Performance art: a new Alexander Calder retrospective opens at Tate Modern

As Achim Borchardt-Hume, director of exhibitions at Tate Modern, points out, an Alexander Calder mobile has long been an almost essential fitting for the modernist dream home; in renders as much as the realised, where they are instantly recognisable, and bring colour and movement to hypothetically elegant, airy spaces. Architects love Calder as he loved them (he knew all the important ones) because he created wonderful objects that move in space and make spaces feel more wonderful. (His mobiles are also as much about what isn’t there – their transparency and fluttering lightness – which also appeals to modernist architects.)

Of course, its not just architects. Everyone loves a Calder. The Calder mobile is the friendly, accessible, unpretentious and playful face of modernism. There is nothing difficult about a Calder. And, as happens, Calder’s reputation has suffered from this warm over familiarity.

'Alexander Calder: Performing Sculpture', a new show at Tate Modern and the largest ever UK show of Calder’s works, reminds us how serious Calder was about his art. And how, as it evolved over time, much Calder removed to get what he wanted.

Sandy Rower, Calder’s grandson and president of the Calder Foundation, was in London for the opening of the show – and was quick to point out that this wasn’t a simple retrospective. The show starts with Calder’s early output from his time in 1920s Paris and finishes with works from the early 1950s. Calder carried on working, and at a good pace, for almost three decades, during which his work got bigger and more ambitious (the Tate Modern show doesn’t include any of the more monumental stabiles that architects loved to put in their modernist plazas). But it was in these three decades that Calder got the essentials right.

The show begins with his wire sculptures, clever 3-D sketches including one of Josephine Baker and others of the circus performers and acrobats who were a continuing fascination to the artist.

By the 1930s, and following a career-changing visit to the studio of Piet Mondrian – 'it was like a baby being slapped to make its lungs stop working,' Calder said – he had moved on to mechanised ‘mobiles’, a term coined by his friend Marcel Duchamp. (When A Universe, amongst the best known of these motorised pieces, was first exhibited at MoMA, Einstein apparently spent forty minutes watching it complete its full cycle of movements).

