Thao Nguyen Phan at Tate St Ives: a poetic layering of Vietnamese history and ecology

Thao Nguyen Phan’s work intertwines mythology and urgent environmental concerns in her home country of Vietnam. We spoke to the artist about hidden histories and how her largest UK exhibition to date, at Tate St Ives, ‘feels like a recovery’

The Vietnamese artist Thao Nguyen Phan is fond of stories that others don’t want to hear. Stories about the war, for instance. In 1979, after the Vietnamese army overthrew the Khmer Rouge, her uncle went to Cambodia for three years as part of the Vietnamese occupation force. Drained by the genocide, the capital city of Phnom Penh was almost empty of humans, but full of black birds, he told her. In order to take a shower he had to use the water from the well, but whenever he did so, his hair would be covered by white dust.

‘The Khmer Rouge used to throw the dead into the wells,’ the Cambodians told him. ‘The white dust is what remains of the bones.’

Phan’s cousins took little interest in these gruesome stories, but she became fascinated with them. Fuelled by the fact that the Vietnamese occupation of Cambodia was rarely mentioned in Vietnamese history books, she conducted long interviews with her uncle. This inspired her latest work, the video installation First Rain, Brise Soleil (2021– ongoing) in which three films are projected next to each other like a moving, modern-day triptych. Neither the images nor the story told in the subtitles features her uncle’s experience, however. Having explored a hidden side of Vietnamese history, Phan decided to create a new work of fiction: the story of a Vietnamese construction worker who goes to Cambodia in the 18th century and witnesses a great fire that destroys the country’s most magnificent theatre.

Thao Nguyen Phan

‘I’m interested in fiction because I realised at some point that Vietnam itself is like a big fiction,’ she says. ‘You don’t know what´s truthful and what’s not.’

Speaking on Zoom from Cornwall, where she has installed her solo show at Tate St Ives (until 2 May 2022), Phan talks softly, giving off the air of thoughtful observation. At the same time, you can sense her artistic mission to make sense of her country’s past and future; a drive to pose big questions and to present them on a large scale. Phan aims to uncover hidden narratives, to bring them to light in a new way. This makes her work at once very coded and very open; multi-faceted, but also driven by an overarching curiosity that seeks to discover it all: history and religion, nature and civilisation, folklore and art.

Trained in her hometown of Ho Chi Minh City, as well as Singapore and Chicago, Phan, 34, is one of Vietnam’s few contemporary artists to show their work abroad. In 2016 – 17, she was mentored by New York-based artist Joan Jonas as part of the Rolex Mentor and Protégé Arts Initiative. Her Tate St Ives show is her first major solo presentation in the UK, featuring paintings, sculptures and video installations. There are watercolour images drawn on the pages of the book Rhodes of Viet Nam, by the missionary Alexandre de Rhodes, who had adapted the Vietnamese language into the Roman alphabet (Voyages de Rhodes, 2014 – 17). There are light sculptures in sunflower and bird shapes, recalling the traditional symbols of harmony, prosperity and longevity, but also the sunflower motif used for state propaganda (The Rise and The Flower, both 2016). There is another video installation devoted to the Mekong river and the imbalanced relationship between humans and the environment (Becoming Alluvium, 2019 – ongoing).

Thao Nguyen Phan, Voyages de Rhodes 2014 – 17.

‘On first seeing Phan’s work I was struck by the way in which she works across media and methodologies, creating a distinctive artistic language that often layers or blends film and animation, image and text,’ says Anne Barlow, director of Tate St Ives.

Wallpaper* Newsletter

Receive our daily digest of inspiration, escapism and design stories from around the world direct to your inbox.

Phan, who was born the year after the economic liberalisation of socialist Vietnam in 1986, grew up in a country that has been changing rapidly. While Ho Chi Minh City has evolved into a sprawling metropolis with skyscrapers, shopping malls and plenty of cars, modernisation has also posed a threat to the environment. According to the World Bank, the per capita plastic consumption rate in Vietnam rose ten times between 1990 and 2019. Coastlines and rivers – including the mighty Mekong – are heavily polluted. ‘I feel that Vietnamese people are paying a very high price to modernise,’ Phan says. ‘Our children will have to shoulder the burden.’

Environmentalism is an issue that concerns the younger, better-educated generation more than the older one, she admits. Many Vietnamese still focus on providing for their family, especially those living in the countryside. ‘Most people are just too busy making a living,’ she says.

Thao Nguyen Phan, First Rain, Brise Soleil 2021 – ongoing. Made with the support of the Han Nefkens Art Foundation and Tate St Ives.

Now that the Tate St Ives exhibition is opening, Phan says she no longer thinks about her art being from or about Vietnam. She feels she has come full circle. Her last show opened at the Wiels Contemporary Art Centre in Brussels in February 2020. Before she flew back to Vietnam, her mother asked her to buy face masks because they were already sold out at home. The 20 months that followed felt frozen in time: Phan finished her work on First Rain, Brise Soleil during a strict lockdown and shortly after giving birth to her second child. Her seven-year-old daughter couldn’t go to school and spent her days being bored at home. Phan’s favourite Vietnamese art space, The Factory, had to close temporarily because the people who ran it moved on to other jobs or other countries.

