Deep web: Tomás Saraceno mines the symbolism of spiders at Palazzo Strozzi

In ‘Aria’, his latest intervention at Palazzo Strozzi, Tomás Saraceno explores environmentalism and urban potential through the ‘wisdom’ of spiders

‘Are you arachnophobic?’ I’m asked before entering ‘Aria’, the new Tomás Saraceno exhibition at Palazzo Strozzi in the heart of Florence.

The Argentine installation artist known for his environmental concerns has turned the webs of spiders into objects of monumental significance – a way to meditate on the ‘new potentials of urbanism’ in an era of ecological upheaval.

Saraceno is using the exhibition to ask: ‘If spiders could speak our human languages, what would they communicate to us?'

The artist keeps many spiders in his Berlin studio. In large glass tanks, he allows different species, sourced from habitats all over the world, to weave their webs together in unison.

Tomás Saraceno, Aria installation at Palazzo Strozzi, Firenze

Once these organic, architectural imaginaria are deemed complete, Saraceno carefully douses the webs with light-sensitive dust. In Florence, in an entirely darkened room, the contents of the glass cases are lit by spotlights installed below.

A single live spider is present to welcome the crowds. He sits entirely still in a humble corner of his web. His legs are as thin as the strands that surround him. He can’t possibly, one assumes, navigate – or even have a concept of – the great world he has created here for us to study. Yet his creation is awe-inspiring. For Saraceno, the tiny spider’s web might allow us to consider ‘another infrastructure, another way of living on this planet.’ They are, he says, potential pointers towards ‘future cities.’

Spiders are feared. Their webs are reflections of our deepest psyche. They haunt our dreams and populate our metaphors, from the ancient myths onwards – like Neith, the Egyptian Goddess of weaving, or the Greek goddess Arachne, who was depicted as half-spider half-human in Gustave Doré's illustration of Dante's Purgatorio.

Today, massive spiders pick their spindly legs between skyscrapers in Hollywood blockbusters or cling to female forms on our advertising hoardings. They have been used, often to terrifying effect, by some of art history’s greatest practitioners. Most notably by Louise Bourgeois as allegories for her abusive mother, but also by Otto Henry Bacher, Vija Celmins and Candace Wheeler, and on film by Ingmar Bergman and Denis Villeneuve.

Tomás Saraceno, Aria installation at Palazzo Strozzi, Firenze

They are carnivorous, granted. They wait for the vibrations of their web, for an unassuming mortal to fly too close, and then spin and wrap their stunned prey in silk. Some have bites that would condemn any of us to a grizzly death. Female variants of some spider species devour their mate, headfirst, as they copulate. It’s easy, on some levels, to see why they’re hated.

But what a tremendously irrational fear. For, when they are not disturbed, spiders are serene beings. In comparison to the devastation humanity wreaks on its common native earthlings on a daily basis, spiders are pacifists. And, as so ably demonstrated by Saraceno, they are architects capable of ‘helping us to radically think about how we can live on this planet.’

RELATED STORY

‘I’m a huge admirer of spiders,’ Saraceno says. ‘And I have for quite some time been studying how they build their webs.’

Most of us, as children, will remember looking upon a spider’s web, heavy with dew, in the morning light. Those memories are evoked by this show. In neighbouring rooms to the real webs, Saraceno has made man-made approximations of webs, now animated by lights and metals and mirrors. In one room, a floor to ceiling structure, made with black rope, knots and metal fastenings you might find in a field at Glastonbury, denotes a spider’s web in human scale, our visible reflection asking us orientate ourselves within this system of strands – perhaps relating to our own existence as individuals caught in a collective system, a literal interweb.

Tomás Saraceno, Aria installation at Palazzo Strozzi, Firenze

It’s almost as if Saraceno is actively trying to draw a comparison – perhaps an unfavourable one – between the creations of nature and our frequent attempts to manufacture artificial facsimiles for own purposes.

Saraceno is happy to frame the exhibition in the rhetoric of environmentalism. At times, these themes are explicit. Pens full of smog from Mumbai are suspended over a white canvas on the end of adjoined strings attached to floating balloons. In another room, a frogs-spawn of glass domes held to the ceiling, house what design boutiques call ‘air plants’, cacti-like foliage, unattached to anything, but somehow, against the odds, alive.