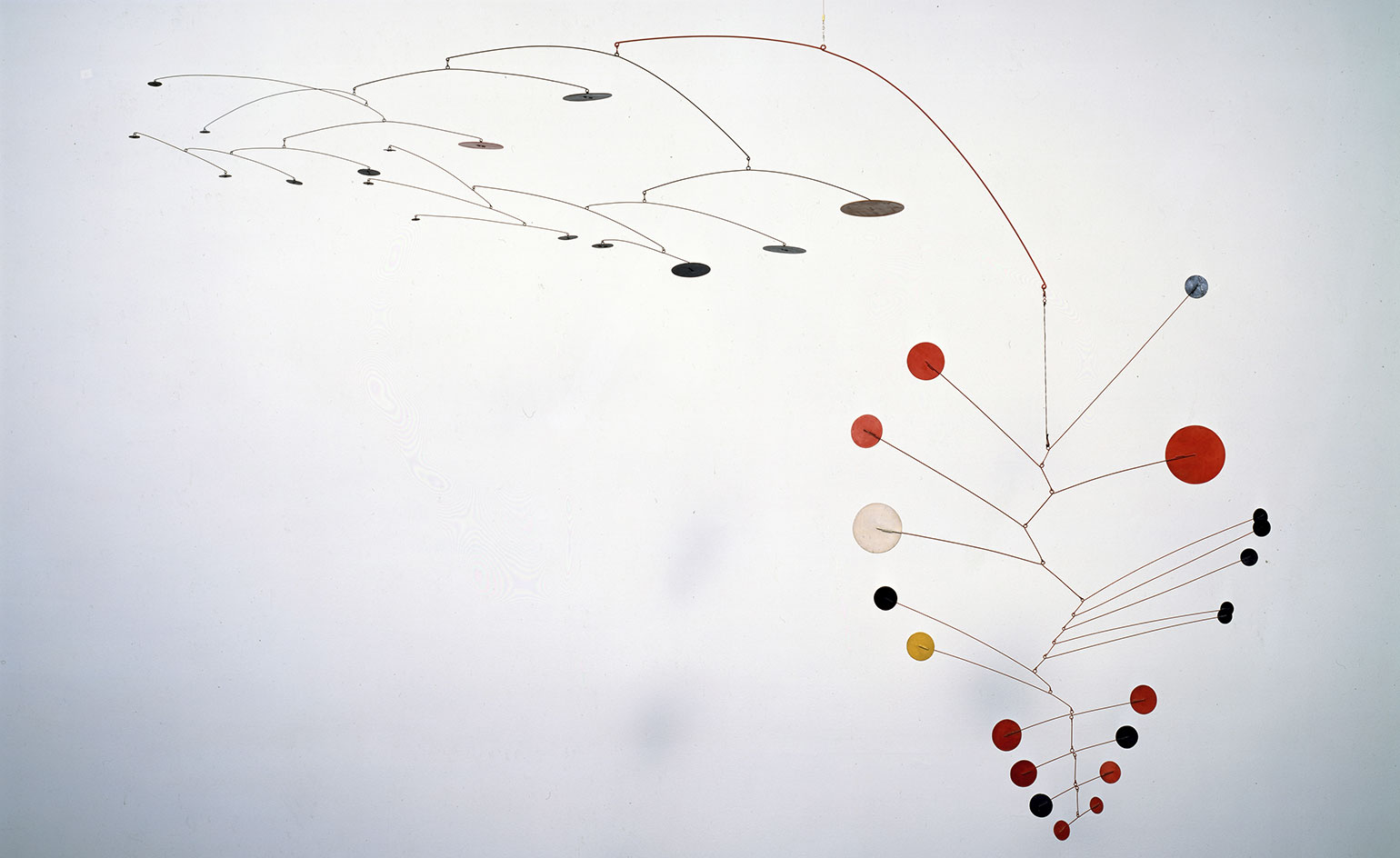

Later in the decade he would lose the motors and relay on precise balance and air flow to create movement. These fluid abstracts, constantly shifting and ‘performing’, were a radical break from the past, taking sculpture to entirely new places – Calder was from a long line of figurative sculptures so he knew where he was heading away from. These pieces – Morning Star, Constellation, Vertical Foliage, Gamma, Snow Flurry are all on show – are cosmic systems or natural events. 'The idea of detached bodies floating in space, of different sizes and densities, some at rest, while others move in particular manners, seems to me the ideal source of form,' Calder said.

The show ends with Black Widow, a 3.5m mobile donated to the Institute of Architects of Brazil in São Paulo in 1948, while Calder was travelling and exhibiting in Brazil.

Calder’s influence on young Brazilian artists of the time, such as Lygia Clark and Hélio Oiticica, is obvious. And Calder remains an influence. Witness Sarah Sze’s marvelous mobiles, shown at Victoria Miro this year. Sze is just one the artists to enjoy a residency at the Atelier Calder, built by Calder near Saché in France in 1962. Run by Rower and the Calder Foundation. It offers artists the chance to work in what was Calder’s huge, light-filled studio, live in the Calder residence and enjoy the views across the Loire Valley.

