Special argent: a silvered family house holds its own at French sculpture park Domaine du Muy

If residential alchemy were a thing – say, transforming a most banal abode into something altogether remarkable, with bonus points awarded for facades that resemble precious metals – a winning example comes in the shape of a silver house, tucked into the verdant hills of Provence, gently glowing.

At first glance, it’s hard to know whether to think it bombastic, brilliant or just plain weird. There is nothing graceful about the awkward, boxy proportions of the structure itself, a faux-Provençal new-build with a fortress-like feel, but its redemption comes through its hue. Depending on the weather or the time of day, it transitions from sterling to dark grey to dusty blue to olive-tree green. A chameleon house, if you will: a bit funny-looking, but not without charm.

Formally named the Silver House on completion of the renovation this summer, the property is the final touch to Domaine du Muy, a sprawling outdoor sculpture park set across ten hectares of untamed inland terrain near the Massif de l’Esterel mountain range, some 45 minutes north of St-Tropez. ‘We were all slightly terrified that the reflections from the paint might burn us to a crisp when we were out on the terrace,’ says Edward Mitterrand, a Geneva-based art adviser and the artistic director of Domaine du Muy, who asked Paris-based designer and architect India Mahdavi to transform the house. ‘But it turned out more than fine. From a building that was really not elegant or breathtaking or interesting architecturally, India created a different kind of place. Before, it was nothing, whereas now it is something.’

Indeed, what began as a semi-finished and orange-coloured leftover when Edward and his father – the gallerist Jean-Gabriel Mitterrand – took over the property in 2014 is now an attraction in its own right; an intriguing, metallic complement to the 42 artworks that lurk in the park beyond.

The living space, with ‘Sunshine’ table, specially designed for the space, and ‘Cap Martin’ chairs, both by India Mahdavi. On the ceiling is 'Rescinded Platform', by Liam Gillick, 2015.

‘I’m the first to acknowledge that this will never be great architecture,’ says Mahdavi. She was tasked with making the most of the house – it couldn’t be demolished for ‘boring, administrative reasons’ – while creating a family holiday home-meets-flexible gallery space for the Mitterrands. ‘As we were sort of stuck with it, we had to make a strong statement and that really ended up being: let’s erase the house altogether, by painting it silver so it reflects the sky and the landscape,’ says the designer. No stranger to working in this region of France, she has outfitted the Monte-Carlo Beach hotel in Monaco, Maja Hoffman’s Hôtel du Cloître in Arles, and several private homes in Cap Ferret.

The striking paint job took its cue from a sculpture visible from the home’s expansive terrace. Past two small, artificial lakes (currently host to Yayoi Kusama’s Narcissus Garden, 1966-2011, which comprises 1,600 mirrored steel balls bobbing on the surface), the not-so-subtle glint of a 7m stack of oversized stainless steel buckets (A Giant Leap of Faith, 2006) by Subodh Gupta caught Mahdavi’s eye.

Of course, the silver plating is just part of the story – the interiors reveal a more understated side to the house’s reinvention. The upstairs, which has three of the four bedrooms, is rather light-touch on the design front, Mahdavi notes, while the ground floor got the full treatment. There, geometric black and white tiles – designed by Mahdavi for Bisazza – create a bold, graphic symmetry underfoot, while arched cut-out doorways separate the foyer, the dining area and the main living space, adding a bit of the softness of the south of France.

A mix of the Mitterrands’ own furniture and several of Mahdavi’s designs – her signature ‘Jelly Pea’ sofas and a bespoke glass and rattan dining table called ‘Sunshine’ among them – perfectly capture the kind of stylish haphazardness that seems to permeate the region. A souped-up Ikea kitchen sits to the side of the main entrance, while vaulted, steel-framed double doors open onto the terrace. Mahdavi expanded and elongated this outdoor area to widen the silhouette of the house, supplementing its square footage with plenty of external living space.

