Dana Lixenberg captures over 20 years in LA’s Imperial Courts

In October, Amsterdam and New York-based Dana Lixenberg loaded her car with copies of her new book Imperial Courts 1993–2015 and drove to the town of Watts in Los Angeles. The books were a gift to the residents of Imperial Courts, an overwhelmingly African-American estate in South LA, who were looking forward to seeing the woman they know as the ‘picture lady’, who has been photographing their families in the past 22 years.

The story of the Dutch photographer’s bond with Imperial Courts began in 1993 when she was assigned by the Dutch magazine, Vrij Nederland, to document the reconstruction of the area, which had been wrecked by racial riots. The community’s frustration and isolation moved her to start the project.

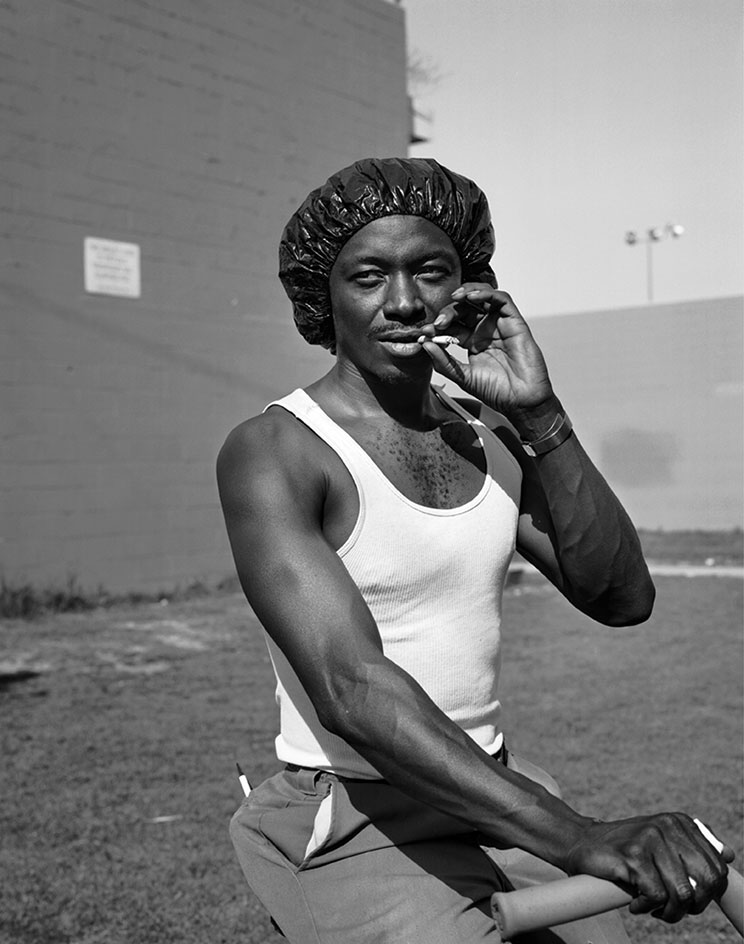

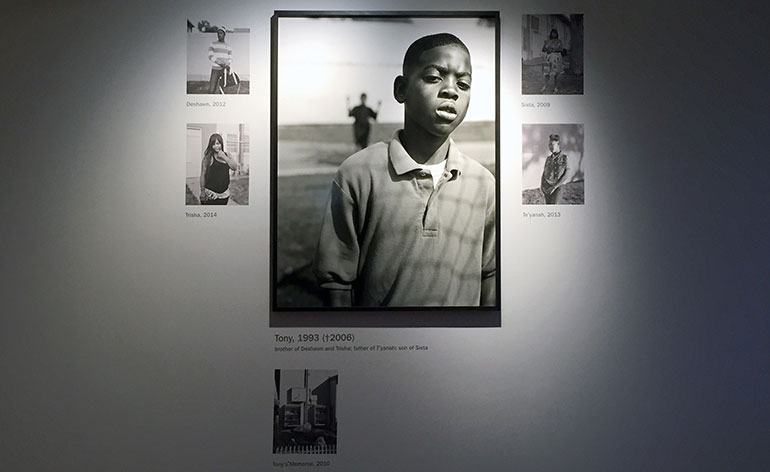

She was not granted easy access; Tony Bogard, then leader of a major neighbourhood gang, had wanted to know: ‘What do we get out of it?’ In her book, Lixenberg admits, ‘I still can’t really answer his question. What do photographs give to people, outside of the opportunity to remember our past and those we might otherwise forget?’ People were reluctant, at first, but working with a large, awkward camera (a 4x5 large format film camera) and gifting Polaroids must have helped her to win people over.

