Paul Strand: an American enigma and his portrait of an Italian village

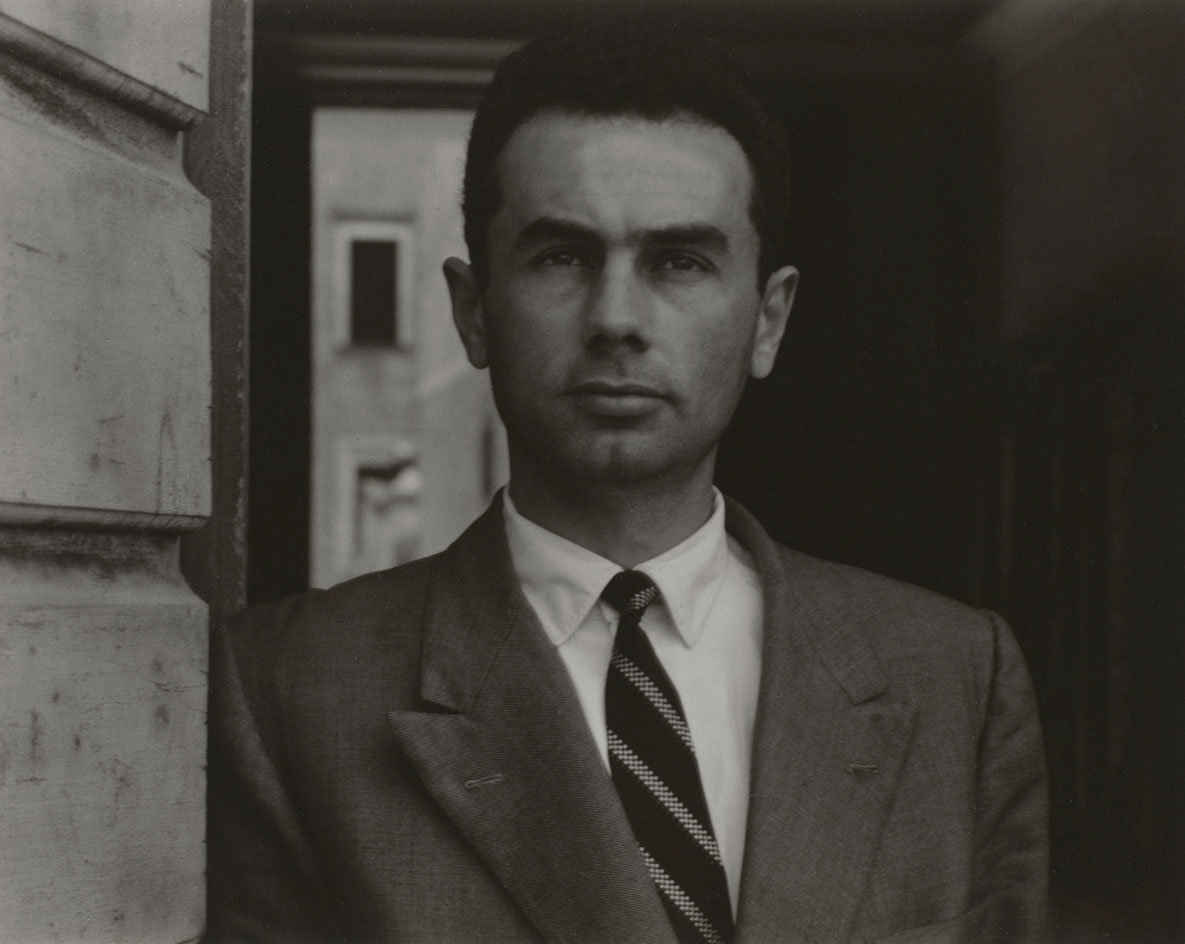

Photographer, filmmaker, political activist, husband, enigma, collaborator, and pioneer: these are simply a handful of the words that could be used to describe Paul Strand (1870–1976). Together with Edward Weston and his mentor Alfred Stieglitz, he elevated modernist photography – in particular, ‘straight photography’ – to a fine art form in the 20th century.

Born in New York to a Jewish family, Strand was 12 when his father gifted him a Brownie camera. He did not, however, take to photography immediately, distracted by the advent of automobiles on the city’s streets and other diversions. In 1904, his parents enrolled him in a public school where he signed up for an extracurricular photography course led by one of the science teachers, and was eventually introduced to Stieglitz’s art gallery 291 (and later, the man himself).

From then on Strand was consumed, photographing everything from architecture to street portraiture, landscapes and still lifes (these with an appealingly Picasso bent). Inspired by Edgar Lee Masters’ Spoon River Anthology, he soon became obsessed with the idea of creating a book about a village to ‘find and show many of the elements that make this village a particular place where particular people live and work.’

In 1949, Strand met his third wife and fellow photographer, Hazel Kingsbury. They married two years later and departed for France, intending to stay only for a few months. There Strand encountered the poet Claude Roy and together they published a book documenting rural France, which would prove to be a springboard for his next work.

Strand befriended the Italian screenwriter Cesare Zavattini in Perugia. A mutual friend ‘helped them get better acquainted’, and from their friendship a collaborative project was born – Strand would document Zavattini’s hometown of Luzzara, a small Italian village in the Reggio Emilia province. Zavattini brokered shoots with the villagers on Strand’s behalf and together they composed a striking visual and literary chronicle of Luzzara, Un Paese: Portrait of an Italian Village, published in 1955.

