Rana Begum’s minimalist art toys with light, colour and space

We explore the work of Rana Begum, which is enmeshed with beauty, vibrancy and architecture, and step inside the artist’s epic new north London studio

Olivia Arthur - Photography

Rana Begum and fashion designer Roksanda Ilinčić’s first collaboration consisted of a web of coloured fishing nets spun across the Giles Gilbert Scott-designed Durbar Court, the stodgy heart of the UK government’s Foreign Office. Carving up the lofty inner sanctum, the luminescent nets shot across three storeys of columns and landed on the marble floor to form a prismatic set for Roksanda’s A/W 2022 collection. Begum, an artist fascinated with interplays between light, colour and space, seemingly met her creative kith and kin in Ilinčić, a designer revered for her colour-block, ballooning sculptural pieces. It’s been a long-standing admiration, ‘even before our collaboration’, says Ilinčić. ‘Very cheekily, I used one of her Folded Grid series as inspiration for my pre-fall 2019 collection. You could see this wonderful aura of pinkness floating around it.’

Embedded within both practices is the experience and appreciation of architectural principles. While Ilinčić was privy to the concrete socialist landscape of her hometown of Belgrade, Serbia, Begum admired the impressive Indo-Islamic buildings during her childhood in Sylhet, Bangladesh. And movement around, through, out of and into space brought the pair together again this year for a public commission for The Line, a sculpture trail in east London. No.1104 Catching Colour, a floating plume of sherbety colour, stretches out in the centre of City Island’s Botanic Square, encircled by high-rise flats.

