Discover Rotimi Fani-Kayode's fluid photographs of the queer male body, on show in London

‘Rotimi-Fani Kayode: The Studio – Staging Desire’ at Autograph ABP celebrates the work of the Nigerian-born photographer

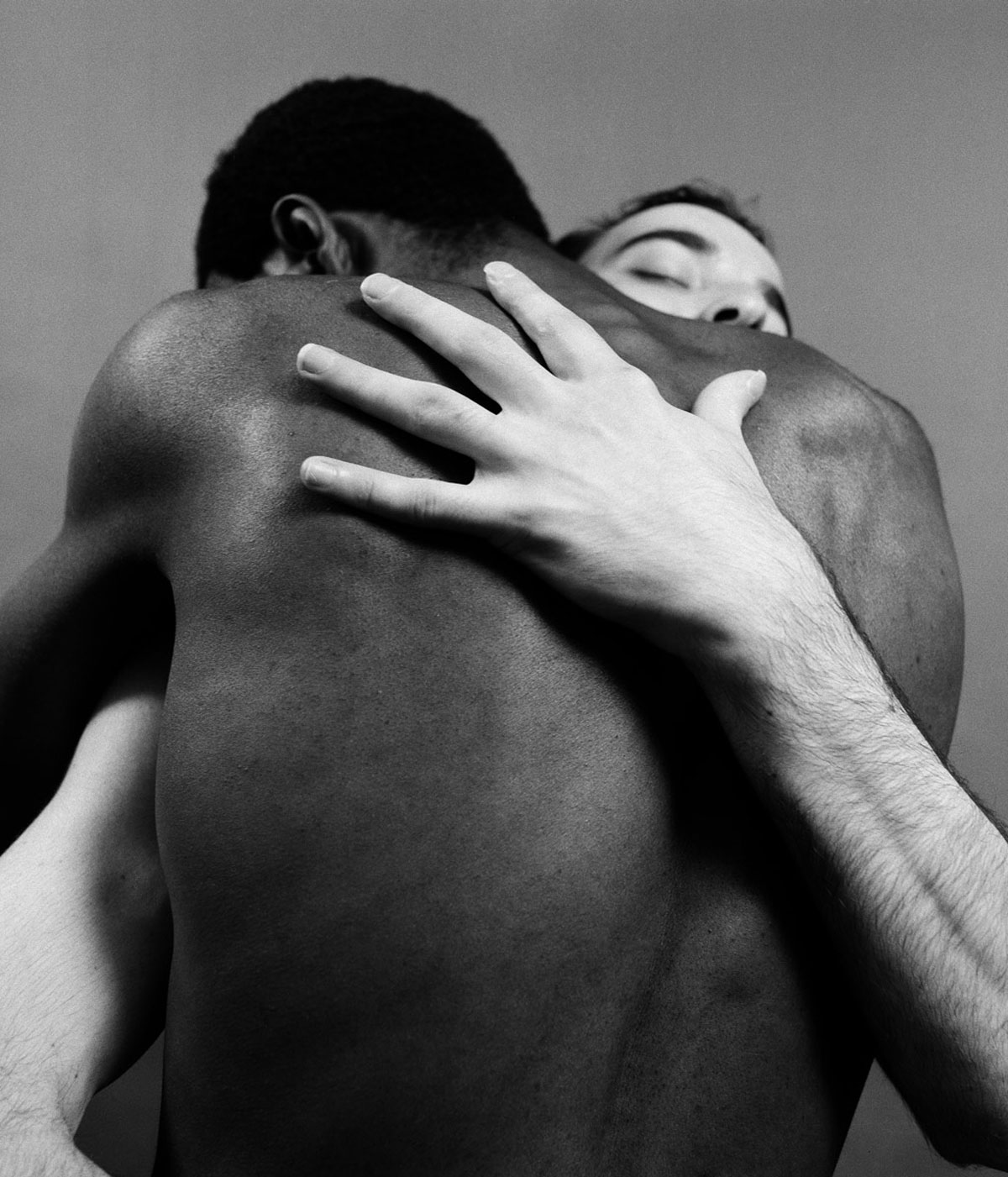

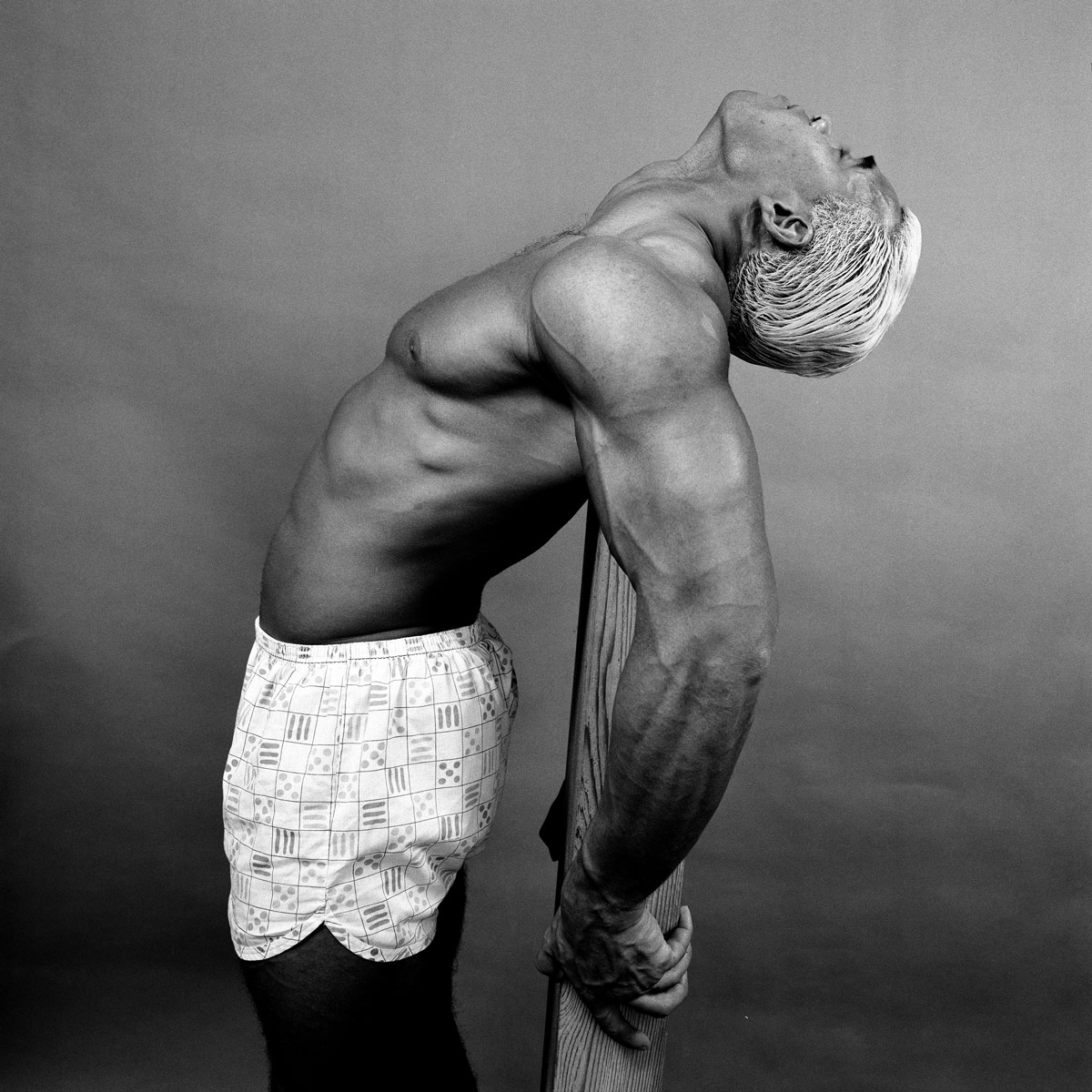

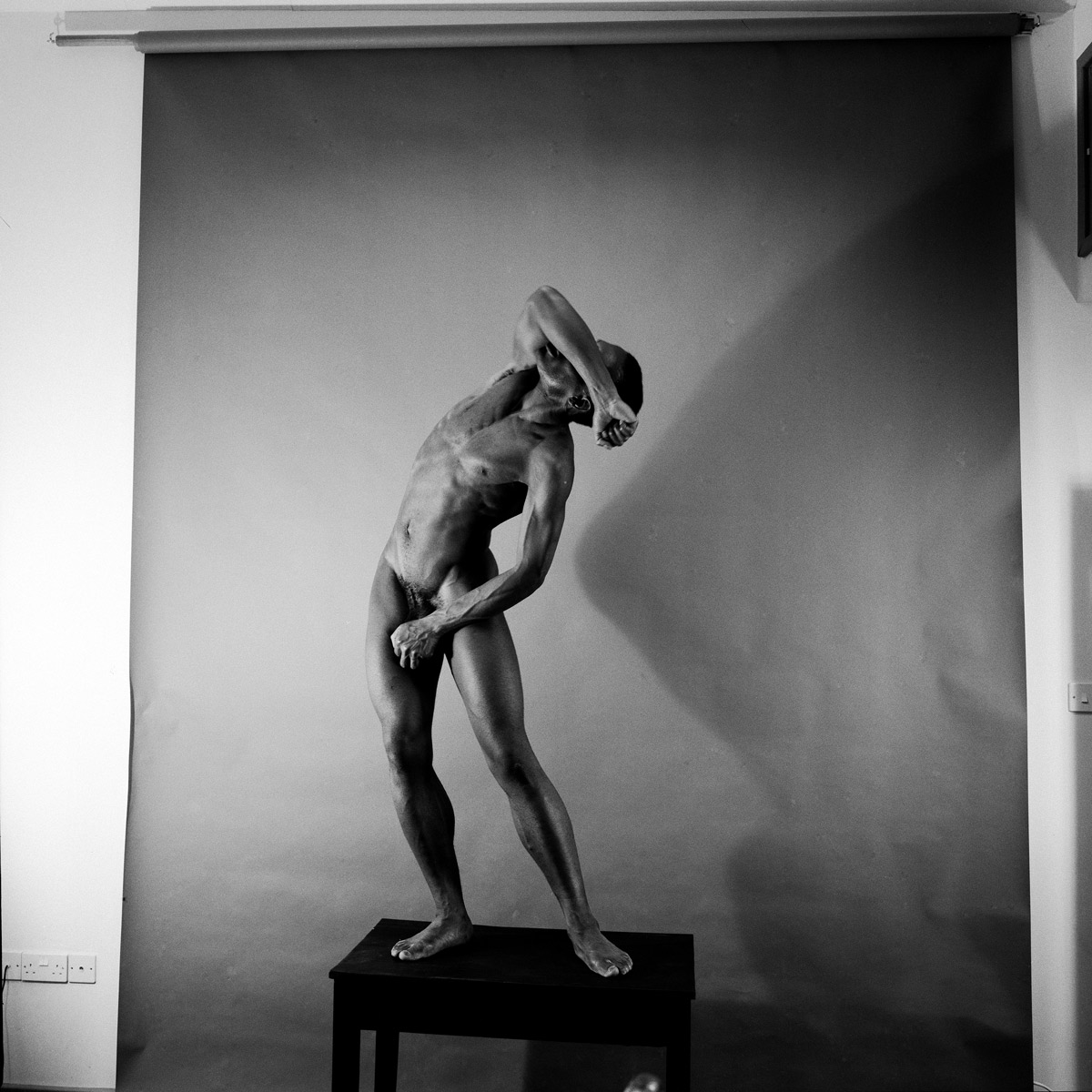

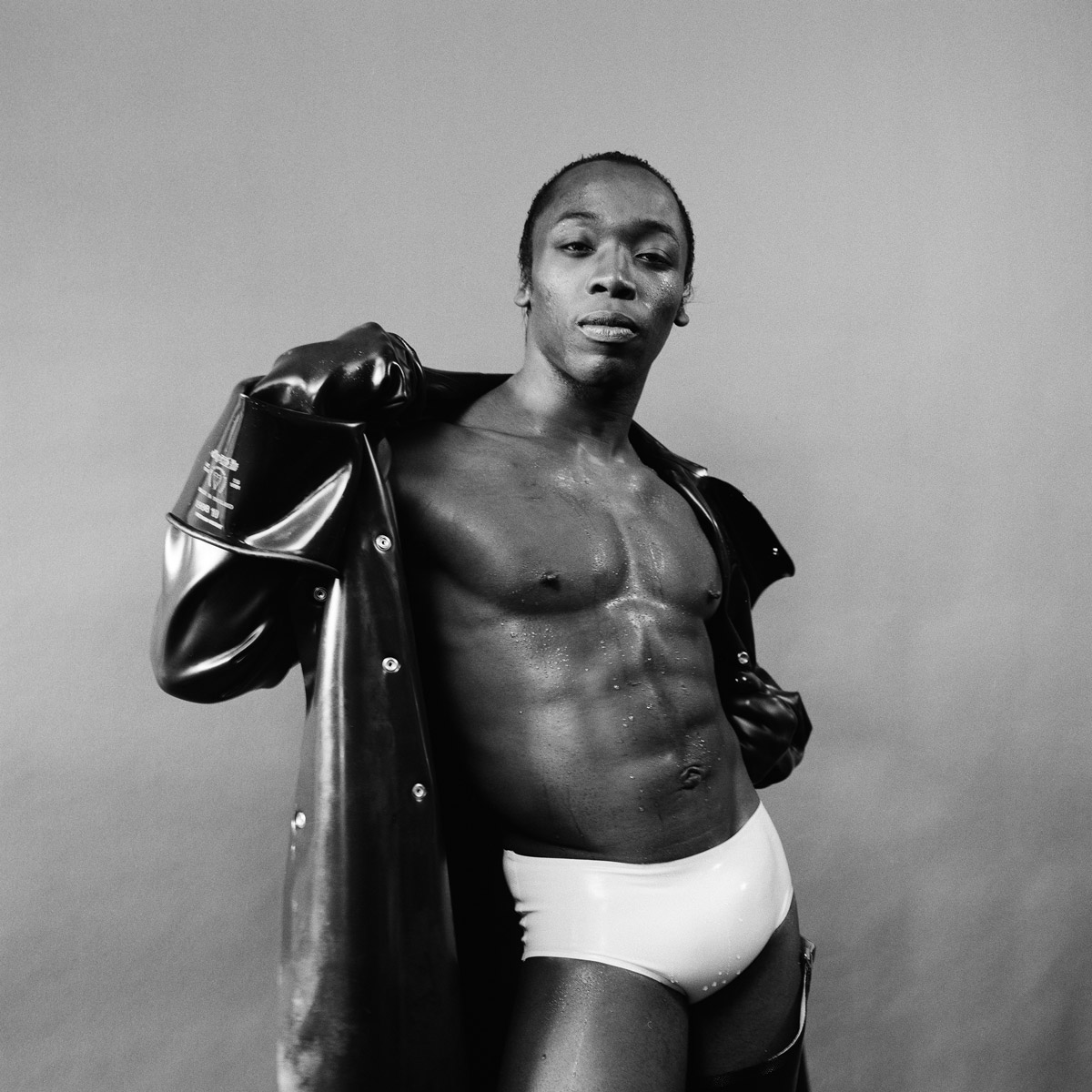

Arching his arms to cover his eyes, a man bends sideways. Standing on a table that transforms his posture to the statuesque, his presentation of his physicality almost reminds one of Michelangelo’s David, although here there is an essence of quiet comfort as he performs his sexuality in the photographer’s dimly lit south London studio. Rotimi Fani-Kayode’s photographic practice during the AIDS years of the 1980s was short but ran electric in its conscious performativity, while depicting the queer male body and its political and spiritual associations. It’s seen here in an exhibition, ‘Rotimi Fani-Kayode: The Studio – Staging Desire’, at Autograph ABP in London (until 22 March 2025).

One of Fani-Kayode’s last listed addresses, before he passed away in 1989, was a ten-minute walk from the Autograph building. Autograph ABP (Association of Black Photographers), the nascent organisation he chaired, was founded with a group of other artists including Sunil Gupta, Armet Francis and Monika Baker, to support Black photographers – as no one else was. Current Autograph director and curator Mark Sealy wrote in a catalogue for the photographer's posthumous, 1995 exhibition, ‘Communion’, that when Fani-Kayode tried to generate interest in his work, curators couldn’t grasp his references. ‘Quite simply, his practice was not understood,’ he wrote. Sealy worked alongside Fani-Kayode, and he tells Wallpaper* that, ‘in the 1980s, post-Second World War migrant kids were coming out of university, wanting to make creative spaces. They were simply asking the question, “We pay our taxes – why can’t we have access to spaces and funding to support our work?”’