Then there’s a room of sweeping lights and mirrors that throw a kaleidoscope of marbled, moving light-etchings across the wall. It’s a glimpse at a kind of utopia as if we’re above the clouds at first light.

Spiders, Saraceno notes, are able to colonise unlikely places all over the world – whilst always developing and maintaining an equilibrium with their surroundings. Perhaps, Saraceno is suggesting, these creatures, who lurk in the corner of the rooms or become caught in our vacuum cleaners, actually possess great wisdom. Maybe, caught within their webs, are answers to questions that have remained elusive to humanity for so long.

Tomás Saraceno, Aria installation at Palazzo Strozzi, Firenze

If we are to find a way to sustainably exist on this planet whilst also taking care of each other, maybe we could learn to stop fearing the humble spider – and be inspired by them instead.

Wallpaper* Newsletter

Receive our daily digest of inspiration, escapism and design stories from around the world direct to your inbox.

INFORMATION

‘Aria’, until July 19, Palazzo Strozzi

palazzostrozzi.org

ADDRESS

Palazzo Strozzi

Piazza degli Strozzi

50123 Florence

Tom Seymour is an award-winning journalist, lecturer, strategist and curator. Before pursuing his freelance career, he was Senior Editor for CHANEL Arts & Culture. He has also worked at The Art Newspaper, University of the Arts London and the British Journal of Photography and i-D. He has published in print for The Guardian, The Observer, The New York Times, The Financial Times and Telegraph among others. He won Writer of the Year in 2020 and Specialist Writer of the Year in 2019 and 2021 at the PPA Awards for his work with The Royal Photographic Society. In 2017, Tom worked with Sian Davey to co-create Together, an amalgam of photography and writing which exhibited at London’s National Portrait Gallery.

-

Tour the best contemporary tea houses around the world

Tour the best contemporary tea houses around the worldCelebrate the world’s most unique tea houses, from Melbourne to Stockholm, with a new book by Wallpaper’s Léa Teuscher

By Léa Teuscher

-

‘Humour is foundational’: artist Ella Kruglyanskaya on painting as a ‘highly questionable’ pursuit

‘Humour is foundational’: artist Ella Kruglyanskaya on painting as a ‘highly questionable’ pursuitElla Kruglyanskaya’s exhibition, ‘Shadows’ at Thomas Dane Gallery, is the first in a series of three this year, with openings in Basel and New York to follow

By Hannah Silver

-

Australian bathhouse ‘About Time’ bridges softness and brutalism

Australian bathhouse ‘About Time’ bridges softness and brutalism‘About Time’, an Australian bathhouse designed by Goss Studio, balances brutalist architecture and the softness of natural patina in a Japanese-inspired wellness hub

By Ellie Stathaki

-

Remembering Oliviero Toscani, fashion photographer and author of provocative Benetton campaigns

Remembering Oliviero Toscani, fashion photographer and author of provocative Benetton campaignsBest known for the controversial adverts he shot for the Italian fashion brand, former art director Oliviero Toscani has died, aged 82

By Anna Solomon

-

Distracting decadence: how Silvio Berlusconi’s legacy shaped Italian TV

Distracting decadence: how Silvio Berlusconi’s legacy shaped Italian TVStefano De Luigi's monograph Televisiva examines how Berlusconi’s empire reshaped Italian TV, and subsequently infiltrated the premiership

