All American: Stuart Davis’ brand of modernism takes over New York

Abstract yet concrete. Geometric, but figurative. Stuart Davis was a painter who lived for the contradiction, and yet somehow found resolution in his mesmerising paintings, heralding him as an American original, a fine art force fueled by aesthetics and politics equally.

This week, the Whitney Museum of American Art opens a retrospective, in conjunction with the National Gallery of Art, titled ‘Stuart Davis: In Full Swing,’ that traces near 100 works from his early paintings in the 1920s to his depictions of consumer products until the 1960s, when his fusion of dynamism and vivid colours led him to neither embrace abstraction fully nor to abandon figuration completely.

It’s fitting for the Whitney to reconsider this artist, whom not only was a personal friend and favourite of Gertrude Vanderbilt Whitney, but was also a founding member of the Whitney Studio Club and had his first solo exhibition at the institution in 1926. While he was a true-blood American, his sense of identity was not the idealised pastoral, but rather formed by the New York streets and Newark's hot jazz joints—modernity was pluralistic, a notion not shared by others in Davis’ time.

As this retrospective shows, though Davis was in all the right places at all the right times, even rubbing elbows with those who went on to be anointed as ‘establishment,’ the most precious dialogue he created was with himself. Take Paris, for example, to which Davis arrived in 1928. While Davis’ works from that period may look like cubist or surrealist extensions, they were anything but.

Throughout the exhibition, the show’s curators, Barbara Haskell and Harry Cooper, consistently remind viewers of this phenomenon: old and new works are placed side-by-side to demonstrate how motifs or ideas from the 1920s remained powerful to Davis throughout his exuberant jazz period, and the 1950s and ’60s. Underscoring Davis’ practice was the notion that art played a social role, and thus throughout his oeuvre, he maintained a formal principle of using only ‘shallow space,’ so the canvas didn’t deceive or seduce unjustly.

While he abstracted his famous eggbeaters (a recurring object in his still lifes), and animated words and jazz notes into geometric symbols, in many ways, Davis saw the future as bright, full-speed and inherently contained.

