Theaster Gates’ Serpentine Pavilion asks: how do you create a sacred space?

As Chicago-based artist Theaster Gates unveils his much-anticipated Serpentine Pavilion, Black Chapel, he speaks to art historian and curator Aindrea Emelife, who reflects on the space’s power to unify people, cultures and creative disciplines

How do you create a sacred space? Theaster Gates seeks to resolve this question with Black Chapel, his design for this year’s Serpentine Pavilion. It’s a fitting task for the Chicago-based artist, who has received international acclaim for his community and cultural interventions in Black space, particularly on the South Side of Chicago.

Theaster Gates, photographed at his studio on Chicago’s South Side on 3 August 2021.

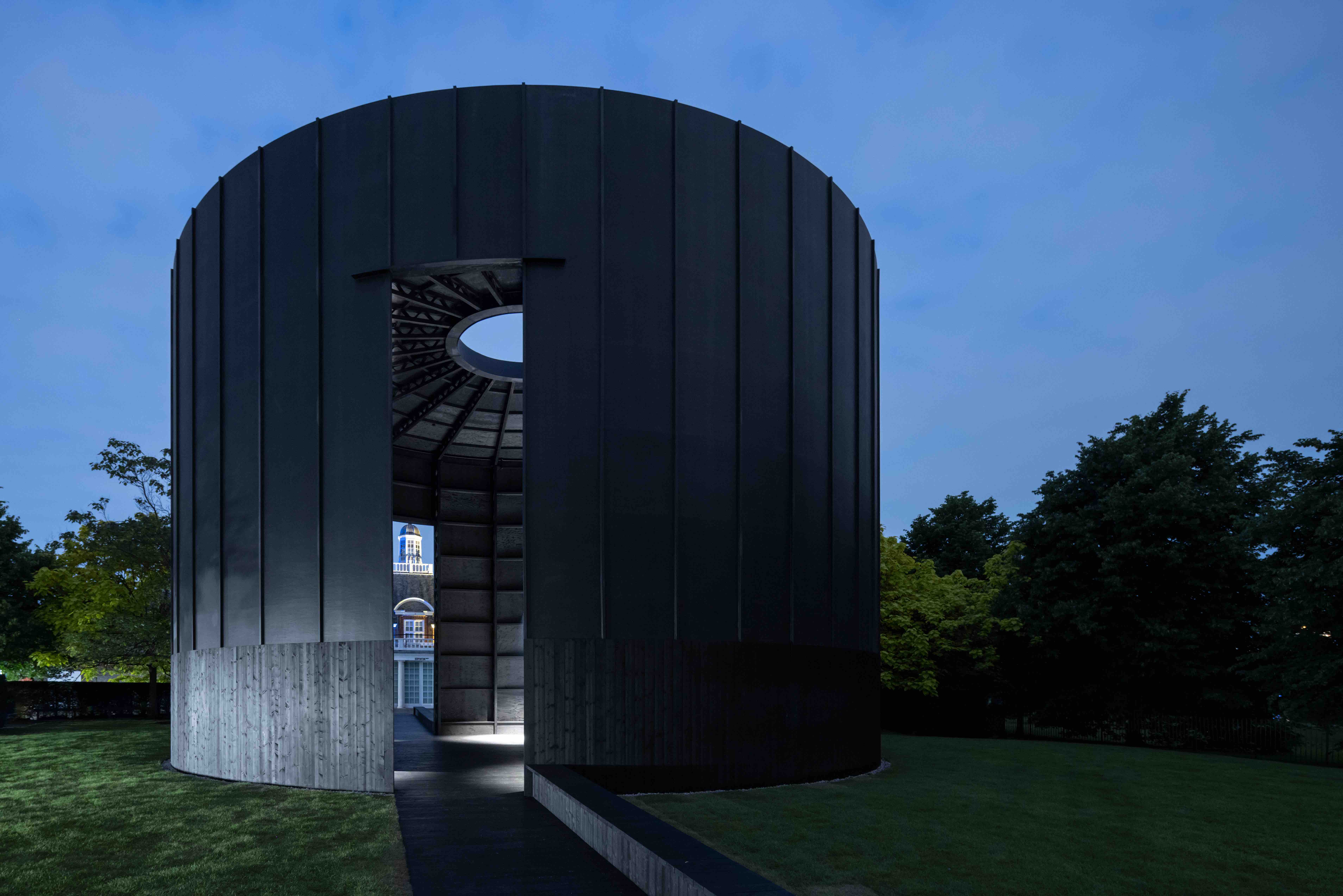

Nestled in London’s Kensington Gardens, the monumental black pavilion, realised with architecture studio Adjaye Associates, at once conjures up traditional concepts of the chapel, but also is securely rooted in the ideas of monumentality, taking up space, and disruption by way of creating peace and tranquillity. Instantly imposing, yet quietly meditative, it is a confident and sure statement and testament to Black communities, encouraging quietude, reflection and a retreat to nature. ‘I hope that folks from further afield than Hyde Park can find solace in this space,’ says Gates. Standing in his chapel, looking up at the oculus, it feels apt to transport oneself back in time and consider the Pantheon.

