Thomas Demand explores artistic ownership at Fondazione Prada

At what point does appropriation become theft? If an act of theft is artistic enough, is it acceptable? Can any art form exist without borrowing from elsewhere?

These are the questions raised by 90 works at a new exhibition curated by Thomas Demand at Fondazione Prada, Milan. The works – dating back to 1820, right up to the present – prove that these questions on authorship, ownership and creativity have a long history in art practice, and with the vast proliferation of free information and images on the net, they’re even more of a preoccupation for artists – and viewers – to address in the present.

Carved into three overarching sections, L’Image Volee (The Stolen Image) deals with the physical and conceptual contemplations of the theme. First off, Demand has pulled together works that explicitly refer to the criminal act of stealing – or that commit a theft in order to make their art. This includes a work by American artist Richard Artschwager (known for his architectural motifs and Formica works). Artschwager commissioned his work – a Persian carpert entitled Stolen Rug, 1969 – to be stolen from the exhibition in which it was to appear in Chicago. Other pieces, such as Richter-Modell (interconti), 1987 – a coffee table made from a Richter painting by Martin Kippenberger – present works literally made from existing art works.

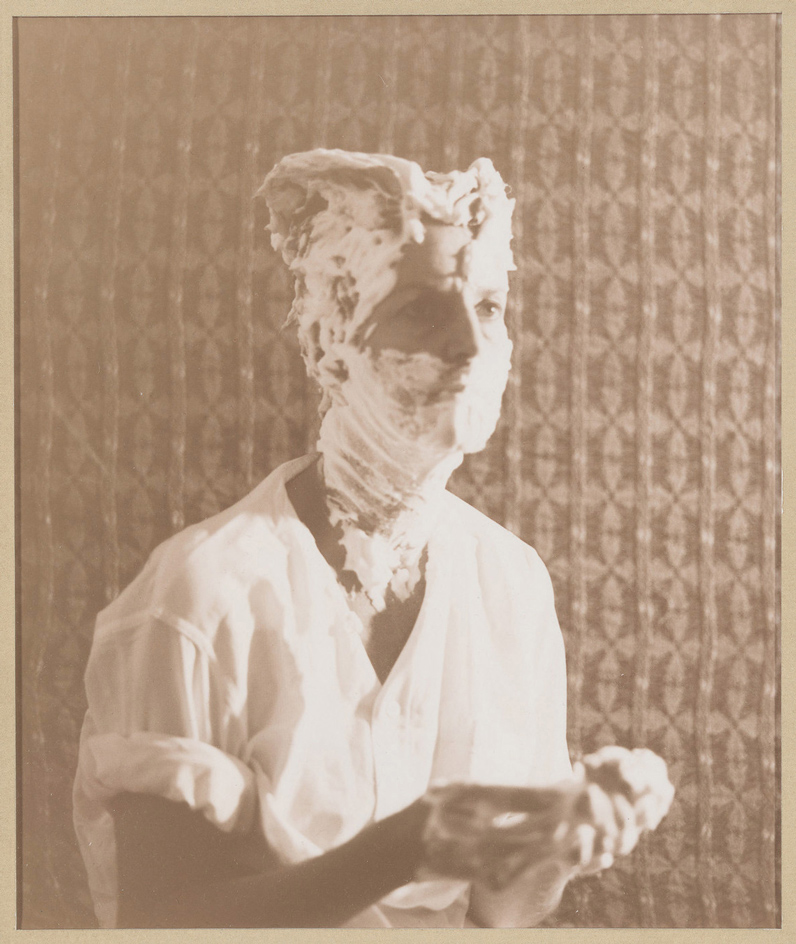

This leads neatly on to artists who re-make other artists’ artwork. Confused? That’s part of the effect of Appropriation Art such as Elaine Sturtevant’s Duchamp Man Ray Portrait, a piece from 1966, which creates a sense of vertigo that is not unlike the feeling of endlessly scrolling on the Internet.

Appropriation is discussed too in the collages of John Stezaker and Wangechi Mutu.

At a certain point, the spectator becomes the spectated. Of the works to watch out for are Baldessari’s Blue Line (Holbein) installation, 1988, fitted with a hidden camera that takes pictures of visitors; and Sophie Calle’s L’Hotel – stealthy shots the artist took of unmade beds and belongings in unoccupied rooms while working as a maid at a hotel in Venice. This section brings the exhibition’s discussion full circle, drawing a parallel between voyeurism and surveillance and the process of observing and making art that is then observed and consumed.

Essentially, the exhibition poses three questions: At what point does appropriation become theft? If an act of theft is artistic enough, is it acceptable? And can any art form exist without borrowing from elsewhere?

