Playtime: Isaac Julien's new London shows delve into the financial world's underbelly

Art doesn't talk much about money. Which is ironic really. It certainly doesn't talk about art's new status as asset class. Isaac Julien's new film installation 'Playtime', which opens today at the Victoria Miro gallery Islington branch, talks about money and art and the damage done across seven large screens for over 70 minutes. In one segment the actor/artist/poet James Franco, a slick black-suit-white-shirt black-tie avatar of the contemporary art market (filmed in the room where he is now projected), sells art as 'treasure' to be hoarded, shared and enjoyed. It is mesmerising (and Franco's case almost convincing).

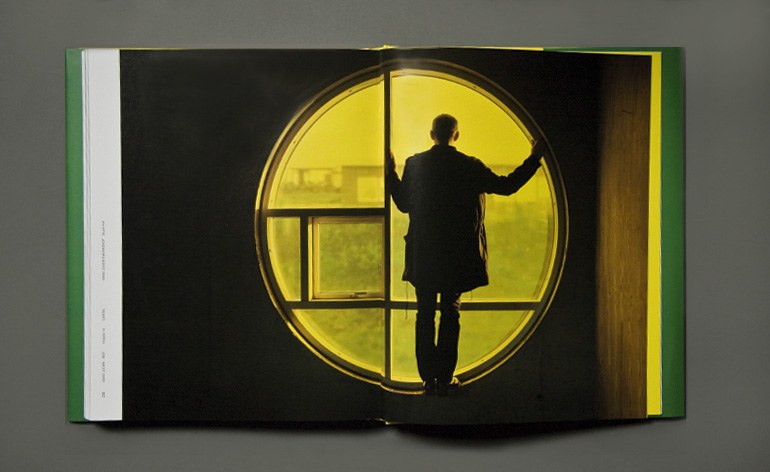

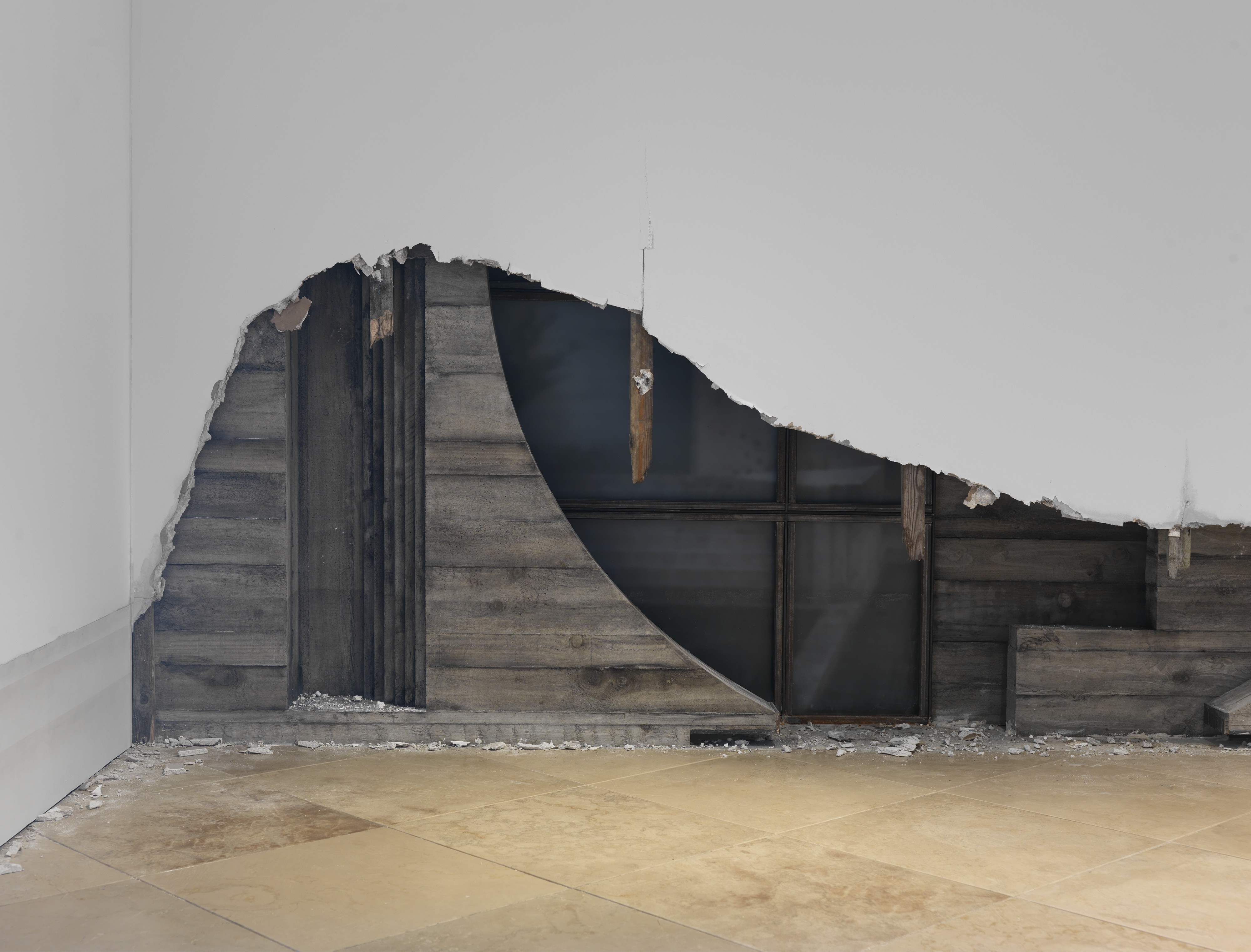

Contemporary art isn't much for narrative, lyricism or beauty either. Playtime has it all. Another segment, based on interviews with the photographer Thorsten Henn, Julien's friend and occasional collaborator, tells the story of an Icelandic creative who gets part way to building his modernist dream home only to have the bank withdraw its funds as the country falls into a financial black hole of its own creation. The crushed creative haunts his modern ruin and rages against a system that failed to warn him that credit is a cruel mistress while outside the harsh landscape of rock and snow remains beautifully indifferent. At one point the Henn stand-in is framed, burned alive in his feature round window that has become a dying sun.

