Tenant of Culture: the artist turning fast fashion into radical hybrid sculpture

Ahead of a major new installation at London’s Camden Art Centre, we speak to Tenant of Culture, whose art-meets-fashion practice dissects the darker sides of our material world

Deconstructed, reconstructed, bleached, re-dyed, hung, wrung out, stacked; Tenant of Culture – the moniker of Dutch artist Hendrickje Schimmel – has a way of handling material.

Known for creating works from used (and sometimes nearly new) garments, Schimmel – who won the 2020 Camden Art Centre Emerging Artist Prize with Frieze – creates cross-bred art-meets-couture sculptures that are at once monstrous and sumptuous. The artist’s work illustrates an industry of extremes and dissects the psychology of break-neck fast fashion and a material world of rapid obsolescence.

On 8 July, Tenant of Culture will unveil ‘Soft Acid’ at Camden Art Centre. The artist’s largest installation to date, it draws directly on the history of the gallery, and stitches together complex stories of gendered domesticity and the hierarchies of supply and demand.

Installation view of Tenant of Culture, ’Soft Acid’ at Camden Art Centre

Installation view of Tenant of Culture, 'Soft Acid' at Camden Art Centre

Wallpaper*: Your installation at London’s Camden Art Centre began in the gallery archives. What did you uncover during research, and how did this inform the work?

Tenant of Culture: I spent some time in the Camden Art Centre archive, initially to look for documentation of workshops held there during the 1960s and 1970s. Instead, I happened upon a leaflet of an exhibition called ‘The Londoners, A Visual Survey of London Working Life from 1866 to 1966’, held in 1966. One of the professions it mentioned was the laundry industry, which I had never heard of. It stated: ‘When the soap tax, enforced until 1852, was finally removed, there was a swing in fashion towards pale-coloured clothes, light muslins and chintz furniture covers. This was echoed by a sudden expansion in [the] laundry industry.’ I decided to focus my research for this exhibition on the history of laundry and its importance in the mass production of textiles and garments, historically as well as [in] contemporary [times].

Tenant of Culture, Cutting Stock (series), 2021

When the laundry industry first emerged, it employed almost solely women, even though the work was extremely tough. Laundry is often associated with domesticity and remains one of the more gendered tasks. It is not something I ever connected with heavy industry, which is probably why there is a distinct lack of research into the subject, in comparison to railways and steel mills for example.

I found a book on the subject by Dr Arwen Mohun called: Steam Laundries, Gender, Technology and Work in the United States and Britain 1880 to 1940. This book traces the social and material conditions that made the commercial laundries so omnipresent, such as urbanisation and changing hygiene standards. In a contemporary context, looking at methods that are used now to mass-produce garments, I mainly focused on processes such as acid and enzyme wash used for the artificial ageing of denim, and finishing processes such as waterproofing and sweat-proofing performance wear. Processes that use enormous amounts of water, which is often released back into the environment, lined with microfibres and traces of chemical dyes.

W*: What can we expect from ‘Soft Acid’?

ToC: The title, ‘Soft Acid’, is a direct reference to the processes mentioned above. Acid is often used to soften a garment before it is distributed, making it more comfortable to wear. The works in the exhibition are all made from second-hand garments, textiles and accessories, that are re-dyed, deconstructed and re-assembled into wearable or non-wearable pieces. I’ve worked a lot with colourful garments this time, and with garments that have gone through some of the processes I mention in [response to] the first question. All of them are suspended from stainless steel construction that references the environment of the commercial laundry and dye factories as well as high-end shop displays.

Wallpaper* Newsletter

Receive our daily digest of inspiration, escapism and design stories from around the world direct to your inbox.

Tenant of Culture, I FORGOT TO TELL YOU I’VE CHANGED, installation view at Fries Museum, Leeuwarden, Netherlands, 2020.

W*: Your sculptures incorporate discarded garments and accessories. Where do you normally source these materials from?

ToC: I source my materials mainly from secondary market places, such as eBay, charity shops, yard sales, or sometimes wholesale vintage. The garments and accessories I use are not necessarily discarded, they are just expelled from the realm of newness. Rejected by their first, second or third owners. I find these the most interesting places to source garments from as they are in the process of becoming obsolete but often are still in great condition, hardly worn, often with tags still on them.

By looking extensively at what is no longer desirable, I learn a lot about psychological obsolescence as well as the material trajectories of garments. When they are discarded for good, they enter a different realm. In a way, my work is not about waste in the sense of garbage or debris but more about the extremities in volume and the speed at which fashion is produced, consumed and discarded.

Installation view of Tenant of Culture, ’Soft Acid’ at Camden Art Centre

W*: You confront themes of waste, and mass consumerism, particularly concerning fast fashion, and the invisible, exploitative economies that support it. As conversations around sustainability in fashion and beyond continue to escalate, what do you hope viewers will take away from your work?

