From the ruins: how an industrial port became Japan’s sculpting centre

Yayoi Kusama’s giant yellow pumpkin on the beach of Naoshima Island, the fluid abstractions of Henry Moore in the foothills of Mount Fuji and the slender figures of Anthony Gormley in the forests of Kirishima. Such creations, set amidst some of Japan’s most beautiful landscapes, have become touchstones for travellers the world over who come to witness such ethereal, nebulous works of monumental art.

But where did it all start? Ube, a small, industrial city in Yamaguchi Prefecture, is barely known in the West. Here, amidst the ruins of post-war Japan, a group of little-known Japanese artists created the precursor and template of public sculpture in Japan.

Mukai Ryokichi, Ant Castle, 1962.

The city is now home to the Ube Biennale, the city’s bi-annual sculpture festival, which began almost 60 years ago in 1961, making it one of the world’s first contemporary sculpture festivals. Yet the belief in the value and purpose of public sculpture dates back even earlier, as the city rebuilt itself from the tragedies of the Second World War.

Throughout Japan’s Meiji Era of 1868 to 1912, Ube became a booming industrial city, built on coal, steel and heavy machinery. Even today, vapour billows from factories, tankers dock in the harbour and mine colliery dot the cityscape.

By the fated day of Pearl Harbor in December 1941, this peaceful city, with its bucolic, ancient landscapes, was one of Japan’s most prosperous economic powerhouses, a key infrastructure supplier to the rest of Japan.

The city is almost equidistant to Hiroshima in the east and Nagasaki to the west. It was an obvious strategic target for an American military looking to cripple Japan’s supply chain during the war. The city was extensively firebombed by American B-29s as part of a coordinated attack in the summer of 1945. ‘Two-thirds of the city was burnt to the ground,’ says Saito Ikuo, deputy director of Yamaguchi Prefectural Museum.

Shiga Masao, Let's smile together (Chairs of the rainbow color), 2019.

As Japan rebuilt, so Ube’s industry prospered again; but its citizens paid a price. Soot and dust rained down from the chimneys of the rebuilt factories. A record 56 tonnes of ash fell on Ube every day. It became known as Japan’s ‘polluted city.’

In the late 1950s, the city council launched a project titled ‘fill the city full of flowers.’ Flowers from across Japan were bought with the public purse. Sapling trees were planted in rows along Ube’s streets.

But then, in a moment of serendipity, a figure arrived from another era. In the mid-18th century, Étienne-Maurice Falconet, an impoverished sculptor from Paris, carved an egg-white marble sculpture of a young French woman, nude but for a bathing towel as she carefully dipped her toe into a pool of cool, dark water. The original, titled Bathing Girl, entered The Louvre in Paris in 1855. But a replica, cast in grey concrete, somehow found its way to post-war Ube. The concrete version of the sculpture was placed in the fountain by Ube’s central train station – known today as Ube-Shinkawa station.

‘This small sculpture caught our children’s attention,’ Rie Miura, the director of Ube Biennale, tells me. We’re standing before the concrete replica, now safely homed in Tokiwa Museum in Ube’s Towika Park. Rie Miura rests her hand on Bathing Girl’s head. The concrete sculpture is, at first glance, nothing much too look at. Her head is pockmarked and pitted with scratches and dents. Her grey skin has become discoloured by ash and decay. But she is historic and perhaps one of the most important sculptures in Japan. In her youth, she was a trailblazer.

Étienne-Maurice Falconet, Bathing Girl at Ube-Shinkawa station.

‘The children would gather together before her, and then sketch her,’ Rie Miura says. The young concrete woman poised above the fountain became a meeting place for people across the city. It gave the city’s leaders an idea, one founded in the Japanese belief in Kyodo Gikai – ‘of joint work for the public good.’

The Bathing Girl became the first of many such visitors. Over the next 60 years, and continuing today, more than 400 contemporary sculptures from around the world populated the cityscape of Ube.

