The postwar public art that became a symbol of the British modernist dream

It’s not hard to determine where fine art photographer Simon Phipps’ expertise lies. With previous publications entitled Brutal London, Finding Brutalism and even a Brutalist London map under his belt, one could say his subject is somewhat cast in concrete. For his latest book, Concrete Poetry, Phipps has diverted his discerning lens towards prominent postwar public art and sculpture across the UK.

In the aftermath of the Second World War, Britain began rebuilding its fractured, rubble-ridden urban landscape and reestablishing societal morale. The hope of a new breed of citizen emerged, one that was community-minded, liberal and embraced the largely uncharted territory of communal living spaces.

This was a municipal renaissance: 27 new towns sprung up across the British Isles and existing city centres were revived and remodelled. With it came an era in which the function of publicly owned art came to the fore as symbols of creative democracy, emblems of Britain in the midst of progression and in the Phipps’ words, totems for ‘shared social experiences’.

Marking the first photographic examination of modernist sculpture within a brutalist context, the book both rejoices in and laments for work commissioned and created during this period, much of which has since been lost, vandalised or destroyed entirely. ‘Many of these works have a sense of “rightness” in their location,’ Phipps reflects in his introduction, ‘a feeling of belonging that can sometimes mean a certain invisibility, often as a result of a normality engendered over time.’

Untitled Sculpture, 1967, by Jim Barclay. Baths Hill, East Kilbride, Glasgow. Unlisted. East Kilbride was the first of five postwar new towns designated to alleviate housing shortages in Scotland. It was planned with a comprehensive programme of modern buildings augmented by public sculpture.

The author visually dissects the role of this sculptural revolution and in turn, recognises the tangible impact of these offerings on the wider socio-political landscape. From County Durham to Glasgow, down to Leicestershire and West to Cardiff, the author traces a broad litany of work found in the nooks and crannies of urban and suburban Britain. These include British-German designer Bernard Schottlander’s vibrant 2MS Series No. 4 (1970), a quartet of chromatically vibrant structures sliced at sharp angles in situ in the Fred Roche Gardens in Phipps’ native Milton Keynes.

With an untitled work in 1968, British architect Peter Womersley foreshadowed the impending postmodernist era with his linear geometry fused with semi-circular motifs. This was commissioned for the world’s first purpose-built organ transplantation unit, documented by Phipps in Edinburgh’s Western General Hospital.

Three Obliques (Walk-In) is a 1968 work by British sculptural doyenne Barbara Hepworth for Cardiff University’s School of Music. The artist deploys her signature ‘pierced forms’ in this this harmonious trio of bronze slabs – a structure that demands active engagement, or as Hepworth herself artfully advised, ‘You can’t look at a sculpture if you are going to stand stiff as a ramrod and stare at it.’

Phipps has compiled yet another weighty tome deeper than aesthetics and broader than brutalism. One thing Concrete Poetry resoundingly reaffirms is that brutalist sculpture continues to be as divisive as it is entrenched in the familiar landscape of postwar Britain.

Declaration, 1961, by Phillip King. Beaumanor Hall, Beaumanor Drive, Woodhouse, Loughborough. Listed, Grade II

Declaration marks a point in both King’s artistic development and that of modern British sculpture. One of the first non-figurative works King produced, it has been proposed as the first instance of a British sculptural composition based on repetition of non-organic forms. Originally cast in green cement (the colour now eroded), it was purchased by Leicester Education Authority and installed at Stonehill High School. In the 1990s it was moved to Beaumanor Hall, which the county council runs as a conference venue.

Three Obliques (Walk-In), 1968, by Barbara Hepworth. School of Music, Cardiff University, Corbett Road, Cardiff. Unlisted

Contrary to her usual practice, Hepworth made a small-scale version of Three Obliques, to be cast in bronze, before working it as a monumental piece. As such, it deliberately invites an active engagement – ‘you can’t look at a sculpture if you are going to stand stiff as a ramrod and stare at it,’ Hepworth urged, ‘you must walk around it, bend toward it, touch it and walk away from it.’