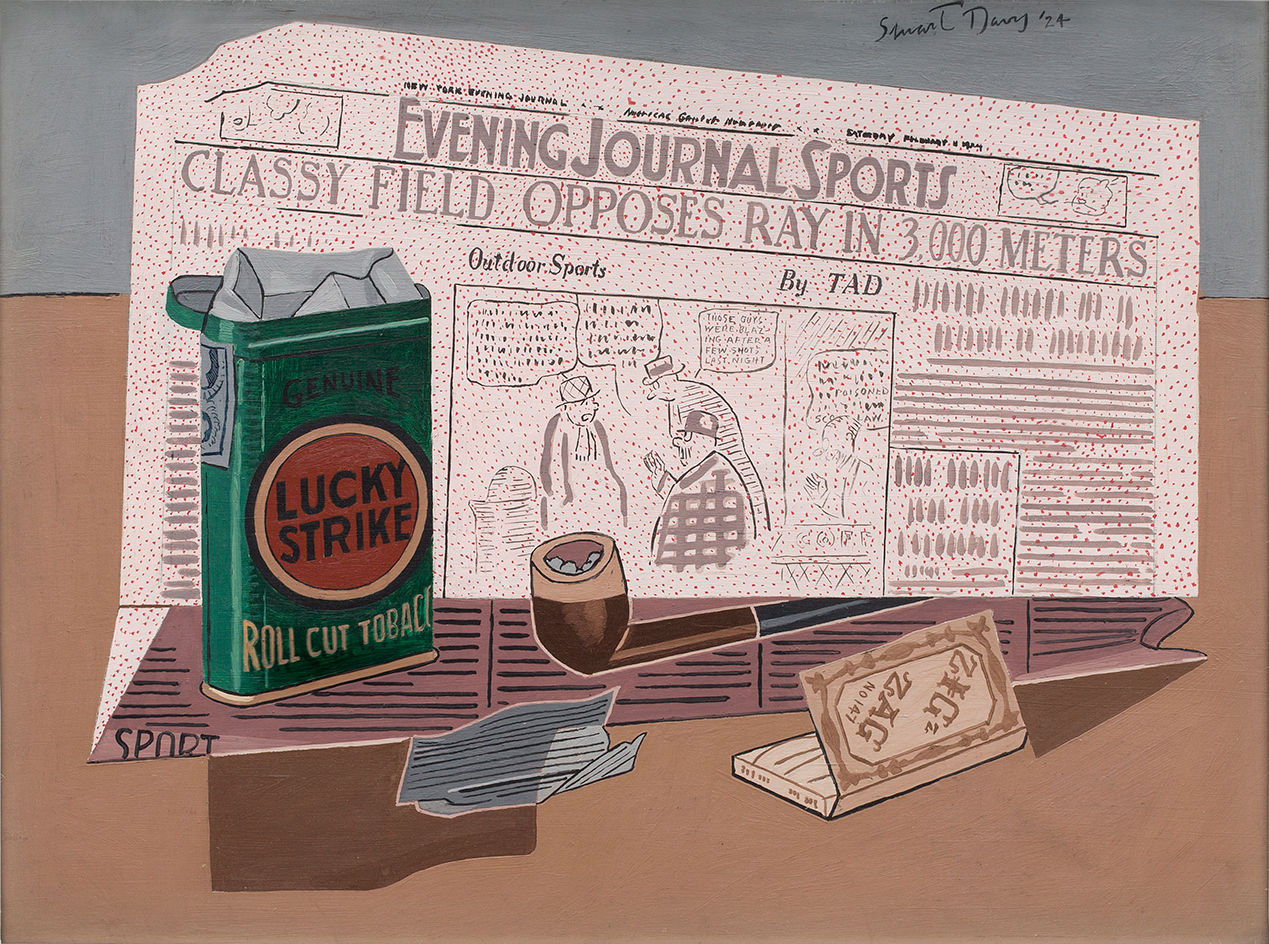

The retrospective, staged together with the National Gallery of Art, traces near 100 works from Davis' early paintings in the 1920s to his depictions of consumer products from the 1960s. Pictured: Lucky Strike, 1924

Not only was Davis a personal friend and favourite of Gertrude Vanderbilt Whitney, he was also a founding member of the Whitney Studio Club and had his first solo exhibition at the institution in 1926. Pictured: Salt Shaker, 1931

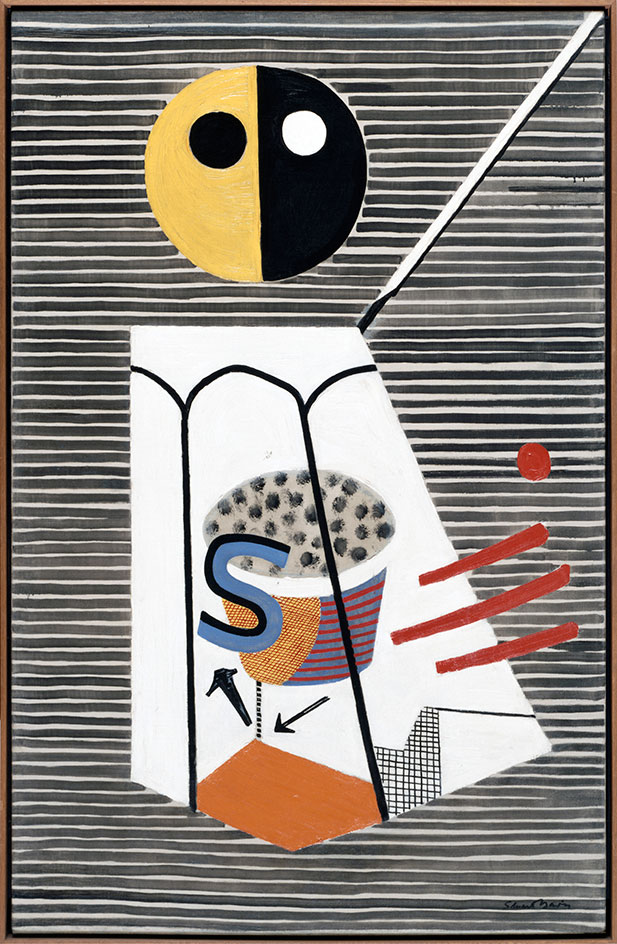

Throughout the exhibition, the show’s curators, Barbara Haskell and Harry Cooper, consistently remind viewers of Davis' individuality. Old and new works are placed side-by-side to demonstrate how motifs or ideas from the 1920s remained powerful to Davis over the years. Pictured: Egg Beater No. 2, 1928