‘At first, the house was sort of a vertical horror story on a hill, so we had to find a way to rewrite it into the landscape and take it off its pedestal,’ says Mahdavi. Removing the earth in front of the building and erasing the hill also made room for a spacious gallery, which now sits below the house and opens gracefully onto a sloping lawn. Notably, there is no internal staircase linking the gallery and the living spaces – a conscious choice to separate the public from the private.

‘It was about giving the house horizontal roots, if you will, and making it look as if it had been sitting there for a long time,’ says Mahdavi. It’s a stretch to say the house appears organic in the landscape, but there are romantic details – the enamelled-tile curves of the moucharaby lining the balcony, the undulating terracotta roof – that make it feel very right in Provence.

The building’s presence is also tempered, or contextualized, by the handiwork of lauded landscape architect Louis Benech. Perhaps best known for his restoration of the Jardin des Tuileries in Paris and his work on the Water Theatre grove at Versailles, his clients range from interior designer Jacques Grange to fashion house Hermès.

At Domaine du Muy, Benech has allowed indigenous lupins, heather, lavender, cork oaks and strawberry trees to make their way close to the house, echoing the wilder versions that can be found in the park beyond. To one side of the building, he has created a formal lawn area where mulberries, leadwort, orange and olive trees form a more manicured scenario. A border of cypresses and plane trees will grow tall with time, providing privacy from the driveway and concealing the neighbouring homes.

Benech refers to du Muy as a ‘non-project’ that was more about reparations and erasing the obvious human interventions of the past. ‘There are gardens where I am inventing a story and this was not one of them,’ he says. ‘The concept here was just to be modest or non-present, in a story which is about the art. I hope that in about two or three years no one will think that a human being went through this place. It’s about speeding up nature, and what would happen in ten years, we help it along a little quicker.’

Together, the house and the gardens offer a refined, colourful and comfortable place that can easily serve as both a hideaway and a showcase – a double intention that extends beyond the home and its immediate grounds to Domaine du Muy as a whole. ‘The ambition here is two-fold. There is the personal intention to have a place where we are happy to stay as a family, with friends, artists and clients dropping by,’ says Edward. ‘And there is the professional one: to show great art and create a vitrine that showcases our expertise when it comes to monumental sculpture – from transport and installation to curation and exhibition – which, to date, I think we have undersold.’

'RockStone 198', 2015

That expertise originates with Jean-Gabriel, the founder of Domaine du Muy and the well-regarded Galerie Mitterrand in Paris, which specialises in post-war sculpture. Since opening in the Marais in 1988 (it was then known as JGM to downplay the family name, as Jean-Gabriel’s late uncle, François Mitterrand, was president of France between 1981 and 1995) the gallery has staged countless shows of monumental works around the globe, from Rio to Taipei.

Domaine du Muy brings the Mitterrands’ know-how closer to home, and situates them on the collector-heavy Côte d’Azur art circuit. Father and son have spent the past two years pouring all their energy into this expansive outdoor affair, where artworks by late greats (Sol LeWitt), contemporary superstars (Carsten Höller, Dan Graham, Carlos Cruz-Diez) and young guns (Claudia Comte, Dan Colen) intermingle, amid unruly undergrowth and towering pines.

‘Sophisticated works, architecture and wild nature together – in conversation and in opposition. That is the simple purpose of this place,’ says Jean-Gabriel, who dreamed of creating a park of his own since he visited the Gori Collection at the Villa Celle in Tuscany when it opened in the early 1980s, showcasing a pioneering selection of site-specific works. ‘Le Muy is a wild place, but we have come here with an intellectual idea, and it may not appeal to everyone, but the intention has never been to please the most amount of people.’

Indeed, it is difficult to imagine buses dumping tourists from far-flung nations out front and, for the moment, Domaine du Muy remains more private than public. The park accepts a limited number of visitors by appointment on Thursday mornings during the season, which runs from July to October.

Come winter, the Mitterrands hope to start a residency programme, inviting an artist to stay in the grounds and create an in-situ work for the season ahead. To live in the Silver House, to bask in the garden’s winter sun, to meander among spectacular sculptures old and new: not a bad gig.

