Shawanda Corbett on breaking the mould of ceramic art

American artist Shawanda Corbett’s performative pottery is shaped by history, music and theories around a ‘complete body’. Her show, ‘To the Fields of Lilac’, runs until 5 March 2022 at Salon 94, New York

If you haven’t heard much about Shawanda Corbett yet, you probably soon will. The Mississippi-born and Oxford, UK-based artist is rapidly remoulding the parameters of ceramic art – its history, cultural gravity and relationship with the human body.

Corbett positions ceramics as an inherently interdisciplinary, cross-cultural medium encompassing film, dance, music, poetry and pottery. These ‘performative objects’ speak across cultures, eras and geographies, from pottery traditions in West Africa and Asia to Greek theatre performances that were recorded on clay vessels. ‘I turned my ceramics practice into a theory: how I respond to spaces, how I respond to music,’ Corbett tells me over the phone. ‘It’s a type of structure that is malleable, that can change depending on the space and the people I’m talking about.’

Corbett’s approach to clay is collaborative; she works with it, as opposed to making it work for her. ‘One of the great things about clay is that it has a memory. In Western places that [teach] ceramics, we’re taught to knock the memory out to make it the way we want it to be. So it’s a power struggle,’ she says. ‘I wanted to do something different. I wanted it to be more about really listening to what the clay wants to do.’

