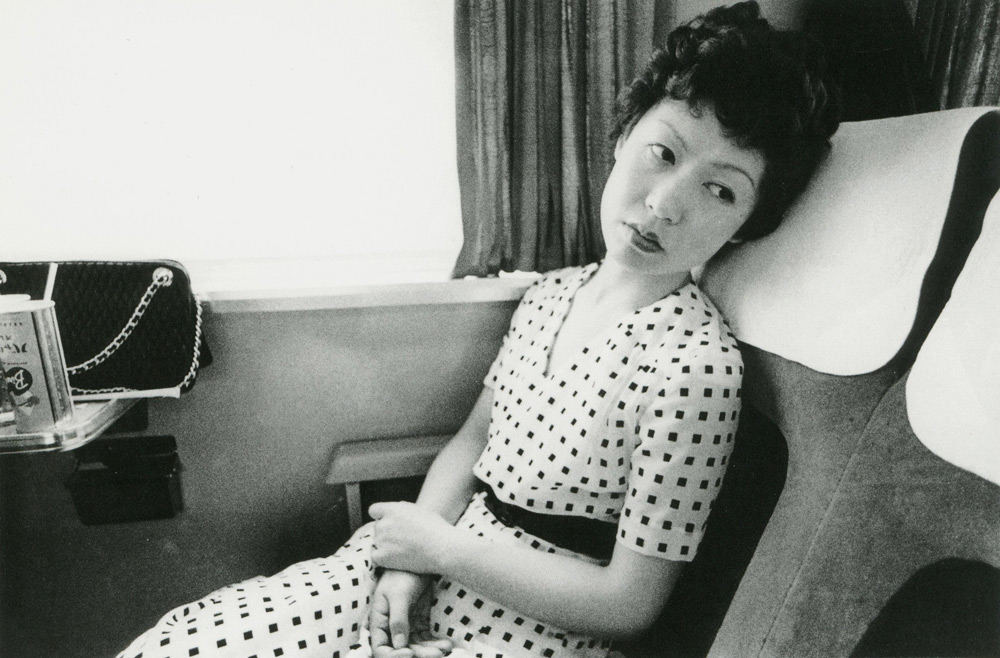

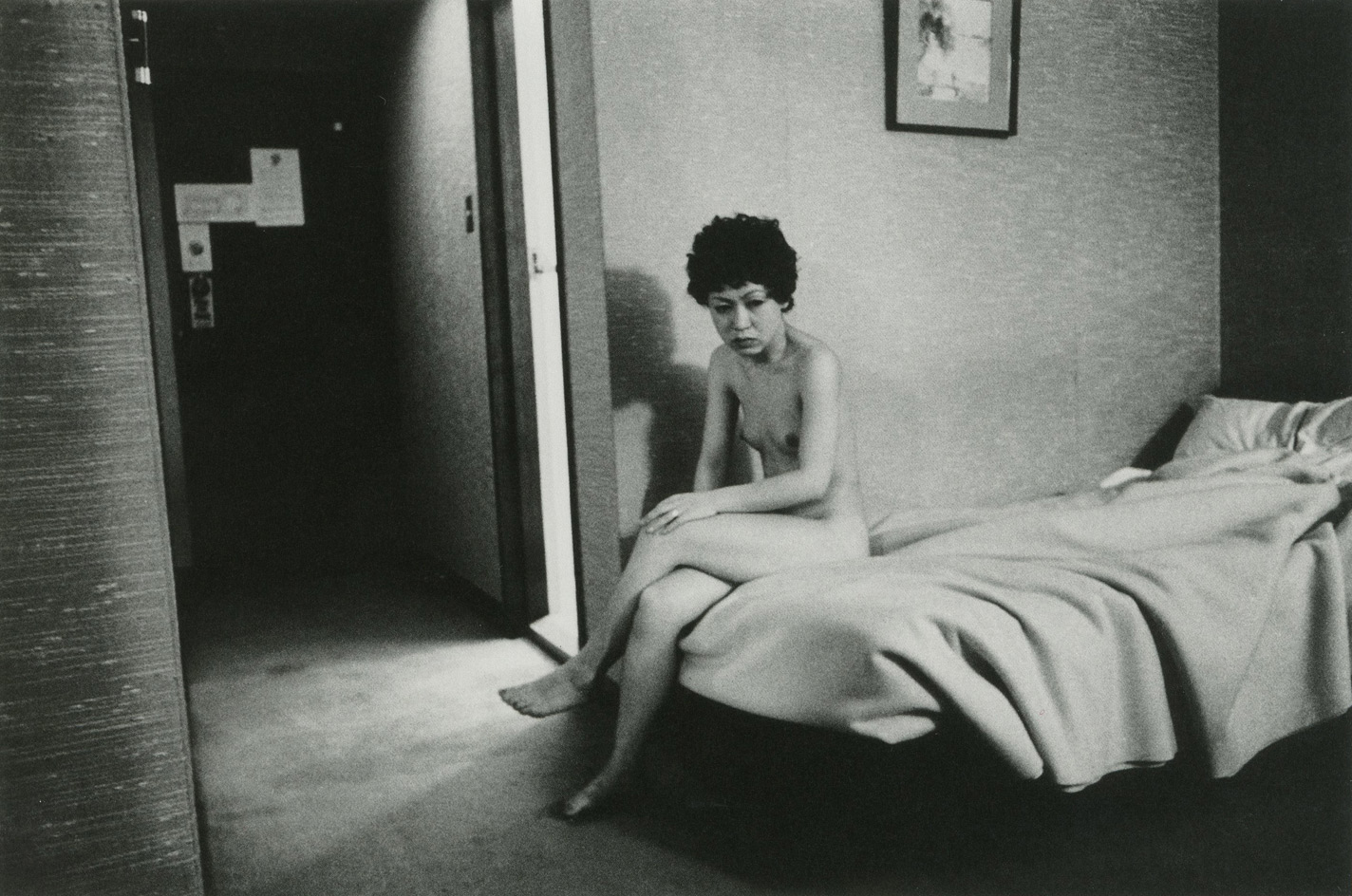

Sentimental Journey, 1971-2017, by Nobuyoshi Araki. Courtesy of Taka Ishii Gallery, Tokyo

Beneath the brazen appeal of the archetypal Araki picture – black and white, high exposure, youthful naked skin – Araki has more to show us about the murky waters of what we are, and what he is. Hurtling from erotica to hardcore porn, into tender documents of his late wife Yōko and wistful portraits of his cat, Chiro, Araki was way ahead of the game in the way he mixed the personal and the public, forging an ambiguous narrative of fact and fantasy with his lens.

‘We live in many ways in a world he helped shape, and we have adopted his language. The creation of the personal brand, the ceaseless documentation of one’s lives, the lack of privacy and sharing of personal moments, the high and the low of it all,’ Becker reflects.

In the current atmosphere of #MeToo revelations, the question is whether we need more visions of male fantasy for the future. Perhaps it’s time for a new language.

(Warning: the following images contain nudity.)

Sentimental Journey, 1971-2017, by Nobuyoshi Araki. Courtesy of Taka Ishii Gallery, Tokyo