As originally featured in the November 2016 issue of Wallpaper* (W*212)

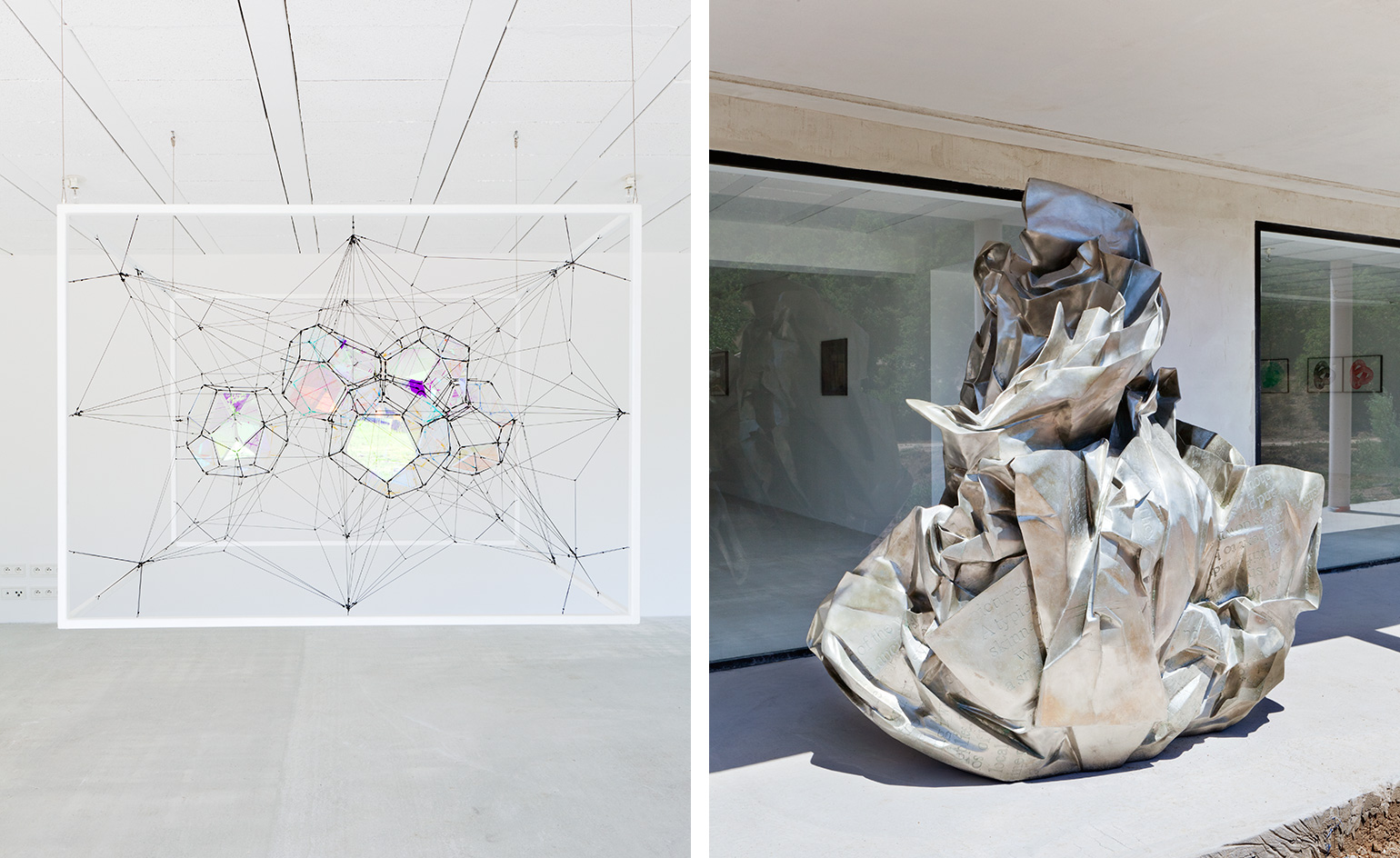

Left, 3C 411, by Tomás Saraceno, 2014. Right, China Daily – Top 10 Profiles of the Urban Male, 2007