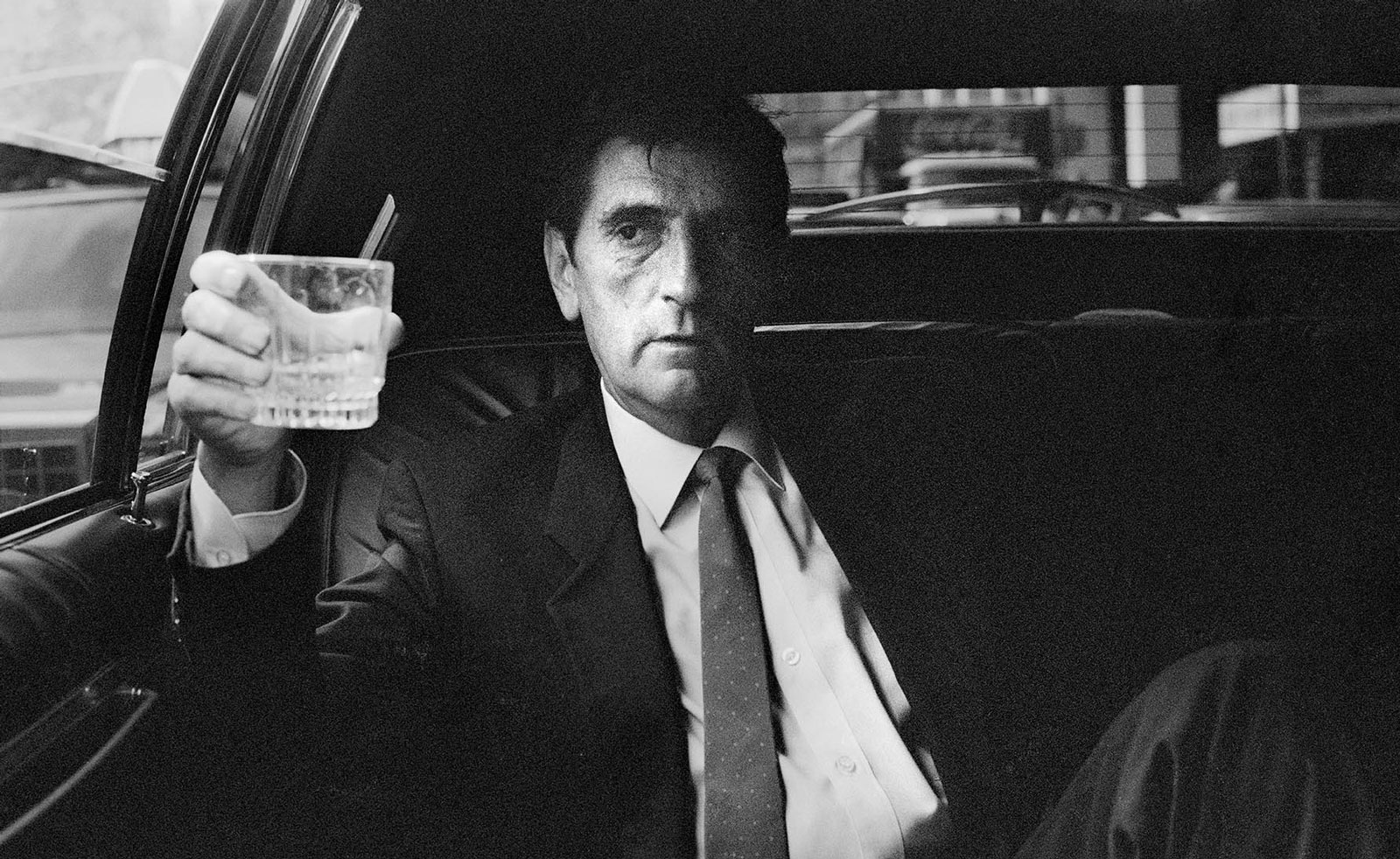

Top: Shawanda Corbett, It was just yesterday, 2021, Chromogenic print. Above: Shawanda Corbett, Do you know where we are, 2021, Glazed stoneware

Corbett refers to herself as a ‘cyborg’ artist. This term may conjure images of tinny 1960s sci-fi movies and metal-plated robot men, but for Corbett (her love of sci-fi aside), it refers to anything mechanical that can enhance human life. ‘It came about when I read Donna Haraway’s Cyborg Manifesto (1985). I wanted to use [the book] but with my perspective: a Black woman, queer, disabled and all these other social identities that I have, whether decided or decided for me,’ says the artist, who was born with one arm and without legs. ‘Terminology around disability or anything like that has such a heavy history to it. And it’s something that I don’t necessarily identify with. I would prefer to be called a cyborg.’

The artist is carrying out a practice-led doctoral degree at the Ruskin School of Art in Oxford. Her research is based on ethics in AI, the relationship between the differently-abled body and the abled body, and the meaning of a ‘complete body’. Her days in the studio are experimental and enveloped by music, including the likes of John Coltrane, Alice Coltrane and Pharoah Sanders. ‘I love the complexity of Jazz’, she says. ‘To an untrained ear, it might sound unorganised or freeform, even though it’s far more complex. It’s organised; to be able to play like that takes a lot of skill. I have a playlist for every body of work. I never repeat a song twice.’ The artist’s affinity with music is deeply rooted in her childhood in Mississippi, where music wasn’t just part of life, but a soundtrack to it. ‘We had music for everything: to get the mood up, to have company over or clean up. I’m used to that, so I wanted it to be part of my practice.’

Installation view of Shawanda Corbett, ‘To the Fields of Lilac’.

Corbett cites her artistic influences with equal enthusiasm, from Ladi Kwali to Theaster Gates, Shōji Hamada to Kawai Kanjirō. But her voice reaches its highest levels of fervour when talking about Magdalene Odundo, whom she first encountered when the Kenyan-born British artist was speaking at the 2012 Alabama Clay Conference. ‘My education in the history of ceramics [was] all white,’ she says. ‘I’d never seen her work before, but when she started speaking about her work it made me feel so much better about how I make things. When I do hand building, it’s West African, that’s naturally what I do. People see West African pottery as primitive, which it absolutely is not.’

RELATED STORY

Corbett describes her throwing technique as an ever-evolving ‘hotch potch’ of approaches. ‘I look at other artists and how they throw and handle clay, because [they’re] so different, and sometimes their way of doing it is so much better than what I’m doing,’ she says. ‘It’s a very physical thing. And in a medical sense, it can cause injuries if you do it the same way too much. Because I do it with one hand, it’s about keeping the muscles evenly working.’

Wallpaper* Newsletter

Receive our daily digest of inspiration, escapism and design stories from around the world direct to your inbox.

Shawanda Corbett, Stop all that slouching, boy, 2021, Glazed stoneware.

In January 2022, Corbett opened her first solo show in the United States. ‘To the Fields of Lilac’ at Salon 94, New York (until 5 March), is part installation, part ‘stereotype-free’ gathering. The exhibition is an ensemble of 16 totemic vessels of different heights, shapes and glazes. Violet hues meet electric blues, some vessels stand up straight, others lean to one side with minds of their own. Each is named with a familiar phrase: Do you see what I see; Stop all that slouching, boy; Just the blind leading the blind; Our freedom is not your absolute freedom (all works 2021). These anthropomorphic objects are based on groups of people, their glossy surfaces etched or scored with traces of the music Corbett was listening to while she worked. The walls are lined with vibrant, abstract paintings, punctuated by large-scale photographs picturing the artist masked in clay slip engraved with gestural lines.