The Pantheon, completed around 126-128 AD during the reign of Emperor Hadrian, is one of the best-preserved monuments of ancient Rome, with its focal feature being a rotunda with a massive domed ceiling that has formed a lasting inspiration in the minds of artists and architects alike. The largest structure of its kind when it was built, the Pantheon is situated where an earlier structure with the same name, built around 25 BC by Marcus Agrippa, once stood. It is thought to have been designed as a temple for the gods.

Serpentine Pavilion 2022 designed by Theaster Gates © Theaster Gates Studio. Courtesy: Serpentine

At 16m in diameter and 10.7m high, Gates’ chapel is the largest Serpentine Pavilion to date, with a 201 sq m cylinder that dominates with formidable yet comforting grace. Gates’ architectural references include the beehive kilns of the American West, the traditional forms of Cameroon’s Musgum mud huts, Uganda’s Kasubi Tombs, and industrial structures such as bottle kilns in Stoke-on-Trent (the heart of the British ceramic industry).

Here, Gates draws on his own ceramic practice whilst connecting with the history of religious structures such as a 16th-century Tempietto in Rome designed by Donato Bramante, the Umbrian architect who would later design St Peter’s Basilica in the Vatican. Meaning ‘little temple’ the Tempietto is a small, circular church whose design mixes the aesthetic intentions of sculpture with the spiritual ideals of an ancient pagan temple, resting heavily on and honouring Classical aesthetics – a style popular during the Italian Renaissance, and assuring harmony and order. The elements are mathematically proportioned, a unity and simplicity also achieved in Gates’ investigations into clay. Black Chapel fuses spirituality with a multicultural High Renaissance.

Serpentine Pavilion 2022 designed by Theaster Gates © Theaster Gates Studio. Courtesy: Serpentine

The concept of a sacred space finds its origins in the very beginnings of civilisation, with iterations and reimaginings appearing in various cultures. It is significant – a universal construct that proves its necessity and healing power in its prominence and recalibration throughout history. Sacred spaces such as Black Chapel introduce meaningful experiences to the vast, homogenous expanse that city life can envelop us in.

Who are Gates’ gods? ‘I want to encourage Black presence,’ he asserts.

Wallpaper* Newsletter

Receive our daily digest of inspiration, escapism and design stories from around the world direct to your inbox.

Gates, through a robust set of programming curated with the Serpentine, will activate the Chapel. And so we witness a hierophany, as interventions and activations of the pavilion seek to fundamentally alter our relationship with space and time. The measure of any architectural structure is its ability to transcend the contemporary and the historical, to transport those within into a world of the artist's design, and thus achieve a purpose. For Gates, this is to give form and space to Black meditative sound, convert the monastic to the contemporary and, as he divulges, ‘encourage ideas about performance and aesthetic traditions’.

Serpentine Pavilion 2022 designed by Theaster Gates © Theaster Gates Studio. Courtesy: Serpentine

As is typical in Gates’ practice, music is a fundamental component of the pavilion, which will host church choirs, experimental piano composers, and jazz musicians, building up to October’s closing performances by Grammy award-winning singer Corinne Bailey Rae and Gates’ ensemble The Black Monks, whose music offers a powerful celebration of Eastern monastic sound with the soulful musical backbone of the American South. Sitting outside the chapel is a large bronze bell, salvaged from St Laurence, a demolished Catholic church and landmark of Chicago’s South Side. Gates is known for excavating abandoned buildings such as St Laurence for new meaning, and previously exhibited a statue of the patron saint.

For his pavilion, Gates was inspired by the ‘transcendental environment’ of the Rothko Chapel in Houston, Texas – home to 14 dark-hued paintings by abstract expressionist Mark Rothko. Gates’ new series of seven tar paintings – using layered, blow-torched roofing materials that reference his late father’s trade as a roofer – live in his Black Chapel. The artist knows that light is powerful. The history of the Rothko Chapel set an artistic precedent for this lesson: for almost five decades, the light in this chapel was not right. The Texas sun blasted through the original transparent skylight, obliterating the vision of dusky paintings and hindering the spiritual encounter Rothko envisioned for the space.