By Zoe Whitfield

-

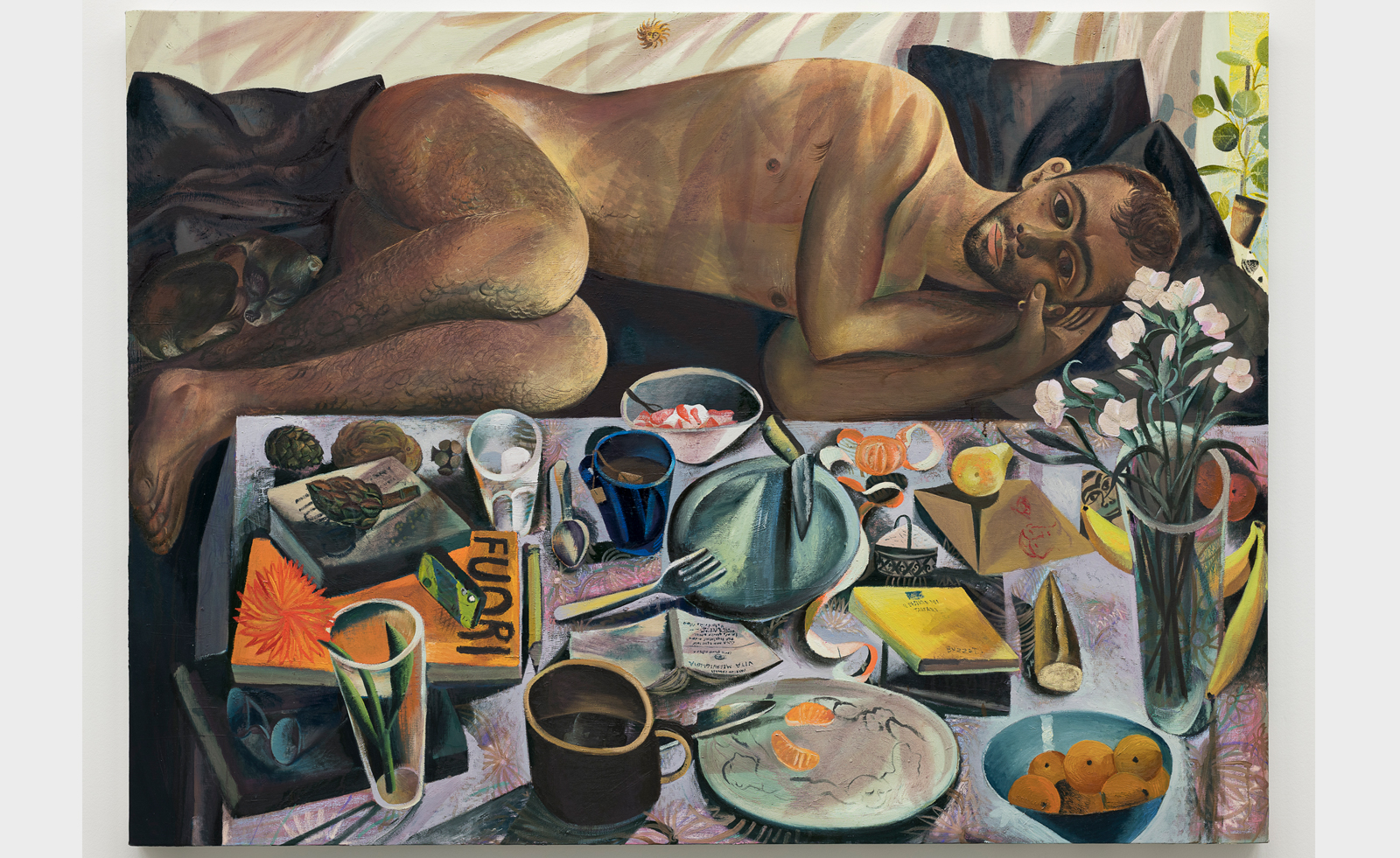

Louis Fratino leans into queer cultural history in Italy

Louis Fratino leans into queer cultural history in ItalyLouis Fratino’s 'Satura', on view at the Centro Pecci in Italy, engages with queer history, Italian landscapes and the body itself

