Shaping light through photography and abstract art at Tate Modern

Tate Modern in London has unveiled an extensive exhibition celebrating the parallel evolution of photography and abstract art, voiced through more than 350 sculptures, paintings, installations and photographs created by over 100 artists. ‘Shape of Light: 100 Years of Photography and Abstract Art’ offers a detailed commentary on work from 1910 to now, highlighting how both fields first formed and evolved, spurring each other on in the process.

Overseen by Simon Baker, senior curator at Tate Modern, Emmanuelle d’Ecotais, curator for photography at the Musée d’Art moderne de la Ville de Paris, the exhibition tackles an array of subjects, from cultural and political shifts to religion, sexuality, and war. A variety of movements are explored, including the op and kinetic art movements of the 1960s, through to the minimalism of the 70s and 80s as well as contemporary artists who have fingers in both pies such as Maya Rochat.

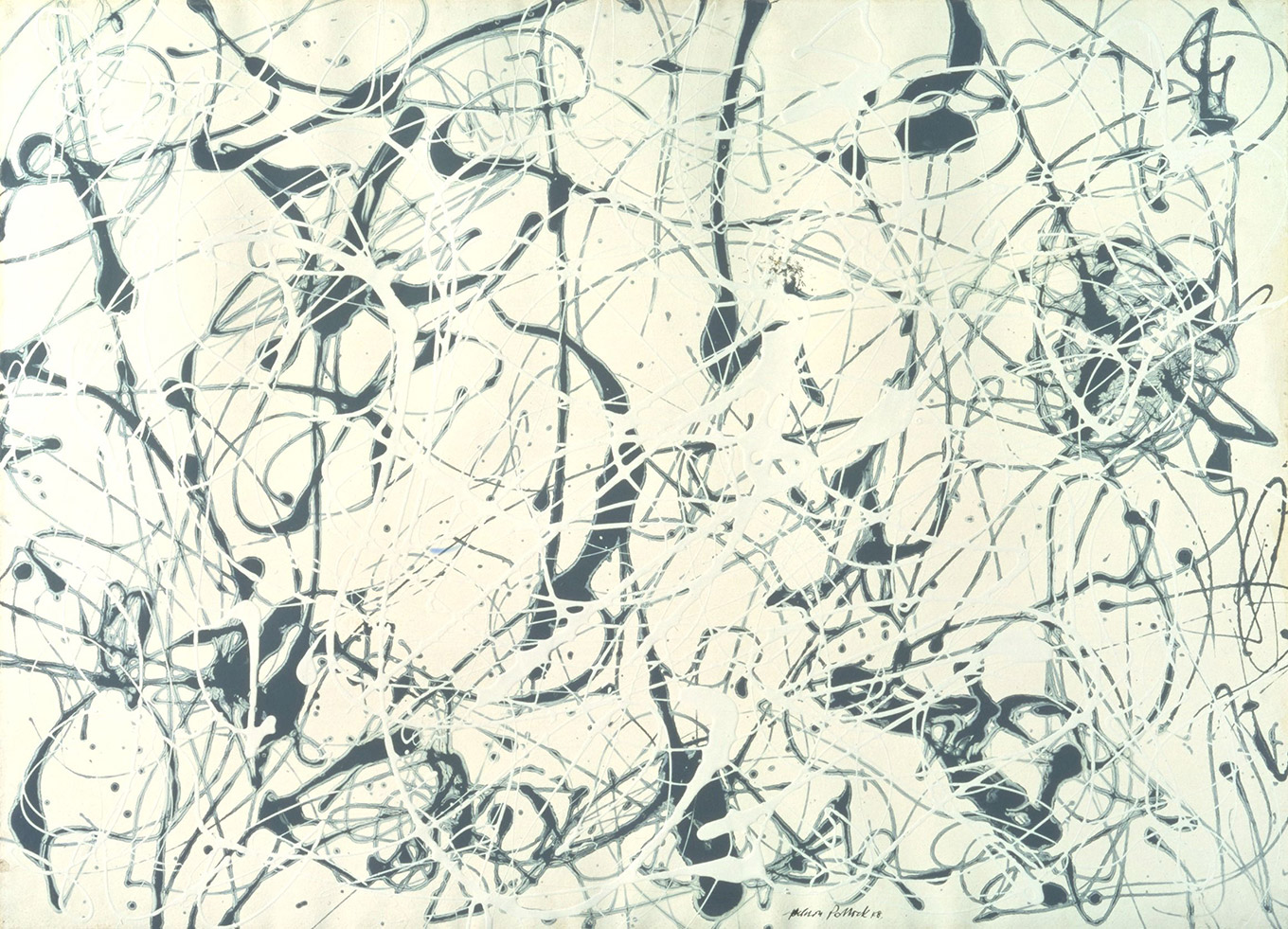

Number 23, 1948, by Jackson Pollock. Tate. © ARS, NY and DACS, London 2018

‘Shape of Light’ also pays homage to a milestone MoMA showcase in 1960 of 300 photographs by 75 international artists, highlighting work whose sole function was to ‘delight or affront the eye.’ A few pieces at Tate Modern appeared in ‘The Sense of Abstraction’, notably the 1959 Unconcerned series by surrealist icon Man Ray – exhibited in London for the first time since their New York outing.