Concrete Sculpture, 1976-77, by Charles Anderson. Bannerman High School, Baillieson, Glasgow. Unlisted

Details of the commissioning of this work by Charles Anderson are not known. Twin blocks of in situ cast concrete, one lying horizontal and one upright, feature the swirling circular motifs that can be seen in other sculptural relief works by Anderson. It stands at the entrance to Bannerman High School and, like many public artworks of its kind, seems to have become absorbed into the anonymous landscape of the school. ‘I don’t really notice it at all,’ remarked one member of staff.

2MS Series No. 4, 1970, by Bernard Schottlander. Fred Roche Gardens, Silbury Boulevard, Milton Keynes. Listed, Grade II

The Milton Keynes Development Corporation’s ambitious commissioning programme has gifted the new town with over 200 public artworks. After Schottlander’s 1972 solo show in London, the corporation purchased four of his sculptures. Possessed of a buoyant pop sensibility, these monumental works in painted welded steel were originally installed in the grounds of the corporation’s Wavendon Tower headquarters, but in 1983 were distributed around the city. 2MS Series No. 4, a quartet of orthogonal elements sliced at an angle, stands with two other Schottlander sculptures in Fred Roche Gardens.

Extrapolation, 1982, by Liliane Lijn. Library of East Anglia University, Norwich. Unlisted

Extrapolation was the winning sculpture of the Norwich Triennial Festival Sculpture Competition in 1982. The brief was to design a sculpture for the inner courtyard of the Norwich Central Library. Lijn played with the idea of layers or leaves as in the pages of a book. In 1992, the sculpture was re-sited in a garden in front of the Grade II-listed Library of East Anglia University.

Wallpaper* Newsletter

Receive our daily digest of inspiration, escapism and design stories from around the world direct to your inbox.

Nuffield Transplantation Surgery Unit, 1968, by Peter Womersley. Western General Hospital, Edinburgh. Unlisted

Womersley may well be one of brutalism’s best-kept secrets. His charismatic design for the world’s first purpose-built organ transplantation unit lends emphatic presence to a pioneering medical establishment and embodies the platonic geometries and uncompromising technical rigour of high modernism. At the same time, this profoundly sculptural concrete structure has a mannerist quality that seems almost to hint at a postmodernism yet to come.

Kingsway Tunnel Vents, 1971, by Edmund Nuttall Ltd. Liverpool. Unlisted

Designed to relieve congestion in the existing Birkenhead and Queensway tunnels beneath the Mersey, the Kingsway Tunnel was constructed by Liverpool civil engineers Edmund Nuttall Ltd (the firm responsible the Liver Building), and opened in 1971. The ventilation shafts standing on either bank of the Mersey are a forceful expression of technological achievement, positively flamboyant in their uncompromising modernity. Unconscious, possibly, but they also hint at the profile of city’s other ‘Mersey Funnel’, the Metropolitan Cathedral.

Avila, 1975, by Bryan Kneale. Bosworth Academy, Leicester Lane, Desford, Leicestershire. Unlisted

Kneale was the first abstract sculptor to be elected to the Royal Academy, an honour he refused to accept unless the institution staged a show of contemporary British sculpture. The resulting landmark exhibition, ‘British Sculptors ‘72’, showcased the work of Eduardo Paolozzi, Phillip King, Geoffrey Clarke and others. Avila, formed from tubular and flat steel elements, braced against each other, and painted blue, mustard and purple, stands in front of the former community college, now an academy specialising in sport.

Callanish, 1974, by Gerald Laing. Wolfson Centre, University of Strathclyde, Glasgow. Unlisted

Often (erroneously) referred to as ‘Steelhenge’, Callanish in fact references the standing stones of the Western Isles and was designed, the artist noted, ‘to remind the scientifically orientated student that there is a place for the contemplative – and the art student that art must make use of modern scientific materials and scales to remain relevant’. This ring of Corten steel elements, rising stark and sheer from a lawn, was jointly funded by the University of Strathclyde and the Scottish Arts Council.