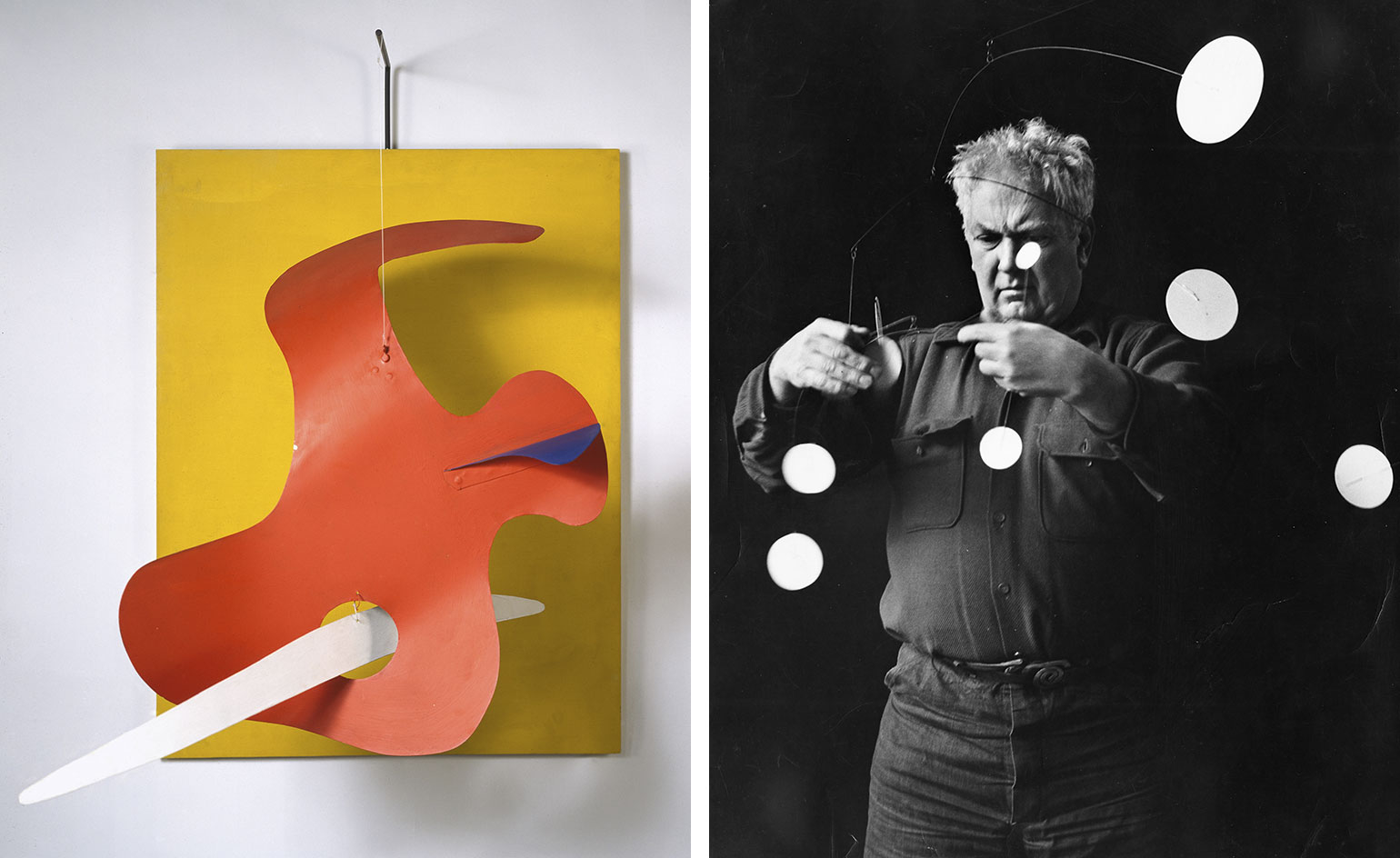

The show is titled ’Alexander Calder: Performing Sculpture’ and is the largest ever UK show of Calder’s works. Left: Form Against Yellow (Yellow Panel), 1936. Right: Alexander Calder with Snow Flurry I (1948), 1952.

The show starts with Calder’s early output from his time in 1920s Paris and finishes with works from the early 1950s. Pictured: Black Frame, 1934.

Installation shot of Calder’s mobiles and stabiles Courtesy: Calder Foundation, New York / DACS, London