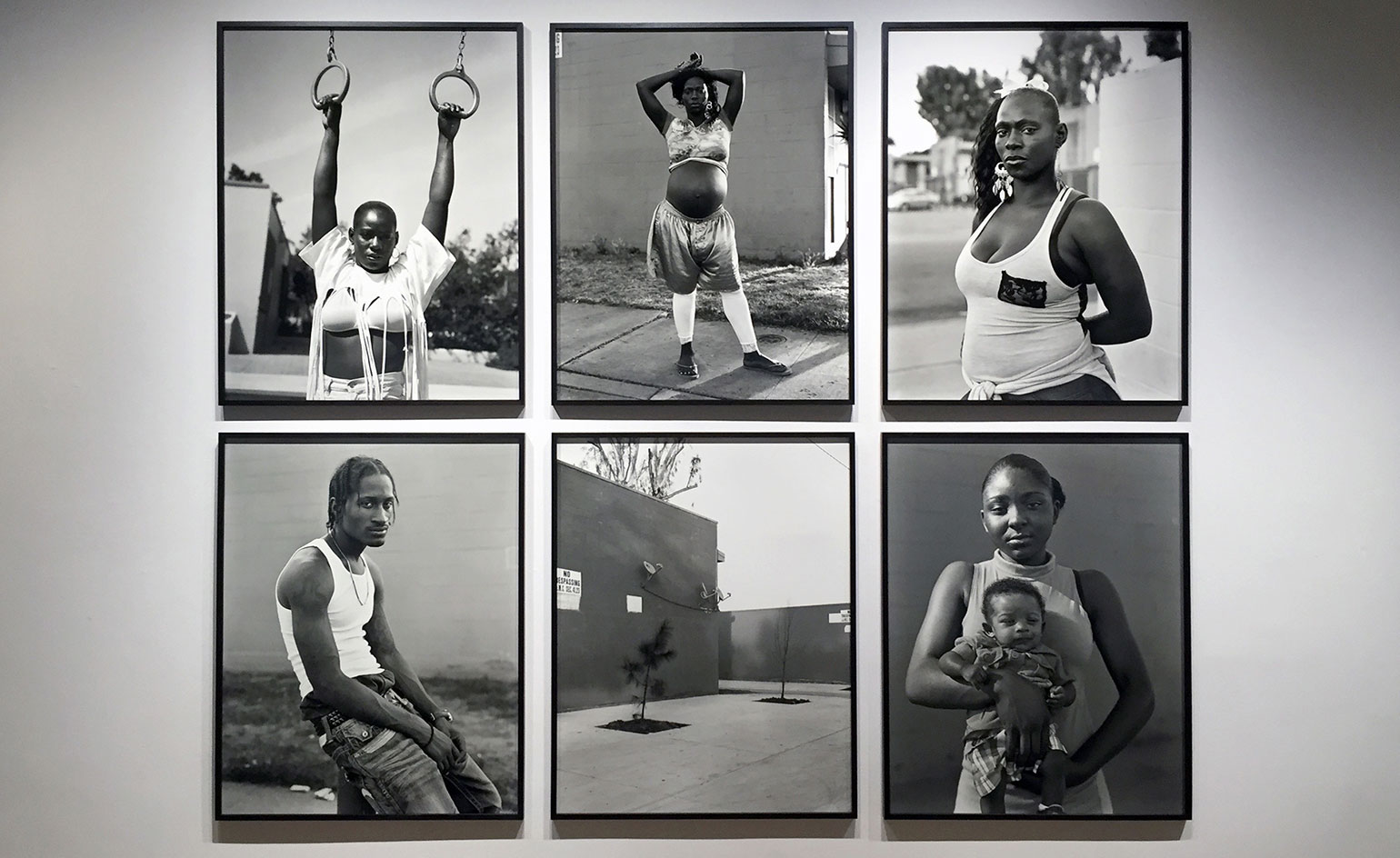

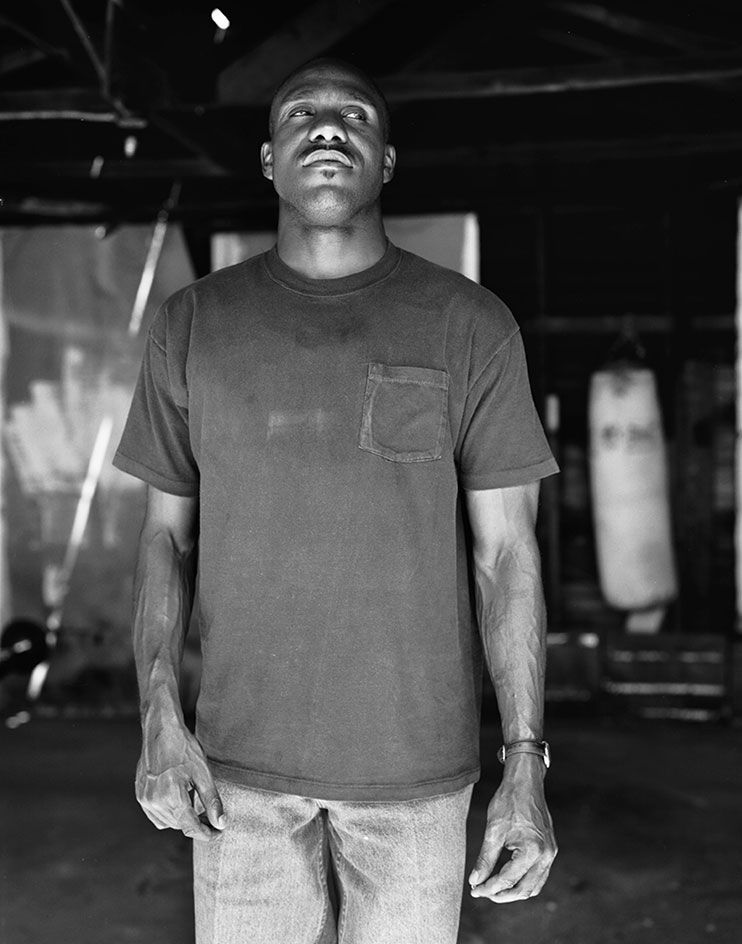

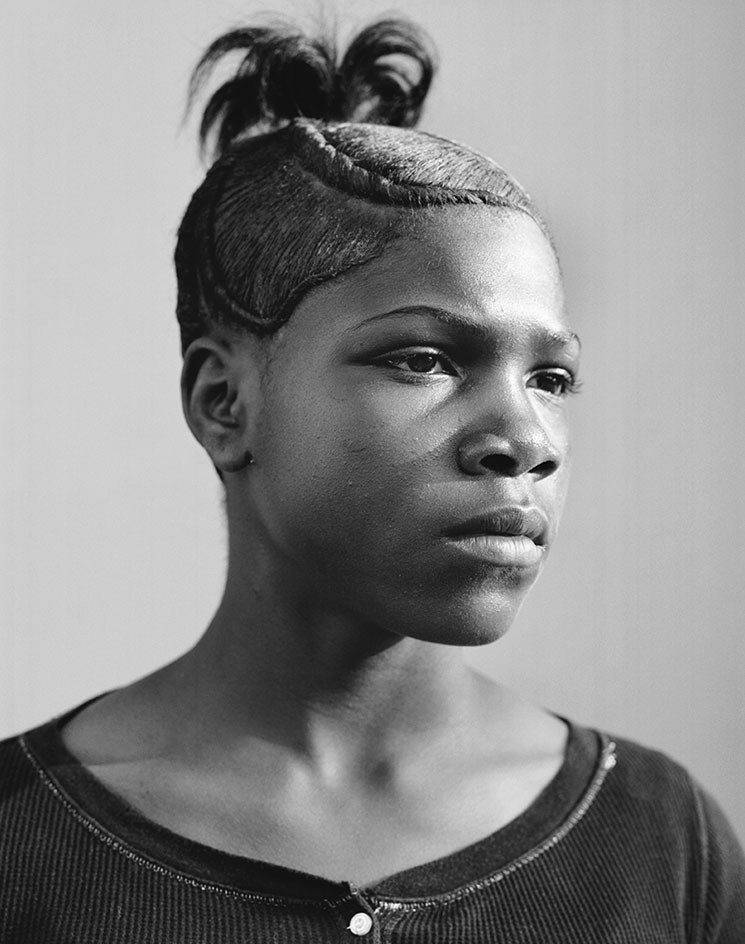

She was not naïve, but was determined tell the lives of her subjects from an angle other than the extremely one-dimensional reportage at that time. The portraits are pared down; the emotions and drama come direct from the de-sensationalized, subjects themselves rather than any attempt to focus on the background that shaped them.

Two months later, the Imperial Courts work was first presented in the Netherlands. But that was only the beginning and Lixenberg continued to visit throughout the years. ‘People started asking when I would come back to take more pictures,’ she says. I became more aware of photography as a tool to really document and preserve personal history.’

She returned to Imperial Courts with her camera in 2008 to work on a more thorough and layered documentation; this time, she began using sound and video. She started looking at the landscape and the relentless reality and unwritten rules of the still-racist society that shaped its inhabitants.