In Black Chapel, Gates has achieved a resolve and a future-thinking piece that honours many legacies. The oculus anointing us with grey London light is a poignant reminder of the power of nature, and of looking up. It is a window to consider an ever-changing world; as sunlight brings joy, and the nocturnal sky fascinates with a sense of the unknown, we too can be blinded by the light, and overpowered by nature. Historically, religions have used these experiences of light to emphasise the mysticism of their deities, echoing this idea in the design of buildings. Here, Gates encourages us to consider the mysticism of contemporary life.

Serpentine Pavilion 2022 designed by Theaster Gates © Theaster Gates Studio. Courtesy: Serpentine

The interaction of lightness and blackness in the chapel thus conjures a socio-political juxtaposition and focus. Bathed in the grey-white light from our cloudy skies, it is a place for all to congregate, and a welcoming gesture to the Black community. Looking up, we consider all that we hope for. We all look at the same sky – we always have.

Gates’ chapel is a unifying devotion to the spiritual as a force to connect, provide safety, and encourage thinking beyond the limits of this world. Urgent and politically ambitious, Black Chapel believes in inspiration and healing as a catalyst for progression. Gates, who is dedicated to a social practice that revives communities, has brought his spirit to London. Let the legacy unfold.

Theaster Gates, Gone Are The Days of Shelter and Martyr, 2014 (still) Video, color, sound, 6 min. 31 sec. © Theaster Gates. Courtesy of Theaster Gates Studio

Theaster Gates, Black Vessel for a Saint, 2017. Courtesy Walker Art Center, Minneapolis.

INFORMATION

Black Chapel is on view at the Serpentine in Kensington Gardens until 16 October 2022. serpentinegalleries.org

-

Inside the Shakti Design Residency, taking Indian craftsmanship to Alcova 2025

Inside the Shakti Design Residency, taking Indian craftsmanship to Alcova 2025The new initiative pairs emerging talents with some of India’s most prestigious ateliers, resulting in intricately crafted designs, as seen at Alcova 2025 in Milan

By Henrietta Thompson Published

-

Tudor hones in on the details in 2025’s new watch releases

Tudor hones in on the details in 2025’s new watch releasesTudor rethinks classic watches with carefully considered detailing – shop this year’s new faces

By Thor Svaboe Published

-

2025 Expo Osaka: Ireland is having a moment in Japan

2025 Expo Osaka: Ireland is having a moment in JapanAt 2025 Expo Osaka, a new sculpture for the Irish pavilion brings together two nations for a harmonious dialogue between place and time, material and form

By Danielle Demetriou Published

-

An octogenarian’s north London home is bold with utilitarian authenticity

An octogenarian’s north London home is bold with utilitarian authenticityWoodbury residence is a north London home by Of Architecture, inspired by 20th-century design and rooted in functionality

By Tianna Williams Published

-

What is DeafSpace and how can it enhance architecture for everyone?

What is DeafSpace and how can it enhance architecture for everyone?DeafSpace learnings can help create profoundly sense-centric architecture; why shouldn't groundbreaking designs also be inclusive?

By Teshome Douglas-Campbell Published

-

The dream of the flat-pack home continues with this elegant modular cabin design from Koto

The dream of the flat-pack home continues with this elegant modular cabin design from KotoThe Niwa modular cabin series by UK-based Koto architects offers a range of elegant retreats, designed for easy installation and a variety of uses

By Jonathan Bell Published

-

Are Derwent London's new lounges the future of workspace?

Are Derwent London's new lounges the future of workspace?Property developer Derwent London’s new lounges – created for tenants of its offices – work harder to promote community and connection for their users

By Emily Wright Published

-

Showing off its gargoyles and curves, The Gradel Quadrangles opens in Oxford

Showing off its gargoyles and curves, The Gradel Quadrangles opens in OxfordThe Gradel Quadrangles, designed by David Kohn Architects, brings a touch of playfulness to Oxford through a modern interpretation of historical architecture

By Shawn Adams Published

-

A Norfolk bungalow has been transformed through a deft sculptural remodelling

A Norfolk bungalow has been transformed through a deft sculptural remodellingNorth Sea East Wood is the radical overhaul of a Norfolk bungalow, designed to open up the property to sea and garden views

By Jonathan Bell Published

-

A new concrete extension opens up this Stoke Newington house to its garden

A new concrete extension opens up this Stoke Newington house to its gardenArchitects Bindloss Dawes' concrete extension has brought a considered material palette to this elegant Victorian family house

By Jonathan Bell Published

-

A former garage is transformed into a compact but multifunctional space

A former garage is transformed into a compact but multifunctional spaceA multifunctional, compact house by Francesco Pierazzi is created through a unique spatial arrangement in the heart of the Surrey countryside

By Jonathan Bell Published