By Sam Moore

-

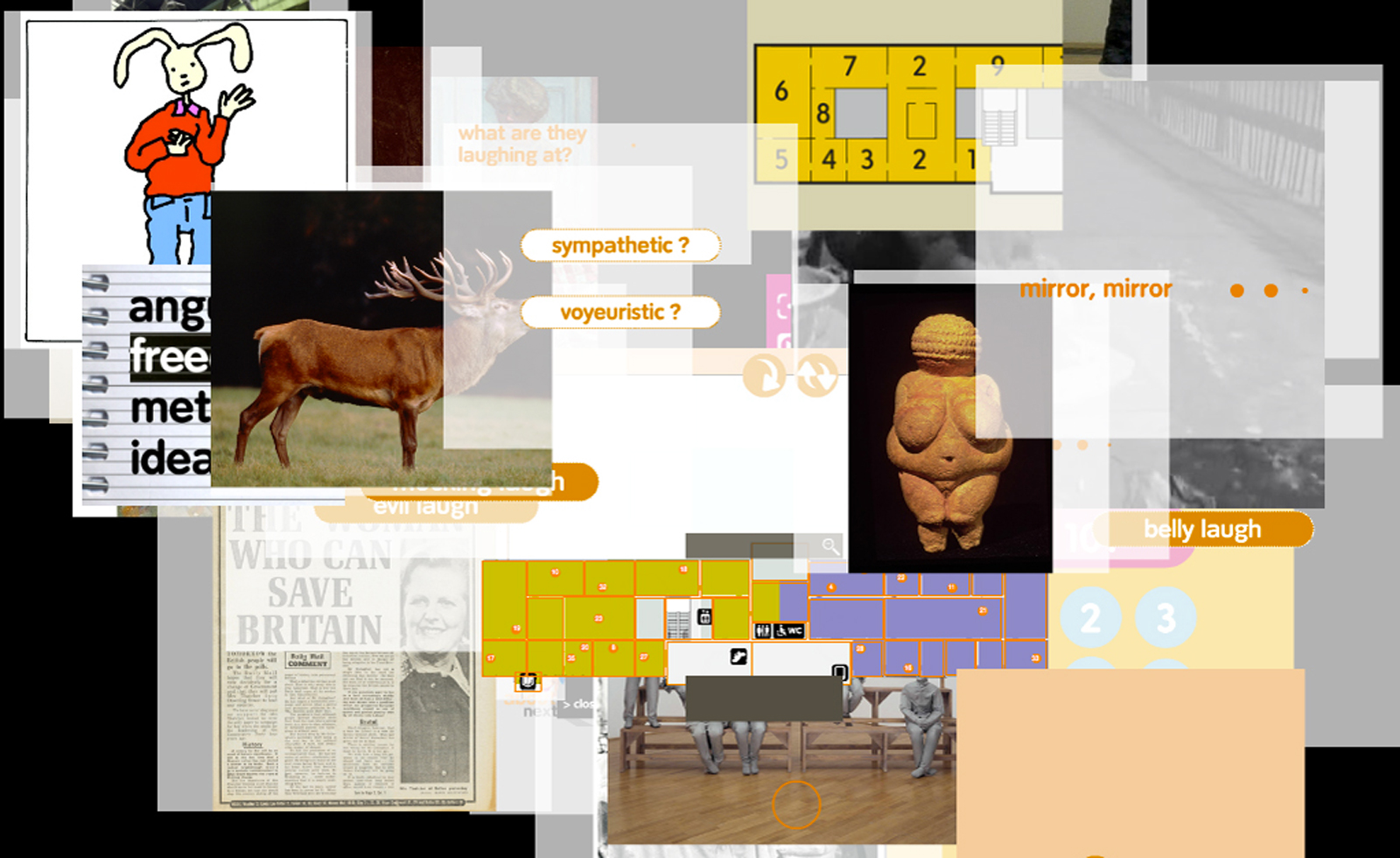

‘I just don't like eggs!’: Andrea Fraser unpacks the art market

‘I just don't like eggs!’: Andrea Fraser unpacks the art marketArtist Andrea Fraser’s retrospective ‘I just don't like eggs!’ at Fondazione Antonio dalle Nogare, Italy, explores what really makes the art market tick