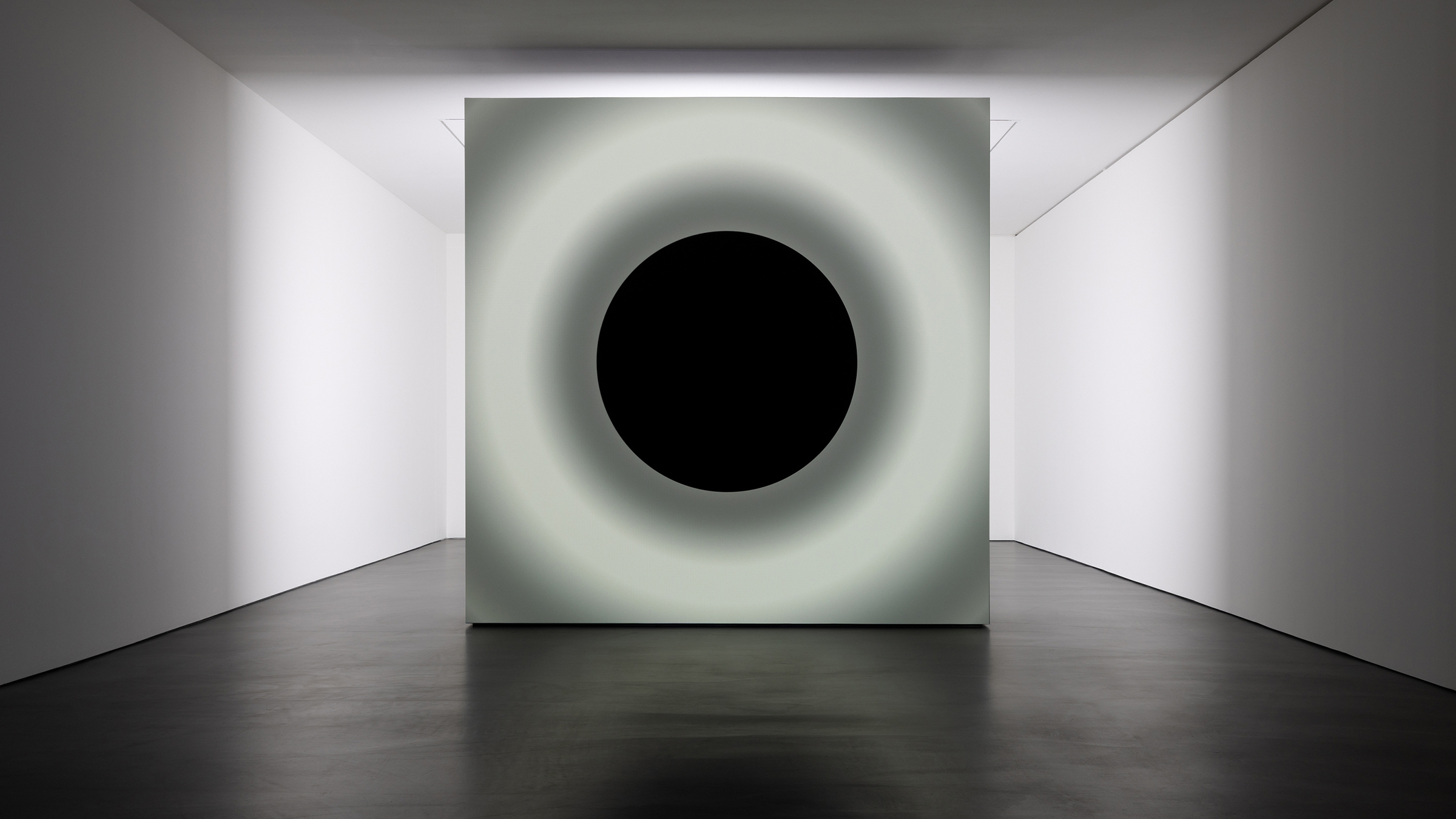

Rana Begum, No. 1081 Mesh © Begum Studio.

The work was launched with a performance by the English National Ballet, choreographed by Stina Quagebeur. Ilinčić dressed the dancers in close-fitting costumes, characteristically bold in their palette. ‘It was new to me,’ explains Begum. ‘The piece is like a conversation between Roksanda, Stina and me.’ Underneath Begum’s cumulus puff of pigment – deceptively spongey although formed from metal mesh – dancers moved through the air, as dashes of pigment flew with them. A light breeze and the work softly swayed.

The chameleonic sculpture, like the best of Begum’s work, shifts with its environment and its viewer’s position. Exposed to the elements, the layers of lattice absorb and deflect light; colours intensify and shadows pattern the ground beneath it, evoking light streaming through a jali. A similar sculpture is installed at west London’s Pitzhanger Manor & Gallery as part of Begum’s touring exhibition, ‘Dappled Light’. Suspended underneath an original 19th-century circular skylight, the cluster of metal scrunches ushers shards of light onto the glossy floor of the gallery. The manor house was designed by John Soane, a man who considered light his building material. ‘This connection with Soane and the way he plays with light, and brings it into the space, was really exciting,’ Begum enthuses, with the caveat that there were challenges. ‘The house is listed and you can’t touch the walls.’ Instead, Begum’s work spreads into the stairwell and onto the balcony.

Rana Begum with No.1149 Folded Grid (2022), spray paint on Jesmonite

The show has travelled from Warwick’s recently refurbished Mead Gallery, and will continue on to The Box in Plymouth. Curated by Cliff Lauson, the new director of exhibitions at Somerset House, the show emphasises that, in her exploration of light, Begum can be fickle with her mediums. She leaps from steel nodules inspired by Istanbul’s rooftops, to totems made of vehicle reflectors first set upon during a residency in Bangkok, to chevron watercolours that evoke the work of painter Tess Jaray, an early mentor.

Begum’s clarity of focus transcends the abundance of colour, materials and forms. Each work is numbered, suggesting an infinite continuum and relentlessness in her experimentation with light. There are steadfast motifs, such as her predilection for grids and sharp lines seen in the crisp Donald Judd-like bars of her wall-based works, and the colour-changing prints for her recent solo show with Cristea Roberts Gallery. With light as its founding principle, the work imbues rudimentary objects with majesty. Begum has turned singular forms into light-filtering composites; for instance, joining handwoven bamboo baskets to become cavernous hollow spaces that draw in light through their warps and wefts. For a project at Wanås Konst in Sweden last year, a pyramid of terracotta pipes, floating on water, funnelled sunlight through their apertures.

Detail of a mesh element from a work in progress

Begum’s studio-home in north London speaks of the same ethos; the space is a vessel for light. The project, which its designer Peter Culley, of Spatial Affairs Bureau, calls a ‘retreat compound’, has transformed the former ‘asbestos-covered shed’ into a three-floor space, with adjoining flat, to accommodate her family, studio team, resident artists and a timeline heaving with exhibitions and commissions. The open-plan interior is crafted around skylights and windows that frame the trees of Abney Park Cemetery. The view of this local nature reserve is the basis of Begum’s first video work, No.1080 Forest (2021). Made during lockdown, it’s a slow study of the seasons passing through the dense canopy.

Wallpaper* Newsletter

Receive our daily digest of inspiration, escapism and design stories from around the world direct to your inbox.

‘I’ve always hated the idea of barriers and fencing,’ says Begum. So the studio’s entrance is opened up to the park, with a sculpture court and courtyard garden that brush up to the cemetery’s boundary wall and siphon off its tranquillity. For Begum, barriers are emblematic of social neurosis. ‘What is it that gates allow you to do? They push people out, but at the same time they make you feel secure.’ This is a paradox Begum will take up in an upcoming New York project with the Art Production Fund. And similar ideas around permissible flows of movement and security are acknowledged in her co-curation of the architectural section of the Royal Academy Summer Exhibition with architect Níall McLaughlin. The focal point is Khudi Bari, a flood shelter on bamboo stilts designed for Rohingya refugees by architect Marina Tabassum. The two women have previously worked together and no doubt will do again, for, as Begum explains: ‘As artists, you can isolate yourself quite a bit, and become quite stale in the way you look at things. It’s really interesting to hear a different perspective.’