The MoMA exhibition took place at a time when the protagonists of abstract expressionism were beginning to rally an impassioned response to the Technicolor materialism of American culture. Pumped up with the vitality of expressionism, the king of action painting Jackson Pollock produced monumental work dense with physicality: looped, splashed and rhythmic, a web of line, colour and authority. But even Pollock was clearly influenced by earlier photographers, with parallels laid bare in the monochromatic Light Tapestry of Nathan Lerner and the striking luminograms of Otto Steinert created against the austere backdrop of the Second World War.

Elsewhere in the show, the evolution of photography is traced through experimental photographers like Alvin Langdon Coburn, as well as the clinical, metallic constructs of Luisa Lambri and the ambiguous ‘metropolises’ of Antony Cairns. Standing by a wall of 35mm negatives displayed through ‘hacking’ the screens of an outmoded generation of Kindle e-readers, Cairns said of his new series, ‘There’s something in using a material which is completely defunct for purpose; in using things that people don’t want.’

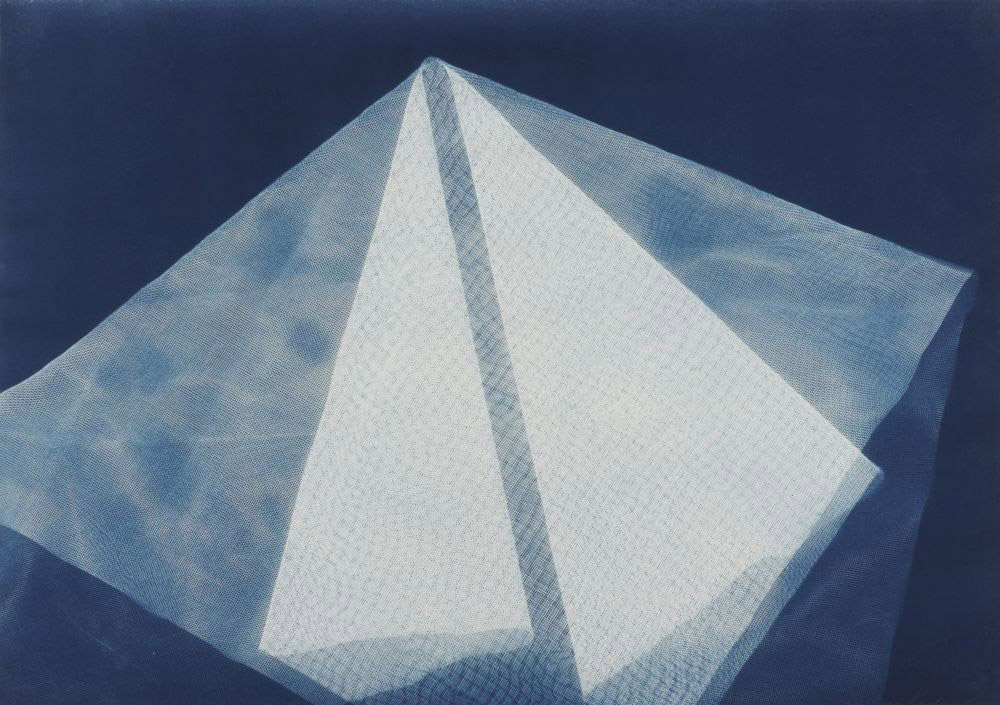

Photogenic Painting, Untitled 74/13, 1974, by Barbara Kasten. Courtesy of the artist, Thomas Dane Gallery and Bortolami Gallery, New York. © Barbara Kasten