By Sofia Hallström

-

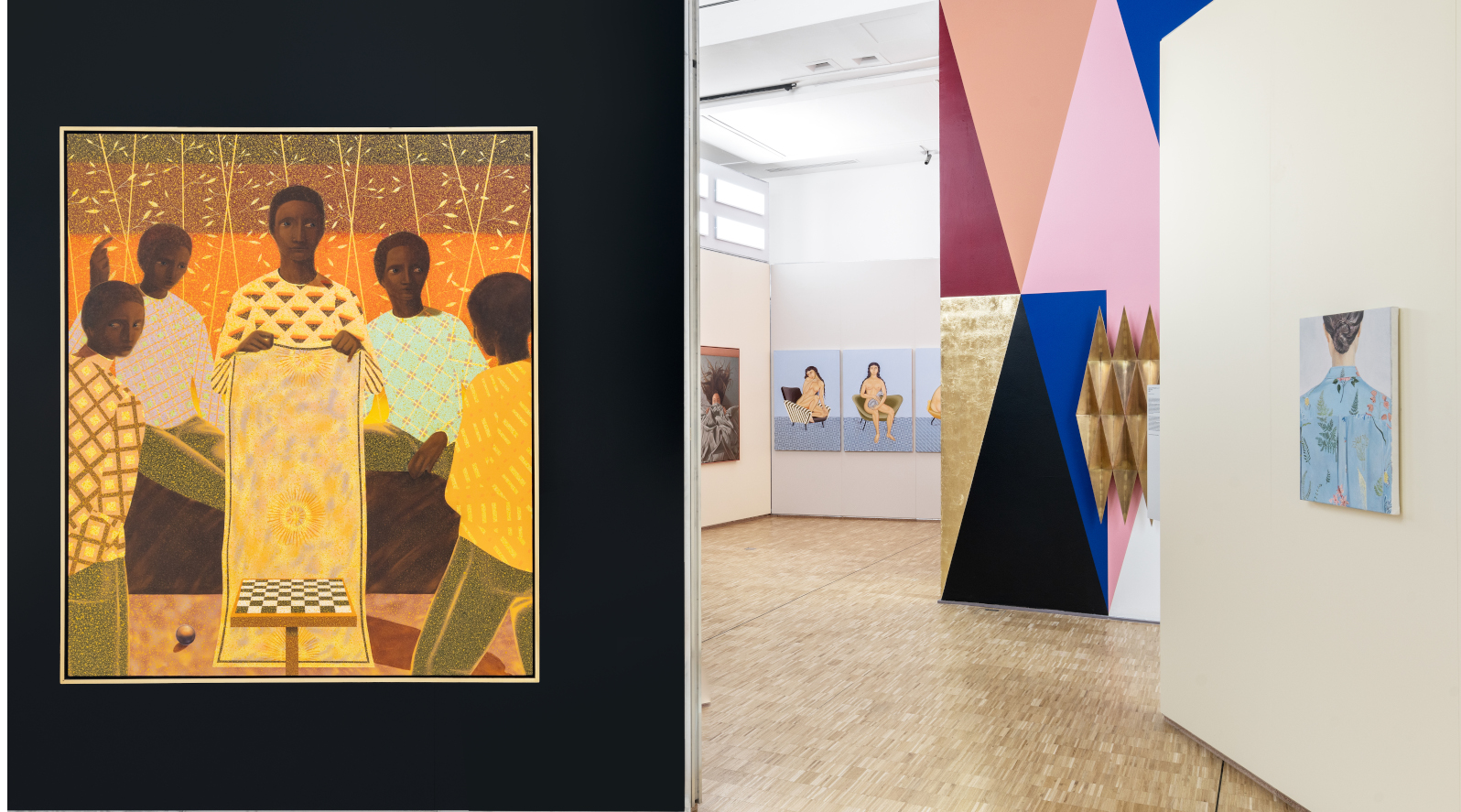

Triennale Milano exhibition spotlights contemporary Italian art

Triennale Milano exhibition spotlights contemporary Italian artThe latest Triennale Milano exhibition, ‘Italian Painting Today’, is a showcase of artworks from the last three years