Pictured from left to right: Empty frame of Vincent van Gogh’s Portrait of Dr. Gachet, 1890. John Baldessari's 'L’image volée' poster, 2015 – 2016. Stolen Pictures, 1948 Brochure.

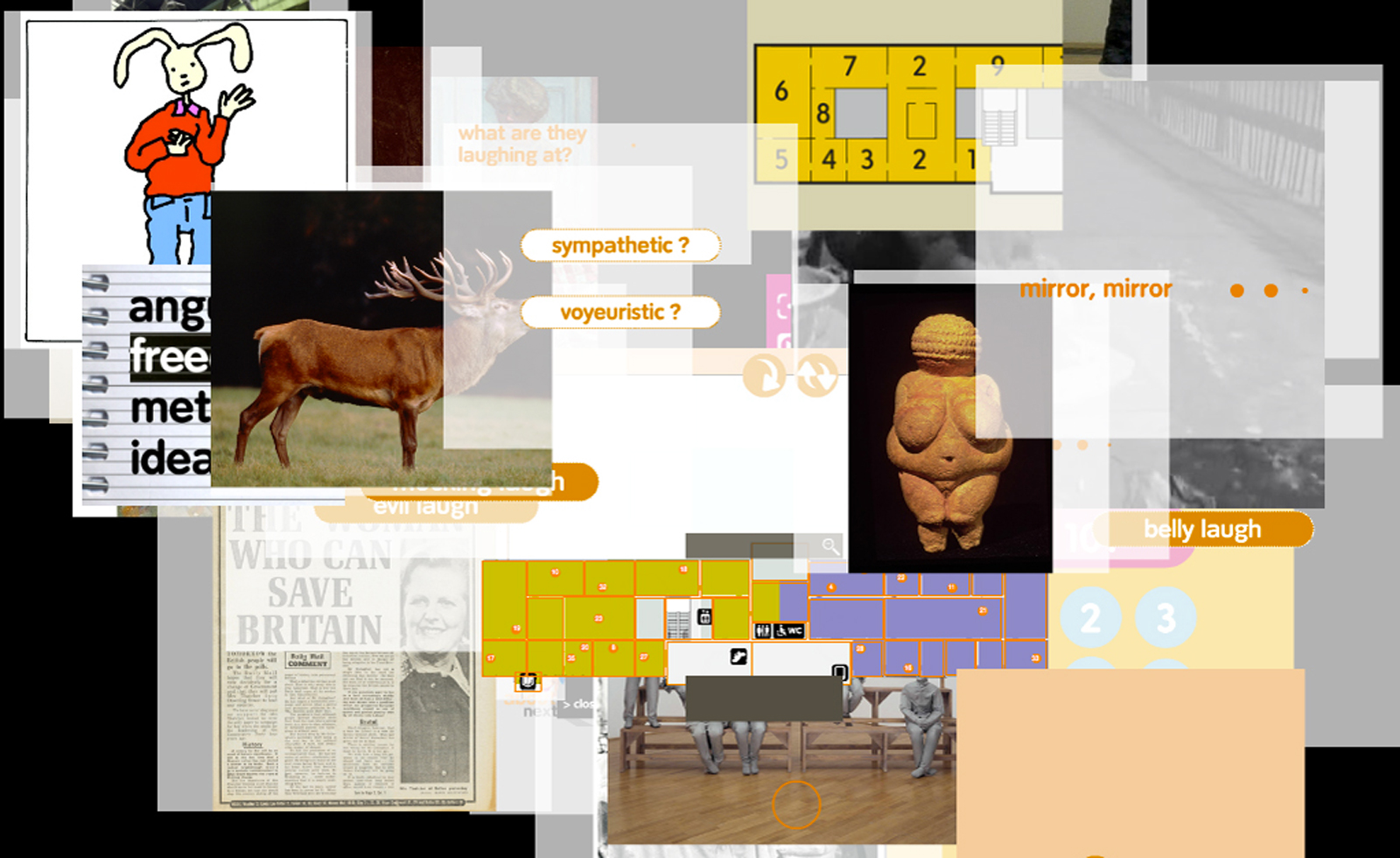

Carved into three overarching sections, L’Image Volee (The Stolen Image) deals with the physical and conceptual contemplations of the theme. Pictured: Untitled #01 t/c, by Haris Epaminonda, 2010.

American artist Richard Artschwager commissioned a Persian carpert – entitled Stolen Rug, 1969 (pictured) – to be stolen from the exhibition in which it was to appear in Chicago. Courtesy of Fondazione Prada

This leads neatly on to artists who re-make other artists’ artwork, aka. Appropriation Art... Pictured: 2 by Henrik Olesen, 2016.

