For these female photographers, the body is a tool of political dissent

The work of Liliana Maresca and Gundula Schulze Eldowy, who both lived in political turmoil, was celebrated at this year’s Artissima art fair in Turin. Discover their work here

Born just three years apart on opposite sides of the globe, Liliana Maresca and Gundula Schulze Eldowy were both entered into worlds of political turmoil. Maresca (b. 1951, Avellaneda, Argentina), under the fascistic rule of General Juan Perón (followed by military dictatorship in 1976), and Eldowy (b. 1954, Erfurt, Germany), in GDR controlled East Germany, behind the Iron Curtain. Heavily policed and creatively stifling, these environments nonetheless fuelled the photography of both women, whose trailblazing practices connected under the same roof at this year’s Artissima art fair in Turin.

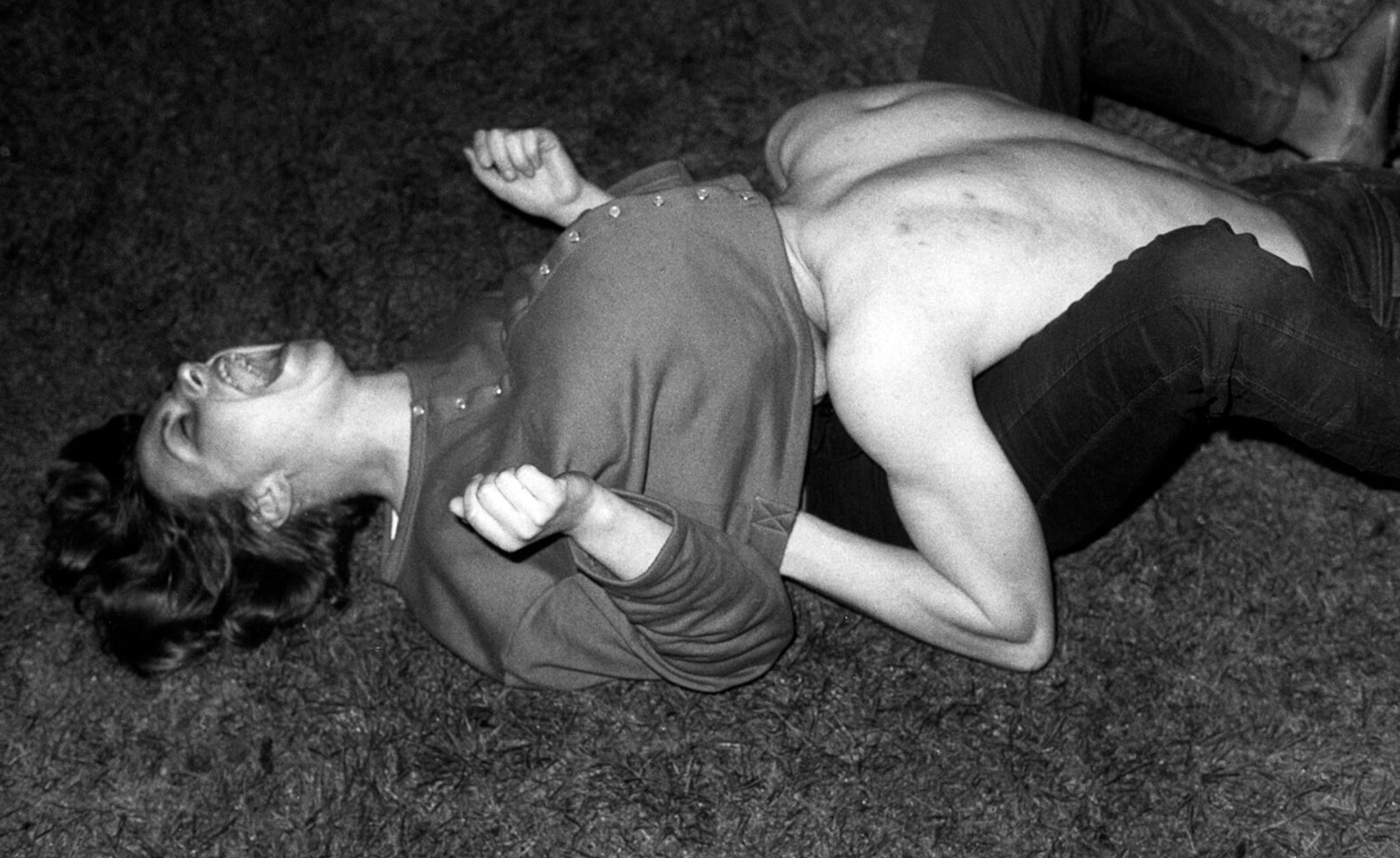

A multidisciplinary artist who made sculpture, performance and installation as well as photography, Maresca was the figurehead of an underground collective of Buenos Aires artists that sprang to life following the end of military dictatorship in 1983. Like the rest of her eclectic practice, Maresca’s photography was an act of social and political rebellion, often using her own nude body in performative self-portraits that defied traditional feminine expectations and years of state censorship.