In December, her exhibition, in the same name as the book, opened at Huis Marseille in Amsterdam. Photos from the past two decades are carefully curated in the canal-house, multi-floor space. The time span between the images allow the viewer to imagine the stories that have taken place in the interim. In the attic, a 1999 Dutch television documentary of the project is shown side by side the video Lixenberg made during her October 2015 visit.

Wallpaper* Newsletter

Receive our daily digest of inspiration, escapism and design stories from around the world direct to your inbox.

Yet, it is not goodbye. The project goes on in the form of an interactive website, which allows the residents to contribute and continue writing their family’s history.

Lixenberg’s photos cover the spectrum of human failure and success, from the people who took drugs, went into gangs and eventually to prison, to those who kicked destructive habits and turned their lives around. And, too, the people just trying to live quiet lives, who were affected by the unsettled environment. Pictured: Tony’s Memorial, 2010

In 2008, Lixenberg returned to Imperial Courts with an audio recorder, began to record conversations and reactions to the photographs and the people in them, in order to capture the soundtrack of the neighbourhood.

The Charismatic China was Lixenberg’s favourite person in Imperial Courts, she vanished in 2009. Pictured: China, 1993 (†2009).

Freeway, 1993 Imperial Courts, originally quarters for World War II factory workers, is a monotonous series of two-storey housing blocks painted in pastel colours.

Spider, 1993 (†1997).

Tony Bogard, gang leader and ‘godfather’ to the community, later helped to forge a peace between the two major rival gangs. On Lixenberg’s final day in Imperial Courts in 1993, he permitted this portrait. Months later, he was killed by one of his own gang. Pictured: TB, 1993 (†1994).

Sista, 2009, Tony’s mother.

Lixenburg, today, still work only with her 4x5 large-format field camera.

Tish’s Baby Shower, 2008.

Solé, 2013.

Untitled (birthday party), 2012.

When Lixenberg returned to Imperial Courts for the last time in 2015, she finally made a photograph of that rebuilt playground where the work first really began. Pictured: Untitled, 2015.

Lixenburg says that after 22 years, Imperial Courts and its people are part of her life.