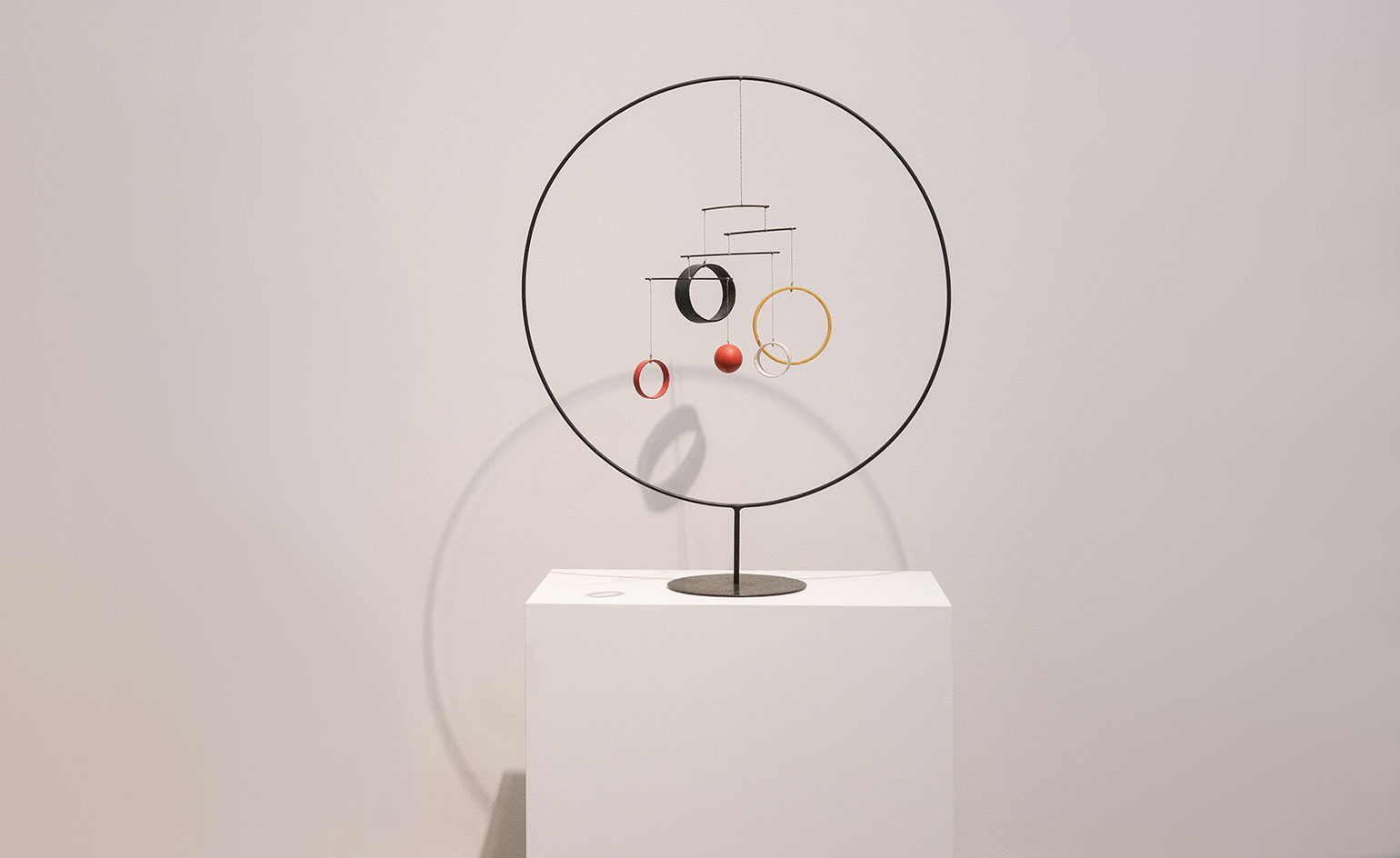

Left: Untitled, c.1934. Right: Untitled, c.1937.

