The Chemical Brothers’ Tom Rowlands on creating an electronic score for historical drama, Mussolini

Tom Rowlands has composed ‘The Way Violence Should Be’ for Sky’s eight-part, Italian-language Mussolini: Son of the Century

Tom Rowlands, one half of The Chemical Brothers, is reflecting on possibly the unlikeliest commission of his career: the largely electronic score to a historical drama about the rise, a century ago, of Mussolini.

Specifically, we’re talking about the musician’s composition ‘The Way Violence Should Be’. It’s an instrumental passage that accompanies a key scene in Sky’s eight-part, Italian-language Mussolini: Son of the Century. In a soundtrack that amplifies the drama in a TV series busy with the brutality and bloodshed that attended the birth of fascism in Italy, the paradoxically titled piece is a moment of symphonic calm.

That, the dance music don says, is deliberate. It shows the contrast between would-be-dictator Benito Mussolini’s take-no-prisoners lust for power and “the emotional toll being paid by people around that. It’s an important [moment] in the show: it demonstrates that it isn’t just wall-to-wall violence and anger. That’s one of the crazy things about the series. People go to me: ‘Oh does it end with Mussolini swinging from the lamppost?’” he continues, referring to Il Duce’s death at the hands of Italian partisans towards the end of the Second World War. “I tell them: ‘No – it’s seven hours long and it ends with him coming to power [in 1925].’”

Filming on Mussolini

There is, brilliantly and bracingly, “crazy” in every aesthetic aspect of Mussolini: Son of the Century. That’s a top-down edict from the series’ director, Joe Wright (Atonement, Darkest Hour). The Brit was determined to create a period drama that – like the contemporary rise of far-right politics across western democracies – resonated in 2025, particularly for younger audiences. That meant a show that is visually and stylistically “anachronistic”. Rowlands’ modern-sounding, ahistorical soundtrack is perfectly of a piece with that goal.

First and foremost, though, Wright’s mission is evidenced in the kaleidoscopic visual styles he deployed in the making of his biopic. In a bravura feat of high concept filmmaking, the London-born BAFTA-winner shot the series using a mixture of techniques and approaches: on 1920s urban neighbourhoods built from scratch across the backlot and five cavernous hangars at Rome’s famed Cinecittà Studios; on Brechtian-like theatre sets, lead actor Luca Marinelli talking directly to camera; and in front of Europe’s second-largest Volume screen, a giant curved LED wall more usually used for sci-fi dramas such as Star Wars spin-off The Mandalorian.

Joe Wright on the set of Mussolini

“It's basically like a giant television,” Wright explains, “a pixel screen that allowed me to use effects like they would have used in the 1930s and ’40s, such as back projection… And we projected onto it giant blow-ups of Caravaggio paintings and could play scenes in front of those. So it allowed me to create a very modern aesthetic that also was a nod to the [pre-War period].”

That vision – for a historical thriller that, in every aspect, felt alive and resonant and now – led to Wright commissioning Rowlands. They’re longtime friends and collaborators, dating back to the ’90s, to the filmmaker’s early days working with Vegetable Vision, suppliers of visuals to The Chemical Brothers and other ground-zero big beasts of the electronic music scene. That early part of his CV, in turn, part-explains Wright’s desire to mix up the visual styles of his historical drama.

Receive our daily digest of inspiration, escapism and design stories from around the world direct to your inbox.

“I wanted to convey the feeling of the time for a modern audience. And of the dynamism that must have existed. It's difficult for us to get our heads around what it must have been like coming out of the First World War, the horror of that war, and the recent mechanisation of war – and mechanisation spreading into every aspect of their lives. I guess now it's a bit like AI for us, how that's going to creep into everything.

“And coming out of that period [we also have] Futurism, so I wanted to convey the energy of that. But not in a period way. So, the most important choice I made was asking Tom to come and do the music. Once I'd made that decision, it all fitted into place.”

In terms of the mixed visual styles, the series “acknowledges the artifice,” says a 52-year-old who’s made more than his fair share of faithful, “straight” historical pieces, from his 2005 debut Pride and Prejudice to his last feature, Cyrano (2021). Traditionally filmed sequences – set-piece scenes of plotting in backrooms, say, or Mussolini delivering rabble-rousing speeches – are mixed with obviously digitally-enhanced images.