LILIANA MARESCA Untitled. Public image - High political spheres, Costanera Sur, Buenos Aires, Photoperformance, Photography by Ludmila 1993. Courtesy Rolf Art, Buenos Aires

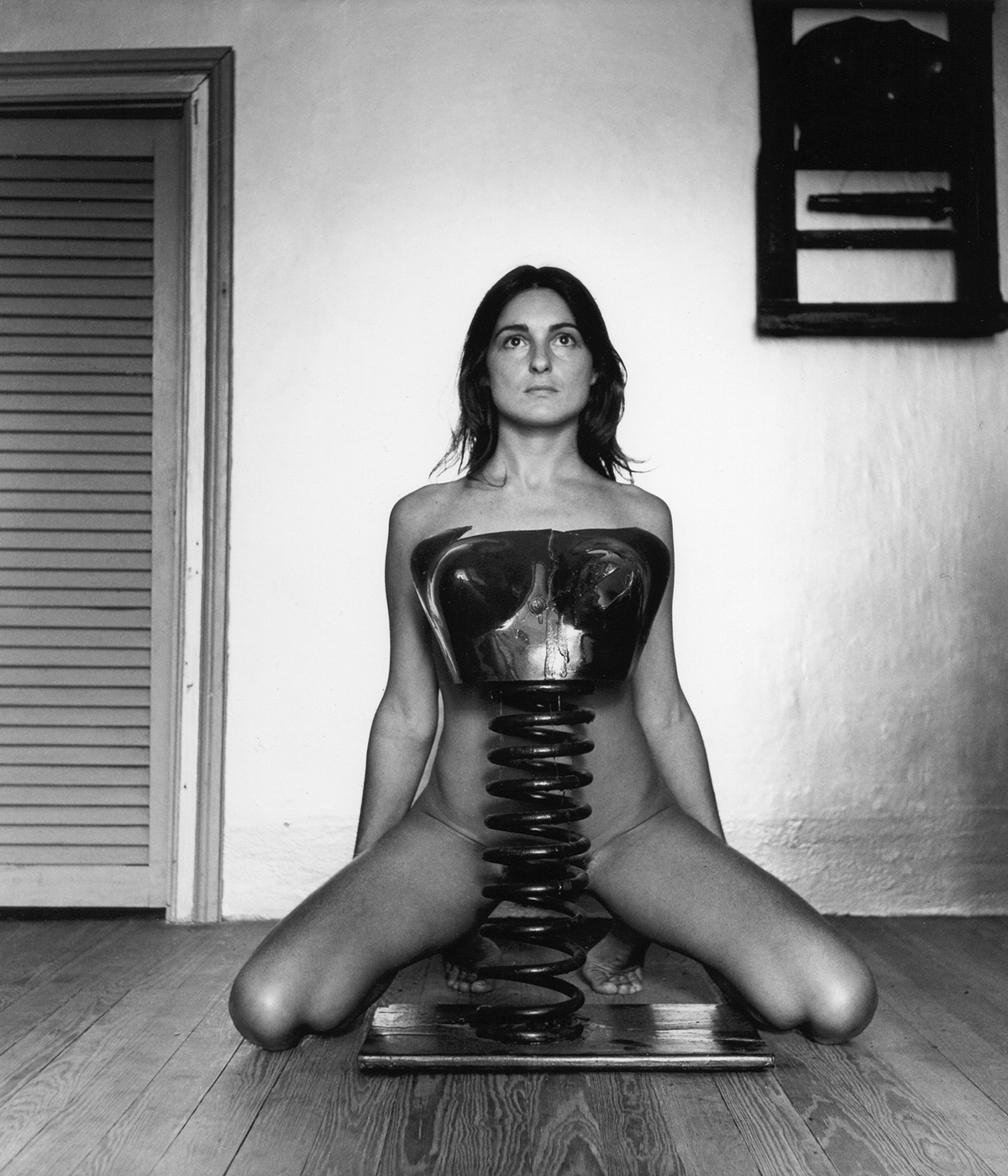

In an evocative series of portraits produced with long-term collaborator Marcos López (Liliana Maresca With Her Work, 1983), Maresca poses nude with a collection of her own sculptures. Made using found objects: pieces of furniture, suspension springs and breast plates - perhaps salvaged from her work in stage design - each sculpture is activated by Maresca’s physical engagement with them. Placed between her legs or held in front of her torso, their aura is ambiguous; appearing either as armour - and Maresca as an emblem of autonomy and resilience - or as torture instruments, with the artist’s naked flesh at their mercy.

By intertwining her identity with her artistic production, Maresca reclaims her body from the state’s censors and simultaneously blurs any distinction between creator and subject, between her art and her politics. 'By including herself in the portraits, Maresca is rejecting the commodification of the artist,' explains Heike Munder, co-curator of this year's Back to the Future section at Artissima. 'A lot of feminist artists protested against this all over Europe and Latin America throughout the 70s and 80s, but the radicality of Maresca’s photographs is a direct consequence of the political context in Argentina.'

SCHULZE ELDOWY GUNDULA Tamerlan, Berlin 1987. Courtesy of the Artist and EBENSPERGER