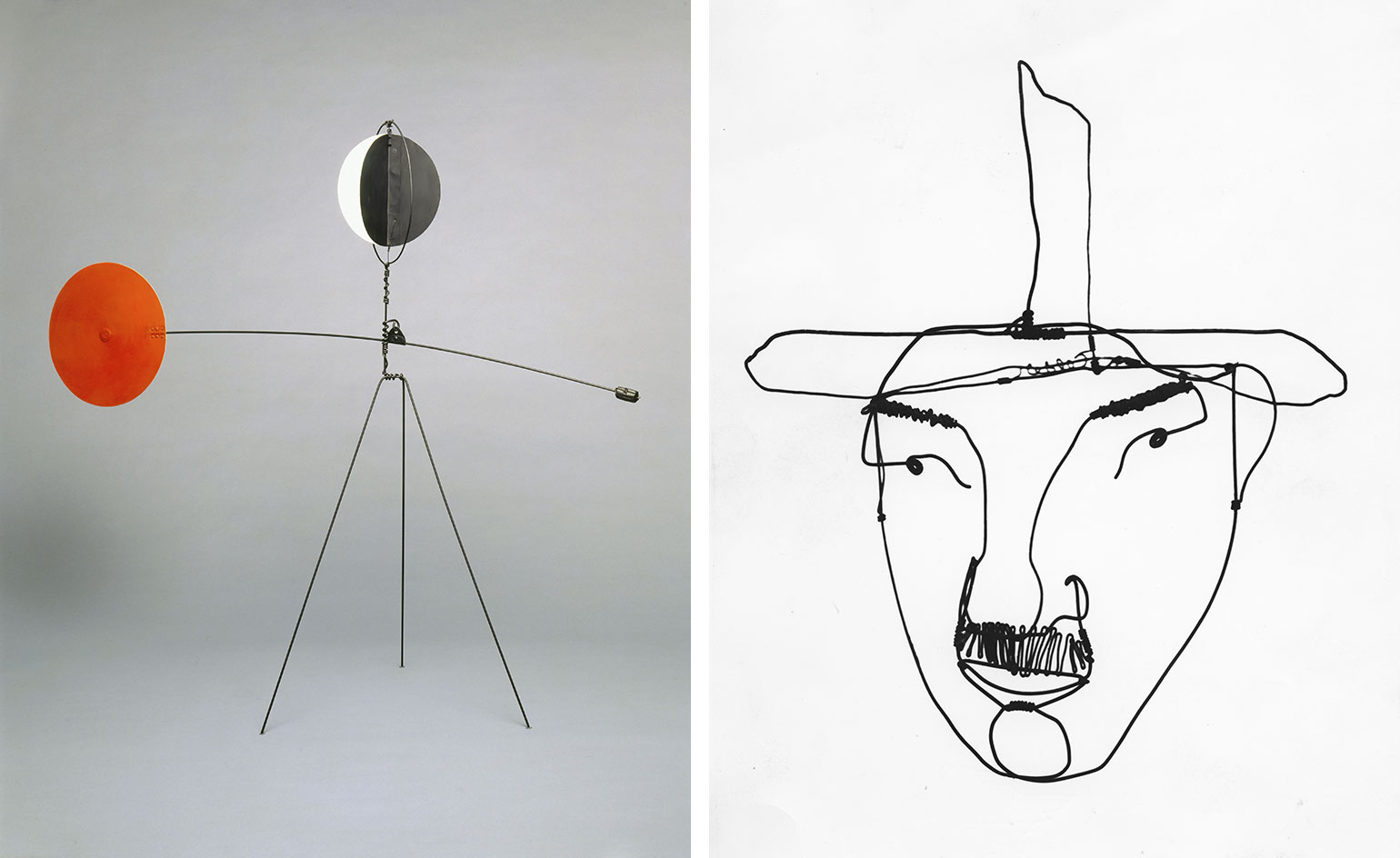

The show begins with his wire sculptures, clever 3-D sketches including one of Josephine Baker and others of the circus performers and acrobats who were a continuing fascination to the artist. Pictured left: Two Acrobats, 1929. Courtesy Menil Collection. Right: Small Sphere and Heavy Sphere, 1932–33.

Everyone loves a Calder. The Calder mobile is the friendly, accessible, unpretentious and playful face of modernism. Pictured: Gamma, 1947.

Installation shots of Calder’s wire portraits (Joan Miró, 1929, Fernand Léger, 1930, and Varése, c.1930). Courtesy: Calder Foundation, New York / DACS, London

Installation shot of Untitled, c.1934 Courtesy: Calder Foundation, New York / DACS, London

Later in his career, Calder would relay on precise balance and air flow to create movement. Pictured: Triple Gong, c.1948.