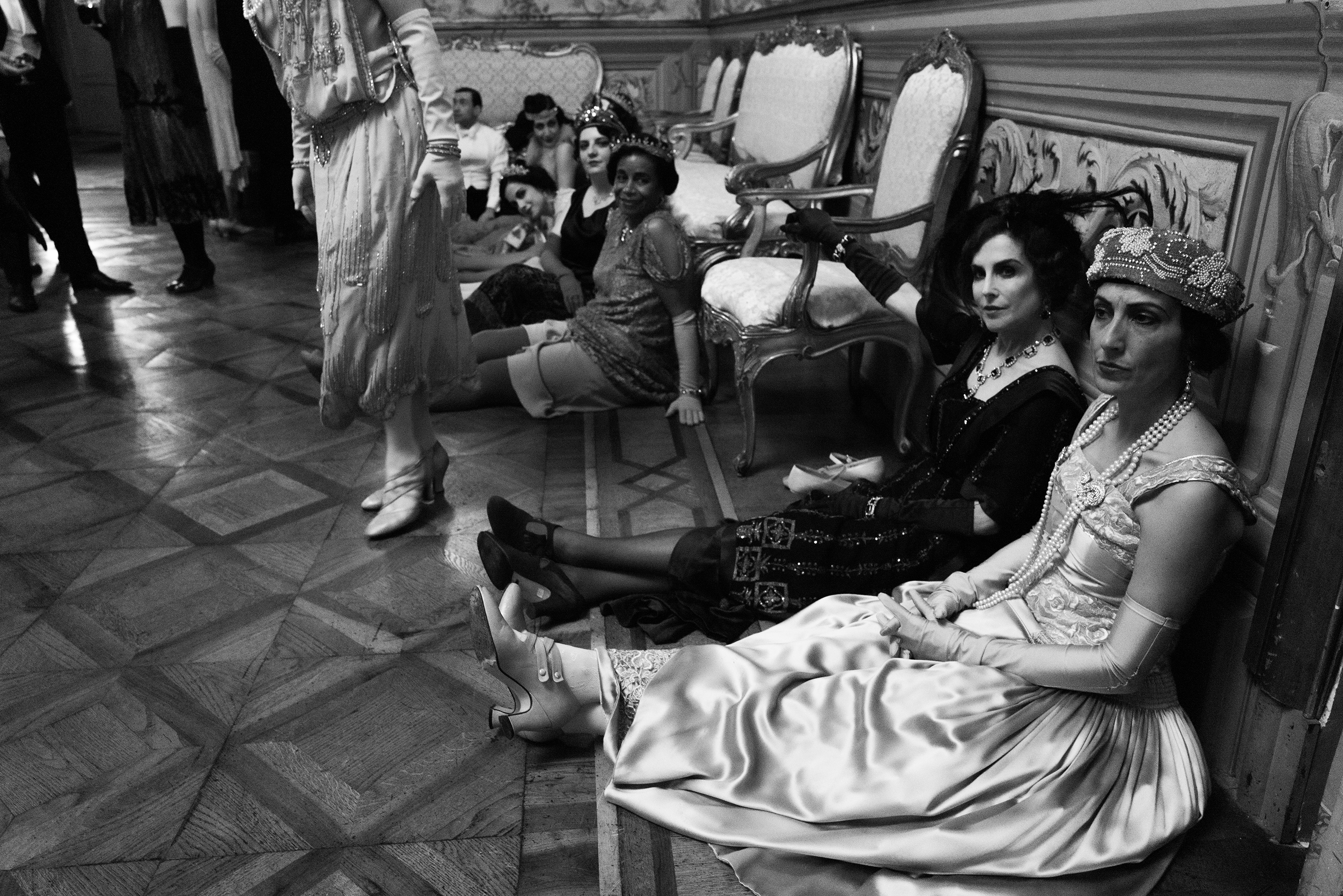

Filming on Mussolini

“It sucks you in, and you feel viscerally draw into the piece,” says Wright of those intense scenes foregrounding dramatic performances from a stellar cast of Italian actors. In contrast, blackly comedic interludes, when Mussolini rants to camera about the frustration of no one taking him seriously, “are moments when it snaps you out of it and says: ‘Why are you laughing at this? Why are you excited by this?’ It somehow challenges the audience’s own reactions and empathy.

Across the narrative's six-year span, and the series' seven-hour run-time, "that Volume stage became really useful in terms [enabling us to] move quite quickly through different atmospheres or environments,” continues Wright. In scenes in Mussolini’s quarters, for example, “we could blow up the [scale of the] wallpaper and create this feeling of him being a tiny little figure against this giant flock wallpaper. It's an exciting tool and something I want to explore more.”

When I visited the Rome set of Mussolini: Son of the Century in April 2023, Wright was deep into production, on day 94 of a shoot that would ultimately last 123 days. Even at that point it was “the record for the longest shoot I’ve done. Most movies, if you’re lucky, are 58. So, this feels like a marathon. And we’re moving at an extraordinary pace.”

The experimental use of Volume, still a relatively new technology for filmmaking, was one reason for that marathon-long sprint. “The LED screen is great for using with the car [journeys],” he said after I’d toured the sets, meaning that Volume could suggest a fast-moving vehicle by showing, through the car windows, rolling images of countryside or Milanese or Roman streets – in theory. “But what we’re playing outside [the windows] isn’t necessarily an attempt at naturalism. We’ve pushed that further and further with using… ’90s rave aesthetics like oil wheels and deeply saturated colours. Then recently we’ve been looking at using AI stuff, which has been a fascinating journey to go on.”