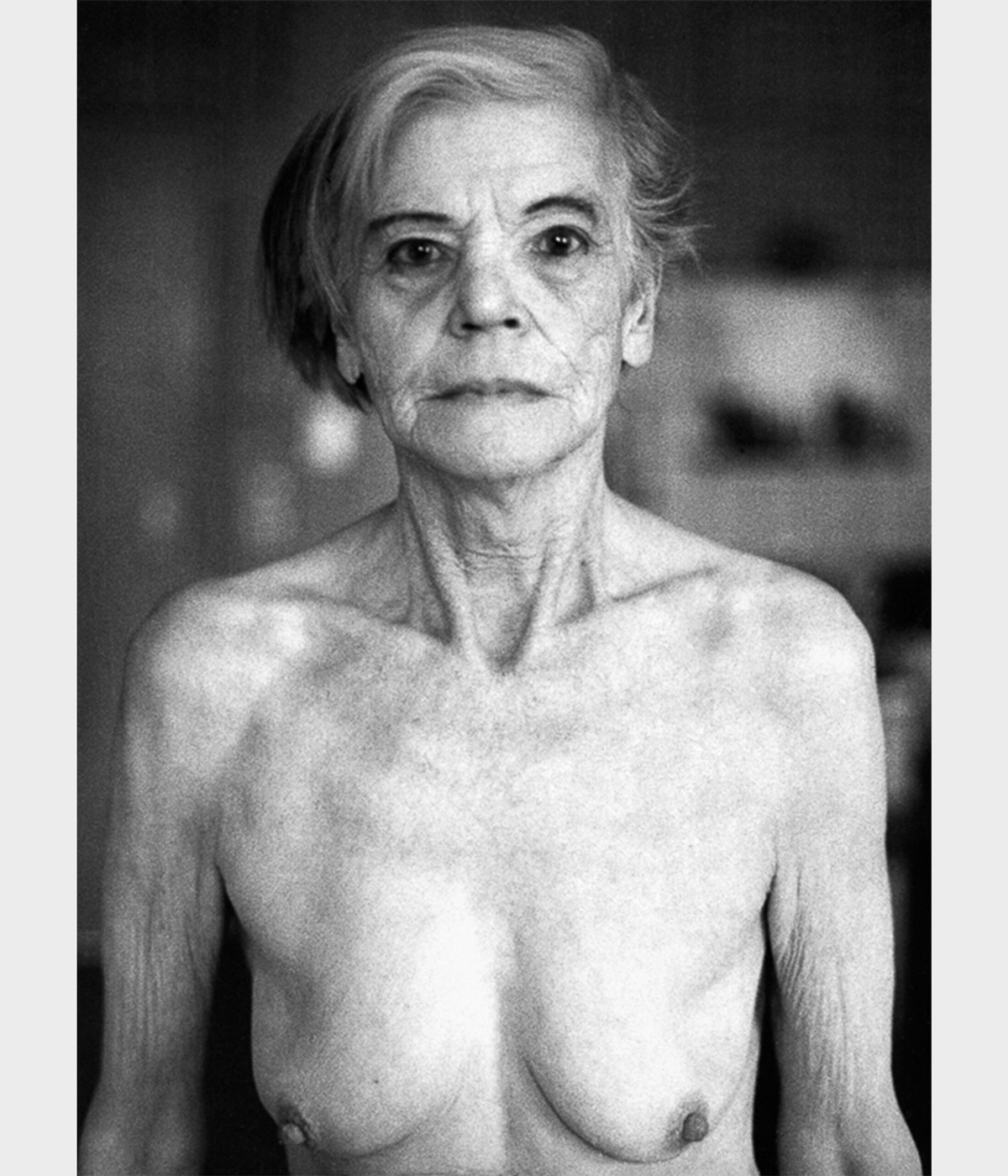

Nudity, either among her subjects or herself, is used to similar effect in the work of Gundula Schulze Eldowy. In her series, Berlin in a Dog's Night (1977-90), started when she was in her twenties and among her best known works, Eldowy explores the unseen lives of ordinary East Berliners amidst the post-war ruins of their city. Countering official GDR narratives of prosperity and social harmony, these portraits of strangers, often taken in their homes, provide intimate and dignified insights into lives of loneliness, illness, poverty and social decay - the marginalised edges of society redacted from official view.

While she perhaps lacks the more confrontational political approach of Maresca, Eldowy’s photographs from this series nonetheless carry a quiet undertone of dissent. Her gritty, monochrome view of individual suffering represents the antithesis to Socialist Realism’s highly polished aesthetic and, in the access she gained to stranger’s homes, provides an assertion of personal space in a state where privacy was routinely violated. Eldowy’s use of nudity is, like Maresca’s, both a statement of radical honesty amidst endless political corruption and a subversion of restrictive state censorship. But in Berlin in a Dog’s Night especially, the nudity of her subjects reflects an almost corporeal connection between East Berliner's and their city. Vulnerable, worn and exposed, stripped back to the foundations, they are presented as an extension of Berlin’s war-torn urban fabric.

SCHULZE ELDOWY GUNDULA Berlin, 1984. Courtesy of the Artist and EBENSPERGER

'The political side to her work only emerged in retrospect, after the wall came down [in 1989],' maintains Patrick Ebensperger, whose eponymous gallery exhibited a series of Eldowy's nude portraits at Gallery Weekend Berlin earlier this year. 'At the time she took the photos it was more about getting in touch with the people. It became more political because nudity was seen as an expression of freedom in the former East Germany - there was always a culture of going to the beach naked, so that was an expression of remaining freedom.'