Vertical Foliage, 1941.

Installation shot of Calder’s panel works, which have been reunited for the first time (pictured here is Blue Panel, 1936) Courtesy: Calder Foundation, New York / DACS, London

There is nothing difficult about a Calder. And, as happens, Calder’s reputation has suffered from this warm over familiarity. Pictured left: Red and Yellow Vane, 1934. Right: Fernand Léger, c.1930. Private collection

Installation shot of Black Widow, c.1948. Courtesy: Calder Foundation, New York / DACS, London

Untitled maquette for 1939 New York World’s Fair, 1938

INFORMATION

’Alexander Calder: Performing Sculpture’ is on view until 3 April 2016. For more information, visit Tate Modern’s website

ADDRESS

Tate Modern

Bankside

London, SE1 9TG

Wallpaper* Newsletter

Receive our daily digest of inspiration, escapism and design stories from around the world direct to your inbox.

-

A Xingfa cement factory’s reimagining breathes new life into an abandoned industrial site

A Xingfa cement factory’s reimagining breathes new life into an abandoned industrial siteWe tour the Xingfa cement factory in China, where a redesign by landscape specialist SWA Group completely transforms an old industrial site into a lush park

By Daven Wu

-

Put these emerging artists on your radar

Put these emerging artists on your radarThis crop of six new talents is poised to shake up the art world. Get to know them now

By Tianna Williams

-

Dining at Pyrá feels like a Mediterranean kiss on both cheeks

Dining at Pyrá feels like a Mediterranean kiss on both cheeksDesigned by House of Dré, this Lonsdale Road addition dishes up an enticing fusion of Greek and Spanish cooking

