All about Saul Leiter, the zen master of street photography

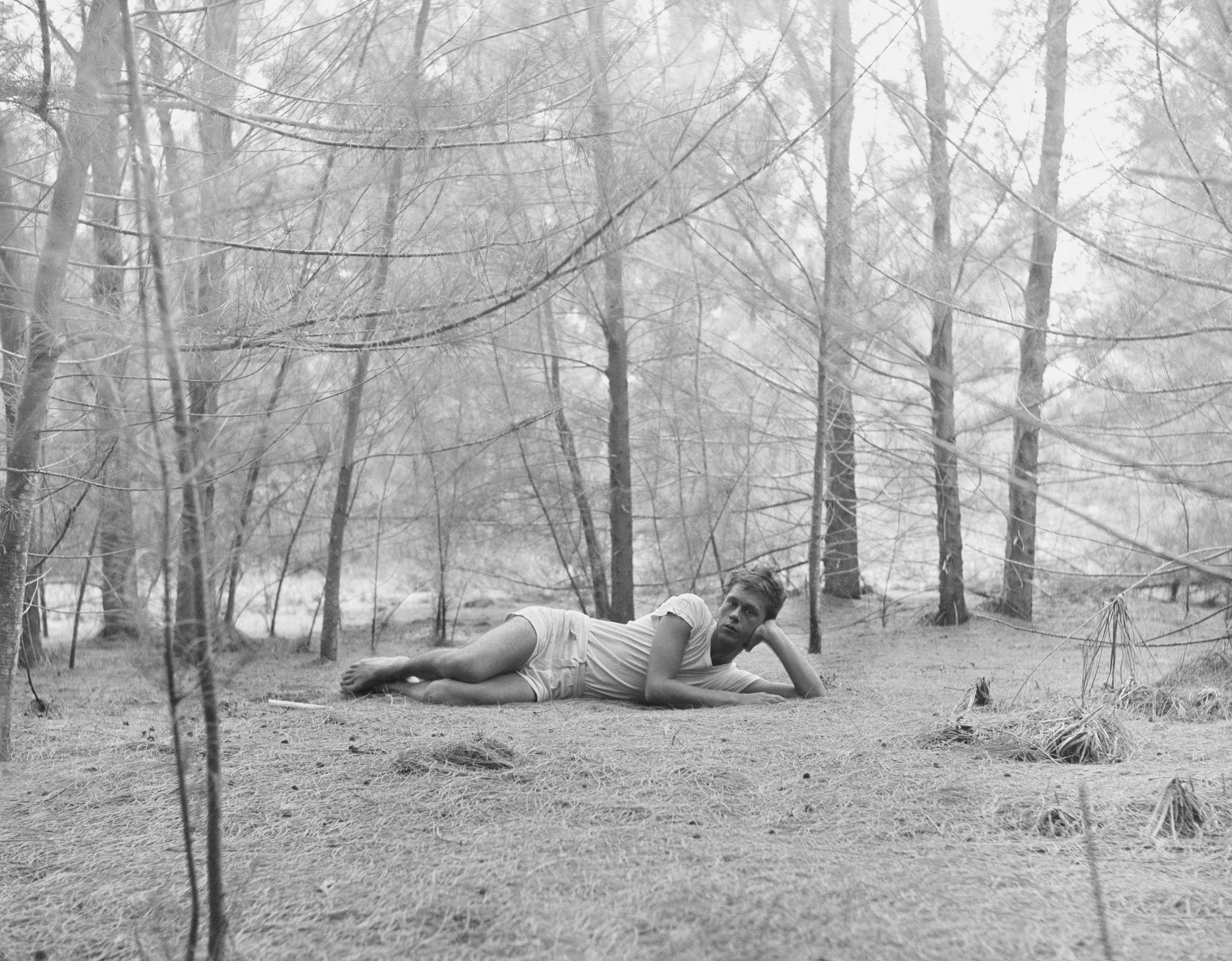

Saul Leiter was born in 1923 in Pittsburgh, the son of a renowned Jewish theological scholar. His family expected him to follow his father – to attend theology school and become a Rabbi. Leiter dutifully did so, spending his early twenties immersed in the teachings of the Talmud at a theology school in Cleveland.