... Like Elaine Sturtevant’s Duchamp Man Ray Portrait (pictured), a piece from 1966, which creates a sense of vertigo that is not unlike the feeling of endlessly scrolling on the Internet.

Appropriation is discussed too in the collages of John Stezaker and Wangechi Mutu. Pictured from left: Oliver Laric's Penelope and Serial Classic.

Of the works to watch out for are Baldessari’s Blue Line (Holbein) installation, 1988, fitted with a hidden camera that takes pictures of visitors. Pictured: Poster for the exhibition 'L’image volée' at Fondazione Prada.

At a certain point, the spectator becomes the spectated, as illustrated by this selection of spyware (Soviet and East German spy equipment) from the Wende Museum in Los Angeles.

INFORMATION

For more information, visit the Fondazione Prada website

ADDRESS

Largo Isarco, 2, 20139 Milano, Italy

Wallpaper* Newsletter

Receive our daily digest of inspiration, escapism and design stories from around the world direct to your inbox.

Charlotte Jansen is a journalist and the author of two books on photography, Girl on Girl (2017) and Photography Now (2021). She is commissioning editor at Elephant magazine and has written on contemporary art and culture for The Guardian, the Financial Times, ELLE, the British Journal of Photography, Frieze and Artsy. Jansen is also presenter of Dior Talks podcast series, The Female Gaze.

-

In search of a seriously-good American whiskey? This is our go-to

In search of a seriously-good American whiskey? This is our go-toBased in Park City, Utah, High West blends the Wild West with sophistication and elegance