Begum and studio assistant Zara Ramsay with No.1124 Reflector Tower (2022)

Begum’s models line the plywood shelves of her London studio

Begum in her studio, designed in collaboration with Peter Culley of Spatial Affairs Bureau

INFORMATION

Rana Begum, ’Dappled Light’, until 11 September 2022, Pitzhanger Manor, London. pitzhanger.org.uk

-

Meet Lisbeth Sachs, the lesser known Swiss modernist architect

Meet Lisbeth Sachs, the lesser known Swiss modernist architectPioneering Lisbeth Sachs is the Swiss architect behind the inspiration for creative collective Annexe’s reimagining of the Swiss pavilion for the Venice Architecture Biennale 2025

By Adam Štěch

-

A stripped-back elegance defines these timeless watch designs

A stripped-back elegance defines these timeless watch designsWatches from Cartier, Van Cleef & Arpels, Rolex and more speak to universal design codes

By Hannah Silver

-

Postcard from Brussels: a maverick design scene has taken root in the Belgian capital

Postcard from Brussels: a maverick design scene has taken root in the Belgian capitalBrussels has emerged as one of the best places for creatives to live, operate and even sell. Wallpaper* paid a visit during the annual Collectible fair to see how it's coming into its own

By Adrian Madlener

-

Remote Antarctica research base now houses a striking new art installation

Remote Antarctica research base now houses a striking new art installationIn Antarctica, Kyiv-based architecture studio Balbek Bureau has unveiled ‘Home. Memories’, a poignant art installation at the remote, penguin-inhabited Vernadsky Research Base

By Harriet Lloyd-Smith

-

Ryoji Ikeda and Grönlund-Nisunen saturate Berlin gallery in sound, vision and visceral sensation

Ryoji Ikeda and Grönlund-Nisunen saturate Berlin gallery in sound, vision and visceral sensationAt Esther Schipper gallery Berlin, artists Ryoji Ikeda and Grönlund-Nisunen draw on the elemental forces of sound and light in a meditative and disorienting joint exhibition

By Harriet Lloyd-Smith

-

Cecilia Vicuña’s ‘Brain Forest Quipu’ wins Best Art Installation in the 2023 Wallpaper* Design Awards

Cecilia Vicuña’s ‘Brain Forest Quipu’ wins Best Art Installation in the 2023 Wallpaper* Design AwardsBrain Forest Quipu, Cecilia Vicuña's Hyundai Commission at Tate Modern, has been crowned 'Best Art Installation' in the 2023 Wallpaper* Design Awards

By Harriet Lloyd-Smith

-

Michael Heizer’s Nevada ‘City’: the land art masterpiece that took 50 years to conceive

Michael Heizer’s Nevada ‘City’: the land art masterpiece that took 50 years to conceiveMichael Heizer’s City in the Nevada Desert (1972-2022) has been awarded ‘Best eighth wonder’ in the 2023 Wallpaper* design awards. We explore how this staggering example of land art came to be

By Harriet Lloyd-Smith

-

Cerith Wyn Evans: ‘I love nothing more than neon in direct sunlight. It’s heartbreakingly beautiful’

Cerith Wyn Evans: ‘I love nothing more than neon in direct sunlight. It’s heartbreakingly beautiful’Cerith Wyn Evans reflects on his largest show in the UK to date, at Mostyn, Wales – a multisensory, neon-charged fantasia of mind, body and language

By Harriet Lloyd-Smith

-

The best 7 Christmas installations in London for art lovers

The best 7 Christmas installations in London for art loversAs London decks its halls for the festive season, explore our pick of the best Christmas installations for the art-, design- and fashion-minded

By Harriet Lloyd-Smith

-

Rafael Lozano-Hemmer’s Pulse Topology in Miami is powered by heartbeats

Rafael Lozano-Hemmer’s Pulse Topology in Miami is powered by heartbeatsRafael Lozano-Hemmer brings heart and human connection to Miami Art Week 2022 with Pulse Topology, an interactive light installation at Superblue Miami in collaboration with BMW i

By Fiona Mahon

-

Textile artists: the pioneers of a new material world

Textile artists: the pioneers of a new material worldThese contemporary textile artists are weaving together the rich tapestry of fibre art in new ways

By Harriet Lloyd-Smith