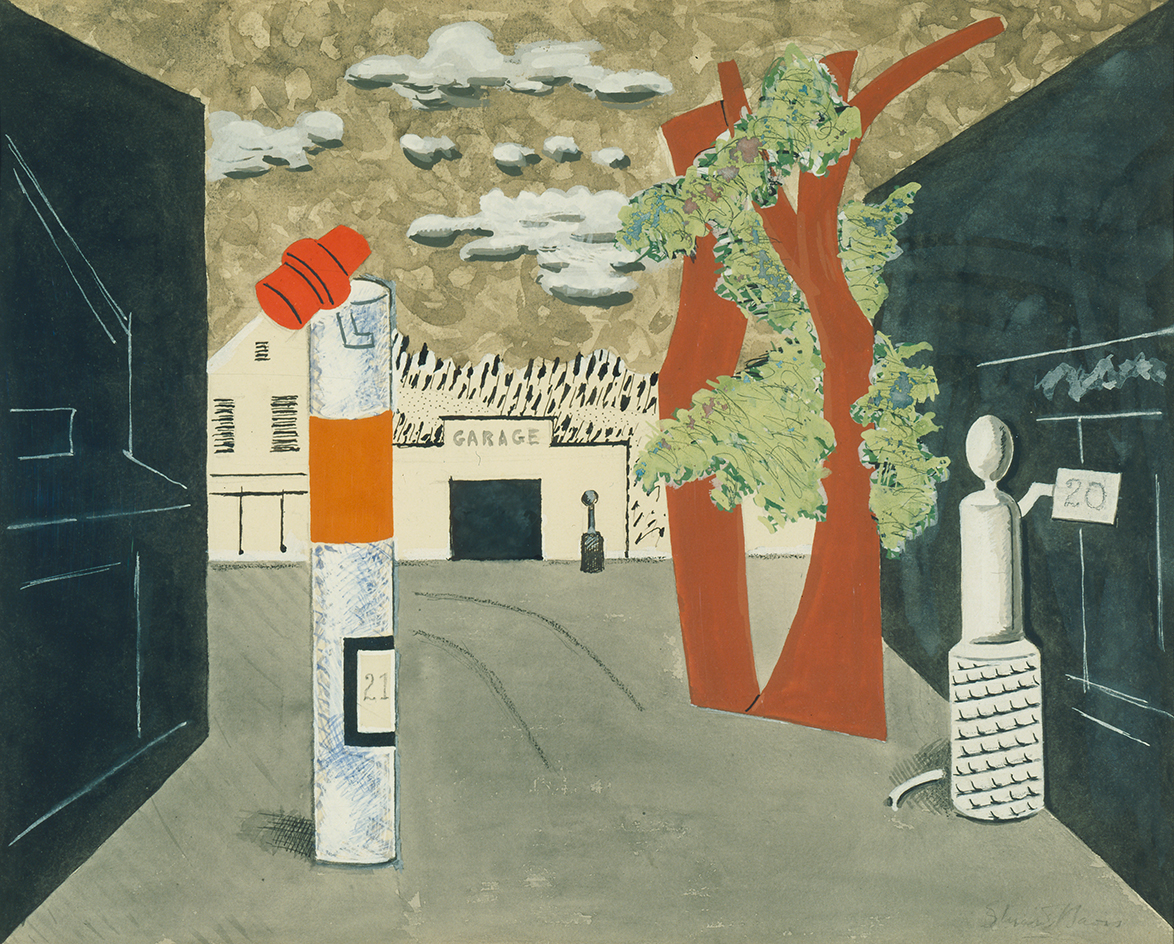

While he was a true-blood American, Davis' sense of identity was not the idealised pastoral, but rather formed by the New York streets and Newark's hot jazz joints. Pictured: Town Square, 1929

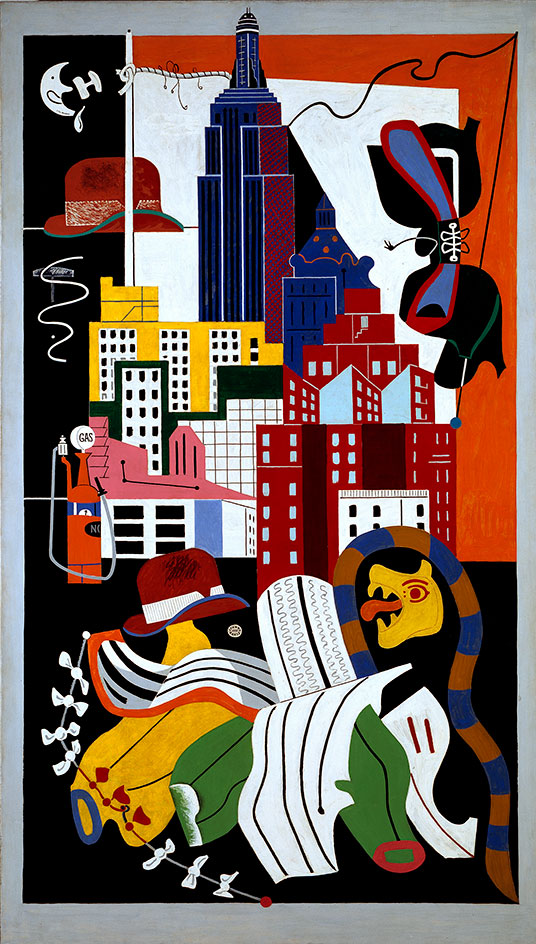

His fusion of dynamism and vivid colours led him to neither embrace abstraction fully nor to abandon figuration completely. Pictured: New York Mural, 1932