By Melina Keays Published

-

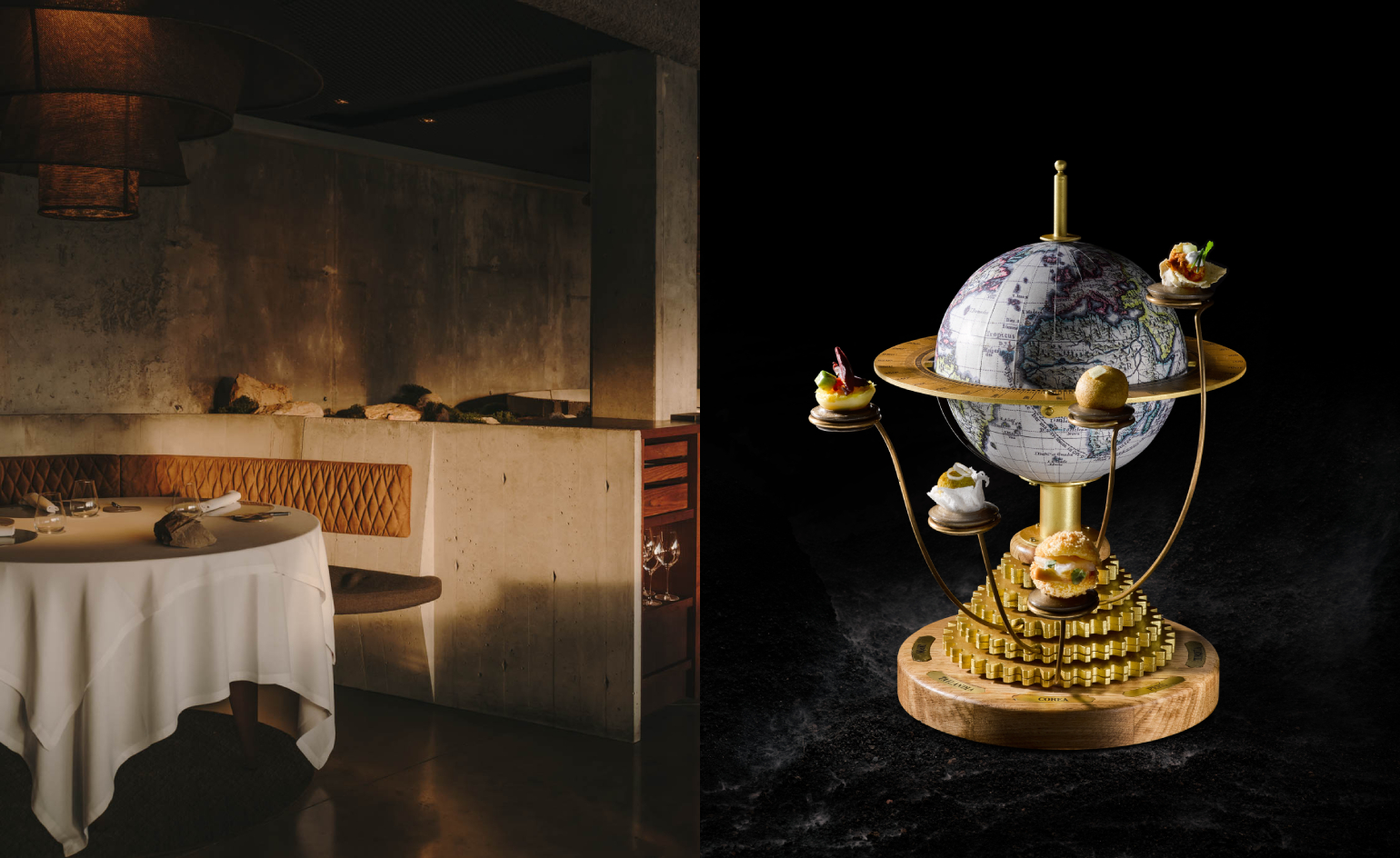

Esperit Roca is a restaurant of delicious brutalism and six-course desserts

Esperit Roca is a restaurant of delicious brutalism and six-course dessertsIn Girona, the Roca brothers dish up daring, sensory cuisine amid a 19th-century fortress reimagined by Andreu Carulla Studio

By Agnish Ray Published

-

Bentley’s new home collections bring the ‘potency’ of its cars to Milan Design Week

Bentley’s new home collections bring the ‘potency’ of its cars to Milan Design WeekNew furniture, accessories and picnic pieces from Bentley Home take cues from the bold lines and smooth curves of Bentley Motors