Filming on Mussolini

During a follow-up interview last month, I ask Wright where that AI journey ultimately took him. He replies that, towards the end of the series there is – spoiler alert – not a lamppost scene but “a sequence which a sort of orgy… We played with feeding into AI ideas around [period-specific] images of orgies, bodies and maggots. In the end, we didn't use that much of it,” he notes, which is perhaps just as well.

But while that newest, bleeding-edge iteration of storytelling largely fell by the wayside, there was still room in Mussolini: Son of the Century for one of the oldest styles of narrative presentation. Early on in the drama, in one of those moments that “snap” viewers’ attention, there’s a puppet show. It’s a nod to Wright’s childhood as the son of the owners of the Little Angel Theatre in Islington, North London.

“More than a nod,” he admits. “My mum made the puppets, and my sister operated them. Also, the big figure of Mussolini that's carried down the streets in episode one is the work of my mum and my sister. I always try and involve them in some way. There's not a lot of money in puppetry, so I have to employ them.”

Mussolini: Son of the Century is now viewable on Sky and NOW

London-based Scot, the writer Craig McLean is consultant editor at The Face and contributes to The Daily Telegraph, Esquire, The Observer Magazine and the London Evening Standard, among other titles. He was ghostwriter for Phil Collins' bestselling memoir Not Dead Yet.

-

Modern masters: the ultimate guide to Keith Haring

Modern masters: the ultimate guide to Keith HaringKeith Haring's bold visual identity brought visibility to the marginalised

-

Discover a hidden culinary gem in Melbourne

Discover a hidden culinary gem in MelbourneTucked away in a central Melbourne park, wunderkind chef Hugh Allen’s first solo restaurant, Yiaga, takes diners on a journey of discovery

-

Nina Christen is the designer behind fashion’s favourite – and most playful – shoes

Nina Christen is the designer behind fashion’s favourite – and most playful – shoesShe’s created viral shoes for Loewe and Dior. Now, the Swiss designer is striking out with her own label, Christen

-

A new photo book takes you behind the scenes of some of cinema's most beloved films, from 'Fargo' to 'Charlie's Angels'

A new photo book takes you behind the scenes of some of cinema's most beloved films, from 'Fargo' to 'Charlie's Angels'Set decorator Lauri Gaffin captures Hollywood's quieter moments in an arresting new book

-

Out of office: The Wallpaper* editors’ picks of the week

Out of office: The Wallpaper* editors’ picks of the weekIt’s wet, windy and wintry and, this week, the Wallpaper* team craved moments of escape. We found it in memories of the Mediterranean, flavours of Mexico, and immersions in the worlds of music and art

-

Sean Ono Lennon debuts music video for ‘Happy Xmas (War Is Over)’

Sean Ono Lennon debuts music video for ‘Happy Xmas (War Is Over)’The 11-minute feature, ‘War is Over!’, has launched online; watch it here and read our interview with Sean Ono Lennon, who aimed to make a music video ‘more interesting’

-

Wes Anderson at the Design Museum celebrates an obsessive attention to detail

Wes Anderson at the Design Museum celebrates an obsessive attention to detail‘Wes Anderson: The Archives’ pays tribute to the American film director’s career – expect props and puppets aplenty in this comprehensive London retrospective

-

Out of office: The Wallpaper* editors’ picks of the week

Out of office: The Wallpaper* editors’ picks of the weekThe clocks have gone back in the UK and evenings are officially cloaked in darkness. Cue nights spent tucked away in London’s cosy corners – this week, the Wallpaper* team opted for a Latin-inspired listening bar, an underground arts space, and a brand new hotel in Shoreditch

-

Out of office: the Wallpaper* editors’ picks of the week

Out of office: the Wallpaper* editors’ picks of the weekAs we approach Frieze, our editors have been trawling the capital's galleries. Elsewhere: a 'Wineglass' marathon, a must-see film, and a visit to a science museum

-

Out of office: the Wallpaper* editors’ picks of the week

Out of office: the Wallpaper* editors’ picks of the weekThis week, our editors have been privy to the latest restaurants, art, music, wellness treatments and car shows. Highlights include a germinating artwork and a cruise along the Pacific Coast Highway…

-

Pantone’s new public art installation is a tribute to Coldplay’s ‘Yellow’, 25 years after its release

Pantone’s new public art installation is a tribute to Coldplay’s ‘Yellow’, 25 years after its releaseThe colour company has created a – you guessed it – yellow colour swatch on some steps in Wembley Park, London, where the band will play ten shows this month