First among these is Ant Castle, a steel-based tribute to Ube’s history by founding father of the Biennale, Mukai Ryokichi. The sculpture stands at the centre of Tokiwa Park; each edition of the Biennale is orientated around it. The artist is barely known in the West. At age 22, he was conscripted by the Japanese army and sent to Papua New Guinea to fight in the Battle of Rabaul during the Pacific War. After the war’s end, he travelled to Europe to spend a year developing his practice in Paris and in 1960, developed a new technique of casting aluminium alloys made in paraffin. He used this new technique to make Ant Castle, a complex, insect-inspired sculpture created with steel smelted in Ube’s factories. ‘It has become the symbol of Ube,’ says Daisuke Kihara, a senior figure at Ube City Hall.

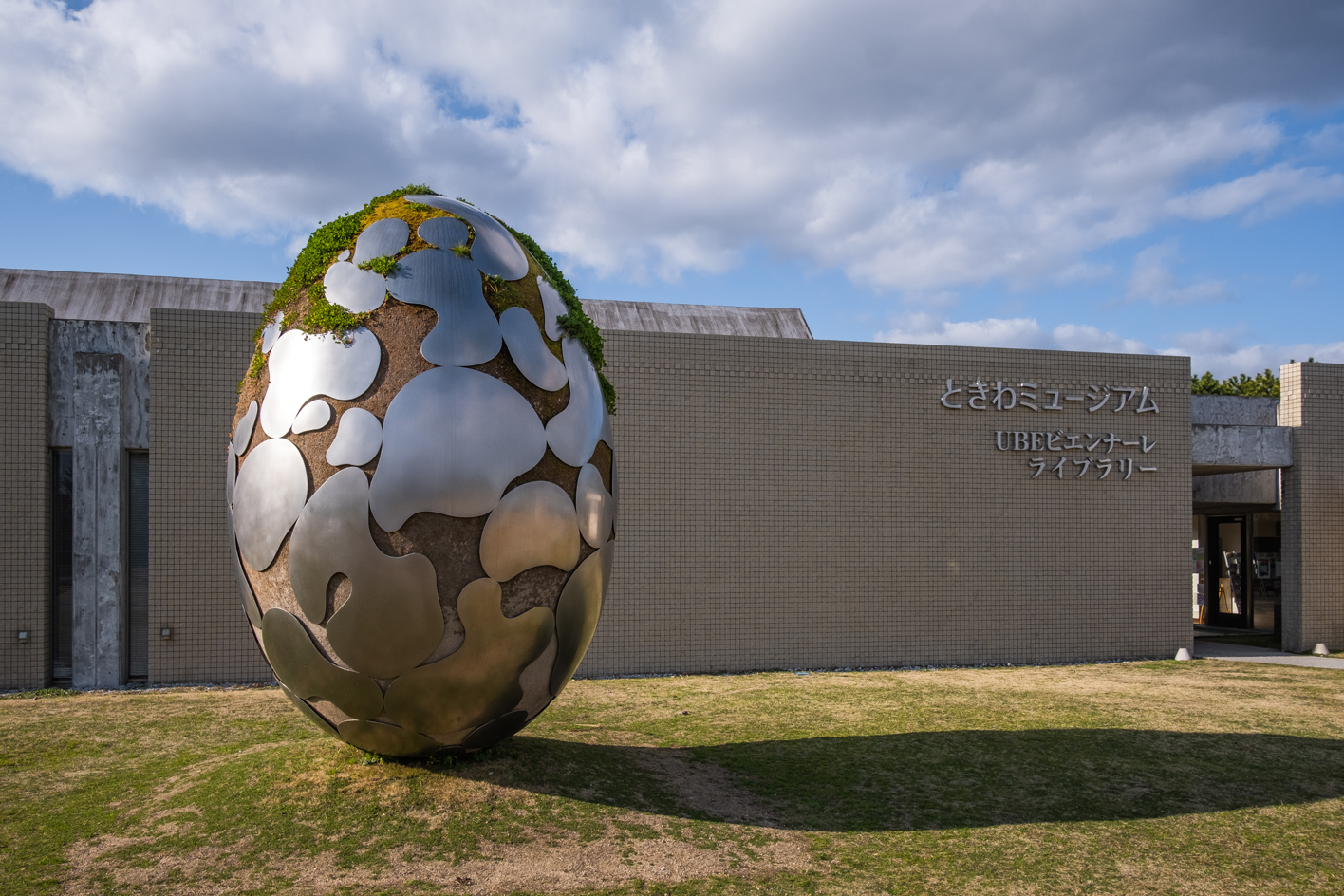

Miyake Shiko, The Birth of Life, 2019.

Alongside Mukai Ryokichi, artists Yoshitatsu Yanagihara, Churyo Sato and Yasutake Funakoshi began bringing sculpture to Ube. Yoshie Ueda, a central figure in the grassroots movement, remembers: ‘It was a pioneer spirit which brought citizens, artists and the city government together through social sculpture.’

In 1961, Ube held for the first time the City Outdoor Sculpture Exhibition. The Ube Biennale, as it became known, has been held every two years ever since. It has grown to become an international exhibition with entries from across Japan, the Far East and, indeed, the span of the world.

‘The competition is unique in that it isn't held to honour an artist nor is it to exhibit past works,’ Rie Miura says. ‘We are interested in what is new.’ The competition is a ‘level playing field’, which any artist, regardless of status or experience, can enter. ‘What we hope to honour is the skill and commitment to the work,’ Rie Miura says.

Wallpaper* Newsletter

Receive our daily digest of inspiration, escapism and design stories from around the world direct to your inbox.

Takeshi Hayashi, Standing Man, 2007.

The sculpture islands of Naoshima, Teshima and Inujima in the Seto Inland Sea are now world-famous tourist destinations, instantly recognisable from omnipresence on Instagram. Also more famed is the Hakone Open Air Museum, which opened in 1969 close to Mount Fuji, the Noguchi-designed Moerenuma Park in Hokkaido, the northernmost island of the country, and the Kirishima Open Air Museum in Kagoshima, on the southern-most island of Kyushu. Ube was the inspiration for each.