Left, India Mahdavi embellished an Ikea kitchen and used her ‘In The Sky 10’ tiles, designed for Bisazza. Right, the new-build house was painted silver to help it become part of the surroundings

Left, Chromosaturation pour une Alée Publique, by Carlos Cruz-Diez (1965-2012). Right, the exhibition space, with chairs by Franz West. On the back wall is Arm, by Peter Kogler, 2016.

INFORMATION

Domaine du Muy is open by appointment only. For more information, visit the website

ADDRESS

Domaine du Muy

Le Muy

Var

Wallpaper* Newsletter

Receive our daily digest of inspiration, escapism and design stories from around the world direct to your inbox.

-

Put these emerging artists on your radar

Put these emerging artists on your radarThis crop of six new talents is poised to shake up the art world. Get to know them now

By Tianna Williams

-

Dining at Pyrá feels like a Mediterranean kiss on both cheeks

Dining at Pyrá feels like a Mediterranean kiss on both cheeksDesigned by House of Dré, this Lonsdale Road addition dishes up an enticing fusion of Greek and Spanish cooking

By Sofia de la Cruz

-

Creased, crumpled: S/S 2025 menswear is about clothes that have ‘lived a life’

Creased, crumpled: S/S 2025 menswear is about clothes that have ‘lived a life’The S/S 2025 menswear collections see designers embrace the creased and the crumpled, conjuring a mood of laidback languor that ran through the season – captured here by photographer Steve Harnacke and stylist Nicola Neri for Wallpaper*