In another segment the Chinese actress Maggie Cheung conducts an (entirely scripted) interview with the auctioneer Simon de Pury. He looks a bit like the big bad wolf, licking his chops at the idea of the hammer coming down on a big digit sale. A two-screen video installation, 'Kapital', in which the artist talks turkey with academics such as Stuart Hall and David Harvey, has been installed in the lower gallery.

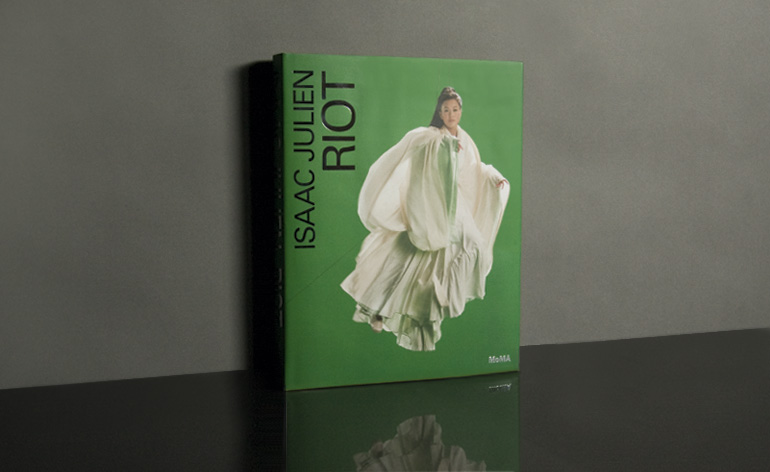

Playtime was three years in the making and is the most ambitious project yet for an artist who has done a reverse Steve McQueen, making his first movie, Young Soul Rebels in 1991, before moving into photography and video art. Now 53, Julien is currently available in multiple formats. Victoria Miro is running an exhibition of accompanying Playtime photography at its new Mayfair gallery while his nine-screen video installation, Ten Thousand Waves, is at MOMA in New York until February 17. MOMA has also just published Riot, a career retrospective.

We caught up with artist Isaac Julien as technicians corrected colour balance in preparation for Playtime’s opening...

W*: There is not much art about money. And there is certainly not much art about art as asset class. It’s a dirty secret in a way. You are talking about it very explicitly.