By Anna Solomon Published

-

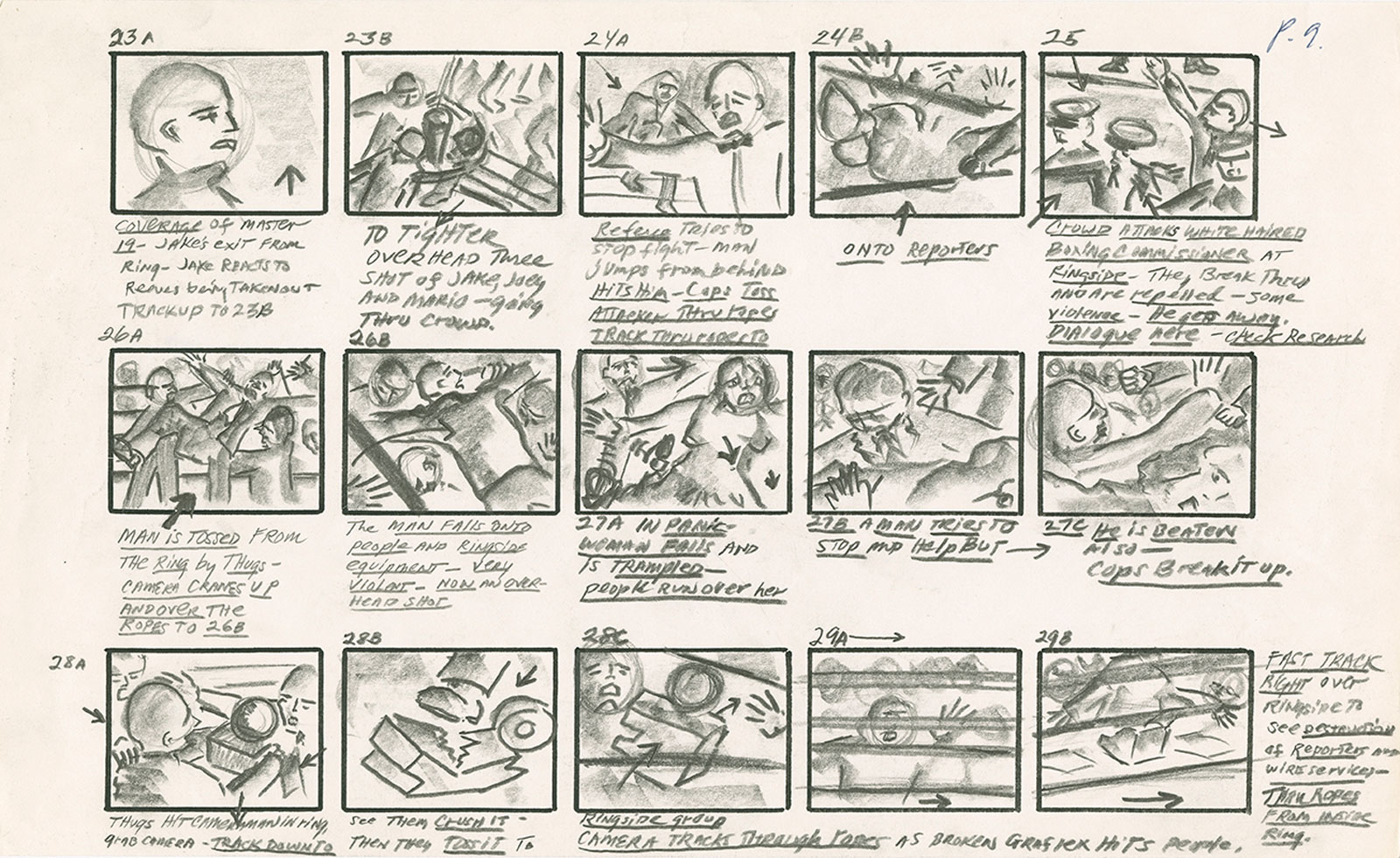

The creative mind at work: a century of storyboarding at Fondazione Prada

The creative mind at work: a century of storyboarding at Fondazione PradaFondazione Prada’s 'Osservatorio, A Kind of Language: Storyboards and Other Renderings' features some of the most celebrated names in cinema working from the late 1920s up to 2024

By Mary Cleary Published

-

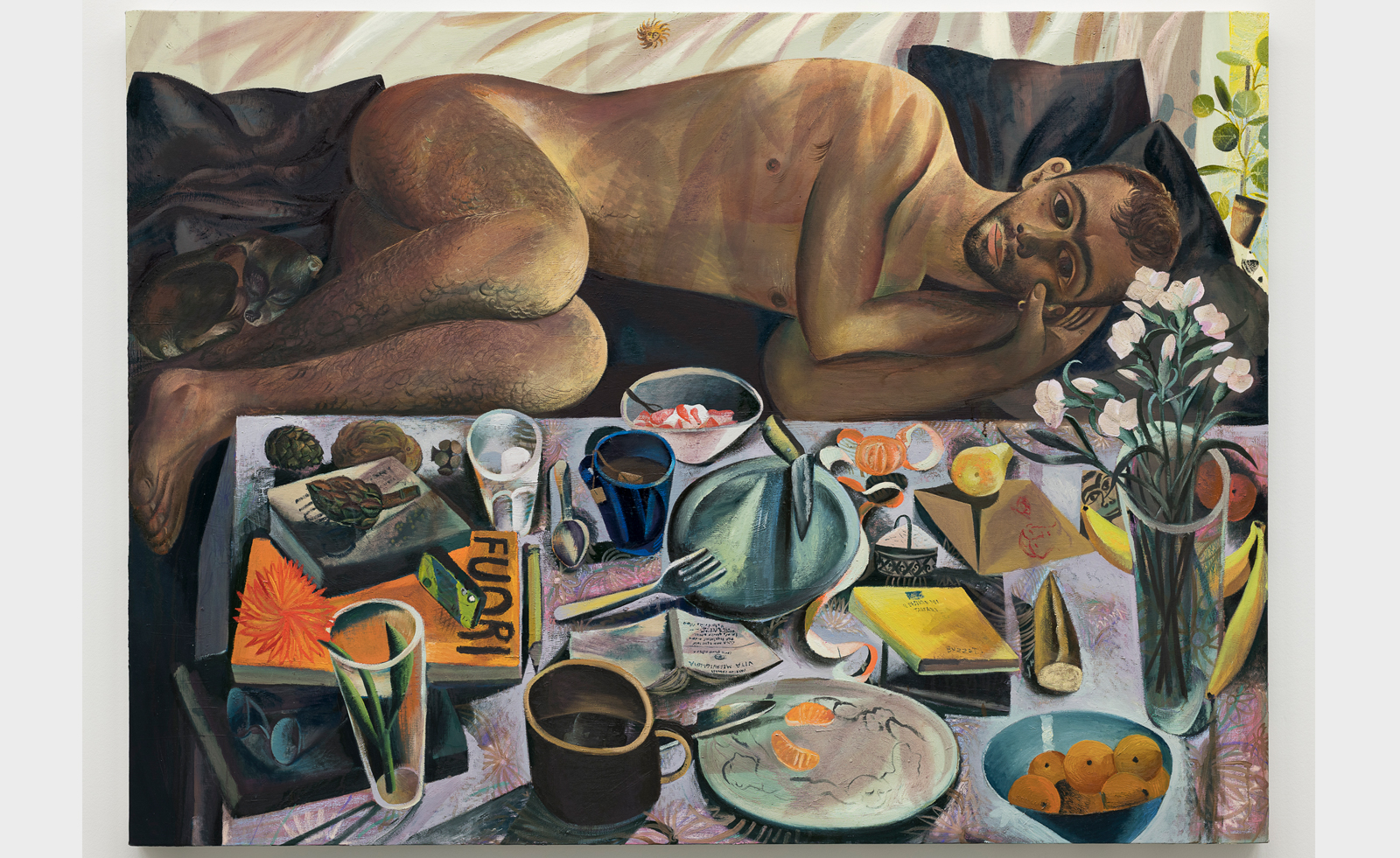

Louis Fratino leans into queer cultural history in Italy

Louis Fratino leans into queer cultural history in ItalyLouis Fratino’s 'Satura', on view at the Centro Pecci in Italy, engages with queer history, Italian landscapes and the body itself