Now, finally, Phan can travel and show her work again. ‘It’s a good return after almost two years of silence,’ Phan says. ‘It feels like a recovery.’

Thao Nguyen Phan, Becoming Alluvium (video still) 2019. Produced and commissioned by Han Nefkens Foundation in collaboration with: Joan Miró Foundation, Barcelona; WIELS Contemporary Art Centre, Brussels; and Chisenhale Gallery.

Thao Nguyen Phan, First Rain, Brise Soleil (video still) 2021 – ongoing . Made with the support of the Han Nefkens Art Foundation and Tate St Ives

Thao Nguyen Phan, The Flower, 2016.

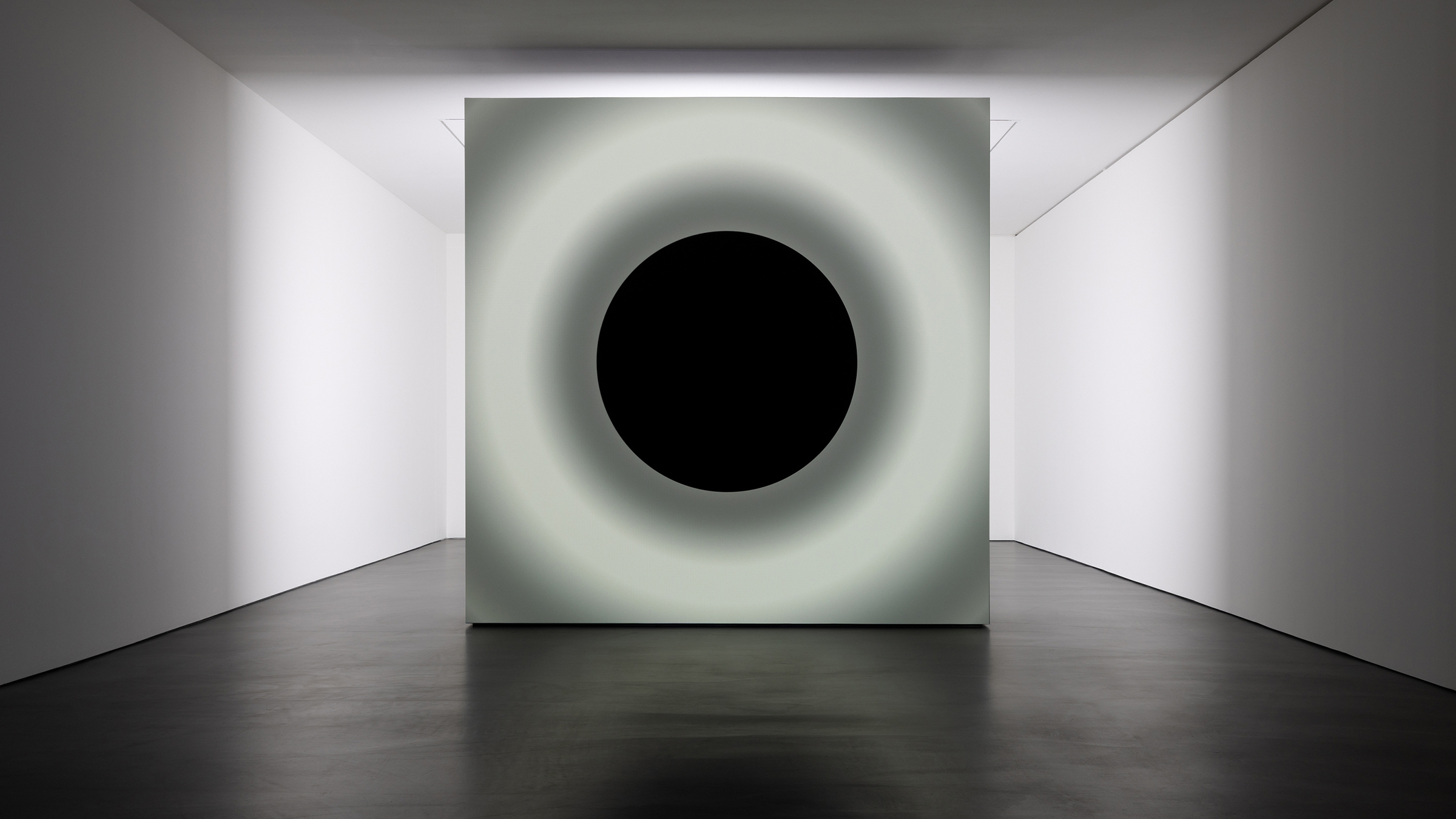

Thao Nguyen Phan, installation view at Tate St Ives, 2022.