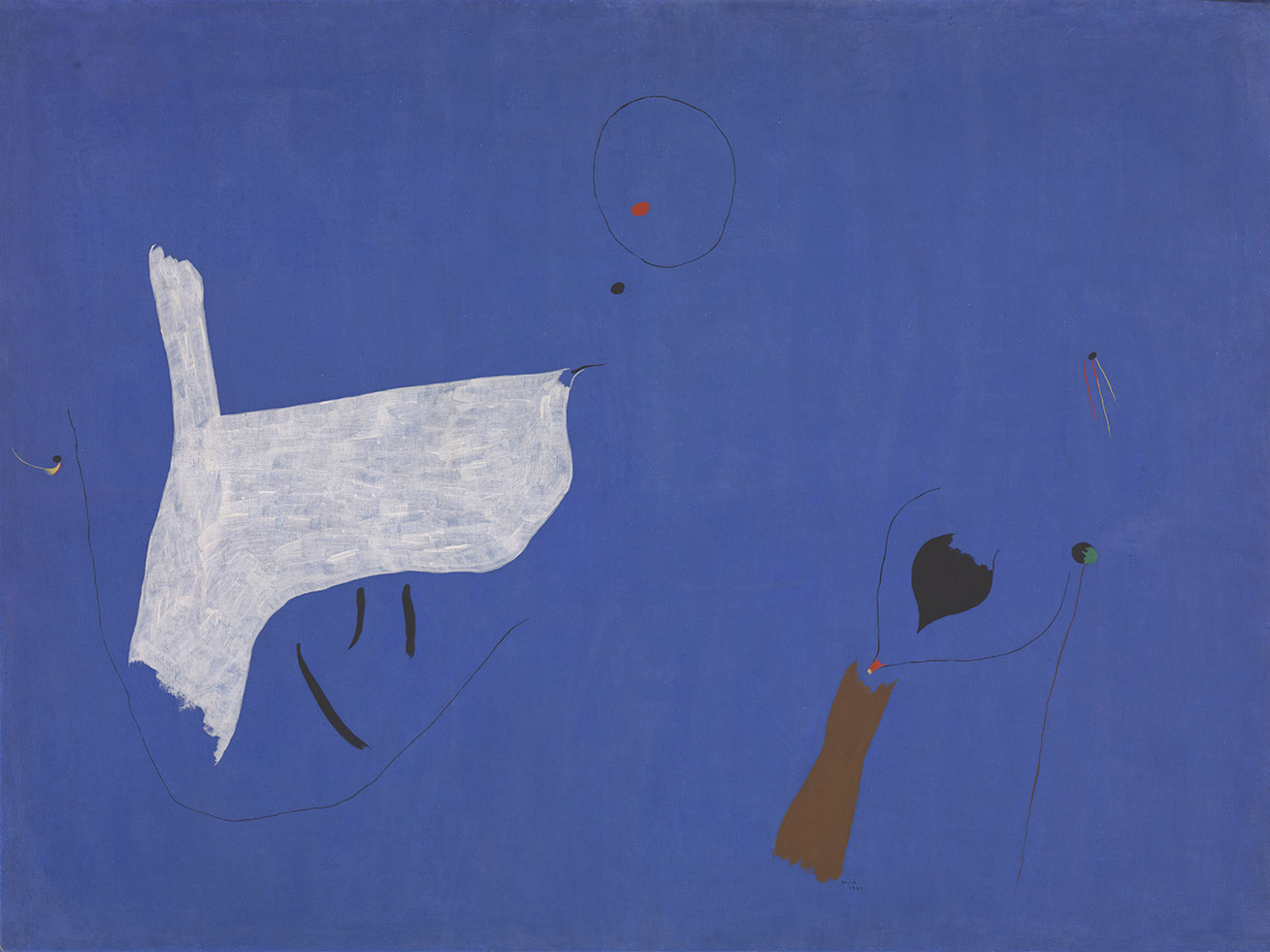

The conflict between capturing versus constructing reality; the dialogue between the literal and the abstract, and most importantly, how these can be blurred are all explored. This exhibition is less about what is said in individual works, but rather the conversations between them, such as the warped anatomy of André Kertész, and the cropped bodies in Imogen Cunningham’s Triangles cohabiting the same space as Joan Miró’s major painting from 1927.

