En pointe: 10 years at the Royal Ballet and Wayne McGregor is still dancing to a different tune

In his ten years as the Royal Ballet's resident choreographer, Wayne McGregor has faced the wrath of the most pointy-tongued of audience members. Dancers – particularly ex-dancers – are a bitter bunch, and we pick up on every mis-step, delighting at the drama of a heavy landing. We're like this at the best of times, let alone when viewing a performance so groundbreaking that it alters the DNA of the dance form we have devoted our childhoods to perfecting. Perhaps this is why McGregor's performances garner such strong opinions. Or perhaps it is because audiences, filled with dancers or otherwise, are resistant to something truly revolutionary. Despite a spattering of negativity, and the odd lukewarm curtain call, McGregor has made a name for himself, deservedly, as the most original choreographer of our age.

Olivia Cowley rehearses 'Multiverse' with Wayne McGregor.

He has been described as the king of adaption, a master of surprise and the busiest man in dance. He describes himself more simply, as 'present tense'. Mr Mono-track. Someone who lives in the moment. This single minded approach has been a source of criticism directed at McGregor. There's too many recurring themes in his work. He doesn't evolve enough, apparently. This critique is rarely leveled at artists working in different disciplines. 'No one would question Antony Gormley for producing multiple iterations of his sculptural forms,' McGregor writes in the programme of his anniversary, three-part performance at the Royal Opera House. 'Every artist has preoccupations, themes that they return to again and again. It's interesting in dance that these signatures are often criticised, and that artists seem required to forever change who they are.'

Multiverse, 2016, made its world debut at the Royal Opera House last week. Pictured, dancers Matthew Ball and Marianela Nuñez.

In conversation with Wallpaper*, McGregor owns his trademark movements proudly. 'I think, partly, my ten years at the Royal Ballet have been unified by one focused approach and message. I do have a physical signature, but the dancers I've been working with over the years have developed within this framework, and my physical signature has now become theirs.' The likes of celebrated Royal Ballet principles Edward Watson, Sarah Lamb and Akane Takada spring to mind.

This symbiotic relationship between dancer and choreographer is part of McGregor's criticism-busting appeal. His continual praise and respect of the talented practitioners he works with helps to breed longstanding, working friendships – sparking moments of jointly-constructed genius. By all accounts, he's a joy to work with. 'To strike a balance between each of the different aspects of a production – the music, design, technology, dance – you have to get great team members,' McGregor explains. 'I'm a fan, first and foremost, of everyone I collaborate with. You have to trust them with space and freedom. I think this is what my collaborators are all interested in as well – they want to be challenged.'

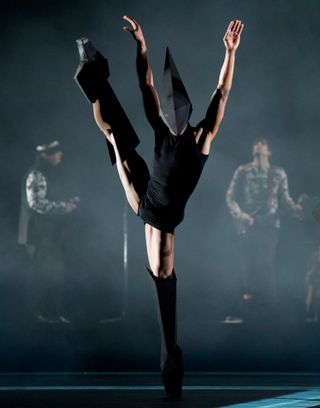

McGregor's creative collaborations have spanned several disciplines. Above, fashion designer Gareth Pugh's costume design for Gareth Pugh

This being said, another questioning glance shot McGregor's way over the years has concerned the music's apparent disconnect to the choreography. Some say the music is like a film-score warbling away as the background to a cast of actors. But, as Studio Wayne McGregor's Polyphonic Playground proved earlier this year, the dancers and the music are intimately connected in McGregor's mind – just in a way we've never been seen before. In this instance, the dancers use their bodies to literally play the music, moving across and over an interactive, synthesised climbing frame.

More generally, instead of choreographing his dancers to move in time to the music, it seems McGregor just asks them to feel it. This connection, arguably more intimate than any perfectly timed port de bra is also seen in Carbon Life, first performed in 2014, and again as part of the anniversary special. Directed by Mark Ronson, contemporary musicians mingle among the dancers. Most notably, 'Dave' the rapper, whose rhythmic speaking is near impossible to dance to – yet somehow McGregor makes it work. The feeling is right, even if the timing isn't. And who cares anyway, because there's a rapper on stage, dodging the high kicks of a prima ballerina. 'The idea that "movement should describe the music" is limiting,' McGregor says of this performance. 'You have to ask: what are the landscapes that the music provides; what's the architecture of the music?'