By Sam Moore Published

-

Pino Pascali’s brief and brilliant life celebrated at Fondazione Prada

Pino Pascali’s brief and brilliant life celebrated at Fondazione PradaMilan’s Fondazione Prada honours Italian artist Pino Pascali, dedicating four of its expansive main show spaces to an exhibition of his work

By Kasia Maciejowska Published

-

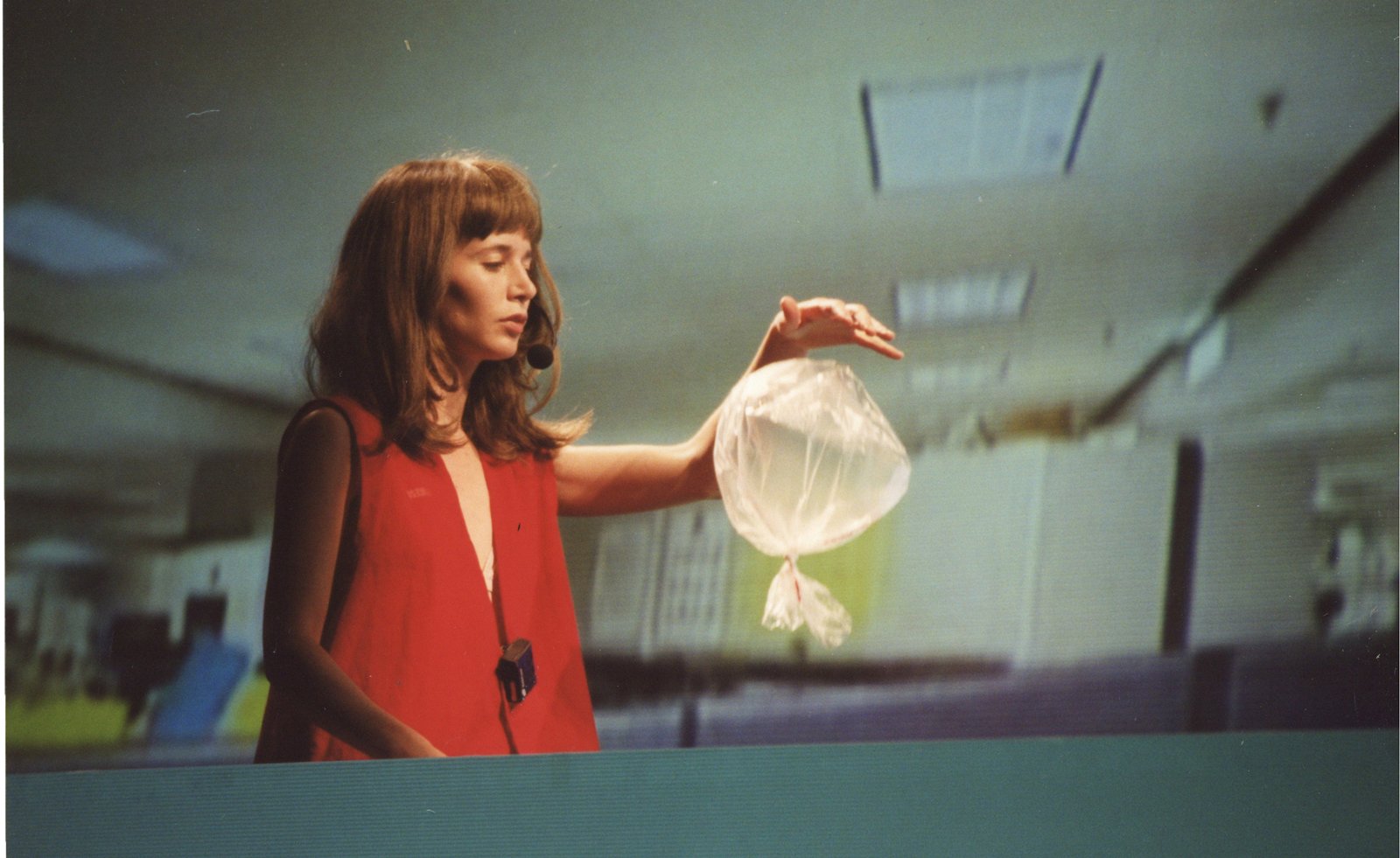

‘I just don't like eggs!’: Andrea Fraser unpacks the art market

‘I just don't like eggs!’: Andrea Fraser unpacks the art marketArtist Andrea Fraser’s retrospective ‘I just don't like eggs!’ at Fondazione Antonio dalle Nogare, Italy, explores what really makes the art market tick