Isaac Julien: Different artists address it in different ways. I think that Jeff Koons does, and it is not a dirty secret in his work. It is very implicit in Damien Hirst’s work. I was really interested in having a discussion. Hence making and showing Kapital as well. And it is not just about art, or the art world, everyone is part of this conversation.

How much of the film is scripted and how much documentary? The interview with Simon de Pury for instance.

All the cases in the film are derived from interviews. Then we edit the interviews, create a script and get the actor to improvise around the script. That’s how the fictional element gets developed and in all the cases we did exactly the same thing. Even with Simon de Pury, we interviewed him over a period of three months. Did an interview, edited that, did a second interview, edited that, and presented him with his text. I’ll let you into a secret though. Maggie Cheung and Simon de Pury never met. That’s why it had to be so scripted. There was about three weeks difference between Maggie asking the questions and Simon answering them. There is a little clue in there, a tracking shot and Simon’s not actually talking to anyone.

The Reykjavik section is a real cautionary tale...

The character is based on the photographer Thorsten Henn. I met him in Iceland in 2004 and he collaborated on a lot of my photographs. And the house in the film is his actual house. He was doing a lot of advertising work and decided to build his dream house. But Iceland was one of the first places that got hit in the crash of 2008. He lost his house, his family, his wife. His story though encapsulates the journey that a lot of people made. And he says: ‘Why did no one stop him?'. But there was this very laissez faire attitude in Iceland. They just left everything completely crash.

Maybe Wallpaper* shares some of the blame. Maybe it’s all our fault for selling this dream of the beautiful modernist home?

Yeah, I was thinking about that house and Wallpaper*. I love Wallpaper*. I don’t think it is your fault. But I see the house as a modern ruin. And what happens to design when there is this trauma, the foreclosure on this modernist dream. It was something really important to have that as a metaphor. The other building he walks through is the Olafur Eliasson-designed concert hall in Reykjavik. And that’s a building that the government decided to go ahead with, despite the crash. Both projects are about ambitions and desires in design and architecture. It’s a beautiful house you know but two months after we filmed there some kids set it on fire. Thorsten still sort of owns that house and he would like for it to be turned into an art space in some way. It was built to be an artist’s studio and I think it would be fantastic if there was an art organisation or patron who could look at space and reconfigure it, do some conservation work on it and for it to be what it was originally intended to be.

More generally, you are not afraid to be beautiful and use narrative, which is not what everybody wants to be doing at the moment in contemporary art.

That lyricism relates to the cinema of people like Derek Jarman, the kind of cinema that I liked to see. That could be part of a British culture, instead we are given a certain stereotype of what images should go with certain subjects.

With the success of Steve McQueen, are you suddenly getting hollywood execs calling looking for another black British artist and filmmaker?

No. I think what is interesting though is that you have Steve’s success with nine-Oscar nominations and you have John Akomfrah’s piece about Stuart Hall, which is on at Tate Britain at the moment. I do think that needs to be acknowledged somehow - there are these black artists who have been working in film, working in our own different ways.

And maybe it will be more accepted to bounce from art to film and back again? But you did it the other way round, made the movie Young Soul Rebels and then moved into art.

Yeah, well the reason I did it was I didn’t want to get bored. There was something a bit boring about British Cinema. I don’t want to knock it too much, we have done very well, but I don’t think that the real excitement and creativity of Britain is really allowed to shine at the moment. If they look around the visual field, they would find lots of different voices.

Comprising three 'chapters', Playtime, is set across three cities defined by their relationship to money: London, a city transformed by the deregulation of banks; Reykjavik, where the crisis began in 2008; and Dubai (pictured), one of the Middle East's thriving financial markets. Courtesy the artist and Victoria Miro, London © Isaac Julien.

Watch a preview of Isaac Julien's new video work 'Playtime', 2014, unfold. © Isaac Julien. Courtesy the artist, Victoria Miro, London and Metro Pictures, New York

In one segment the actor/artist/poet James Franco, a slick black-suit-white-shirt-black-tie avatar of the contemporary art market (filmed in the room where he is now projected), sells art as 'treasure' to be hoarded, shared and enjoyed. Courtesy the artist and Victoria Miro, London © Isaac Julien.