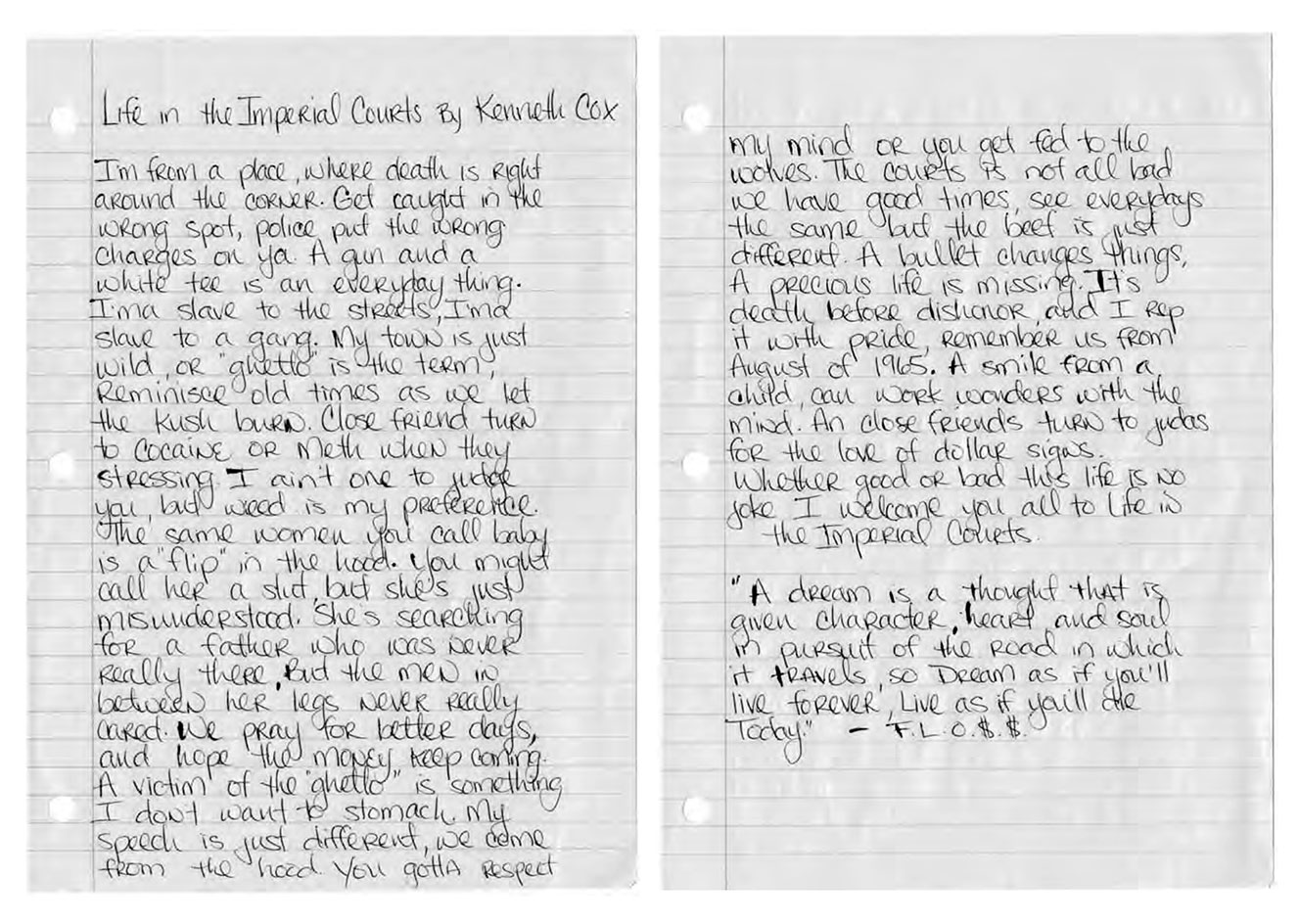

Kenneth Cox (Floss), 2015.