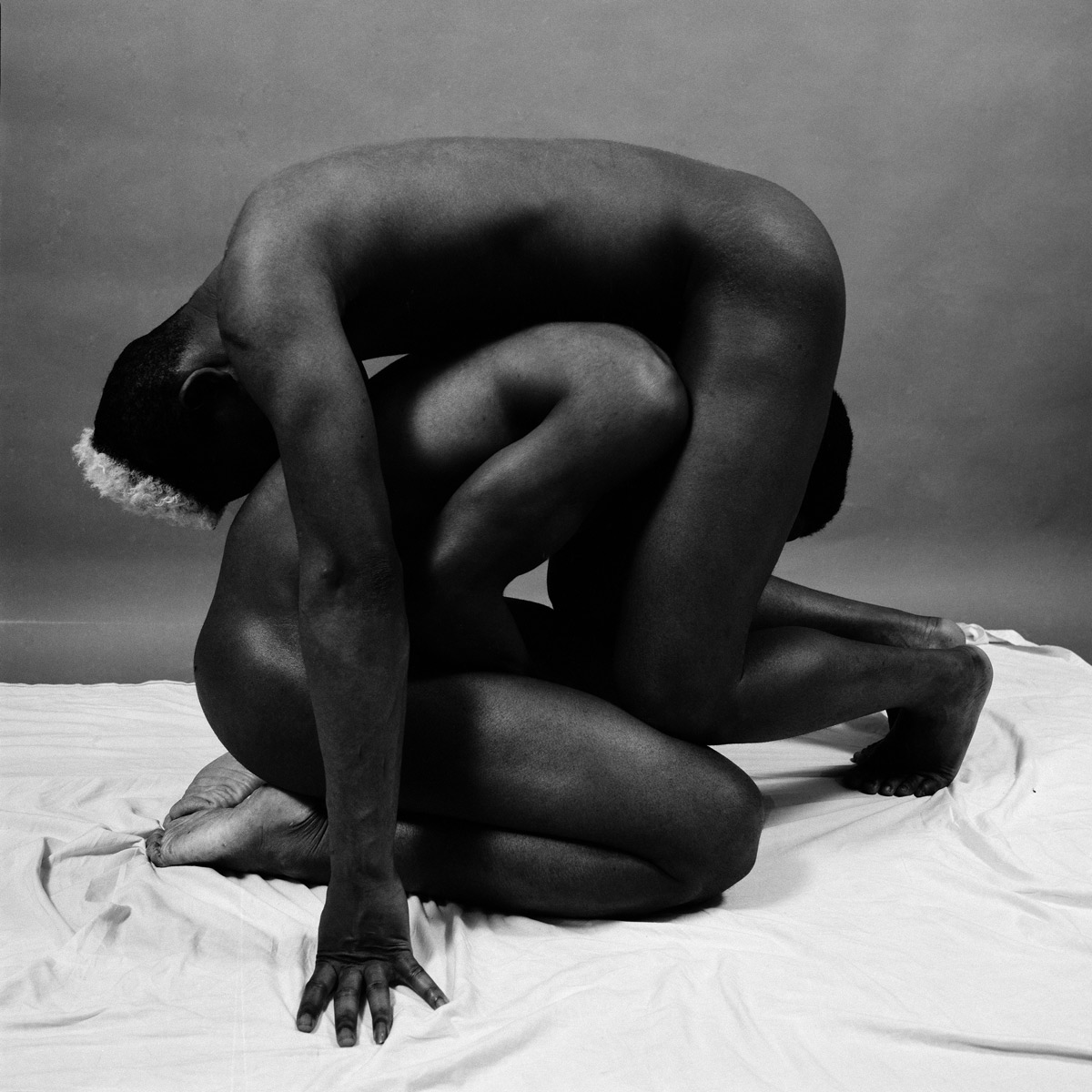

A ten-year-old Fani-Kayode had to leave his home in Nigeria with his parents – his father being the Balogun chief of Ife, the year before the Biafran secession (the state declared independence in 1967 and a civil war followed), and move to Brighton, UK. Looking at one of the exhibited works at Autograph – a nude man playing the Yoruban thumb piano, the agidigbo, eyes closed, and face drawn in peaceful ecstasy, almost transcending towards the sexual – it is evident that the photographer was extremely aware of his Yoruban identity in his practice.