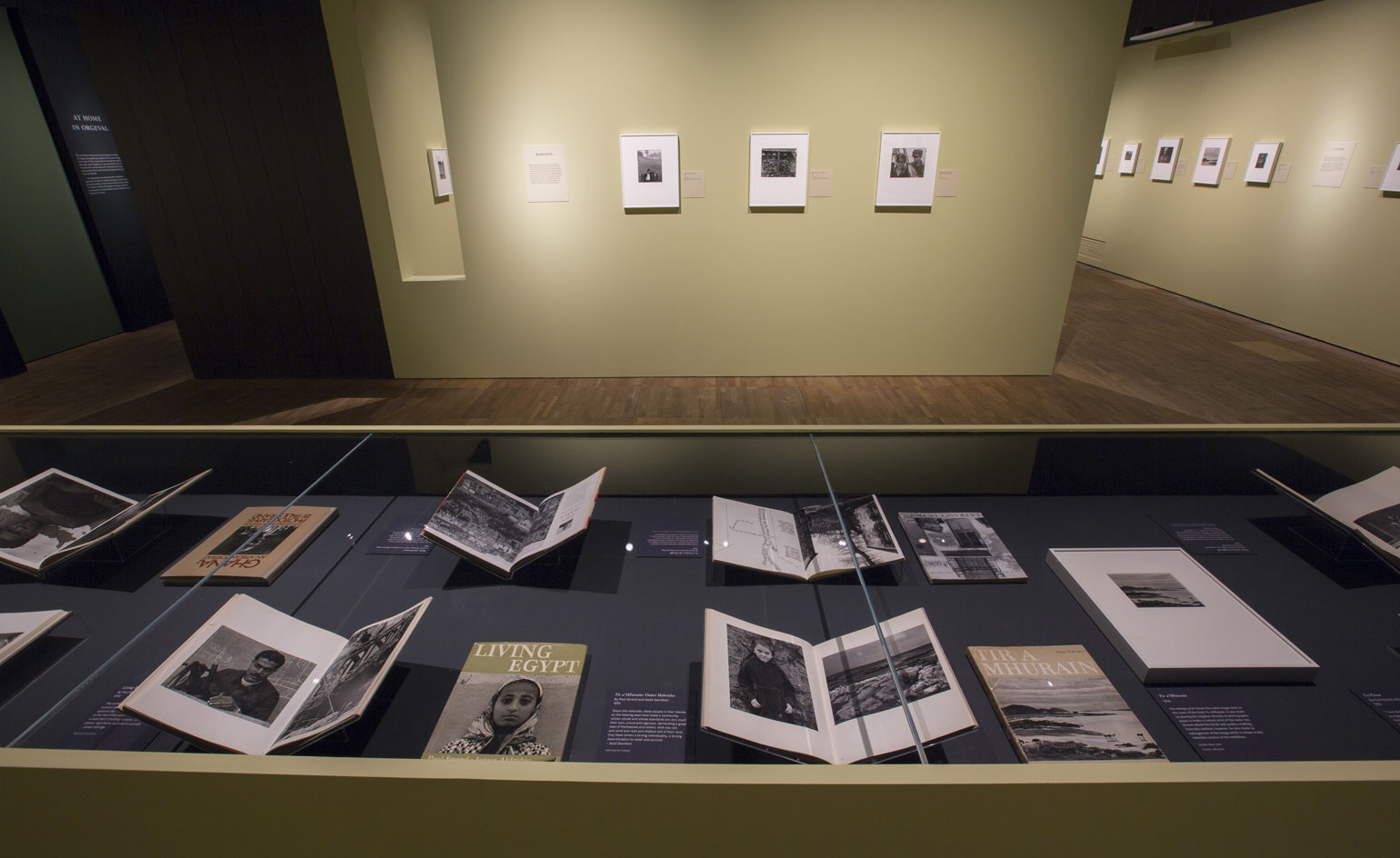

These images are now on view as part of a major new retrospective, ‘Paul Strand: Photography and Film for the 20th Century’, at the Victoria and Albert Museum in London exploring his vast oeuvre. The show opens with photographs from his native New York in the 1910s, and spans work from his travels in Mexico, Ghana, the Hebrides, New England and beyond – but it is Un Paese that particularly shines amongst his endlessly fascinating subjects.

The most decisive photograph in the series (and suitably the book’s cover) is The Family, a powerful tableau of an Italian widow and five of her eight sons. Four of matriarch Anna Lusetti’s children had died infancy – she spoke of the physical abuse suffered by her husband at the hands of ‘unidentified political assailants’. Her English-speaking son, Valentino, also served as Strand's translator and fixer.