Abstract Wall Relief, 1972, by Keith McCarter. Charing Cross, Glasgow. Unlisted

This bold mural, composed of 19 precast concrete blocks, was commissioned as part of a development centred on an office block, and forms part of the walkway to Glasgow’s Charing Cross railway station. Each of the mural’s blocks is approximately 1.3m wide, and the advancing and receding of alternate planes creates space for a variety of textural effects.

INFORMATION

Concrete Poetry: Post-War Modernist Public Art, £20, published by September Publishing. For more information, visit Simon Phipps’ website

Harriet Lloyd-Smith was the Arts Editor of Wallpaper*, responsible for the art pages across digital and print, including profiles, exhibition reviews, and contemporary art collaborations. She started at Wallpaper* in 2017 and has written for leading contemporary art publications, auction houses and arts charities, and lectured on review writing and art journalism. When she’s not writing about art, she’s making her own.

-

From dress to tool watches, discover chic red dials

From dress to tool watches, discover chic red dialsWatch brands from Cartier to Audemars Piguet are embracing a vibrant red dial. Here are the ones that have caught our eye.

-

Behind a contemporary veil, this Kyoto house has tradition at its core

Behind a contemporary veil, this Kyoto house has tradition at its coreDesigned by Apollo Architects & Associates, a Kyoto house in Uji City is split into a series of courtyards, adding a sense of wellbeing to its residential environment

-

EV maker Rivian creates its first Concept Experience in New York’s Meatpacking District

EV maker Rivian creates its first Concept Experience in New York’s Meatpacking DistrictUnder the High Line, in the heart of one of New York’s most famous neighbourhoods is the Rivian Concept Experience, a showroom designed to surprise and delight both long-term aficionados and total newcomers to the brand

-

Inside Yinka Shonibare's first major show in Africa

Inside Yinka Shonibare's first major show in AfricaBritish-Nigerian artist Yinka Shonibare is showing 15 years of work, from quilts to sculptures, at Fondation H in Madagascar

-

Ai Weiwei’s new public installation is coming soon to Four Freedoms State Park

Ai Weiwei’s new public installation is coming soon to Four Freedoms State Park‘Camouflage’ by Ai Weiwei will launch the inaugural Art X Freedom project in September 2025, a new programme to investigate social justice and freedom