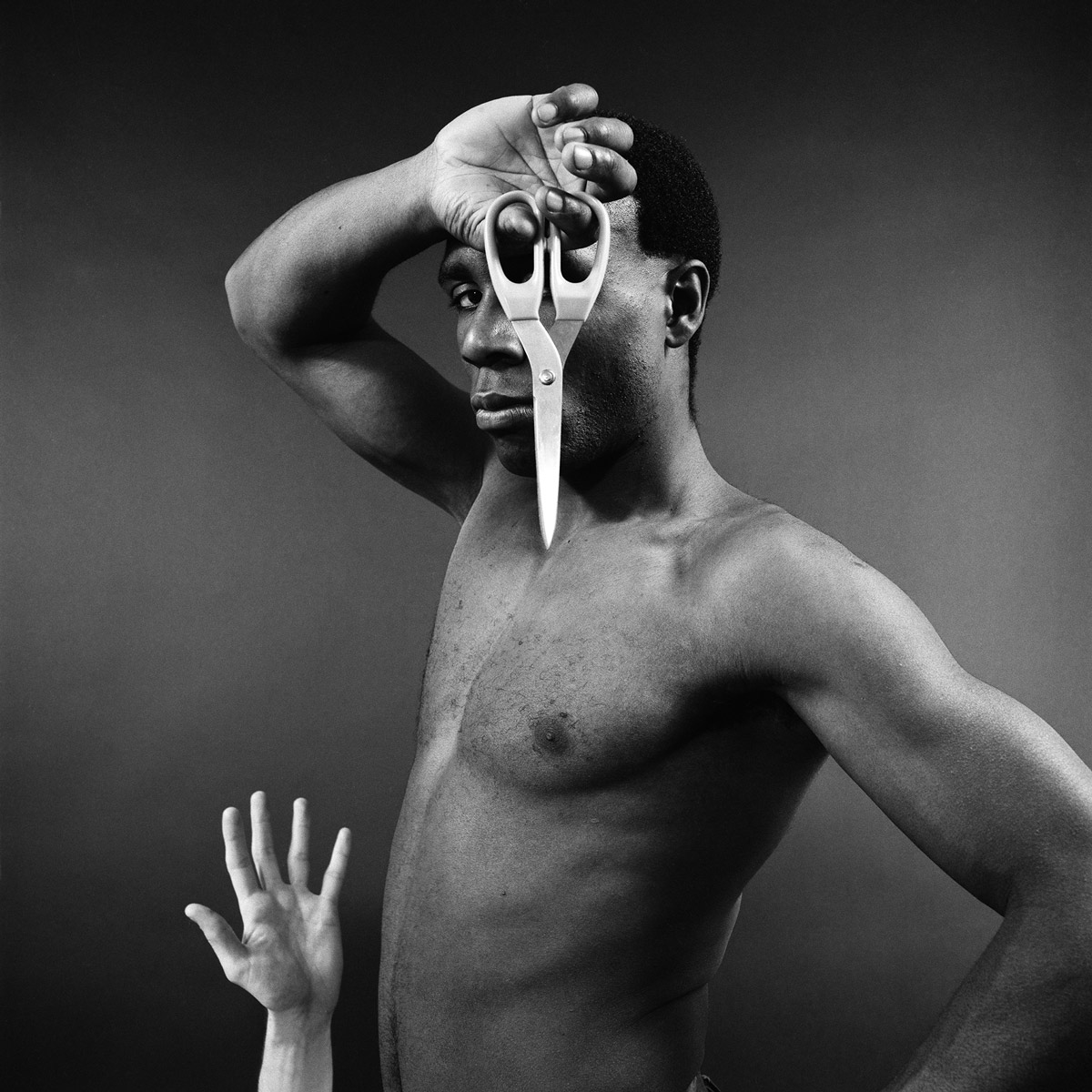

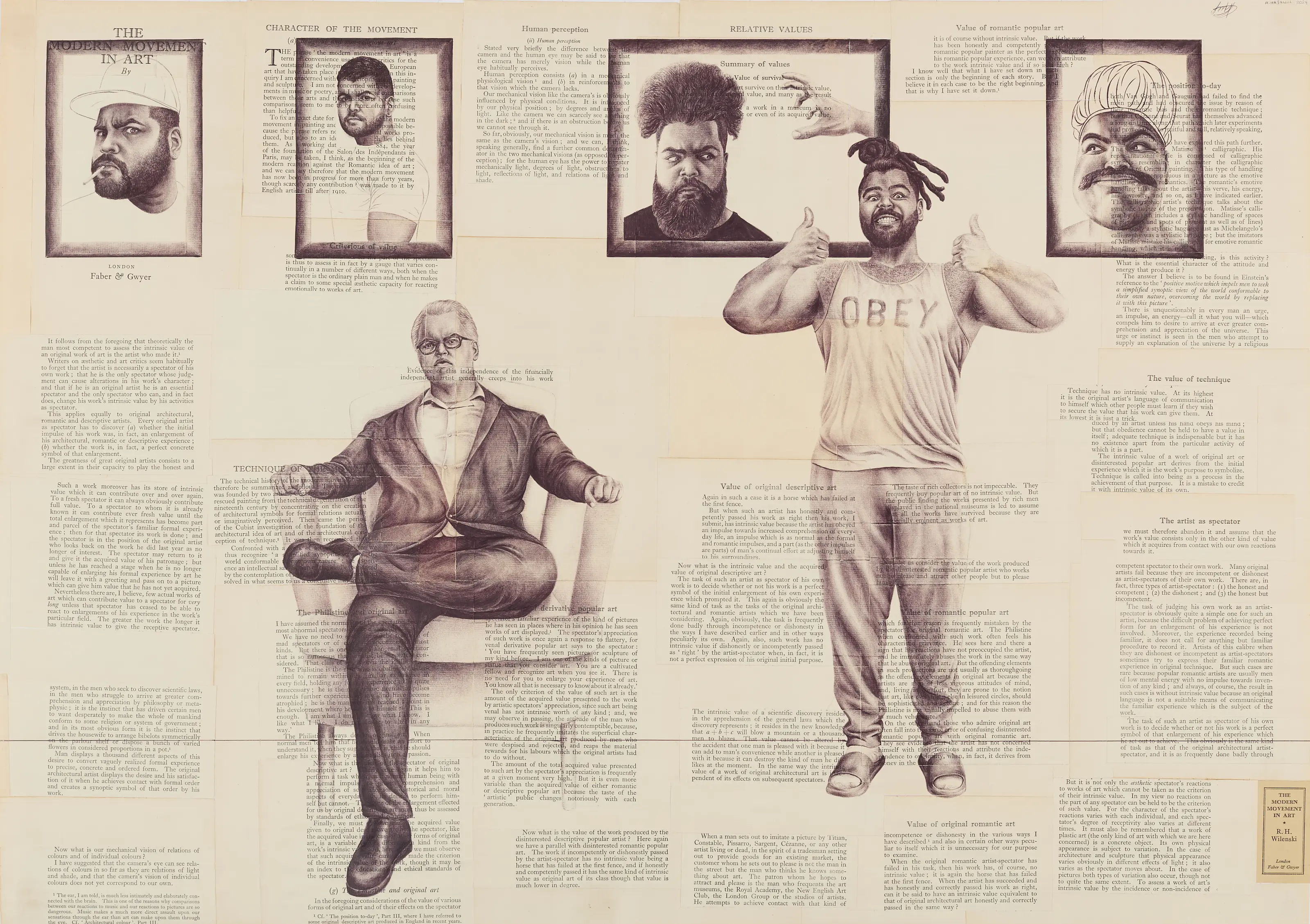

It immediately finds a reference in the stereotype of musical prodigy in Africa, seen across literature and painting – like in William Hogarth’s ‘Captain Lord George William Graham in his Cabin’ (1745) of a young Black boy playing the pipe and tabor, or in the sexualisation of Black figures in Western art, such as in John Philip Simpson’s bare-chested slave in The Captive Slave’(1827). ‘He’s trying to break down the long arc of historical representations of phallocentric work that objectifies the Black male body,’ according to Sealy. ‘He’s in dialogue with the classical European art tradition and he creates conversations culturally – you have Greek antiquity fused with Yoruba spiritualism, fused once more with ideas of homoerotic desire.’