But an interest in another kind of deity kept pulling at him. Leiter was fascinated by abstract art, and, at the age of 23, to the horror of his devout family, he dropped out of theology school, got the bus to New York, found a home in the Manhattan’s East Village and enrolled in art school.

Leiter’s early paintings are awash with colour, in the lineage of expressionists like Willem de Kooning or Franz Kline and impressionists like Pierre Bonnard and Édouard Vuillard. He became immersed in the ornate minimalism of Japanese art, particularly the revolutionary ukiyo-e printmakers of the 18th and 19th centuries. Names like Hokusai, Tawaraya Sōtatsu and Hon’ami Kōetsu, with their use of calligraphy, block statements of colour, and ma – a Japanese spatial concept of negative space, ‘the nothingness where, infact, everything happens’, as the Japanese historian Kōtarō Iizawa terms it.

Through his classes, he befriended the painter Richard Pousette-Dart, an abstract expressionist who was on social terms with the photographer W Eugene Smith. The American photojournalist, in turn, opened Leiter up to a circle of friends and rivals – the founding members of the humanist photographic movement known as the New York School of Photography; Robert Frank, William Klein, Richard Avedon and Diane Arbus. Photography, Leiter decided, was how he would dedicate his time.

Postmen, 1952, by Saul Leiter. © Saul Leiter Foundation. Courtesy of Howard Greenberg Gallery

Until his death at the age of 90, on November 26, 2013, Leiter was not well known beyond industry circles. He worked for fashion magazines – most notably Vogue and Elle – and gained photojournalistic commissions throughout much of his life. But he was never renowned or celebrated as a great visual artist in the way Arbus or Frank are.

Indeed, the photography industry was not always kind to him. In the early 1980s, Leiter found it more and more difficult to find work. He fell into debt, and had to sell-off the studio he had always used on Fifth Avenue. It sparked a withdrawal from public life, and for much of the rest of his days, he lived and worked in a reclusive, solitary fashion.

Leiter’s apartment was near Saint Mark’s Place. He lived there for the entirety of his life in New York, and the vast majority of the many thousands of photographs he took of the city were taken within two blocks of his home. There’s an irony here, for, while he would never have known it when he first moved in, Saint Mark’s Place gradually became Little Tokyo – one of the largest communities of Japanese people living anywhere beyond the homeland.

It is this private, personal photography that is leading to a reappraisal of Leiter’s work. As a new monograph by Thames & Hudson attests, Leiter should be remembered as one the great pioneers in the history of photography – a bedrock for anyone interested in how colour can be arranged in a frame.