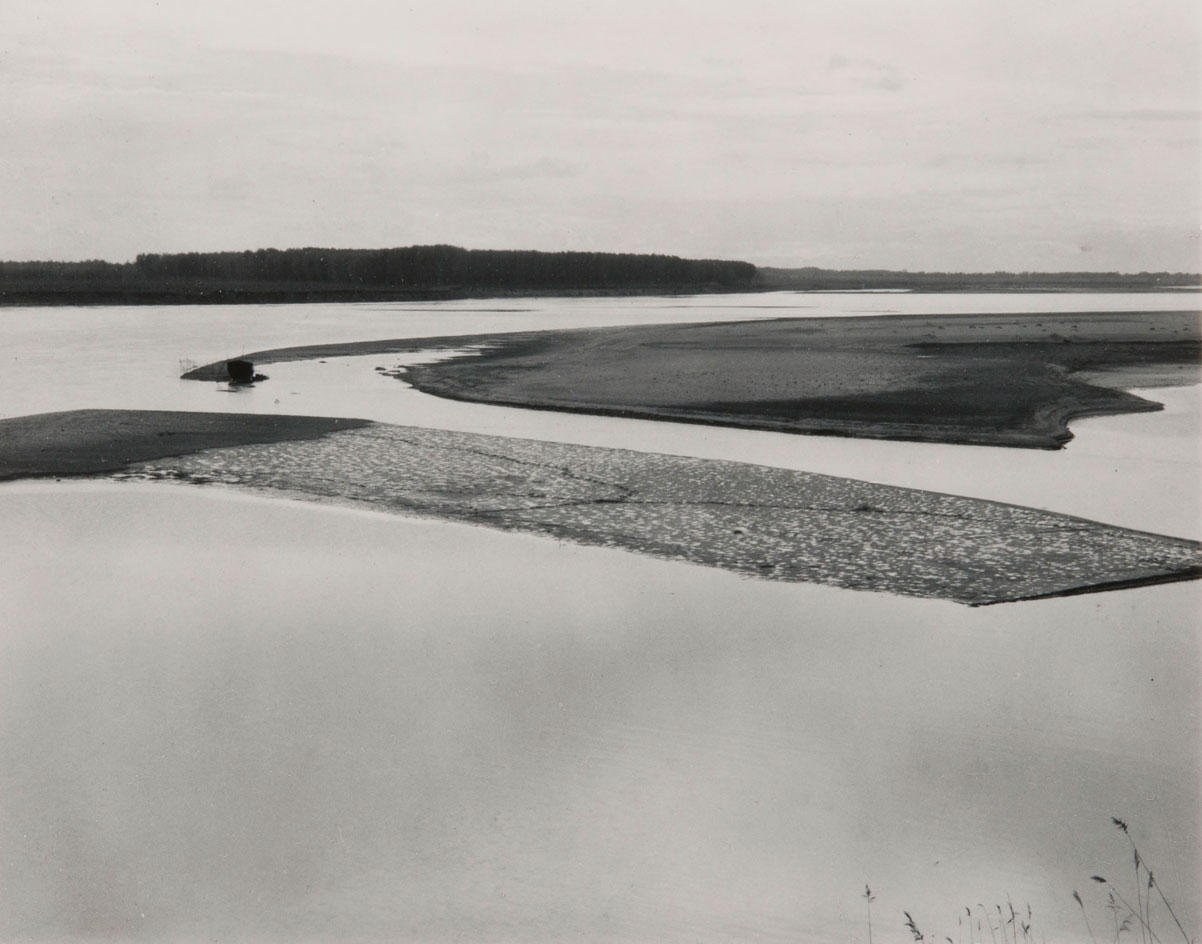

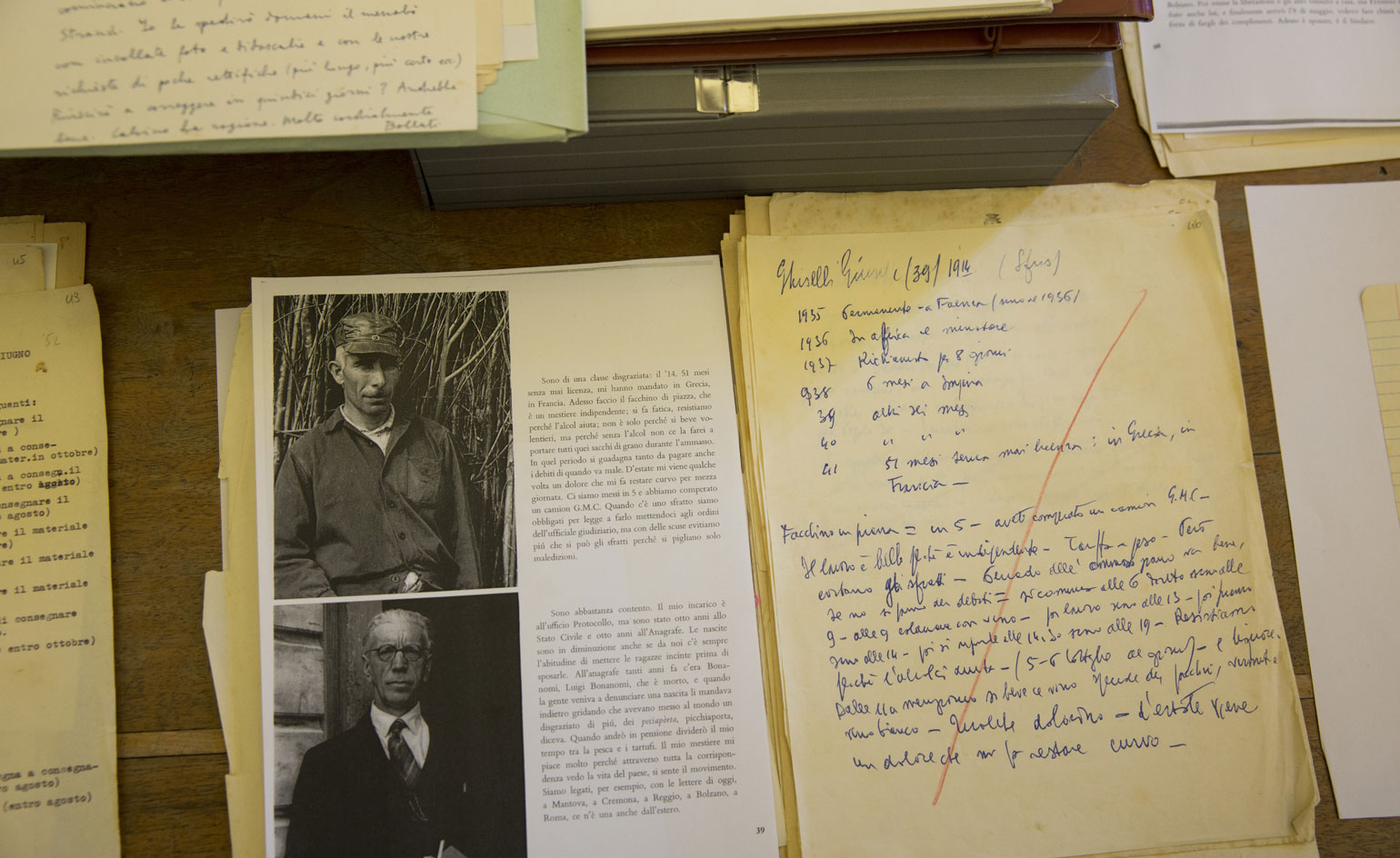

‘Strand was reserved, but he was also human,’ wrote Zavattini a few years after the photographer’s death. ‘In an almost biblical way, he always journeyed down from the heights into the valley, losing himself among configurations of dust and human shapes.’ Even in images absent of his fellow townspeople, Zavattini noted that ‘the landscape itself breathes the evidence of human effort’. The pair never worked directly together, but a voluminous collection of letters, postcards, notebooks and correspondence detail their fastidious research.