INFORMATION

Find out more about the Imperial Courts Project, website

’Imperial Courts 1993–2015’ is on view at Huis Marseille, Amsterdam, until 6 March 2016

ADDRESS

Keizersgracht 401, 1016 EK Amsterdam, Netherlands

Yoko Choy is the China editor at Wallpaper* magazine, where she has contributed for over a decade. Her work has also been featured in numerous Chinese and international publications. As a creative and communications consultant, Yoko has worked with renowned institutions such as Art Basel and Beijing Design Week, as well as brands such as Hermès and Assouline. With dual bases in Hong Kong and Amsterdam, Yoko is an active participant in design awards judging panels and conferences, where she shares her mission of promoting cross-cultural exchange and translating insights from both the Eastern and Western worlds into a common creative language. Yoko is currently working on several exciting projects, including a sustainable lifestyle concept and a book on Chinese contemporary design.

-

SMAC Venice hosts a substantial show about celebrated Australian modernist Harry Seidler

SMAC Venice hosts a substantial show about celebrated Australian modernist Harry SeidlerA comprehensive overview of the life and work of the late architect Harry Seidler helped inaugurate Venice’s new SMAC gallery in Piazza San Marco

-

Sex, scent and celebrity: what perfume ads of the 2000s reveal about consumer culture today

Sex, scent and celebrity: what perfume ads of the 2000s reveal about consumer culture todayIn All-American Ads of the 2000s, the latest instalment of Taschen’s book series chronicling print advertising across ten decades, a section on perfume is a striking precursor for consumerism in the age of social media

-

Shola Branson draws from the antique and modern for his must-have jewellery pieces

Shola Branson draws from the antique and modern for his must-have jewellery piecesShola Branson's jewellery in SMO gold combines a range of eclectic influences

-

Meet the duo using hair and photography as a medium to consider Africa and the African diaspora

Meet the duo using hair and photography as a medium to consider Africa and the African diaspora‘Strands & Structures’ makes its European debut at the Open Space Contemporary Art Museum in Amsterdam, exploring social and environmental issues in Accra, Ghana

-

‘The danger of AI’, photography and the future at Foam

‘The danger of AI’, photography and the future at FoamNew project ‘Photography Through the Lens of AI’ asks the big questions at Foam, Amsterdam

-

Artist Peggy Kuiper’s impactful figurative works explore her memories and emotional landscape with striking visual intensity

Artist Peggy Kuiper’s impactful figurative works explore her memories and emotional landscape with striking visual intensityPeggy Kuiper presents ‘The Conversation That Never Took Place’ at Reflex in Amsterdam, featuring over 25 new works (until 13 July)

-

Meredith Monk’s interdisciplinary art sets all the senses singing in Amsterdam show

Meredith Monk’s interdisciplinary art sets all the senses singing in Amsterdam show‘Meredith Monk: Calling’ at Oude Kerk, Amsterdam, is both a series of concerts and a deep-dive into Monk’s eclectic oeuvre

-

Heads up: art exhibitions to see in January 2024

Heads up: art exhibitions to see in January 2024Start the year right with the Wallpaper* pick of art exhibitions to see in January 2024

-

Carlijn Jacobs and Sabine Marcelis create a surreal fantasy at Foam, Amsterdam

Carlijn Jacobs and Sabine Marcelis create a surreal fantasy at Foam, AmsterdamPhotographer Carlijn Jacobs has united with Sabine Marcelis on the design of her first solo exhibition, at Foam, Amsterdam

-

Caroline Walker curates as Grimm Amsterdam explores domesticity in art

Caroline Walker curates as Grimm Amsterdam explores domesticity in artCurating ‘The Painted Room’ at Grimm Amsterdam, Caroline Walker explores the intimacy of interiors

-

Drift Museum, a blockbusting experiential space, is set to open in Amsterdam in 2025

Drift Museum, a blockbusting experiential space, is set to open in Amsterdam in 2025Drift Museum is a collaboration between art duo Drift – aka Lonneke Gordijn and Ralph Nauta – and entrepreneur Eduard Zanen