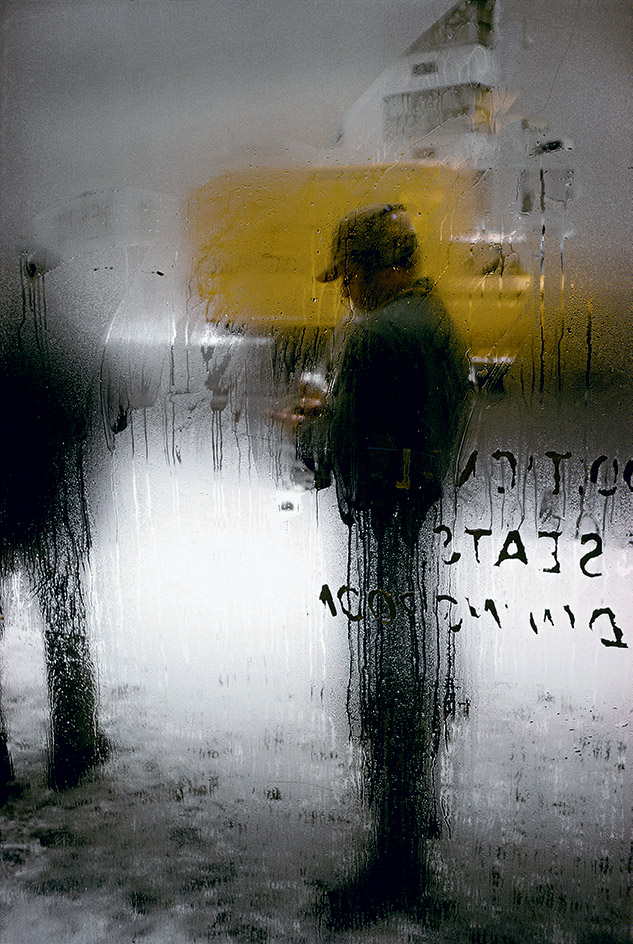

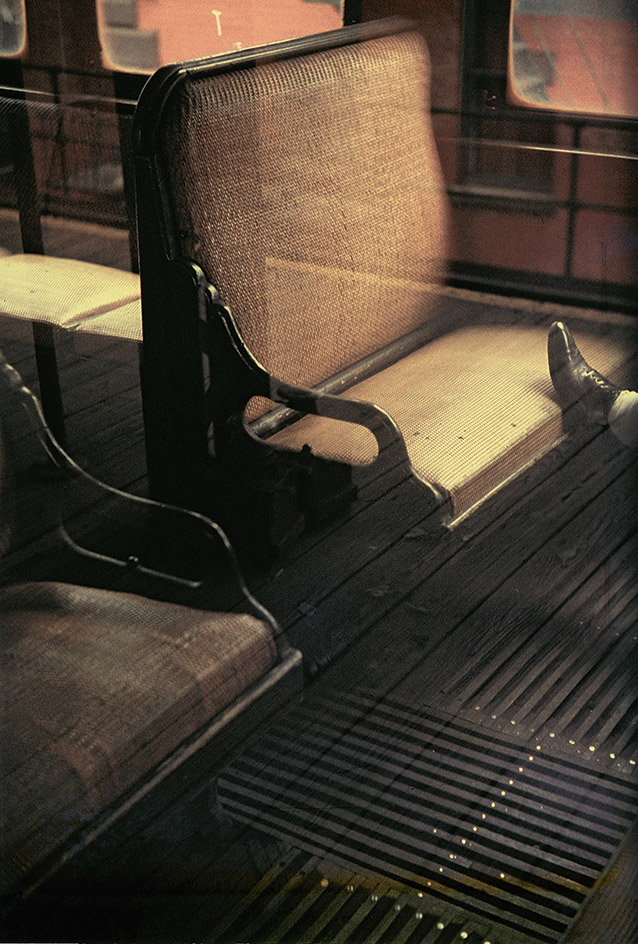

Leiter used an inexpensive 35mm camera, and would purposefully shoot with aged or environmentally-damaged film. He used the smoke that snaked from the city’s pavements, or the steam that collects on the windows of a cafe, or the churned snow on the streets, as ways to manipulate the saturation of light, the contrasts of focus, and the sheen and tone of colour of his photographs. He would use oblique angles, or push the more human elements of the image to the edges of the frame. Rather than focus on the expression of someone’s face, he would hone in on the red of an umbrella, the green of a traffic light or the yellow of a passing taxi as the gravitational epicentre of his images.

As such, and unlike his New York School contemporaries, Leiter wasn’t a classically humanist photographer. He didn’t seem that interested in using his camera as an instrument for social change or moral imperatives. Instead, his photography can best be understood as quasi-abstract, more concerned with compositions of light and interpretations of geometry.

And, as Pauline Vermare writes in the new monograph, this might be understood through Leiter’s belief in a very Japanese concept: ‘Saul lived in accordance with the mayor zen principle of not attaching any great significance to himself, or even his art, and having no defined purpose or intent in life except for being present to the world and always highly aware of its fleeting beauty,’ Vermare writes. ‘Not preaching, just looking.’