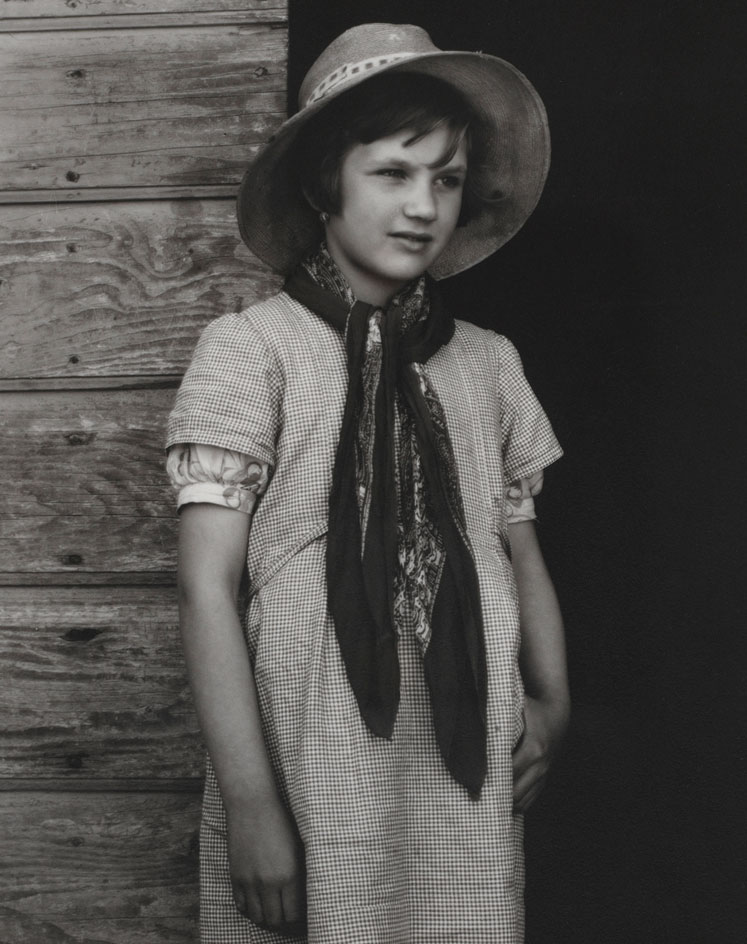

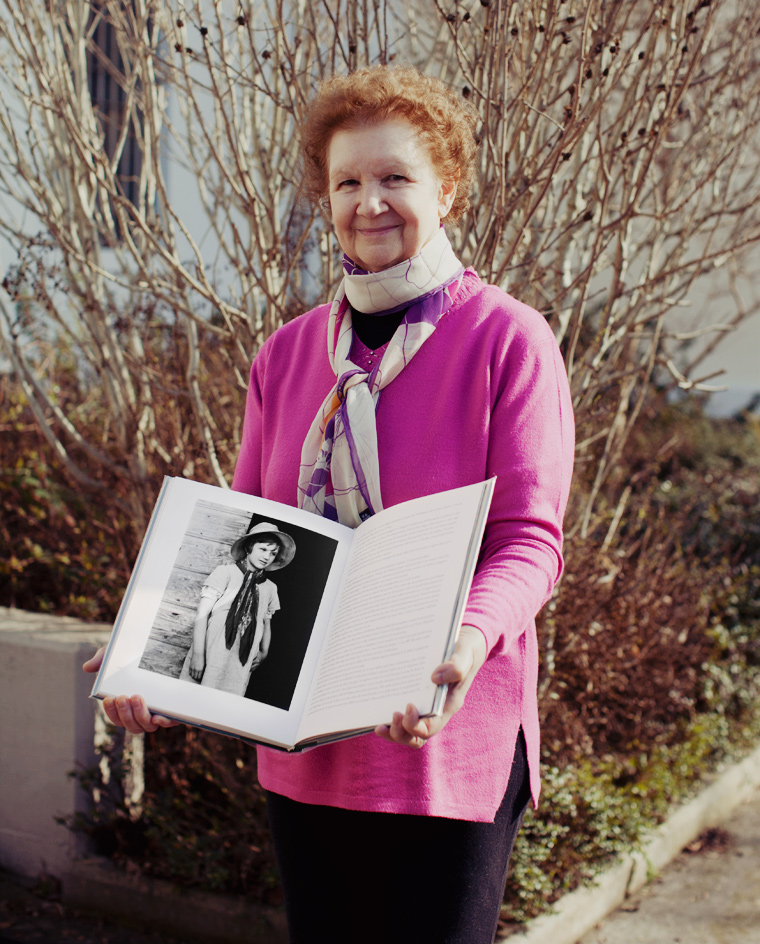

Luzzara native Angela Secchi is one of the few people photographed for Un Paese still alive today. ‘I was scared by Strand because he was a very serious man who never smiled,’ recalls Secchi, now 73. She was nine years old and it was the first time she had ever seen a camera. Strand, she says, was impressed by her red hair and fair skin. Her aunt wanted her to wear a nice dress but Strand insisted on a threadbare smock along with her uncle’s hat. He chose a doorway and it was over quickly.

Strand had no interest in glossing over the prevailing poverty in postwar Italy, even if his images today might seem infused with an inherently provincial and romantic quality. He was exacting and meticulous, shooting on a large format camera. Solemn and self-contained almost to a fault, Strand rarely spoke to his subjects. He was particular about the size and shape of prints, even modifying his camera to take off a ¼ inch from the frame. In a letter, he mentioned he abhorred square photographs – although his wife Hazel often shot in this format.

Hazel’s photographs of Luzzara were only discovered in the 1980s and they offer a buoyant counterpoint to the sternness of Strand’s compositions (the Cultural Center Zavattini has several of her work in its archive). She, too, photographed the Lusetti family, although they appear animated, embracing each other with a lively warmth as they smile resiliently for her. She was the antithesis to her husband: a silent partner but, like Zavattini, no less integral to Strand’s creative process.

Little has changed in Luzzara since Un Paese was published. Many of the locations and details in Strand’s photographs – the village square, the smattering of bicycles – exist virtually unchanged. It’s as though Strand stopped time with his camera in 1952. Un Paese foreshadowed Strand’s future work, and he would continue in very much the same vein, immersing himself in far-flung locales and documenting its inhabitants.

The V&A exhibition concludes with work from Strand’s final years. He had spent the last 26 years of his life in Orgeval, France, with Hazel; she restored the garden, while he documented its growth over two decades. ‘Almost all things of the world have their own character,’ Strand once said. ‘I think that what exists outside the artist is much more important than his imagination. The world outside is inexhaustible. What a person feels about life is not inexhaustible at all.’ It seems Strand never tired of the world he so tirelessly photographed up until his death.

The exhibition spans Strand’s vast oeuvre, opening with photographs from his native New York in the 1910s.

Strand travelled extensively, producing both photographs and photobooks of his travels through Mexico, Ghana, the Hebrides, New England, Egypt and beyond.