‘Shape of Light’ underlines the relationship and tension between a duet of opposing art forms. This is an exhibition that seeks to bind and define the two disciplines, but most crucially, offers proof of their endurance.

Painting, 1927, by Joan Miró. Tate © Succession Miro/ADAGP, Paris and DACS, London 2018

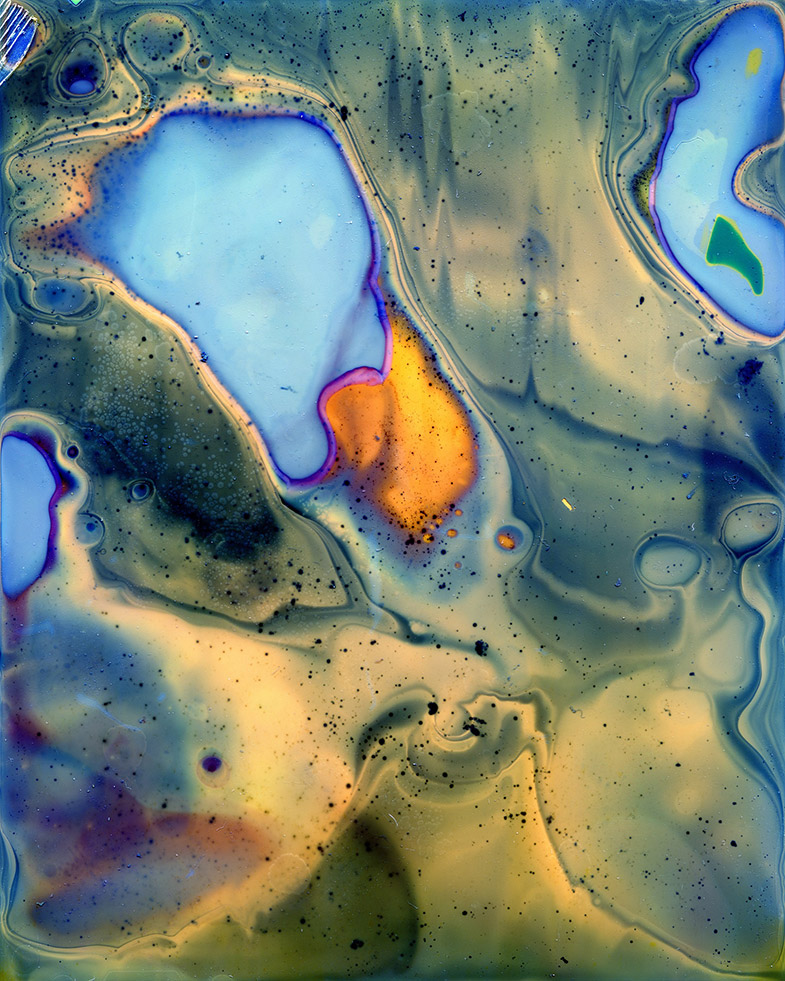

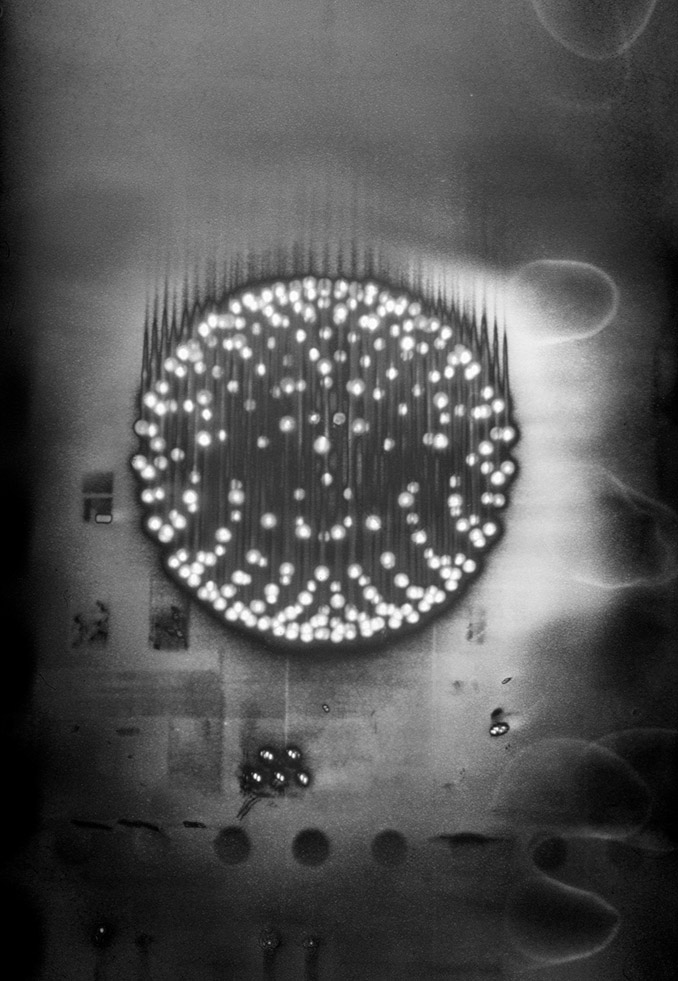