Snow, 1960, by Saul Leiter. © Saul Leiter Foundation. Courtesy of Howard Greenberg Gallery

Don’t Walk, 1952, by Saul Leiter. © Saul Leiter Foundation. Courtesy of Howard Greenberg Gallery

Haircut, 1956, by Saul Leiter. © Saul Leiter Foundation. Courtesy of Howard Greenberg Gallery

Foot on El, 1954, by Saul Leiter. © Saul Leiter Foundation. Courtesy of Howard Greenberg Gallery

INFORMATION

All About Saul Leiter, £19.95, published by Thames & Hudson

Receive our daily digest of inspiration, escapism and design stories from around the world direct to your inbox.

Tom Seymour is an award-winning journalist, lecturer, strategist and curator. Before pursuing his freelance career, he was Senior Editor for CHANEL Arts & Culture. He has also worked at The Art Newspaper, University of the Arts London and the British Journal of Photography and i-D. He has published in print for The Guardian, The Observer, The New York Times, The Financial Times and Telegraph among others. He won Writer of the Year in 2020 and Specialist Writer of the Year in 2019 and 2021 at the PPA Awards for his work with The Royal Photographic Society. In 2017, Tom worked with Sian Davey to co-create Together, an amalgam of photography and writing which exhibited at London’s National Portrait Gallery.

-

Year in review: the shape of mobility to come in our list of the top 10 concept cars of 2025

Year in review: the shape of mobility to come in our list of the top 10 concept cars of 2025Concept cars remain hugely popular ways to stoke interest in innovation and future forms. Here are our ten best conceptual visions from 2025

-

These Guadalajara architects mix modernism with traditional local materials and craft

These Guadalajara architects mix modernism with traditional local materials and craftGuadalajara architects Laura Barba and Luis Aurelio of Barbapiña Arquitectos design drawing on the past to imagine the future

-

Robert Therrien's largest-ever museum show in Los Angeles is enduringly appealing

Robert Therrien's largest-ever museum show in Los Angeles is enduringly appealing'This is a Story' at The Broad unites 120 of Robert Therrien's sculptures, paintings and works on paper

-

Inside the seductive and mischievous relationship between Paul Thek and Peter Hujar

Inside the seductive and mischievous relationship between Paul Thek and Peter HujarUntil now, little has been known about the deep friendship between artist Thek and photographer Hujar, something set to change with the release of their previously unpublished letters and photographs

-

Nadia Lee Cohen distils a distant American memory into an unflinching new photo book

Nadia Lee Cohen distils a distant American memory into an unflinching new photo book‘Holy Ohio’ documents the British photographer and filmmaker’s personal journey as she reconnects with distant family and her earliest American memories

-

Out of office: The Wallpaper* editors’ picks of the week

Out of office: The Wallpaper* editors’ picks of the weekThe rain is falling, the nights are closing in, and it’s still a bit too early to get excited for Christmas, but this week, the Wallpaper* team brought warmth to the gloom with cosy interiors, good books, and a Hebridean dram

-

Inside Davé, Polaroids from a little-known Paris hotspot where the A-list played

Inside Davé, Polaroids from a little-known Paris hotspot where the A-list playedChinese restaurant Davé drew in A-list celebrities for three decades. What happened behind closed doors? A new book of Polaroids looks back

-

Ed Ruscha’s foray into chocolate is sweet, smart and very American

Ed Ruscha’s foray into chocolate is sweet, smart and very AmericanArt and chocolate combine deliciously in ‘Made in California’, a project from the artist with andSons Chocolatiers