-

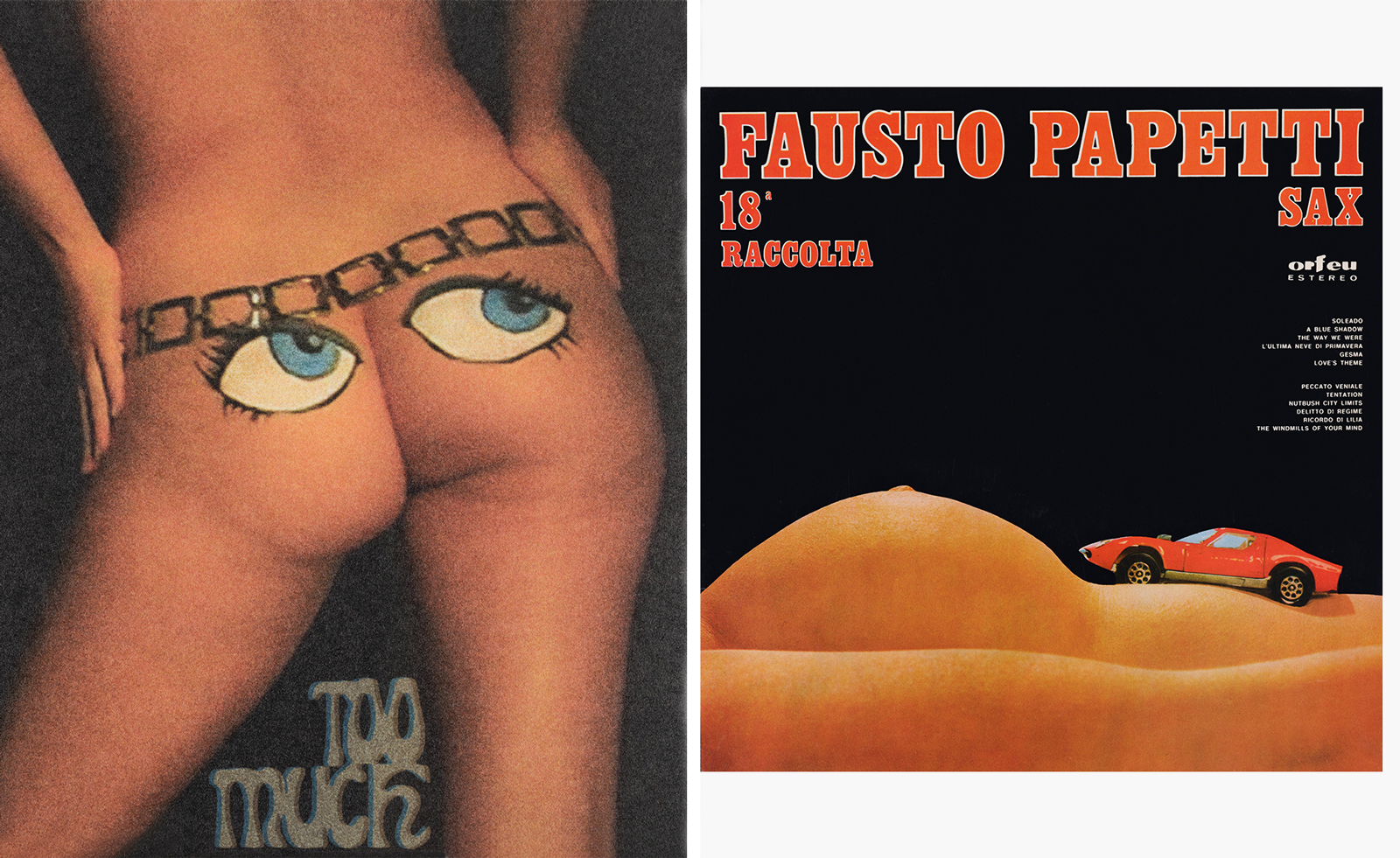

Taschen’s sexy record covers are hitting all the right notes

Taschen’s sexy record covers are hitting all the right notesTaschen has been through 50 years of album art for its latest tome, ‘Sexy Record Covers’

-

Meet the Turner Prize 2025 shortlisted artists

Meet the Turner Prize 2025 shortlisted artistsNnena Kalu, Rene Matić, Mohammed Sami and Zadie Xa are in the running for the Turner Prize 2025 – here they are with their work