By Jack Moss

-

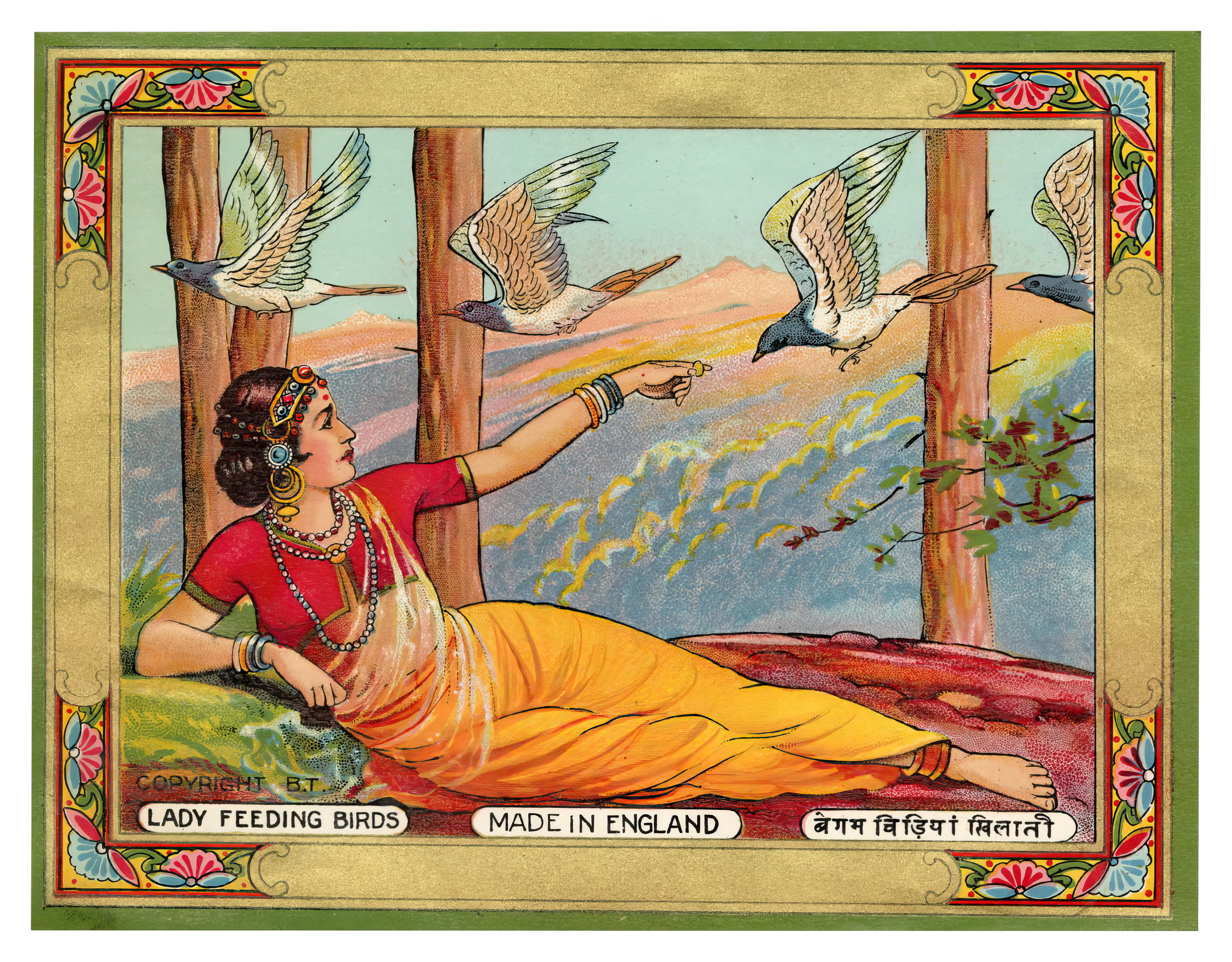

The art of the textile label: how British mill-made cloth sold itself to Indian buyers

The art of the textile label: how British mill-made cloth sold itself to Indian buyersAn exhibition of Indo-British textile labels at the Museum of Art & Photography (MAP) in Bengaluru is a journey through colonial desire and the design of mass persuasion

By Aastha D

-

Inside India’s contemporary art scene

Inside India’s contemporary art sceneEmerging and established artists are bringing the spotlight to India, where Aastha D attended the recent India Art Fair