By Sofia Hallström Published

-

Miranda July considers fantasy and performance at Fondazione Prada

Miranda July considers fantasy and performance at Fondazione Prada‘Miranda July: New Society’ at Fondazione Prada, Milan, charts 30 years of the artist's career

By Mary Cleary Published

-

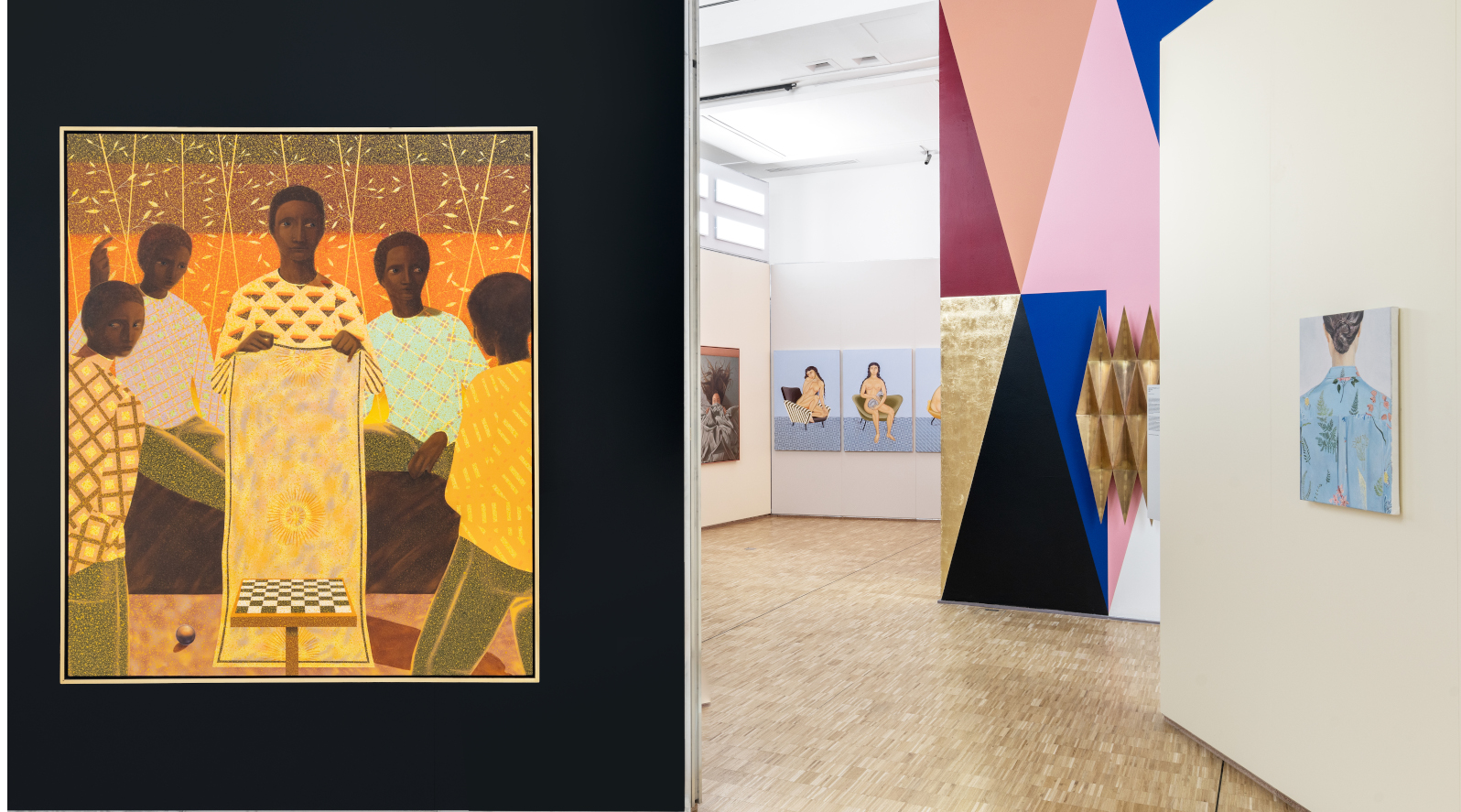

Triennale Milano exhibition spotlights contemporary Italian art

Triennale Milano exhibition spotlights contemporary Italian artThe latest Triennale Milano exhibition, ‘Italian Painting Today’, is a showcase of artworks from the last three years