-

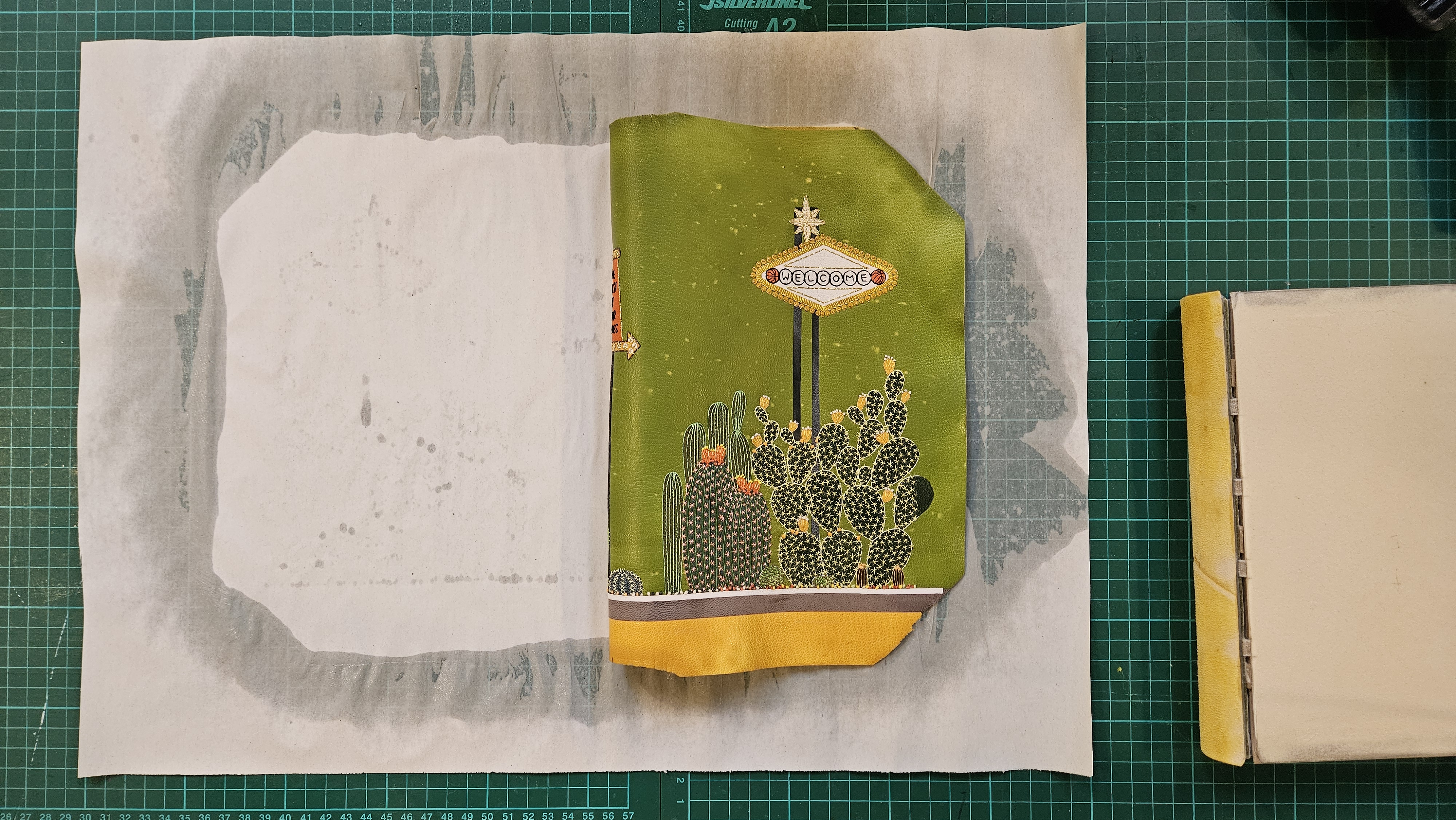

Inside the process of creating the one-of-a-kind book edition gifted to the Booker Prize shortlisted authors

Inside the process of creating the one-of-a-kind book edition gifted to the Booker Prize shortlisted authorsFor over 30 years each work on the Booker Prize shortlist are assigned an artisan bookbinder to produce a one-off edition for the author. We meet one of the artists behind this year’s creations

-

Out of office: The Wallpaper* editors’ picks of the week

Out of office: The Wallpaper* editors’ picks of the weekThis week, the Wallpaper* editors curated a diverse mix of experiences, from meeting diamond entrepreneurs and exploring perfume exhibitions to indulging in the the spectacle of a Middle Eastern Christmas