Sarah Lamb in 'Chroma', 2013.

The renowned set designers McGregor works with enjoy a similar level of creative challenge. In Chroma, the performance that bagged McGregor his resident choreographer role back in 2006, John Pawson was given free range to stamp his minimalist mark on the stage. A blank white canvas is punctuated by a flat screen of light, bathing the stage and theatre in a subtly shifting spectrum of blues, greens and greys. This clean minimalism influenced McGregor's choreographic aesethetic. In each of Chroma's many movements, nothing is wasted. Each step is essential, charged with meaning and beautifully poised. These facets have always been the backbone of ballet – McGregor just paired them with a designer who felt similarly. McGregor consulted Pawson's Minimum manifesto, which describes the perfectly minimal object as 'when every component, every detail, and every junction has been reduced or condensed to the essentials'. In this sense, the set and the choreography are moving together, in economical harmony.

There was an air of impossible cool around Chroma that McGregor has somehow managed to maintain for the last decade, aided by his stylish use of the day's technology trends. Notably, in the 2008 production of Infra, where artist Julian Opie's cartoon walking figures strolled in a stream across a stage-wide LED screen. Techno-spectacle ensued again in McGregor's 2014 collaboration with artist Tauba Auerbach, who blazoned the back wall with a series of illuminated geometric glyphs, creating the aura of a contemporary basement bar in the austere Opera House.

Technological stage settings are crucial to McGregor's new performance, Multiverse – his 15th work for the Royal Ballet. American composer Steve Reich penned a new piece for the occasion, Runner, an intense, 16 minute composition for strings, piano, wind and percussion, with no breaks or pauses. It's a challenge the dancers took on with aplomb, set to a backdrop of photographs of the migrant crisis that eventually pixelated into a giant tableau of a classical war painting. With the hyper-extented dancers twisting on stage, the scene was fiercely moving.

A scene from 'Woolf Works', staged last year at the Royal Opera House, showcases McGregor's penchant for simple yet powerful set spectacles.

McGregor is an unconventional choreographer in almost every sense, so it's fitting that he didn't have a conventional path into the profession. Most choreographers go through formal dance training themselves – but for McGregor, 'choreography and the world of dance kind of crept up on me – I was born in the 1970s among the John Travolta movies, the Saturday Night Fevers. And I loved them. I wanted to come in at a creative level quite early. It doesn't matter where you start, but how creative you can be with it.' After witnessing the remarkable rise of McGregor, we're inclined to agree. But in the artist's own opinion, it's only just beginning. 'I'd love for the goalposts to move even further,' he explains. 'Ballet should be in constant change and flux. There's no limits as to what it can, or should, do.'

If the last ten years are anything to go by, we predict the next decade will see McGregor making increasingly bold use of technology, and the possibilities it offers dance. Bigger sets, bigger sound, more sass and sex. But this is the king of adaptation – the master of surprise – we're discussing, so we're not placing any bets.

Steven McRae, Marianela Nuñez, Federico Bonelli and Francesca Hayward performing Multiverse, which featured a striking set design by Pakistani artist Rashid Rana. © Royal Opera House

The ballet was shown as part of a triple bill, which included 2013’s Carbon Life. © Royal Opera House

Also part of the bill was Chroma (pictured, Edward Watson and Olivia Cowley at the 2013 performance). The set was designed by architect John Pawson. © Royal Opera House

Chroma, performed in 2016 by Lauren Cuthbertson, Steven McRae and Rachael McLare. © Royal Opera House

INFORMATION

Wallpaper* Newsletter

Receive our daily digest of inspiration, escapism and design stories from around the world direct to your inbox.

For more information, visit the Royal Opera House website

Elly Parsons is the Digital Editor of Wallpaper*, where she oversees Wallpaper.com and its social platforms. She has been with the brand since 2015 in various roles, spending time as digital writer – specialising in art, technology and contemporary culture – and as deputy digital editor. She was shortlisted for a PPA Award in 2017, has written extensively for many publications, and has contributed to three books. She is a guest lecturer in digital journalism at Goldsmiths University, London, where she also holds a masters degree in creative writing. Now, her main areas of expertise include content strategy, audience engagement, and social media.