By Tianna Williams Published

-

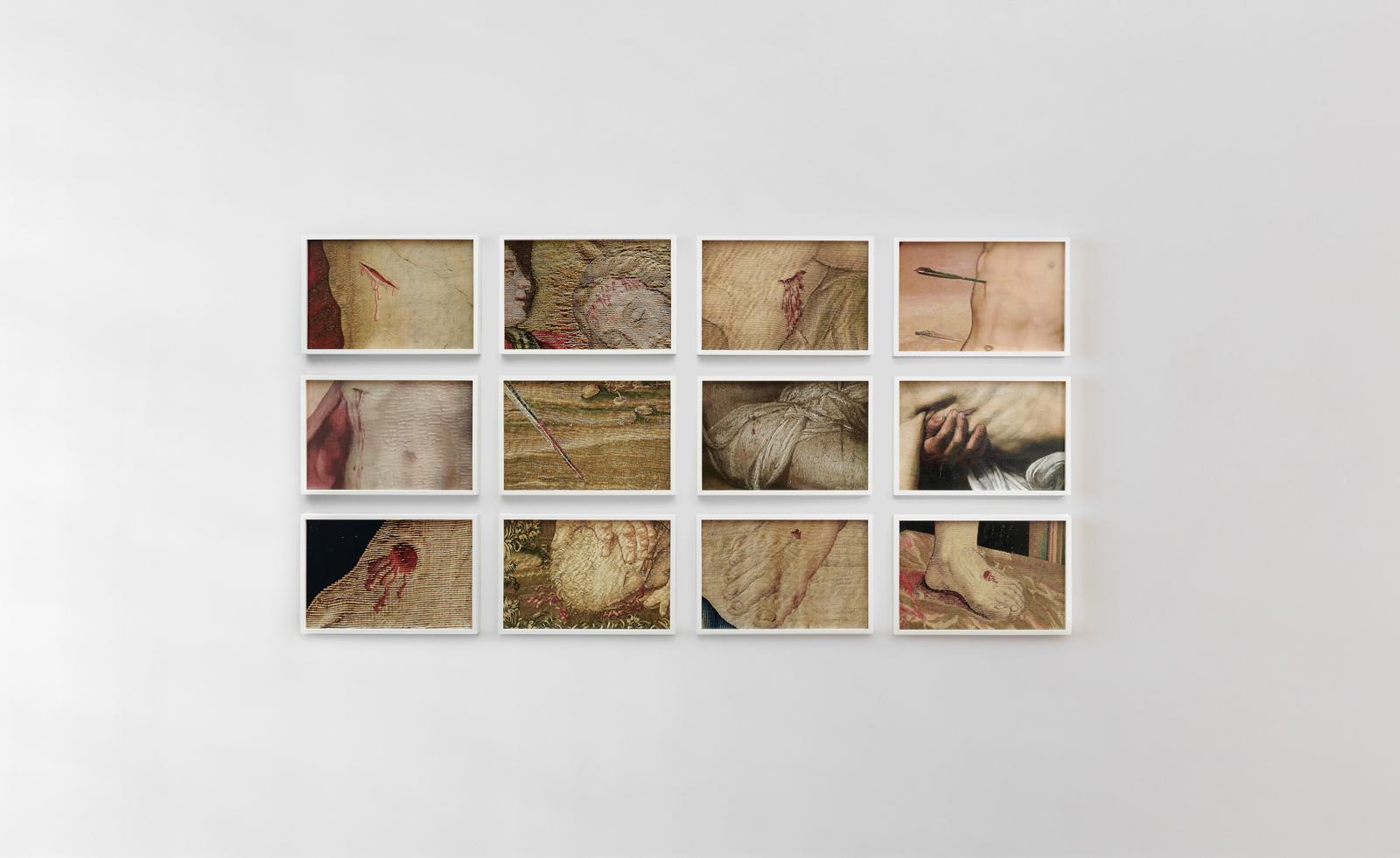

Walls, Windows and Blood: Catherine Opie in Naples

Walls, Windows and Blood: Catherine Opie in NaplesCatherine Opie's new exhibition ‘Walls, Windows and Blood’ is now on view at Thomas Dane Gallery, Naples

By Amah-Rose Abrams Published

-

Venice Biennale 2022 closing review: who, how and what on earth?

Venice Biennale 2022 closing review: who, how and what on earth?As the sun sets on the 59th Venice Art Biennale (until 27 November), we look back on an edition filled with resilience, female power and unsurprisingly, lots of surprises

By Harriet Lloyd-Smith Published