Flowers, 1985, by Nobuyoshi Araki. Courtesy of Private Collection

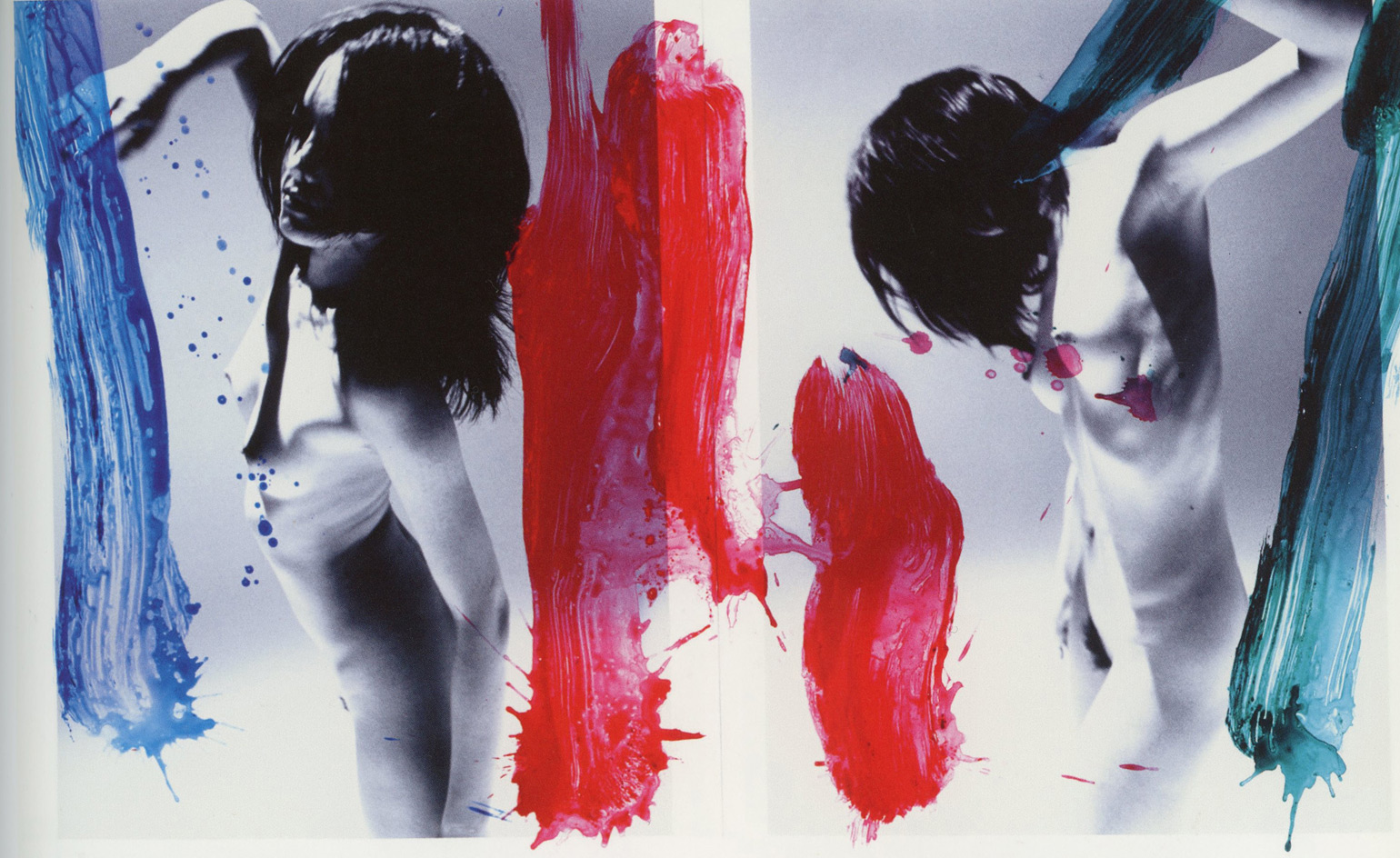

KaoRi Love (Diptych), 2007, by Nobuyoshi Araki. Kaori has been Araki’s muse and lover since the early 2000s. This series comprises photographic portraits of Kaori, which are splashed and scrawled with acrylic paint. The paint here also plays an ambiguous role as the trace of the artist’s hand – while the photographs may expose Kaori and her body, often the paint is used as a way to then partially cover or obscure her. Courtesy of Private Collection

INFORMATION

‘The Incomplete Araki: Sex, Life, and Death in the Work of Nobuyoshi Araki’ is on view until 31 August. For more information, visit the Museum of Sex website

ADDRESS

Museum of Sex

233 Fifth Avenue

New York

Wallpaper* Newsletter

Receive our daily digest of inspiration, escapism and design stories from around the world direct to your inbox.