INFORMATION

Thao Nguyen Phan’s exhibition at Tate St Ives will be on view until 2 May 2022. tate.org.uk

About the author

Khue Pham is an award-winning Vietnamese-German writer. A graduate from the LSE, she has contributed to the UK’s Guardian and NPR before becoming an editor at the renowned German weekly Die ZEIT. Her interests span pop culture and politics; she has interviewed Anna Wintour; and her investigative reporting has earned her a nomination for the prestigious Egon Erwin Kisch Prize. In 2012, she co-wrote a non-fiction book about second-generation immigrants in Germany. In 2021, she published her first novel Brothers and Ghosts, which is inspired by the story of her Vietnamese family.

-

All-In is the Paris-based label making full-force fashion for main character dressing

All-In is the Paris-based label making full-force fashion for main character dressingPart of our monthly Uprising series, Wallpaper* meets Benjamin Barron and Bror August Vestbø of All-In, the LVMH Prize-nominated label which bases its collections on a riotous cast of characters – real and imagined

By Orla Brennan

-

Maserati joins forces with Giorgetti for a turbo-charged relationship

Maserati joins forces with Giorgetti for a turbo-charged relationshipAnnouncing their marriage during Milan Design Week, the brands unveiled a collection, a car and a long term commitment

By Hugo Macdonald

-

Through an innovative new training program, Poltrona Frau aims to safeguard Italian craft

Through an innovative new training program, Poltrona Frau aims to safeguard Italian craftThe heritage furniture manufacturer is training a new generation of leather artisans

By Cristina Kiran Piotti

-

Remote Antarctica research base now houses a striking new art installation

Remote Antarctica research base now houses a striking new art installationIn Antarctica, Kyiv-based architecture studio Balbek Bureau has unveiled ‘Home. Memories’, a poignant art installation at the remote, penguin-inhabited Vernadsky Research Base

By Harriet Lloyd-Smith

-

Ryoji Ikeda and Grönlund-Nisunen saturate Berlin gallery in sound, vision and visceral sensation

Ryoji Ikeda and Grönlund-Nisunen saturate Berlin gallery in sound, vision and visceral sensationAt Esther Schipper gallery Berlin, artists Ryoji Ikeda and Grönlund-Nisunen draw on the elemental forces of sound and light in a meditative and disorienting joint exhibition

By Harriet Lloyd-Smith

-

Cecilia Vicuña’s ‘Brain Forest Quipu’ wins Best Art Installation in the 2023 Wallpaper* Design Awards

Cecilia Vicuña’s ‘Brain Forest Quipu’ wins Best Art Installation in the 2023 Wallpaper* Design AwardsBrain Forest Quipu, Cecilia Vicuña's Hyundai Commission at Tate Modern, has been crowned 'Best Art Installation' in the 2023 Wallpaper* Design Awards

By Harriet Lloyd-Smith

-

Michael Heizer’s Nevada ‘City’: the land art masterpiece that took 50 years to conceive

Michael Heizer’s Nevada ‘City’: the land art masterpiece that took 50 years to conceiveMichael Heizer’s City in the Nevada Desert (1972-2022) has been awarded ‘Best eighth wonder’ in the 2023 Wallpaper* design awards. We explore how this staggering example of land art came to be

By Harriet Lloyd-Smith

-

Cyprien Gaillard on chaos, reorder and excavating a Paris in flux

Cyprien Gaillard on chaos, reorder and excavating a Paris in fluxWe interviewed French artist Cyprien Gaillard ahead of his major two-part show, ‘Humpty \ Dumpty’ at Palais de Tokyo and Lafayette Anticipations (until 8 January 2023). Through abandoned clocks, love locks and asbestos, he dissects the human obsession with structural restoration

By Harriet Lloyd-Smith

-

Year in review: top 10 art interviews of 2022, chosen by Wallpaper* arts editor Harriet Lloyd-Smith

Year in review: top 10 art interviews of 2022, chosen by Wallpaper* arts editor Harriet Lloyd-SmithTop 10 art interviews of 2022, as selected by Wallpaper* arts editor Harriet Lloyd-Smith, summing up another dramatic year in the art world

By Harriet Lloyd-Smith

-

Cerith Wyn Evans: ‘I love nothing more than neon in direct sunlight. It’s heartbreakingly beautiful’

Cerith Wyn Evans: ‘I love nothing more than neon in direct sunlight. It’s heartbreakingly beautiful’Cerith Wyn Evans reflects on his largest show in the UK to date, at Mostyn, Wales – a multisensory, neon-charged fantasia of mind, body and language

By Harriet Lloyd-Smith

-

The best 7 Christmas installations in London for art lovers

The best 7 Christmas installations in London for art loversAs London decks its halls for the festive season, explore our pick of the best Christmas installations for the art-, design- and fashion-minded

By Harriet Lloyd-Smith