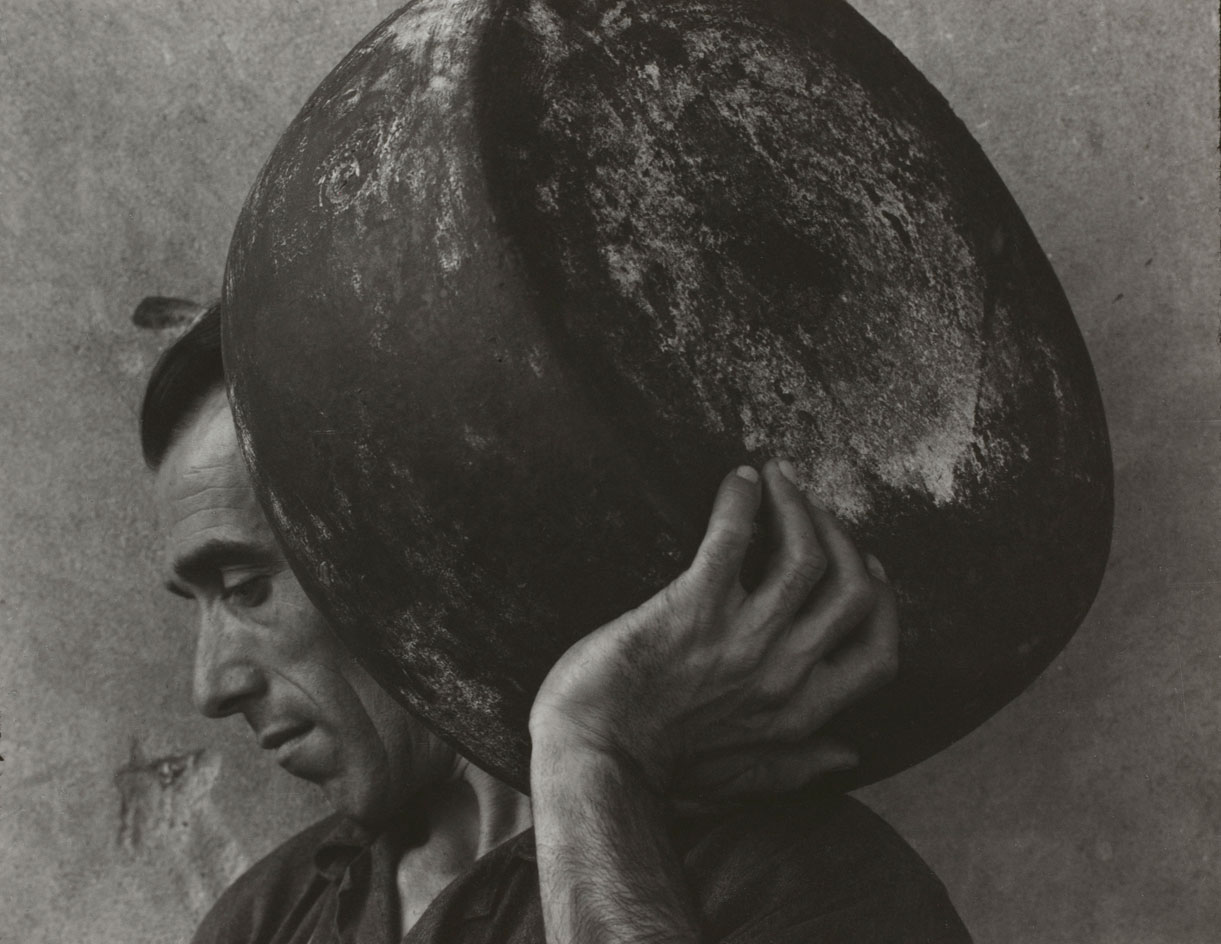

He became obsessed with documenting a village, eventually finding his ‘muse’ in Luzzara, a small Italian town in the province of Reggio Emilia. Here, he teamed up with local writer Cesare Zavattini to create Un Paese: Portrait of an Italian Village, published in 1955. Pictured: Market Day, 1953.

The most decisive photograph in the series (and the book’s cover) is The Family, 1953, a powerful tableau of an Italian widow and five of her eight sons.

Hallway, 1953.

Luzzara local Angela Secchi was nine years old when Strand photographed her. Pictured: Farmer’s Daughter, 1953.

Now 73, Secchi, pictured here holding her portrait by Strand, is one of the few people photographed for Un Paese still alive today. ‘I was scared by Strand because he was a very serious man who never smiled,’ she recalls.

Strand photographed the locals craftsmen intensively, including this striking image of a parmesan cheesemaker.

Even in images absent of his fellow townspeople, Zavattini noted that ‘the landscape itself breathes the evidence of human effort’. Pictured: Sand Flats, The Po, 1953.

Zavattini and Strand never worked directly together, but a voluminous collection of letters, postcards, notebooks and correspondence detail their fastidious research. Pictured here, Zavattini’s interview notes.

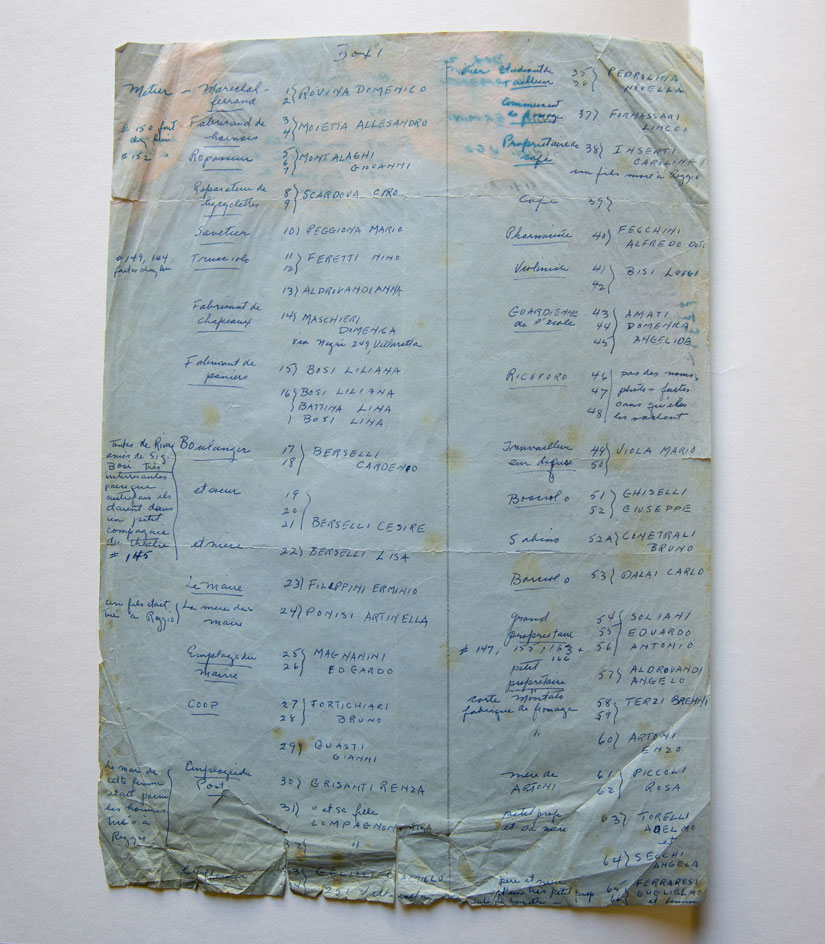

List of people photographed by Strand in Luzzara in 1953, compiled by his wife Hazel.