Untitled, 2014, by Daisuke Yokota. Courtesy of the artist and Jean-Kenta Gauthier Gallery. © Daisuke Yokota

Untitled, 1986, by James Welling. Jack Kirkland Collection, Nottingham. © James Welling. Courtesy of the artist and David Zwirner, New York/London/Hong Kong and Maureen Paley, London

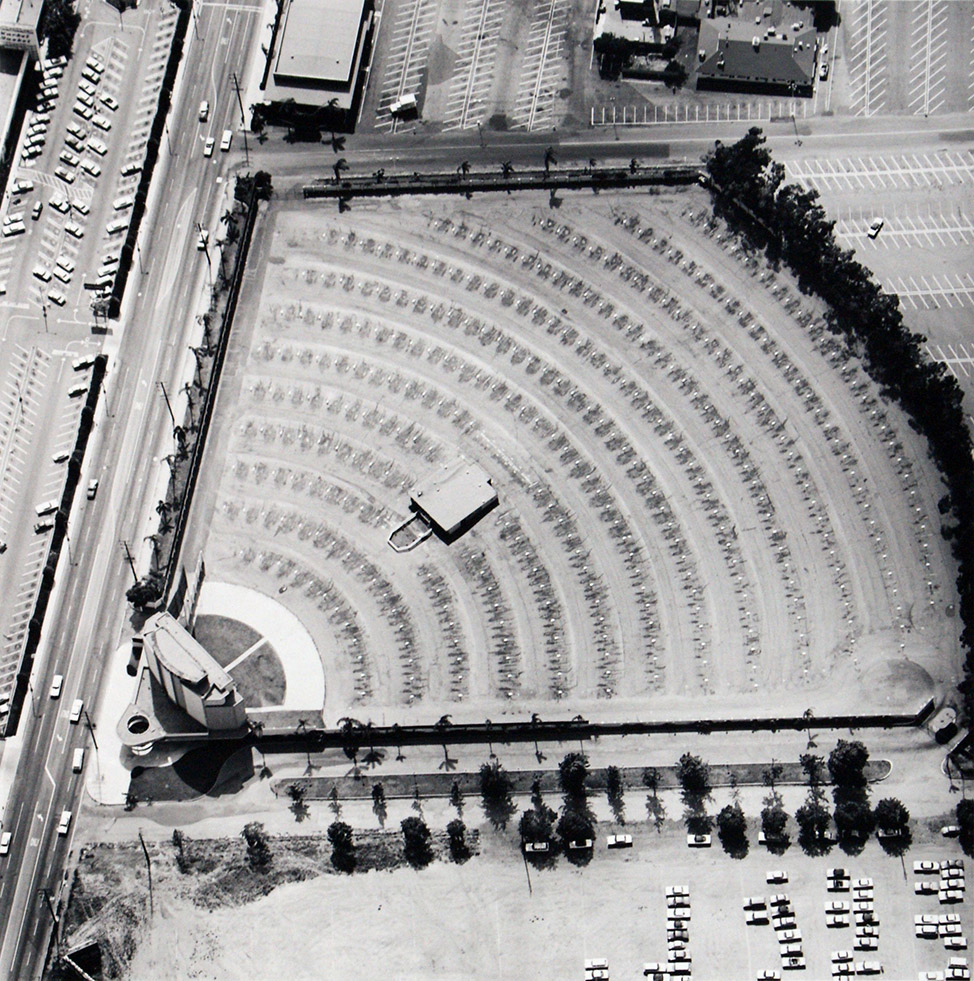

Gilmore Drive-In Theater – 6201 W Third Street, 1967, by Ed Ruscha. Courtesy of the artist and Gagosian Gallery. © Ed Ruscha