Wallpaper* Newsletter

Receive our daily digest of inspiration, escapism and design stories from around the world direct to your inbox.

Though Maresca and Eldowy were never acquainted - with Maresca dying of AIDS in 1994 aged 43 - they shared a commitment to channelling resistance and championing the underrepresented in their work. Irrespective of the political obstacles they faced - or perhaps because of them - their photography was honed as a means of protest. In opposition to authoritarianism and censorship, the raw, unfiltered nude body was celebrated by both women as the ultimate expression of individual autonomy.

LILIANA MARESCA Untitled. Liliana Maresca with her artworks 1983. Courtesy Liliana Maresca Estate, Marcos López & Rolf Art, Buenos Aires Photo: Marcos López

-

Extreme Cashmere reimagines retail with its new Amsterdam store: ‘You want to take your shoes off and stay’

Extreme Cashmere reimagines retail with its new Amsterdam store: ‘You want to take your shoes off and stay’Wallpaper* takes a tour of Extreme Cashmere’s new Amsterdam store, a space which reflects the label’s famed hospitality and unconventional approach to knitwear

By Jack Moss

-

Titanium watches are strong, light and enduring: here are some of the best

Titanium watches are strong, light and enduring: here are some of the bestBrands including Bremont, Christopher Ward and Grand Seiko are exploring the possibilities of titanium watches

By Chris Hall

-

Warp Records announces its first event in over a decade at the Barbican

Warp Records announces its first event in over a decade at the Barbican‘A Warp Happening,' landing 14 June, is guaranteed to be an epic day out

By Tianna Williams

-

Artissima 2022: art exhibitions to see this weekend in Turin

Artissima 2022: art exhibitions to see this weekend in TurinTurin art fair Artissima 2022 spans the experimental and the perspective-bending; here’s what to see

By Martha Elliott

-

Rotters' Club: artist Adrián Villar Rojas and his crew hit Turin

Rotters' Club: artist Adrián Villar Rojas and his crew hit TurinBy Emma O'Kelly