-

Unlike the gloriously grotesque imagery in his films, Yorgos Lanthimos’ photographs are quietly beautiful

Unlike the gloriously grotesque imagery in his films, Yorgos Lanthimos’ photographs are quietly beautifulAn exhibition at Webber Gallery in Los Angeles presents Yorgos Lanthimos’ photography

By Katie Tobin Published

-

Remembering architect David M Childs (1941-2025) and his New York skyline legacy

Remembering architect David M Childs (1941-2025) and his New York skyline legacyDavid M Childs, a former chairman of architectural powerhouse SOM, has passed away. We celebrate his professional achievements

By Jonathan Bell Published

-

At the Institute of Indology, a humble new addition makes all the difference

At the Institute of Indology, a humble new addition makes all the differenceContinuing the late Balkrishna V Doshi’s legacy, Sangath studio design a new take on the toilet in Gujarat

By Ellie Stathaki Published

-

Year in review: top 10 art and culture interviews of 2024, as selected by Wallpaper’s Hannah Silver

Year in review: top 10 art and culture interviews of 2024, as selected by Wallpaper’s Hannah SilverFrom Antony Gormley to St. Vincent and Mickalene Thomas – art & culture editor Hannah Silver looks back on the creatives we've most enjoyed catching up with during 2024

By Hannah Silver Published

-

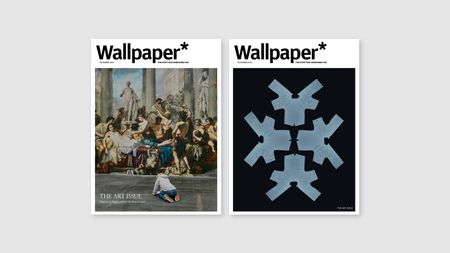

Discover Wallpaper* November 2024: The Art Issue

Discover Wallpaper* November 2024: The Art IssueThe art special is on sale now. Confront the classical canon with Elmgreen & Dragset, get down with LoveFrom x Moncler, and wear art on your sleeve with Christiane Kubrick x JW Anderson

By Bill Prince Published

-

Wayne McGregor’s new work merges genetic code, AI and choreography

Wayne McGregor’s new work merges genetic code, AI and choreographyCompany Wayne McGregor has collaborated with Google Arts & Culture Lab on a series of works, ‘Autobiography (v95 and v96)’, at Sadler’s Wells (12 – 13 March 2024)

By Rachael Moloney Published

-

John Pawson unveils first-ever sculpture in Tokyo exhibition

John Pawson unveils first-ever sculpture in Tokyo exhibitionAt The Mass, Tokyo, British architect John Pawson stages his first solo exhibition in Japan, revealing his first sculpture and a new photography series

By Harriet Lloyd-Smith Published

-

Vanessa Beecroft’s ethereal performance and sculpture exhibition explore Sicily’s cultural history

Vanessa Beecroft’s ethereal performance and sculpture exhibition explore Sicily’s cultural historyAt the historic Palazzo Abatellis, Sicily, Vanessa Beecroft has unveiled ‘VB94’, a new tableau vivant comprising a one-time performance and a new series of sculptures, the latter on view until 8 January

By Hili Perlson Published

-

Subversive artist Cosey Fanni Tutti on individuality and annihilating limitations

Subversive artist Cosey Fanni Tutti on individuality and annihilating limitationsFollowing the launch of her new book Re-Sisters, we speak to Cosey Fanni Tutti about conquering fear through action, stepping into the unknown, and the secret to making art that matters

By Mary Cleary Last updated

-

Can the Marina Abramović Method change your life?

Can the Marina Abramović Method change your life?Lady Gaga and Jay-Z are among those who have followed the Abramović Method to reach higher creative consciousness. Now, the artist’s iconic approach has been translated into a series of instruction cards for all. If you don’t try, you’ll never know

By Harriet Lloyd Smith Last updated

-

Ragnar Kjartansson’s dramatic soap opera inaugurates GES-2 in Moscow

Ragnar Kjartansson’s dramatic soap opera inaugurates GES-2 in MoscowIcelandic artist Ragnar Kjartansson inaugurates the much-anticipated V-A-C Foundation’s GES-2 House of Culture in Moscow. Santa Barbara – A Living Sculpture is a bold, theatrical work that examines the relationship between Russia and the US

By Amah-Rose Abrams Last updated