In another segment the Chinese actress Maggie Cheung conducts an entirely scripted interview with the auctioneer Simon de Pury. Courtesy the artist and Victoria Miro, London © Isaac Julien.

A two-screen video installation, 'Kapital', in which the artists talk turkey with academics such as Stuart Hall and David Harvey, has been installed in the lower gallery. Courtesy the artist and Victoria Miro, London © Isaac Julien.

Meanwhile, Victoria Miro is running an exhibition of accompanying Playtime photography at its new Mayfair gallery. Pictured is 'EMERALD CITY / CAPITAL (Playtime)', 2013. Courtesy the artist, Victoria Miro, London and Metro Pictures, New York © Isaac Julien

'HORIZON / ELSEWHERE (Playtime)', 2013. Courtesy the artist, Victoria Miro, London and Metro Pictures, New York © Isaac Julien

'MIRAGE (Playtime)', 2013. Courtesy the artist, Victoria Miro, London and Metro Pictures, New York © Isaac Julien

Playtime's Reykjavik chapter, based on interviews with the photographer Thorsten Henn, tells the story of an Icelandic creative who gets part way to building his modernist dream home only to have the bank withdraw its funds as the country falls into a financial black hole. Pictured is 'ALL THAT'S SOLID MELTS INTO AIR (Playtime)', 2013. Courtesy the artist, Victoria Miro, London and Metro Pictures, New York © Isaac Julien

In the film, the crushed creative haunts his modern ruin while the harsh Icelandic landscape outside of rock and snow remains beautifully indifferent. Courtesy the artist and Victoria Miro, London © Isaac Julien.

'ICARUS DESCENDING (Playtime)', 2013. Courtesy the artist, Victoria Miro, London and Metro Pictures, New York © Isaac Julien

'THE ABYSS (Playtime)', 2013. Courtesy the artist, Victoria Miro, London and Metro Pictures, New York © Isaac Julien

Coinciding with the London shows, MoMA in New York is concurrently showing another video installation by Julien and has published 'Riot', an accompanying career retrospective

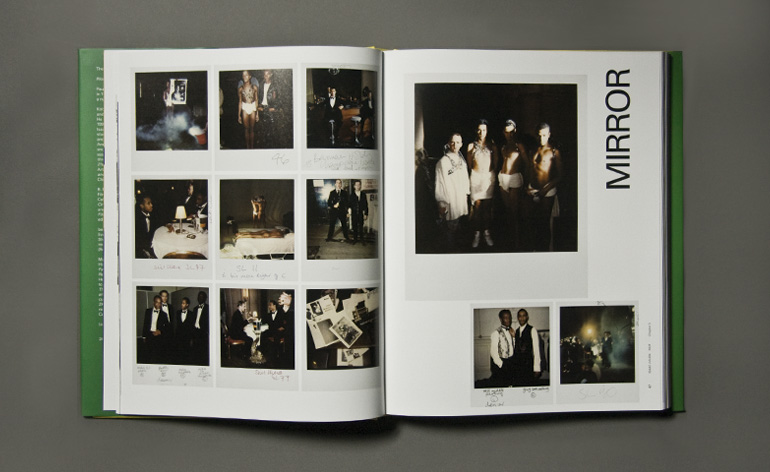

A spread from the book depicts polaroids from the set of 'Looking for Langston', by Isaac Julien, 1989

In 'ECLIPSE (Playtime)', 2013, also on show in the Victoria Miro gallery show in London, one of Julien's characters is framed, burned alive in his beautiful round window that has become a dying sun

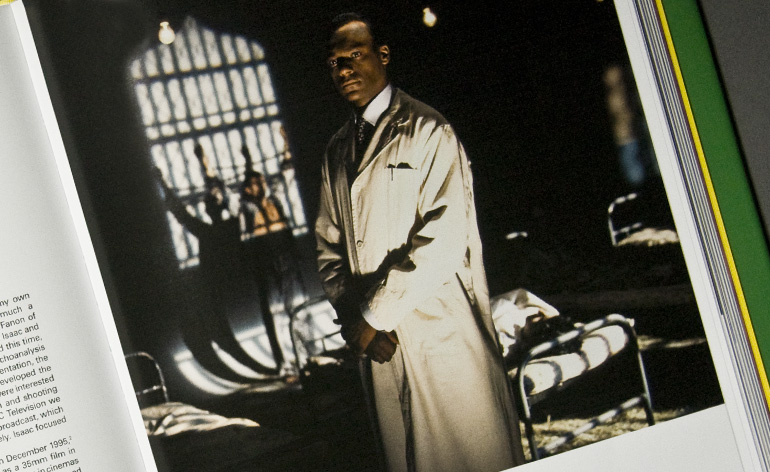

A detail of a still from 'Franz Fanon' Black Skin White Mask', 1996

A spread from the book depicts personal photographs captured by Julien in New York and London