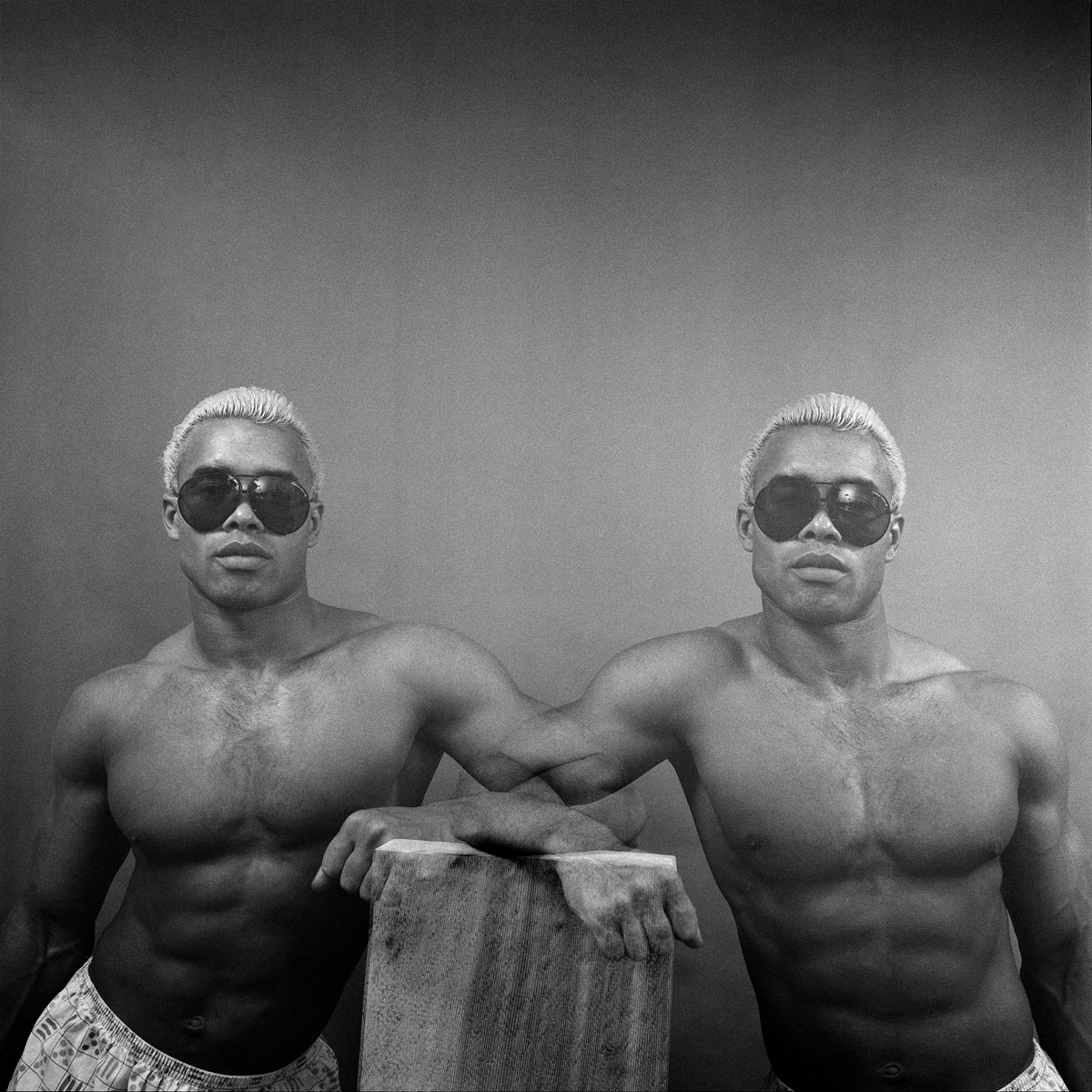

In another photograph, two men in bleached and gelled hair seem to lean on a pillar, sunglasses on and chests glistening under the light. Fani-Kayode would have probably encountered similar figures during his college days in Washington – where the majority were Black. W Ian Bourland writes in Bloodflowers: Rotimi Fani-Kayode, Photography, and the 1980s how the late-night parties, dancing, drugs, hustlers and sex in public propelled Fani-Kayode’s transition from ‘the “respectable sort” that his family wanted him to be, to another world hidden in plain sight’.

Heterosexism was taken as ‘part and parcel of Black identity’ in Black radicalism and the Black Arts Movement. Sunil Gupta recalled that the one thing he and Fani-Kayode had in common was that they were both very gay, and quite out about it. ‘We managed to turn Autograph towards a queer direction, which it might not have had otherwise,’ he said. ‘One of the key exhibitions at the time was “The Other Story” at the Hayward Gallery [1989-90] by Rasheed Araeen and it was not interested in queerness at all.’ Thus, Fani-Kayode’s queerness also meant a certain kind of alienation – both from Nigeria with its homophobia, and from the art world in the UK, where his work was not seen as being in ‘good taste’ and ‘gallery-appropriate’, Sealy's catalogue noted.

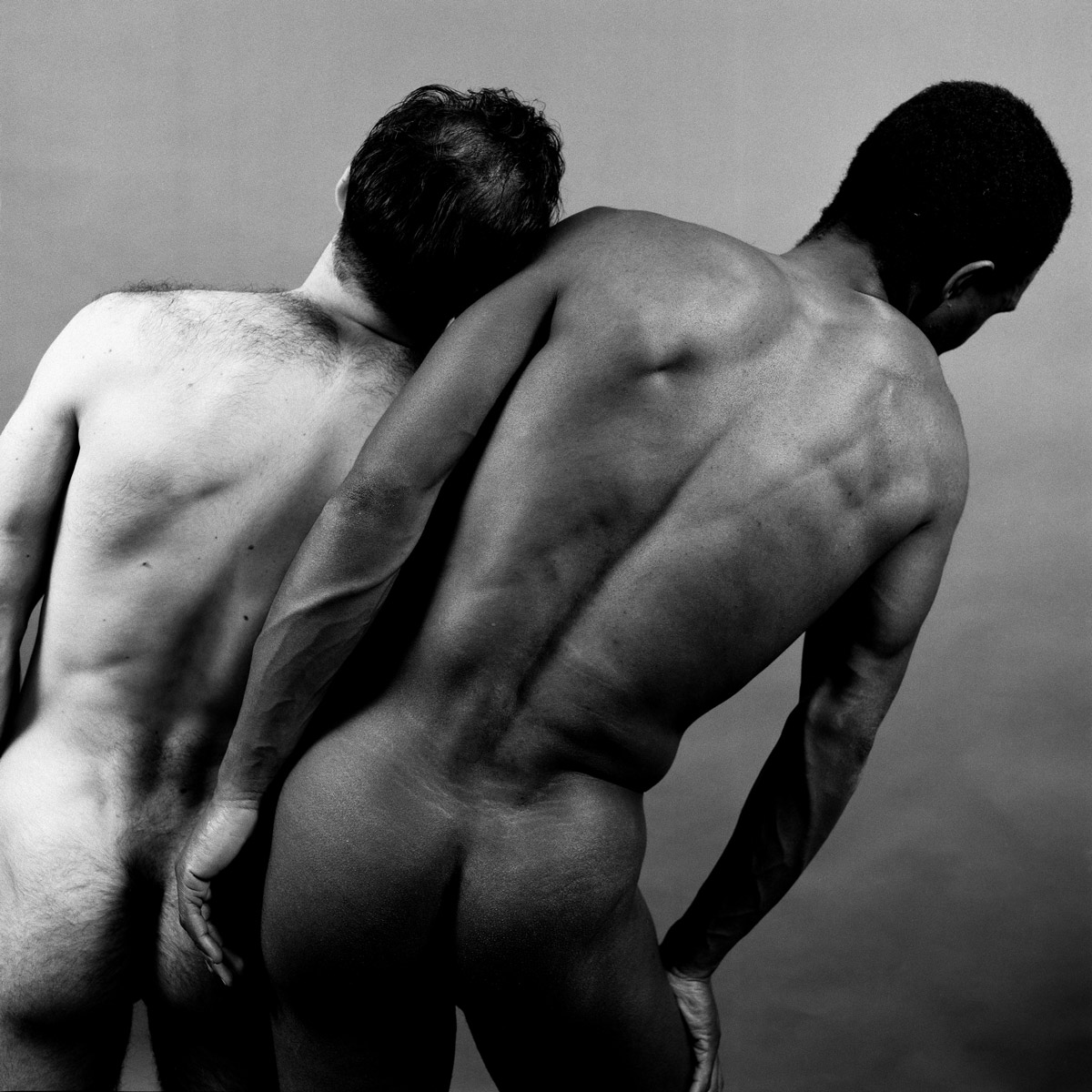

‘His work is not about resolving these discrepancies,’ Sealy tells Wallpaper*. ‘It’s much more hybrid than these traditions. It comes from an unresolved scholarly place of investigation.’ The approach extended to his relationships; Gupta recalled that it became cool to have a partner of another race. ‘We identified that part of the problem about race is that people don’t know about other races,’ he said. ‘Both of us had white British partners. We hung out together, had very mixed-race parties and went out to nightclubs.’

Receive our daily digest of inspiration, escapism and design stories from around the world direct to your inbox.

Trying to renegotiate these boundaries, Fani-Kayode consistently took from Yoruba cosmology in his works. On a closer look, the two men in sunglasses are one and the same, photographed as twins – their hands intertwined in phantom superimposition, using multiple exposure, which the photographer frequently resorted to. He also frequently depicted twins and quadruplets, in works such as Four Twins, taking from the significance of twin births in Yoruban mythology, where they are thought to be connected to the spiritual realm, and also denote power instability and mischief – which becomes significant considering the two queer club-goers.