By Aastha D

-

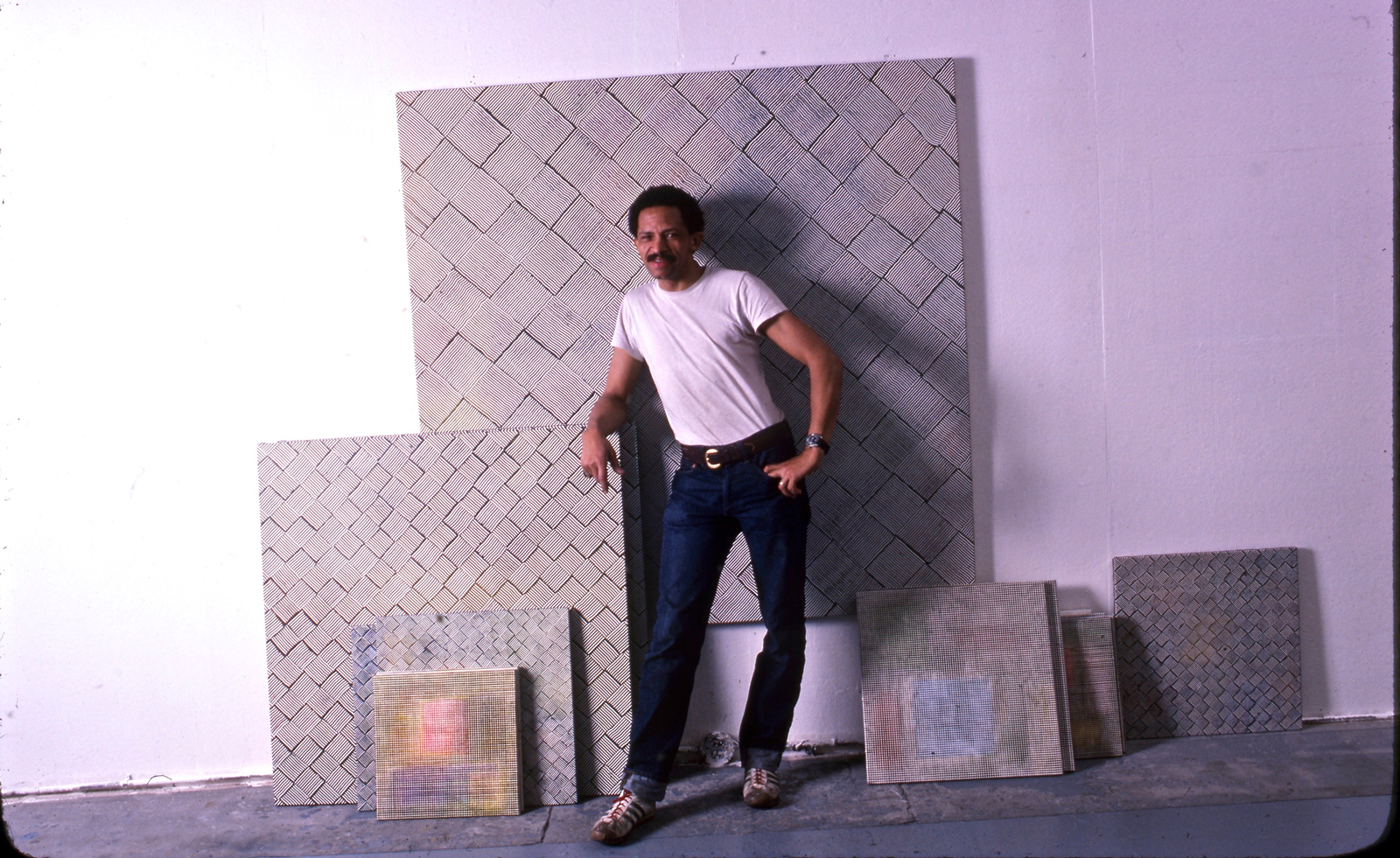

Inside Jack Whitten’s contribution to American contemporary art

Inside Jack Whitten’s contribution to American contemporary artAs Jack Whitten exhibition ‘Speedchaser’ opens at Hauser & Wirth, London, and before a major retrospective at MoMA opens next year, we explore the American artist's impact