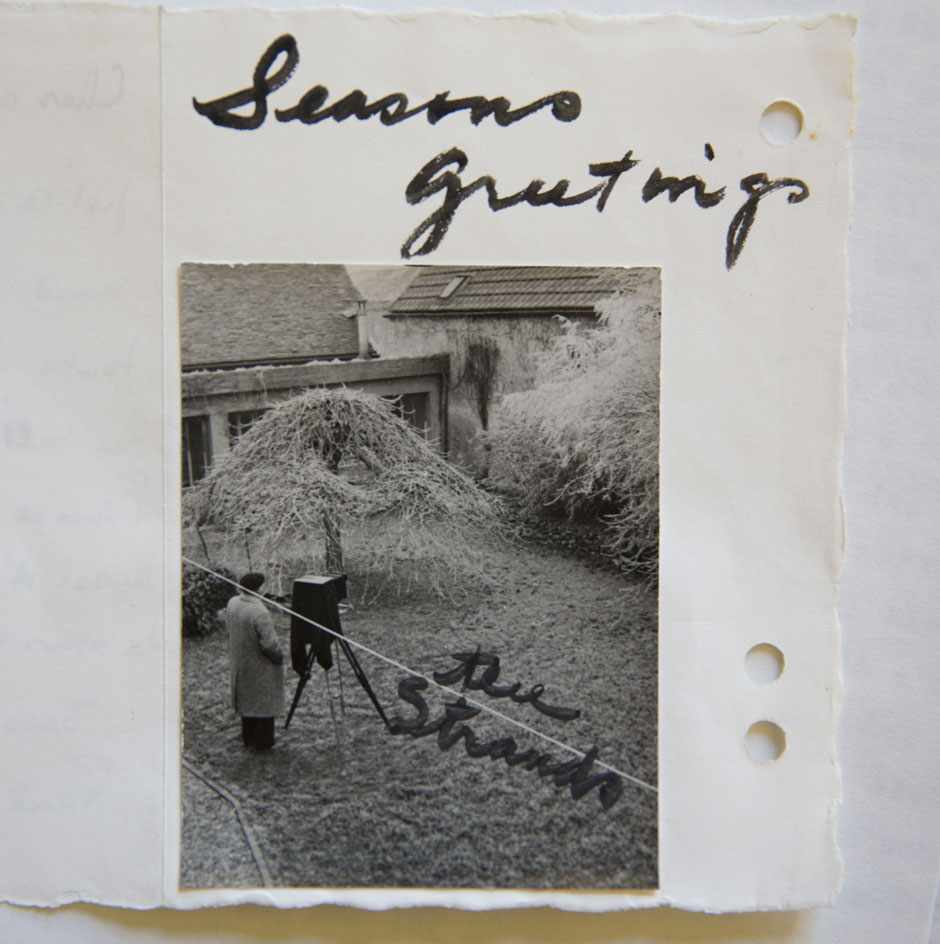

Christmas card sent to Zavattini from the Strands, 1958. Many of these objects are held in the Biblioteca Panizzi in Reggio Emilia.

Workers’ Bicycles, 1953.

The Mayor, 1953.

Place to Meet, 1953.

Little has changed in Luzzara since Un Paese was published. Many of the backdrops and details in Strand’s photographs exist virtually unchanged.

Luzzara’s locals still gather to meet in the village square and the arcades.

Arcades, 1953.

Card Players, Cafe, 1953.

Installation view of ‘Paul Strand: Photography and Film for the 20th Century’.

Akeley motion picture camera, circa 1920. Strand bought this camera in 1922 and used it to make all his subsequent films. It was revolutionary for its capacity to tilt (up and down) and pan (left to right) simultaneously.

The V&A exhibition concludes with work from Strand’s final years. He had spent the last 26 years of his life in Orgeval, France, with Hazel; she restored the garden, while he documented its growth over two decades.

INFORMATION

‘Paul Strand: Photography and Film for the 20th Century’ runs until 3 July. Supported by the American Friends of the V&A. For more information, visit the Victoria and Albert Museum website

ADDRESS

Cromwell Rd

London SW7

Wallpaper* Newsletter

Receive our daily digest of inspiration, escapism and design stories from around the world direct to your inbox.

-

The Lighthouse draws on Bauhaus principles to create a new-era workspace campus

The Lighthouse draws on Bauhaus principles to create a new-era workspace campusThe Lighthouse, a Los Angeles office space by Warkentin Associates, brings together Bauhaus, brutalism and contemporary workspace design trends

By Ellie Stathaki

-

Extreme Cashmere reimagines retail with its new Amsterdam store: ‘You want to take your shoes off and stay’

Extreme Cashmere reimagines retail with its new Amsterdam store: ‘You want to take your shoes off and stay’Wallpaper* takes a tour of Extreme Cashmere’s new Amsterdam store, a space which reflects the label’s famed hospitality and unconventional approach to knitwear

By Jack Moss

-

Titanium watches are strong, light and enduring: here are some of the best

Titanium watches are strong, light and enduring: here are some of the bestBrands including Bremont, Christopher Ward and Grand Seiko are exploring the possibilities of titanium watches

By Chris Hall

-

The UK AIDS Memorial Quilt will be shown at Tate Modern

The UK AIDS Memorial Quilt will be shown at Tate ModernThe 42-panel quilt, which commemorates those affected by HIV and AIDS, will be displayed in Tate Modern’s Turbine Hall in June 2025

By Anna Solomon

-

Meet the Turner Prize 2025 shortlisted artists

Meet the Turner Prize 2025 shortlisted artistsNnena Kalu, Rene Matić, Mohammed Sami and Zadie Xa are in the running for the Turner Prize 2025 – here they are with their work

By Hannah Silver

-

‘Humour is foundational’: artist Ella Kruglyanskaya on painting as a ‘highly questionable’ pursuit