Wandering through the city, it is possible to read in the many sculptures here more than half a century of turbulent post-war history, conjoined with the civic values and defiant character of the city, all expressed through abstract sculpture.

Like the humble concrete girl dipping her toe into unknown waters, each of Ube’s sculptures speaks of art’s ability to help us embrace the future, whatever might lie in wait.

INFORMATION

Ube Biennale 2020, until 30 November. ubebiennale.com

Tom Seymour is an award-winning journalist, lecturer, strategist and curator. Before pursuing his freelance career, he was Senior Editor for CHANEL Arts & Culture. He has also worked at The Art Newspaper, University of the Arts London and the British Journal of Photography and i-D. He has published in print for The Guardian, The Observer, The New York Times, The Financial Times and Telegraph among others. He won Writer of the Year in 2020 and Specialist Writer of the Year in 2019 and 2021 at the PPA Awards for his work with The Royal Photographic Society. In 2017, Tom worked with Sian Davey to co-create Together, an amalgam of photography and writing which exhibited at London’s National Portrait Gallery.

-

The Viceroy seaglider is a proposed new electric passenger craft to skim the waves at speed

The Viceroy seaglider is a proposed new electric passenger craft to skim the waves at speedElectric propulsion finds a new outlet in Regent’s Viceroy seaglider, a coastal transporter that uses wing-in-ground effect to achieve its startling speed

-

A new photo book and exhibition capture an intimate journey through Peru

A new photo book and exhibition capture an intimate journey through PeruAt Photo London, an exhibition and limited edition Belmond book capture the beauty of Peru via the Andean Express, taken on film

-

Timeless yet daring, this Marylebone penthouse 'floats' on top of a grand London building

Timeless yet daring, this Marylebone penthouse 'floats' on top of a grand London buildingA Marylebone penthouse near Regent’s Park by design studio Wendover is transformed into a light-filled family home