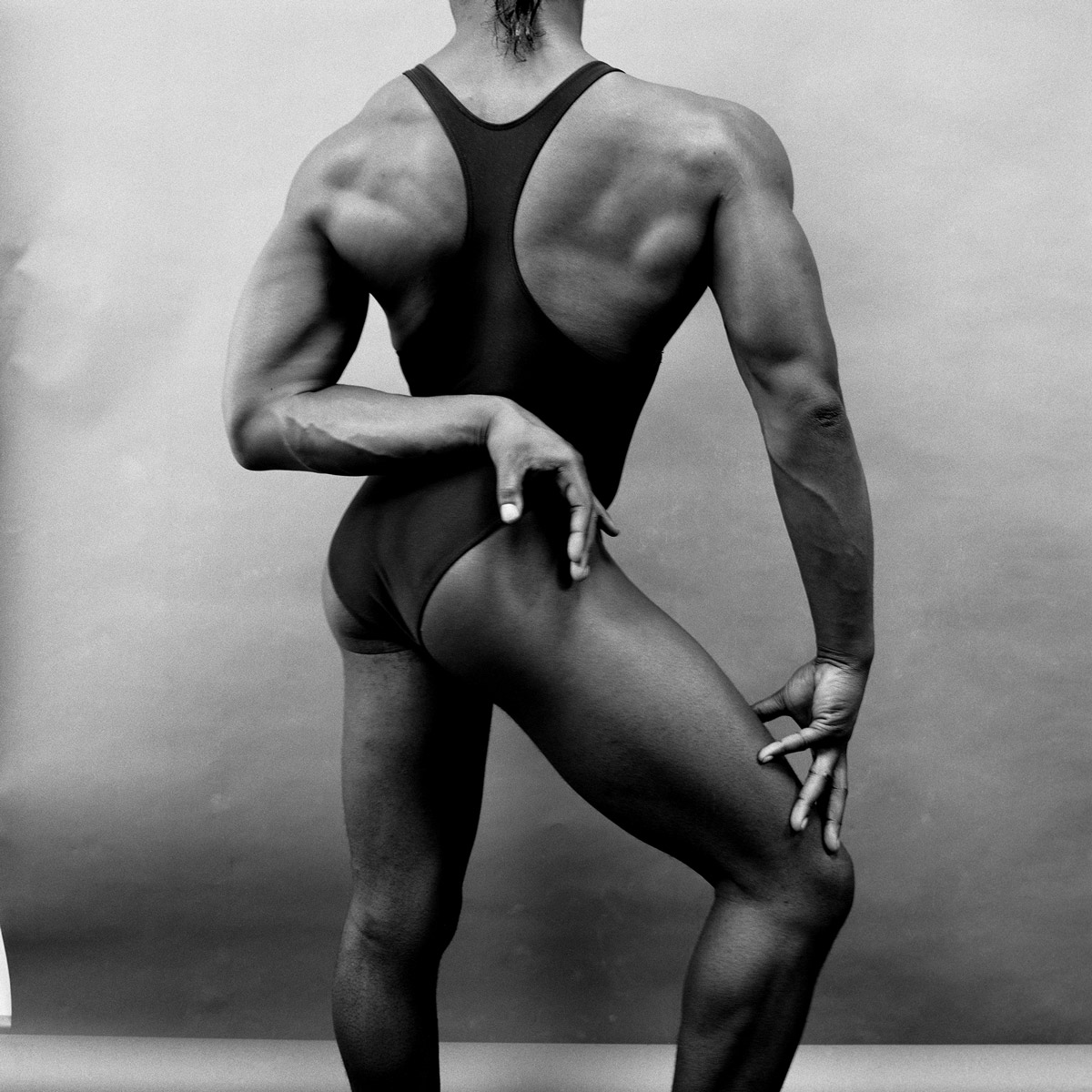

Having met Robert Mapplethorpe in New York, fetish and leather culture was a significant part of Fani-Kayode’s work. In the late 1970s, one would primarily find the male photographic nudes, particularly the beefcake archetype, in muscle and fetish magazines, noted Bourland – the visual language of which Fani-Kayode does follow. It is through gay newsletters and journals, particularly Square Peg and interestingly a softcover book by Gay Male Press, that he started publishing his work. ‘That’s where he disrupts the narrative,’ observes Sealy, ‘getting that stuff published and put into the public realm.’

Along with taking up commercial jobs besides his own practice, Fani-Kayode was a tutor at the Oval House Theatre (now Brixton House) in 1985 and 1986 – he photographed a man called Errol there, wrapping his arm around a stick in a show of physical strength and eroticism. While there was a phase during which Fani-Kayode photographed in the streets, he moved on to the studio and its theatricality. ‘He’s very interested in that world,’ says Sealy. ‘He’s photographing dancers – theatre, spectacle and props – they’re all in the work. The later colour work is very theatrical, staged, but at the same time it’s replicating and working through Caravaggio, Rembrandt. Taking a small one-bedroom flat in Brixton and turning it into a three-hundred-year conversation with art history is quite radical.’

When Autograph was established, photography was not considered a serious art practice. Sealy recalls that one of the first places Fani-Kayode’s work was recognised was in France. ‘You’re dealing with places where there are very few Black African curators who would get the work, very few white curators who would think the work is relevant,’ he says. ‘Most people have what I would call a reductive eye, unless they have a sense of purchase in the work.’ It was the community around him – like the photographer Ajamu X, who lived in the same community building that Fani-Kayode and a group of activists and artists sharing the same politics were squatting in, or Dennis Carney, the gay rights activist – who were collaborators in helping him build a vision, as they modelled for him. ‘This was done out of support,’ says Sealy. ‘It’s an endearing transaction’

‘Rotimi Fani Kayode: The Studio – Staging Desire’ is at Autograph ABP, London, until 22 March 2025

Upasana Das is a freelance writer working on fashion, art and culture. She has written for NYT, Dazed, Interview Mag, Vogue India and Harper's among others.