ToC: It’s great that there is currently a lot of interest in these subjects from the consumer side. It is crucial to have these conversations. It is also important to realise that regardless of this, the industry continues to grow exponentially and the number of garments created each year continues to rise. Therefore, I think it is important to specifically address the production side of things and the structures that enabled this industry to accelerate beyond comprehension. Shifting the blame to consumers is a strategy that benefits the producing entities. To rethink consumption we need to begin by understanding the hierarchical relationships between supply and demand.

Tenant of Culture, Sample Sale (series), 2018. Recycled shoes and socks, laces, plaster, tiles, grout.

Tenant of Culture, Flash s/s (Series), 2020, Recycled shoes, garments and bag, elastic, padding, buttons, thread, steel.

Tenant of Culture, Country Styles for the Young, 2020, Recycled clog-style shoes, cement, yarn, rope and cork.

INFORMATION

Tenant of Culture 8 July-18 September 2022, Camden Art Centre, London. camdenartcentre.org

Harriet Lloyd-Smith was the Arts Editor of Wallpaper*, responsible for the art pages across digital and print, including profiles, exhibition reviews, and contemporary art collaborations. She started at Wallpaper* in 2017 and has written for leading contemporary art publications, auction houses and arts charities, and lectured on review writing and art journalism. When she’s not writing about art, she’s making her own.

-

This year's best luxury Christmas hampers for festive celebrations

This year's best luxury Christmas hampers for festive celebrationsThe best Christmas hampers are a classic gift for a reason: everyone loves receiving a basket of beautifully curated pantry fillers just in time for the festivities. Here are our top picks for 2024

By Rosie Conroy Published

-

17 questions for Michael Kiwanuka

17 questions for Michael KiwanukaAs he prepares to release his fourth album 'Small Changes', we ask Michael Kiwanuka some of life's important questions

By Charlotte Gunn Published

-

Inside ‘M&OTHERS’, the experimental exhibition dissecting the relationship between fashion and motherhood

Inside ‘M&OTHERS’, the experimental exhibition dissecting the relationship between fashion and motherhoodA new exhibition at Modemuseum Hasselt, Belgium explores the rarely examined link between fashion and motherhood, in all its forms

By Dal Chodha Published

-

Inside Jack Whitten’s contribution to American contemporary art

Inside Jack Whitten’s contribution to American contemporary artAs Jack Whitten exhibition ‘Speedchaser’ opens at Hauser & Wirth, London, and before a major retrospective at MoMA opens next year, we explore the American artist's impact

By Finn Blythe Published

-

Doc'n Roll Film Festival makes its loud return to the UK

Doc'n Roll Film Festival makes its loud return to the UKThe 11th edition of the Doc'n Roll Film Festival celebrates music, culture and cinema from around the world

By Smilian Cibic Published

-

Preview the Jameel Prize exhibition, coming to London's V&A, with a focus on moving image and digital media

Preview the Jameel Prize exhibition, coming to London's V&A, with a focus on moving image and digital mediaThe winner of the V&A and Art Jameel’s seventh international award for contemporary art and design inspired by Islamic tradition will be showcased alongside shortlisted artists

By Smilian Cibic Published

-

Genesis Belanger is seduced by the real and the fake in London

Genesis Belanger is seduced by the real and the fake in LondonSculptor Genesis Belanger’s solo show, ‘In the Right Conditions We Are Indistinguishable’, is open at Pace, London

By Emily Steer Published

-

Francis Bacon at the National Portrait Gallery is an emotional tour de force

Francis Bacon at the National Portrait Gallery is an emotional tour de force‘Francis Bacon: Human Presence’ at the National Portrait Gallery in London puts the spotlight on Bacon's portraiture

By Hannah Silver Published

-

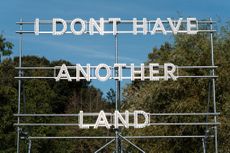

Frieze Sculpture takes over Regent’s Park

Frieze Sculpture takes over Regent’s ParkTwenty-two international artists turn the English gardens into a dream-like landscape and remind us of our inextricable connection to the natural world

By Smilian Cibic Published

-

Meet Oluwole Omofemi and Bayo Akande, the founders creating a new art community

Meet Oluwole Omofemi and Bayo Akande, the founders creating a new art communityOluwole Omofemi and Bayo Akande, are behind Piece Unique, an artist agency that guides and future-proofs emerging artists’ careers

By Mazzi Odu Published

-

Don’t miss these artists at 1-54 Contemporary African Art Fair 2024

Don’t miss these artists at 1-54 Contemporary African Art Fair 2024As the 1-54 Contemporary African Art Fair returns to London (10-13 October 2024), here are the artists to see

By Gameli Hamelo Published