-

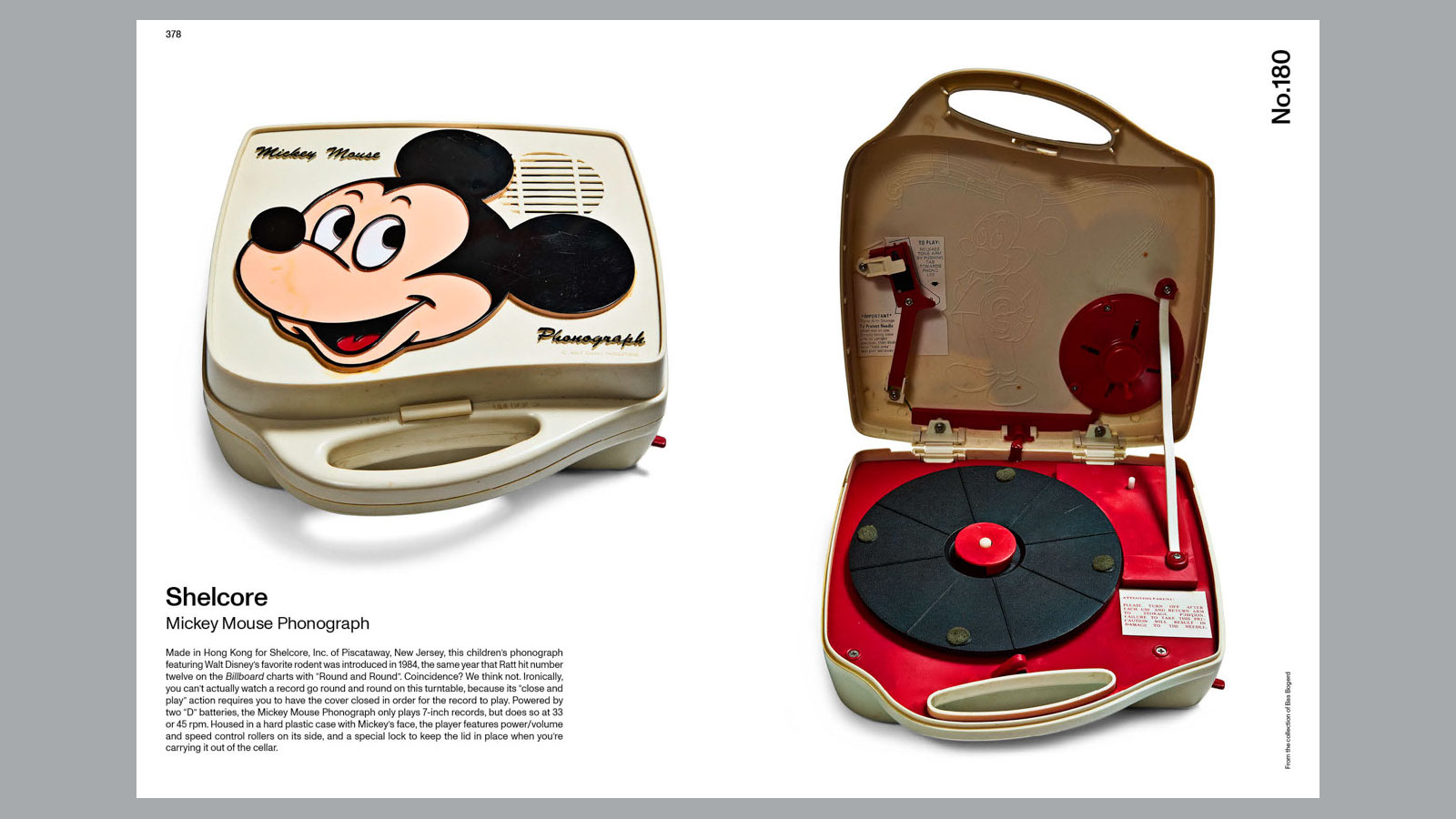

14 of the best new books for music buffs

14 of the best new books for music buffsFrom music-making tech to NME cover stars, portable turntables and the story behind industry legends – new books about the culture and craft of recorded sound