LDN5_051, 2017, by Antony Cairns. © Antony Cairns

Vortograph, 1917, by Alvin Langdon Coburn. George Eastman House, Rochester, NY. © The Universal Order

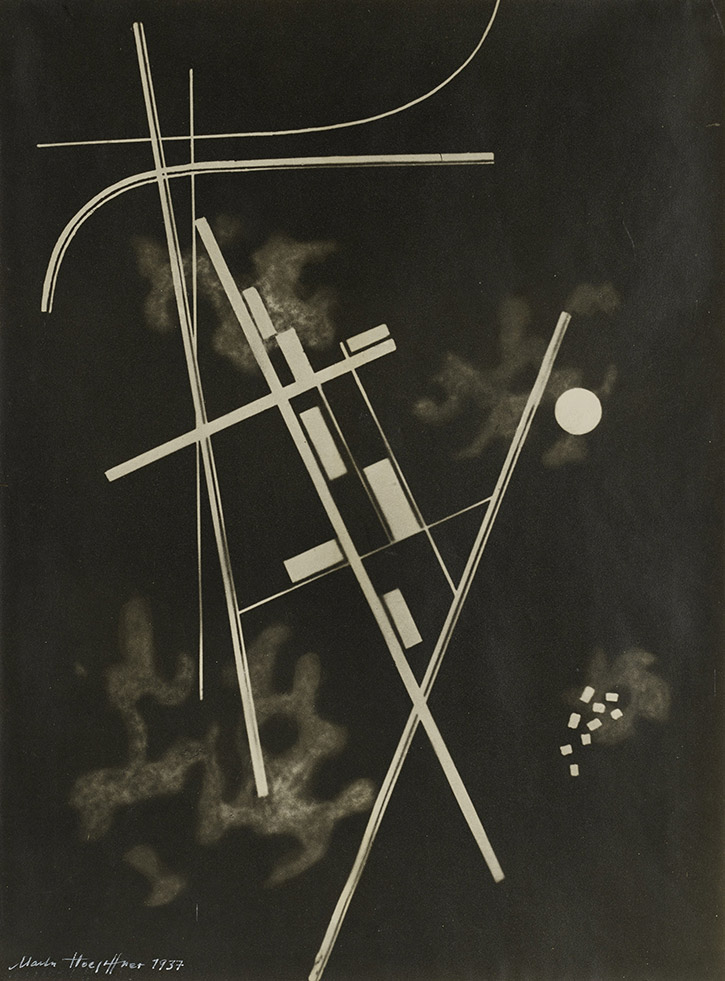

Homage to Kandinsky, 1937, by Marta Hoepffner. Stadtmuseum Hofheim am Taunus. © Estate Marta Hoepffner

Swinging, 1925, by Wassily Kandinsky. Courtesy of Tate

INFORMATION

‘The Shape of Light’ is on view until 14 October. For more information, visit the Tate Modern website

ADDRESS

Tate Modern

Bankside

London SE1 9TG

Wallpaper* Newsletter

Receive our daily digest of inspiration, escapism and design stories from around the world direct to your inbox.

Harriet Lloyd-Smith was the Arts Editor of Wallpaper*, responsible for the art pages across digital and print, including profiles, exhibition reviews, and contemporary art collaborations. She started at Wallpaper* in 2017 and has written for leading contemporary art publications, auction houses and arts charities, and lectured on review writing and art journalism. When she’s not writing about art, she’s making her own.

-

All-In is the Paris-based label making full-force fashion for main character dressing

All-In is the Paris-based label making full-force fashion for main character dressingPart of our monthly Uprising series, Wallpaper* meets Benjamin Barron and Bror August Vestbø of All-In, the LVMH Prize-nominated label which bases its collections on a riotous cast of characters – real and imagined

By Orla Brennan

-

Maserati joins forces with Giorgetti for a turbo-charged relationship

Maserati joins forces with Giorgetti for a turbo-charged relationshipAnnouncing their marriage during Milan Design Week, the brands unveiled a collection, a car and a long term commitment

By Hugo Macdonald

-

Through an innovative new training program, Poltrona Frau aims to safeguard Italian craft

Through an innovative new training program, Poltrona Frau aims to safeguard Italian craftThe heritage furniture manufacturer is training a new generation of leather artisans

By Cristina Kiran Piotti