ADDRESS

Victoria Miro

16 Wharf Rd

London N1 7RW

Victoria Miro Mayfair

14 St George Street

London W1S IFE

Wallpaper* Newsletter

Receive our daily digest of inspiration, escapism and design stories from around the world direct to your inbox.

-

Japan in Milan! See the highlights of Japanese design at Milan Design Week 2025

Japan in Milan! See the highlights of Japanese design at Milan Design Week 2025At Milan Design Week 2025 Japanese craftsmanship was a front runner with an array of projects in the spotlight. Here are some of our highlights

By Danielle Demetriou

-

Tour the best contemporary tea houses around the world

Tour the best contemporary tea houses around the worldCelebrate the world’s most unique tea houses, from Melbourne to Stockholm, with a new book by Wallpaper’s Léa Teuscher

By Léa Teuscher

-

‘Humour is foundational’: artist Ella Kruglyanskaya on painting as a ‘highly questionable’ pursuit

‘Humour is foundational’: artist Ella Kruglyanskaya on painting as a ‘highly questionable’ pursuitElla Kruglyanskaya’s exhibition, ‘Shadows’ at Thomas Dane Gallery, is the first in a series of three this year, with openings in Basel and New York to follow

By Hannah Silver

-

Celia Paul's colony of ghostly apparitions haunts Victoria Miro

Celia Paul's colony of ghostly apparitions haunts Victoria MiroEerie and elegiac new London exhibition ‘Celia Paul: Colony of Ghosts’ is on show at Victoria Miro until 17 April

By Hannah Hutchings-Georgiou

-

‘Darker, more sinister themes’: Paula Rego’s decade of self-discovery is the subject of a new London exhibition

‘Darker, more sinister themes’: Paula Rego’s decade of self-discovery is the subject of a new London exhibitionPaula Rego’s ‘Letting Loose’, at Victoria Miro in London, considers the artist’s work from the 1980s

By Hannah Silver

-

Alex Hartley’s eerie ode to Carlo Scarpa in Venice

Alex Hartley’s eerie ode to Carlo Scarpa in VeniceAlex Hartley’s theatrical new installation ‘Closer than Before’ at Victoria Miro Venice is a haunting take on architectural destruction in Venice

By Thea Hawlin

-

Stan Douglas’ riff on alternative realities has us seeing double

Stan Douglas’ riff on alternative realities has us seeing doubleCoinciding with the announcement that the Vancouver artist will represent Canada in the 2021 Venice Biennale, his galleries in New York and London are staging a dual survey of his ambitious video installation Doppelgänger

By Jessica Klingelfuss

-

Singling out the solo booths to see at Frieze Los Angeles

Singling out the solo booths to see at Frieze Los AngelesOver 70 galleries will descend on Paramount Pictures Studio for the second edition of the West Coast art fair (14-16 February), anchored by an ambitious programme of special projects, film screenings, talks, and institutional collaborations

By Jessica Klingelfuss

-

Doug Aitken’s epic art finds a home in a transformed auto repair shop in California

Doug Aitken’s epic art finds a home in a transformed auto repair shop in CaliforniaAs Doug Aitken features in the Wallpaper* 300, our guide to creative America, we revisit the surreal signage and sun-blasted landscapes of his portfolio of work, exclusively published in our November 2019 issue

By Hunter Drohojowska-Philp

-

Doug Aitken’s new show embraces real time

The American artist chimes in on the digital debate Coming soon: Wallpaper* collaborates on an exclusive project with Doug Aitken in our November 2019 issue, on sale 10 October

By Nick Compton

-

Artist Isaac Julien celebrates Brazilian architect Lina Bo Bardi on film

Artist Isaac Julien celebrates Brazilian architect Lina Bo Bardi on filmBy Nick Compton