Throughout his oeuvre, he maintained a formal principle of using only ‘shallow space,’ so the canvas didn’t deceive or seduce unjustly. Pictured: American Painting, 1932/1942–54

INFORMATION

'Stuart Davis: In Full Swing' opens on 11 June and runs until 25 September. For more details, please visit the museum's website

All images courtesy of the Stuart Davis Estate and the Whitney Museum

ADDRESS

Whitney Museum of American Art

99 Gansevoort Street

New York, New York

Receive our daily digest of inspiration, escapism and design stories from around the world direct to your inbox.

Julie Baumgardner is an arts and culture writer, editor and journalist who's spent nearly 15 years covering all aspects of art, design, culture and travel. Julie's work has appeared in publications including Bloomberg, Cultured, Financial Times, New York magazine, The New York Times, Wall Street Journal, as well as Wallpaper*. She has also been interviewed for The Atlanta Journal-Constitution, Miami Herald, Observer, Vox, USA Today, as well as worked on publications with Rizzoli press and spoken at art fairs and conferences in the US, Middle East and Asia. Find her @juliewithab or juliebaumgardnerwriter.com

-

A tale of two Audis: the A5 saloon goes up against the A6 Avant e-tron

A tale of two Audis: the A5 saloon goes up against the A6 Avant e-tronIs the sun setting on Audi’s ICE era, or does the company’s e-tron technology still need to improve?

-

Inside Christian de Portzamparc’s showstopping House of Dior Beijing: ‘sculptural, structural, alive’

Inside Christian de Portzamparc’s showstopping House of Dior Beijing: ‘sculptural, structural, alive’Daven Wu travels to Beijing to discover Dior’s dramatic new store, a vast temple to fashion that translates haute couture into architectural form

-

A music player for the mindful, Sleevenote shuns streaming in favour of focused listening

A music player for the mindful, Sleevenote shuns streaming in favour of focused listeningDevised by musician Tom Vek, Sleevenote is a new music player that places artist intent and the lost art of record collecting at the forefront of the experience

-

Nadia Lee Cohen distils a distant American memory into an unflinching new photo book

Nadia Lee Cohen distils a distant American memory into an unflinching new photo book‘Holy Ohio’ documents the British photographer and filmmaker’s personal journey as she reconnects with distant family and her earliest American memories

-

Out of office: The Wallpaper* editors’ picks of the week

Out of office: The Wallpaper* editors’ picks of the weekIt’s been a week of escapism: daydreams of Ghana sparked by lively local projects, glimpses of Tokyo on nostalgic film rolls, and a charming foray into the heart of Christmas as the festive season kicks off in earnest

-

This Gustav Klimt painting just became the second most expensive artwork ever sold – it has an incredible backstory

This Gustav Klimt painting just became the second most expensive artwork ever sold – it has an incredible backstorySold by Sotheby’s for a staggering $236.4 million, ‘Portrait of Elisabeth Lederer’ survived Nazi looting and became the key to its subject’s survival

-

Meet Eva Helene Pade, the emerging artist redefining figurative painting

Meet Eva Helene Pade, the emerging artist redefining figurative paintingPade’s dreamlike figures in a crowd are currently on show at Thaddaeus Ropac London; she tells us about her need ‘to capture movements especially’

-

Ed Ruscha’s foray into chocolate is sweet, smart and very American

Ed Ruscha’s foray into chocolate is sweet, smart and very AmericanArt and chocolate combine deliciously in ‘Made in California’, a project from the artist with andSons Chocolatiers

-

Maggi Hambling at 80: what next?

Maggi Hambling at 80: what next?To mark a significant year, artist Maggi Hambling is unveiling both a joint London exhibition with friend Sarah Lucas and a new Rizzoli monograph. We visit her in the studio

-

Out of office: The Wallpaper* editors’ picks of the week

Out of office: The Wallpaper* editors’ picks of the weekThis week, the Wallpaper* editors curated a diverse mix of experiences, from meeting diamond entrepreneurs and exploring perfume exhibitions to indulging in the the spectacle of a Middle Eastern Christmas

-

Artist Shaqúelle Whyte is a master of storytelling at Pippy Houldsworth Gallery

Artist Shaqúelle Whyte is a master of storytelling at Pippy Houldsworth GalleryIn his London exhibition ‘Winter Remembers April’, rising artist Whyte offers a glimpse into his interior world