‘Humour is foundational’: artist Ella Kruglyanskaya on painting as a ‘highly questionable’ pursuitElla Kruglyanskaya’s exhibition, ‘Shadows’ at Thomas Dane Gallery, is the first in a series of three this year, with openings in Basel and New York to follow

By Hannah Silver

-

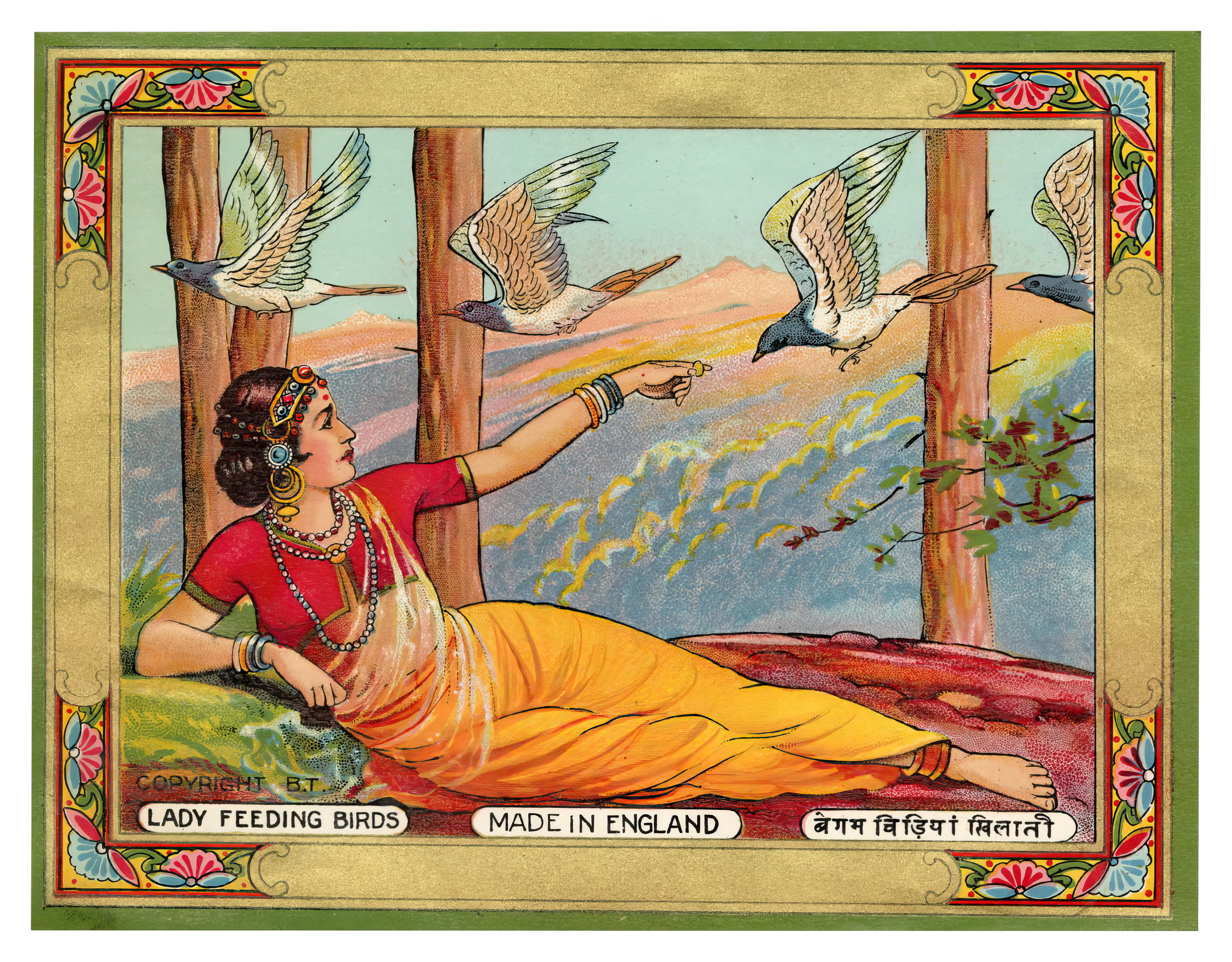

The art of the textile label: how British mill-made cloth sold itself to Indian buyers

The art of the textile label: how British mill-made cloth sold itself to Indian buyersAn exhibition of Indo-British textile labels at the Museum of Art & Photography (MAP) in Bengaluru is a journey through colonial desire and the design of mass persuasion

By Aastha D

-

Artist Qualeasha Wood explores the digital glitch to weave stories of the Black female experience

Artist Qualeasha Wood explores the digital glitch to weave stories of the Black female experienceIn ‘Malware’, her new London exhibition at Pippy Houldsworth Gallery, the American artist’s tapestries, tuftings and videos delve into the world of internet malfunction

By Hannah Silver

-

Ed Atkins confronts death at Tate Britain

Ed Atkins confronts death at Tate BritainIn his new London exhibition, the artist prods at the limits of existence through digital and physical works, including a film starring Toby Jones

By Emily Steer

-

Tom Wesselmann’s 'Up Close' and the anatomy of desire

Tom Wesselmann’s 'Up Close' and the anatomy of desireIn a new exhibition currently on show at Almine Rech in London, Tom Wesselmann challenges the limits of figurative painting

By Sam Moore

-

A major Frida Kahlo exhibition is coming to the Tate Modern next year

A major Frida Kahlo exhibition is coming to the Tate Modern next yearTate’s 2026 programme includes 'Frida: The Making of an Icon', which will trace the professional and personal life of countercultural figurehead Frida Kahlo

By Anna Solomon