By Finn Blythe

-

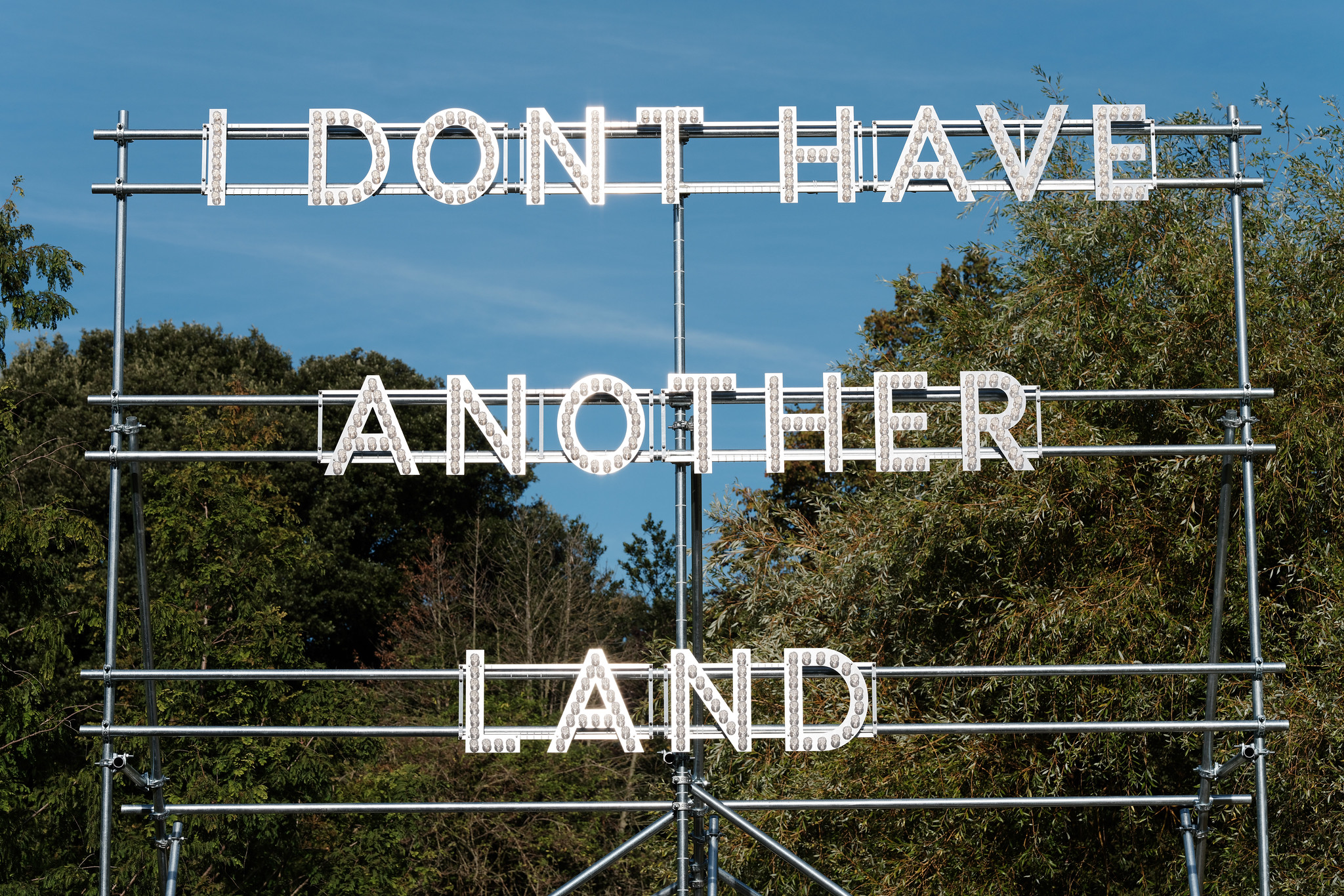

Frieze Sculpture takes over Regent’s Park

Frieze Sculpture takes over Regent’s ParkTwenty-two international artists turn the English gardens into a dream-like landscape and remind us of our inextricable connection to the natural world

By Smilian Cibic

-

Harlem-born artist Tschabalala Self’s colourful ode to the landscape of her childhood

Harlem-born artist Tschabalala Self’s colourful ode to the landscape of her childhoodTschabalala Self’s new show at Finland's Espoo Museum of Modern Art evokes memories of her upbringing, in vibrant multi-dimensional vignettes

By Millen Brown-Ewens

-

Wanås Konst sculpture park merges art and nature in Sweden

Wanås Konst sculpture park merges art and nature in SwedenWanås Konst’s latest exhibition, 'The Ocean in the Forest', unites land and sea with watery-inspired art in the park’s woodland setting

By Alice Godwin

-

Pino Pascali’s brief and brilliant life celebrated at Fondazione Prada

Pino Pascali’s brief and brilliant life celebrated at Fondazione PradaMilan’s Fondazione Prada honours Italian artist Pino Pascali, dedicating four of its expansive main show spaces to an exhibition of his work

By Kasia Maciejowska

-

John Cage’s ‘now moments’ inspire Lismore Castle Arts’ group show

John Cage’s ‘now moments’ inspire Lismore Castle Arts’ group showLismore Castle Arts’ ‘Each now, is the time, the space’ takes its title from John Cage, and sees four artists embrace the moment through sculpture and found objects

By Amah-Rose Abrams