‘I named the show “To the Fields of Lilac” to signal a continuation or a further narrative that thinks about what happens beyond “Wade in the Water”, the spiritual song originally sung by slaves on their quest for freedom, and thinking about how water became a signifier for protection for the enslaved on their road to freedom,’ says the artist, who also has work on show in ‘Body Vessel Clay’ at London's Two Temple Place and will stage a solo exhibition at Tate Britain in May 2022 as part of Art Now (opening 29 May).

Freedom as a point of enquiry – though historically fraught and ever-questionable in a capitalist society – is deeply introspective for Corbett. ‘Freedom is about self-love. It’s always pushing up against what socially you are expected to do, be, or say. It’s how do you receive love from yourself, and that’s the thing we don’t talk about. Underneath a lot of my work, if not all of my work, is freedom as a love story to yourself.’

Shawanda Corbett, We are almost there, 2021, Glazed stoneware

INFORMATION

Shawanda Corbett, ‘To the Fields of Lilac’, until 5 March, Salon 94, New York. salon94.com

Corbett’s show at Tate Britain for Art Now runs from 28 May 2022 - Sun 4 Sept 2022. tate.org.uk

Harriet Lloyd-Smith was the Arts Editor of Wallpaper*, responsible for the art pages across digital and print, including profiles, exhibition reviews, and contemporary art collaborations. She started at Wallpaper* in 2017 and has written for leading contemporary art publications, auction houses and arts charities, and lectured on review writing and art journalism. When she’s not writing about art, she’s making her own.

-

All-In is the Paris-based label making full-force fashion for main character dressing

All-In is the Paris-based label making full-force fashion for main character dressingPart of our monthly Uprising series, Wallpaper* meets Benjamin Barron and Bror August Vestbø of All-In, the LVMH Prize-nominated label which bases its collections on a riotous cast of characters – real and imagined

By Orla Brennan

-

Maserati joins forces with Giorgetti for a turbo-charged relationship

Maserati joins forces with Giorgetti for a turbo-charged relationshipAnnouncing their marriage during Milan Design Week, the brands unveiled a collection, a car and a long term commitment

By Hugo Macdonald

-

Through an innovative new training program, Poltrona Frau aims to safeguard Italian craft

Through an innovative new training program, Poltrona Frau aims to safeguard Italian craftThe heritage furniture manufacturer is training a new generation of leather artisans

By Cristina Kiran Piotti

-

Leonard Baby's paintings reflect on his fundamentalist upbringing, a decade after he left the church

Leonard Baby's paintings reflect on his fundamentalist upbringing, a decade after he left the churchThe American artist considers depression and the suppressed queerness of his childhood in a series of intensely personal paintings, on show at Half Gallery, New York

By Orla Brennan

-

Desert X 2025 review: a new American dream grows in the Coachella Valley

Desert X 2025 review: a new American dream grows in the Coachella ValleyWill Jennings reports from the epic California art festival. Here are the highlights

By Will Jennings

-

This rainbow-coloured flower show was inspired by Luis Barragán's architecture

This rainbow-coloured flower show was inspired by Luis Barragán's architectureModernism shows off its flowery side at the New York Botanical Garden's annual orchid show.

By Tianna Williams

-

‘Psychedelic art palace’ Meow Wolf is coming to New York

‘Psychedelic art palace’ Meow Wolf is coming to New YorkThe ultimate immersive exhibition, which combines art and theatre in its surreal shows, is opening a seventh outpost in The Seaport neighbourhood

By Anna Solomon

-

Wim Wenders’ photographs of moody Americana capture the themes in the director’s iconic films

Wim Wenders’ photographs of moody Americana capture the themes in the director’s iconic films'Driving without a destination is my greatest passion,' says Wenders. whose new exhibition has opened in New York’s Howard Greenberg Gallery

By Osman Can Yerebakan

-

20 years on, ‘The Gates’ makes a digital return to Central Park

20 years on, ‘The Gates’ makes a digital return to Central ParkThe 2005 installation ‘The Gates’ by Christo and Jeanne-Claude marks its 20th anniversary with a digital comeback, relived through the lens of your phone

By Tianna Williams

-

In ‘The Last Showgirl’, nostalgia is a drug like any other

In ‘The Last Showgirl’, nostalgia is a drug like any otherGia Coppola takes us to Las Vegas after the party has ended in new film starring Pamela Anderson, The Last Showgirl

By Billie Walker

-

‘American Photography’: centuries-spanning show reveals timely truths

‘American Photography’: centuries-spanning show reveals timely truthsAt the Rijksmuseum in Amsterdam, Europe’s first major survey of American photography reveals the contradictions and complexities that have long defined this world superpower

By Daisy Woodward