By Sofia de la Cruz

-

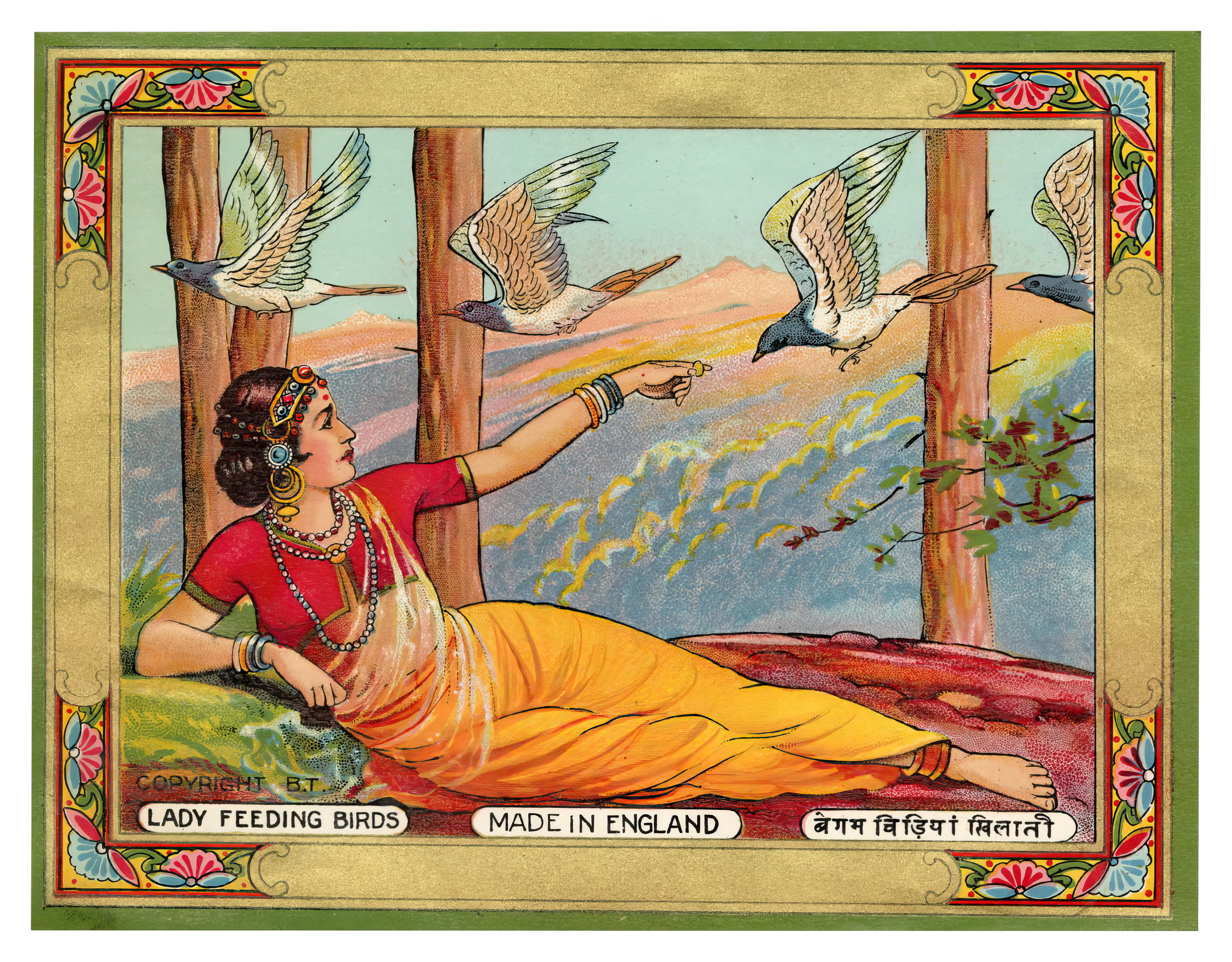

The art of the textile label: how British mill-made cloth sold itself to Indian buyers

The art of the textile label: how British mill-made cloth sold itself to Indian buyersAn exhibition of Indo-British textile labels at the Museum of Art & Photography (MAP) in Bengaluru is a journey through colonial desire and the design of mass persuasion

By Aastha D

-

Ed Atkins confronts death at Tate Britain

Ed Atkins confronts death at Tate BritainIn his new London exhibition, the artist prods at the limits of existence through digital and physical works, including a film starring Toby Jones

By Emily Steer

-

A major Frida Kahlo exhibition is coming to the Tate Modern next year

A major Frida Kahlo exhibition is coming to the Tate Modern next yearTate’s 2026 programme includes 'Frida: The Making of an Icon', which will trace the professional and personal life of countercultural figurehead Frida Kahlo

By Anna Solomon

-

From counter-culture to Northern Soul, these photos chart an intimate history of working-class Britain

From counter-culture to Northern Soul, these photos chart an intimate history of working-class Britain‘After the End of History: British Working Class Photography 1989 – 2024’ is at Edinburgh gallery Stills

By Tianna Williams

-

‘Leigh Bowery!’ at Tate Modern: 1980s alt-glamour, club culture and rebellion

‘Leigh Bowery!’ at Tate Modern: 1980s alt-glamour, club culture and rebellionThe new Leigh Bowery exhibition in London is a dazzling, sequin-drenched look back at the 1980s, through the life of one of its brightest stars

By Amah-Rose Abrams

-

Wallpaper* Design Awards 2025: Tate Modern’s cultural shapeshifting takes the art prize

Wallpaper* Design Awards 2025: Tate Modern’s cultural shapeshifting takes the art prizeWe sing the praises of Tate Modern for celebrating the artists that are drawn to other worlds – watch our video, where Wallpaper’s Hannah Silver gives the backstory

By Hannah Silver

-

Surrealism as feminist resistance: artists against fascism in Leeds

Surrealism as feminist resistance: artists against fascism in Leeds‘The Traumatic Surreal’ at the Henry Moore Institute, unpacks the generational trauma left by Nazism for postwar women

By Katie Tobin

-

Looking forward to Tate Modern’s 25th anniversary party

Looking forward to Tate Modern’s 25th anniversary partyFrom 9-12 May 2025, Tate Modern, one of London’s most adored art museums, will celebrate its 25th anniversary with a lively weekend of festivities

By Smilian Cibic