By Tianna Williams

-

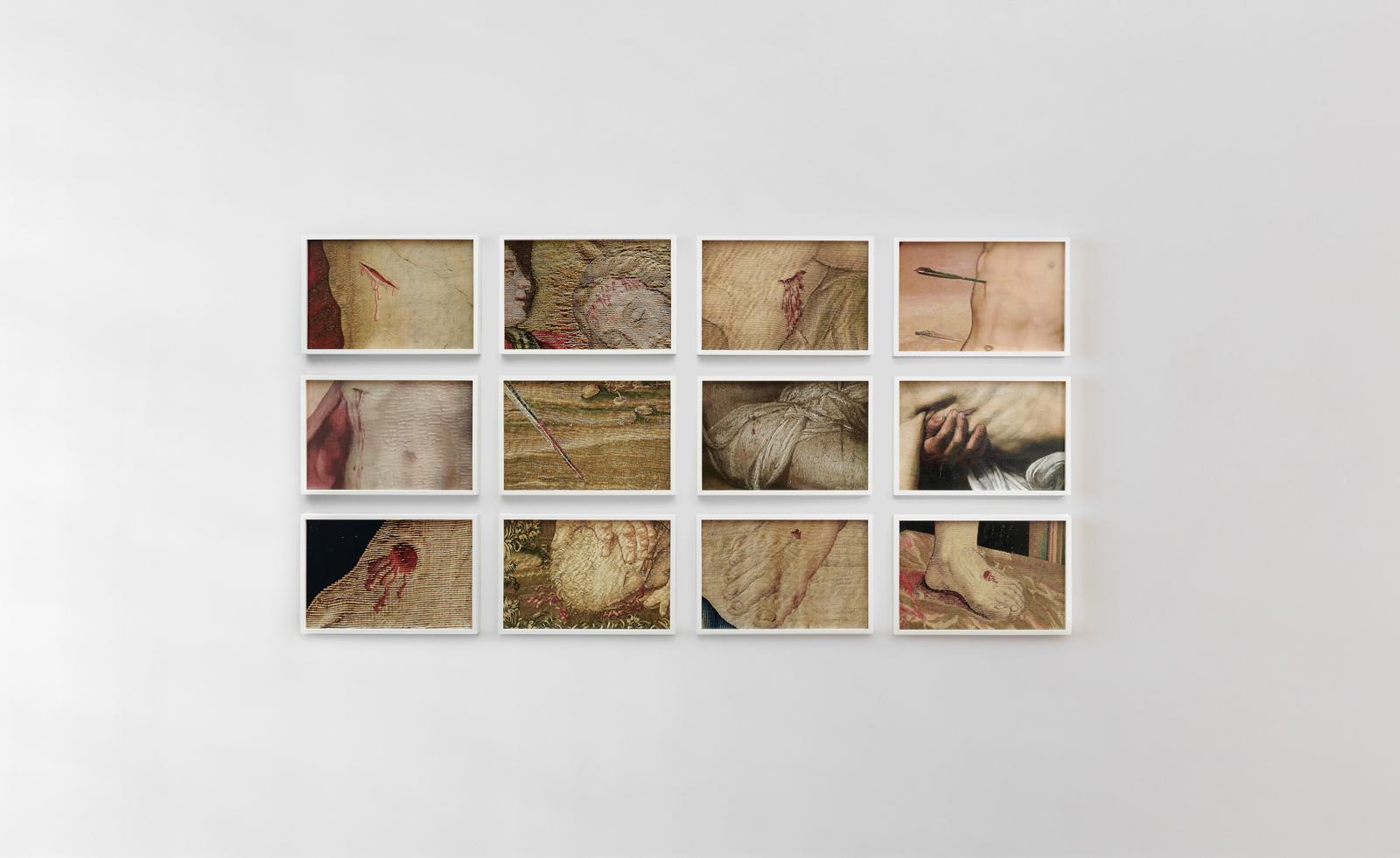

Walls, Windows and Blood: Catherine Opie in Naples

Walls, Windows and Blood: Catherine Opie in NaplesCatherine Opie's new exhibition ‘Walls, Windows and Blood’ is now on view at Thomas Dane Gallery, Naples

By Amah-Rose Abrams

-

Raffaele Salvoldi stacks hundreds of marble blocks for dazzling Milan installation

Raffaele Salvoldi stacks hundreds of marble blocks for dazzling Milan installationFor a Milan Design Week 2023 installation, Italian artist Raffaele Salvoldi teams up with marble brand Salvatori to create architectural sculptures comprising hundreds of marble blocks

By Harriet Lloyd-Smith

-

Remote Antarctica research base now houses a striking new art installation

Remote Antarctica research base now houses a striking new art installationIn Antarctica, Kyiv-based architecture studio Balbek Bureau has unveiled ‘Home. Memories’, a poignant art installation at the remote, penguin-inhabited Vernadsky Research Base

By Harriet Lloyd-Smith