-

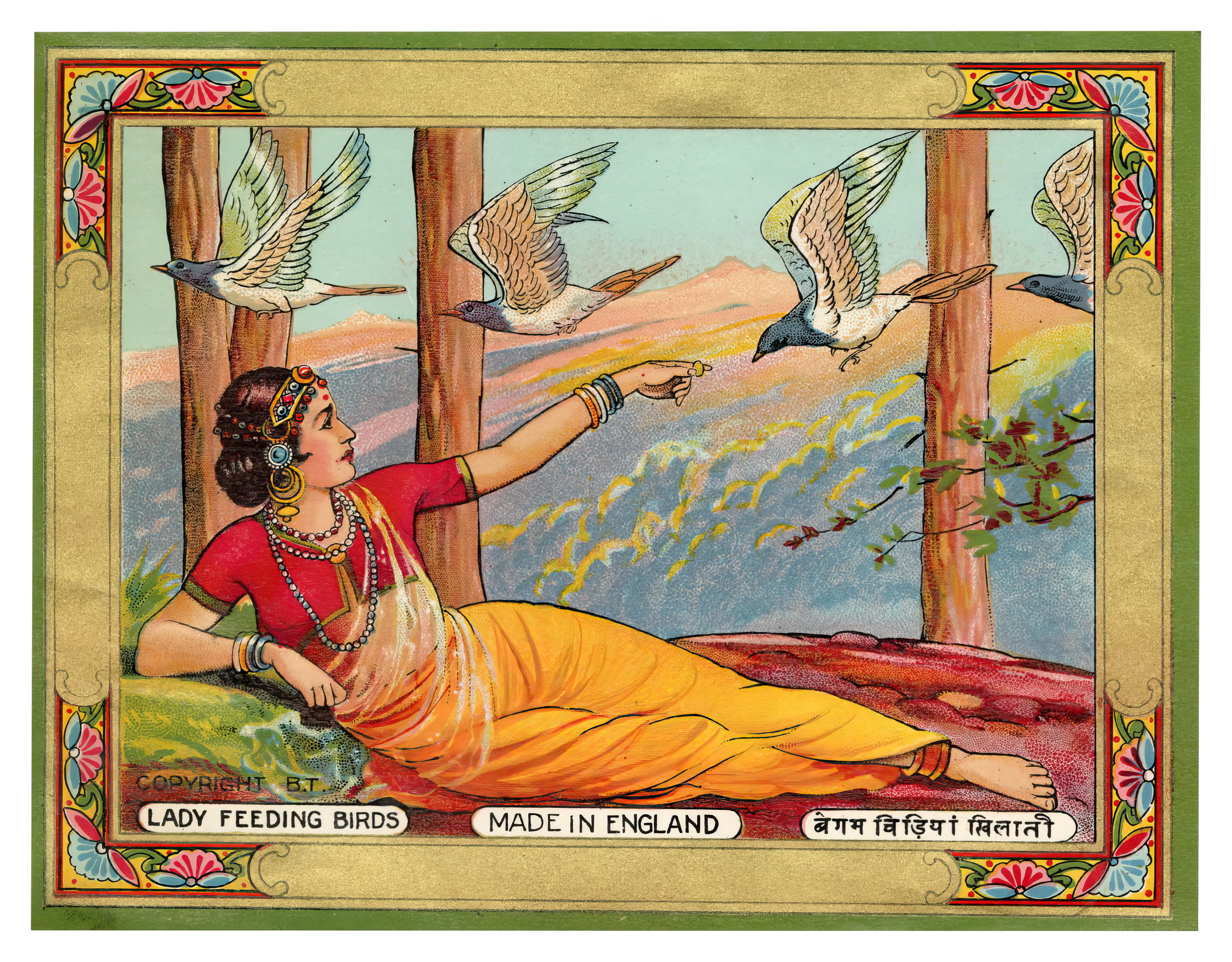

The art of the textile label: how British mill-made cloth sold itself to Indian buyers

The art of the textile label: how British mill-made cloth sold itself to Indian buyersAn exhibition of Indo-British textile labels at the Museum of Art & Photography (MAP) in Bengaluru is a journey through colonial desire and the design of mass persuasion

-

‘Dressed to Impress’ captures the vivid world of everyday fashion in the 1950s and 1960s

‘Dressed to Impress’ captures the vivid world of everyday fashion in the 1950s and 1960sA new photography book from The Anonymous Project showcases its subjects when they’re dressed for best, posing for events and celebrations unknown

-

From counter-culture to Northern Soul, these photos chart an intimate history of working-class Britain

From counter-culture to Northern Soul, these photos chart an intimate history of working-class Britain‘After the End of History: British Working Class Photography 1989 – 2024’ is at Edinburgh gallery Stills

-

This rainbow-coloured flower show was inspired by Luis Barragán's architecture

This rainbow-coloured flower show was inspired by Luis Barragán's architectureModernism shows off its flowery side at the New York Botanical Garden's annual orchid show.