Charlotte Jansen is a journalist and the author of two books on photography, Girl on Girl (2017) and Photography Now (2021). She is commissioning editor at Elephant magazine and has written on contemporary art and culture for The Guardian, the Financial Times, ELLE, the British Journal of Photography, Frieze and Artsy. Jansen is also presenter of Dior Talks podcast series, The Female Gaze.

-

Tour the best contemporary tea houses around the world

Tour the best contemporary tea houses around the worldCelebrate the world’s most unique tea houses, from Melbourne to Stockholm, with a new book by Wallpaper’s Léa Teuscher

By Léa Teuscher

-

‘Humour is foundational’: artist Ella Kruglyanskaya on painting as a ‘highly questionable’ pursuit

‘Humour is foundational’: artist Ella Kruglyanskaya on painting as a ‘highly questionable’ pursuitElla Kruglyanskaya’s exhibition, ‘Shadows’ at Thomas Dane Gallery, is the first in a series of three this year, with openings in Basel and New York to follow

By Hannah Silver

-

Australian bathhouse ‘About Time’ bridges softness and brutalism

Australian bathhouse ‘About Time’ bridges softness and brutalism‘About Time’, an Australian bathhouse designed by Goss Studio, balances brutalist architecture and the softness of natural patina in a Japanese-inspired wellness hub

By Ellie Stathaki

-

Leonard Baby's paintings reflect on his fundamentalist upbringing, a decade after he left the church

Leonard Baby's paintings reflect on his fundamentalist upbringing, a decade after he left the churchThe American artist considers depression and the suppressed queerness of his childhood in a series of intensely personal paintings, on show at Half Gallery, New York

By Orla Brennan

-

Desert X 2025 review: a new American dream grows in the Coachella Valley

Desert X 2025 review: a new American dream grows in the Coachella ValleyWill Jennings reports from the epic California art festival. Here are the highlights

By Will Jennings

-

This rainbow-coloured flower show was inspired by Luis Barragán's architecture

This rainbow-coloured flower show was inspired by Luis Barragán's architectureModernism shows off its flowery side at the New York Botanical Garden's annual orchid show.

By Tianna Williams

-

‘Psychedelic art palace’ Meow Wolf is coming to New York

‘Psychedelic art palace’ Meow Wolf is coming to New YorkThe ultimate immersive exhibition, which combines art and theatre in its surreal shows, is opening a seventh outpost in The Seaport neighbourhood

By Anna Solomon

-

Wim Wenders’ photographs of moody Americana capture the themes in the director’s iconic films

Wim Wenders’ photographs of moody Americana capture the themes in the director’s iconic films'Driving without a destination is my greatest passion,' says Wenders. whose new exhibition has opened in New York’s Howard Greenberg Gallery

By Osman Can Yerebakan

-

20 years on, ‘The Gates’ makes a digital return to Central Park

20 years on, ‘The Gates’ makes a digital return to Central ParkThe 2005 installation ‘The Gates’ by Christo and Jeanne-Claude marks its 20th anniversary with a digital comeback, relived through the lens of your phone

By Tianna Williams

-

In ‘The Last Showgirl’, nostalgia is a drug like any other

In ‘The Last Showgirl’, nostalgia is a drug like any otherGia Coppola takes us to Las Vegas after the party has ended in new film starring Pamela Anderson, The Last Showgirl

By Billie Walker

-

‘American Photography’: centuries-spanning show reveals timely truths

‘American Photography’: centuries-spanning show reveals timely truthsAt the Rijksmuseum in Amsterdam, Europe’s first major survey of American photography reveals the contradictions and complexities that have long defined this world superpower

By Daisy Woodward