-

Doc’n Roll Festival returns with a new season of underground music films

Doc’n Roll Festival returns with a new season of underground music filmsNow in its twelfth year, the grassroots festival continues to platform subcultural stories and independent filmmakers outside the mainstream

-

Commune Design’s new rug collection is a psychedelic trip

Commune Design’s new rug collection is a psychedelic tripThe Los Angeles-based company worked with Christopher Farr on its groovy rug collection inspired by 1960s and 1970s Northern California

-

The Hart Marylebone marks the next chapter in London’s design-led pubs

The Hart Marylebone marks the next chapter in London’s design-led pubsThe trio behind The Pelican and The Hero turn to Marylebone, fusing Victoriana, intimacy and culinary honesty in their most ambitious project yet

-

Doc’n Roll Festival returns with a new season of underground music films

Doc’n Roll Festival returns with a new season of underground music filmsNow in its twelfth year, the grassroots festival continues to platform subcultural stories and independent filmmakers outside the mainstream

-

Out of office: The Wallpaper* editors' picks of the week

Out of office: The Wallpaper* editors' picks of the weekThe London office of Wallpaper* had a very important visitor this week. Elsewhere, the team traverse a week at Frieze

-

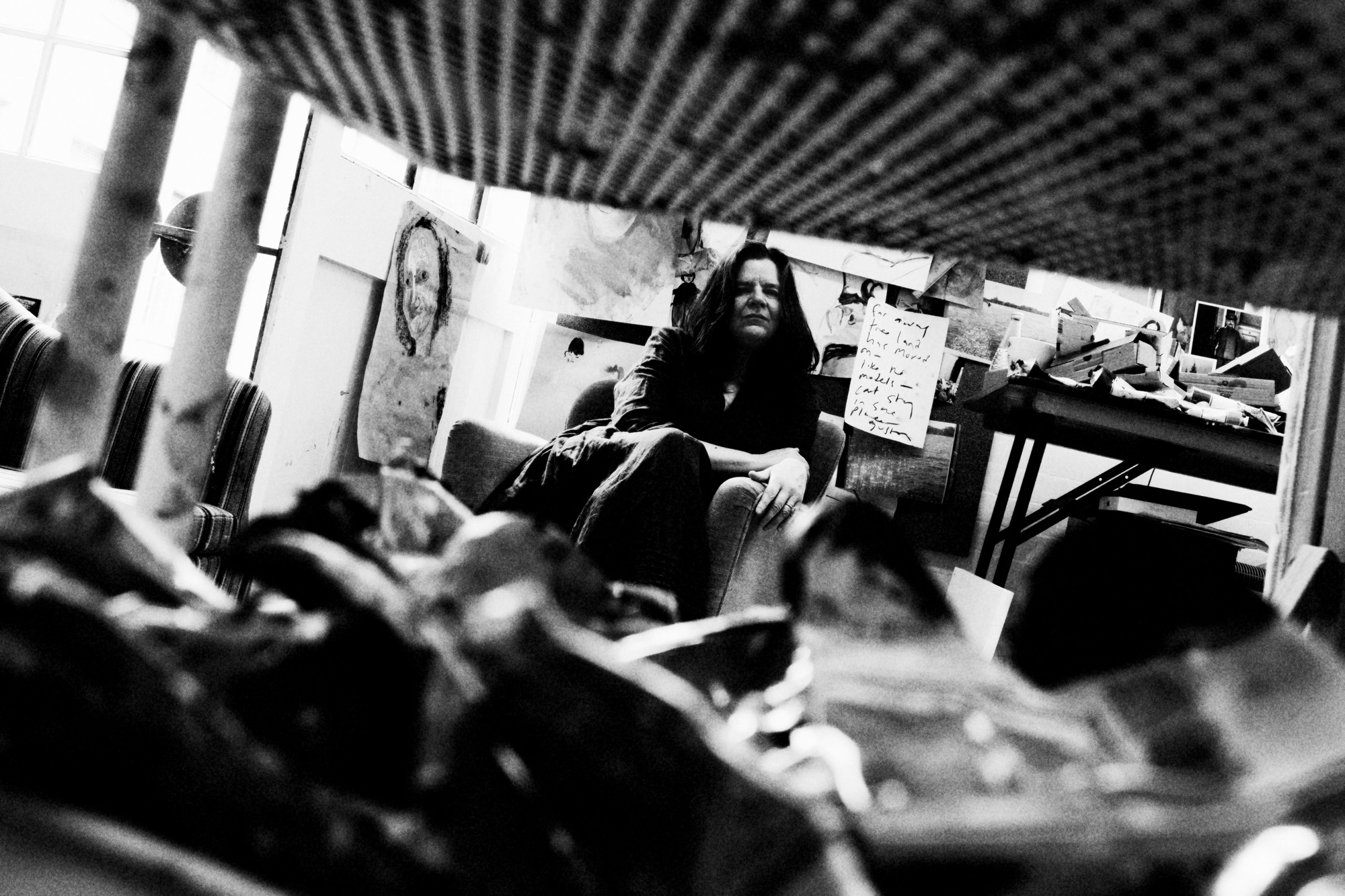

Chantal Joffe paints the truth of memory and motherhood in a new London show

Chantal Joffe paints the truth of memory and motherhood in a new London showA profound chronicler of the intimacies of the female experience, Chantal Joffe explores the elemental truth of family dynamics for a new exhibition at Victoria Miro

-

Leo Costelloe turns the kitchen into a site of fantasy and unease

Leo Costelloe turns the kitchen into a site of fantasy and uneaseFor Frieze week, Costelloe transforms everyday domesticity into something intimate, surreal and faintly haunted at The Shop at Sadie Coles

-

Can surrealism be erotic? Yes if women can reclaim their power, says a London exhibition

Can surrealism be erotic? Yes if women can reclaim their power, says a London exhibition‘Unveiled Desires: Fetish & The Erotic in Surrealism, 1924–Today’ at London’s Richard Saltoun gallery examines the role of desire in the avant-garde movement

-

Tiffany & Co’s artist mentorship at Frieze London puts creative exchange centre stage

Tiffany & Co’s artist mentorship at Frieze London puts creative exchange centre stageAt Frieze London 2025, Tiffany & Co partners with the fair’s Artist-to-Artist initiative, expanding its reach and reaffirming the value of mentorship within the global art community

-

Em-Dash is a small press redefining the indie zine beyond nostalgia

Em-Dash is a small press redefining the indie zine beyond nostalgiaThe South London publishing studio's new imprint 'Practice Meets Paper' translates a chosen artist’s practice into print. Wallpaper*s senior designer Gabriel Annouka speaks with the founders, Saundra Liemantoro and Aarushi Matiyani, to find out more

-

‘It is about ensuring Africa is no longer on the periphery’: 1-54 Contemporary African Art Fair in London

‘It is about ensuring Africa is no longer on the periphery’: 1-54 Contemporary African Art Fair in LondonThe 13th edition of 1-54 London will be held at London’s Somerset House from 16-19 October; we meet founder Touria El Glaoui to chart the fair's rising influence