William Wegman: a profile

A video art pioneer and conceptual photographer, we retrace Guest Editor William Wegman's career and celebrate his four-legged sitters

A chance encounter with a piece of salami, sometime in 1970, changed the course of William Wegman's career. The photographer – who at the time described himself as a minimalist-conceptualist trapped in a 'tough corner' artistically – had drawn circles on his hand to mimic the stones of his ring. Then later that day, at a party, he noticed the similarity between the circles on his hand and the circles of pepper in a piece of salami. He rushed out to buy some salami and set up a picture, creating Cotto (1970). He now had his reason and his clarity, his beginnings and his endings; all to be explored in the form of the set-up picture and the found object. The photograph or the film would now be the work, not a document of the work.

Wegman was born in Massachusetts in 1943. He was 'Bill the Painter' at high school and completed his undergrad studies at the Massachusetts College of Art. There, he focused on abstract painting in what he has described as an 'overbearing, serious way' – 'manifesto' art movements such as Dadaism and constructivism were a major influence. A student at the University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign in the 1960s, he met the filmmaker Ronald Nameth, with whom he would later show films at Warhol's Electric Circus in New York. Wegman's first photographs and films were a way of capturing the ephemeral works – mostly inflatable structures and kinetic sculptures – he was making.

After graduation in 1967, Wegman spent three years experimenting with the first in a long line of 'found' objects, particularly mesh and other fabrics. Furniture also made an appearance, as did inexpensive materials, such as shoes, pots and pans. In one performance piece he threw radios off a roof; in another he floated Styrofoam commas down the Milwaukee River. It was one of these late 1960s works, the 'screen pieces' fabric installations, that was shown at the seminal exhibition 'Live in Your Head: When Attitudes Become Form', at the Bern Kunsthalle in March 1969, alongside works by Richard Serra, Joseph Beuys and Richard Tuttle. The following year, Wegman moved to California to take up a teaching post at Long Beach. His first West Coast pictures focus on difference and duality. His diptych Light Off/Light On (1970) are identical images of door and wall, a flipped switch marking one from the other. In Big and Little (1971) Wegman poses with a student bearing a remarkable likeness to him. Both are draped in a series of garden implements, but as the student is bigger than the artist, so all his tools are bigger than the artist's. 'It's an appropriate rendering of the facts,' says Peter MacGill, a New York gallerist who has worked with Wegman for decades. 'But it is filtered through Bill's incredibly intelligent humorous filter.'

'Wegman started working in California as a conceptual artist,' says Marc Selwyn, Wegman's LA gallerist, 'and was associated with John Baldessari and Allen Ruppersberg, Bruce Nauman and Ed Ruscha, the whole group of them exchanging ideas and doing really radical things. Before this, photographers in California were people like Ansel Adams, who made beautifully crafted, well-composed photographs. And then comes a group of artists who've decided that what's important is the idea, and the documentation of a performance. This was very typical of the time; there was a rebellion against traditional ideas about what an art object was.'

In hindsight, the move to California in 1970 brought one other major development: Wegman and his then wife Gayle bought a puppy, a Weimaraner they named Man Ray and who was destined to become his most important 'found' object. 'He was "found" I guess,' says Wegman. 'I didn't expect to be working with him, but as a young puppy he came to my studio and convinced me that it was something we should be doing together. He was always there anyway. I had dogs growing up, but I had never had a Weimaraner, and they really require a lot of attention – so that just sort of happened.'

Turning the camera on Man Ray made the dog happy. And he was just there, a fixture in the studio, like the props and food and chairs that pepper Wegman's images and videos at this time. Life, in all its droll banality, was Wegman's subject. His own body is sometimes the canvas – particularly in his early videos, such as Stomach Song (1970), where Wegman sits, bare-chested, and hums a tune, his torso resembling a face, his nipples as eyes, bellybutton as mouth. Other films have Man Ray dragging a microphone around or lapping up milk dribbling from Wegman's mouth.

'He was a pioneering video artist,' says Fredericka Hunter, co-owner of Houston's Texas Gallery, who has known Wegman since 1973. 'He was the one who saved us from the absolute boredom of early video art. There were some insane ones and some that bordered on pornography, but for the most part, oh the boredom. I always think of Bill as the pioneer who saved us.'

If his photographs were ironic and quirky, Wegman's video art explored incongruity to deliver humour to an even greater degree. In Spelling Lesson (1973–74), he explains to Man Ray that while the dog had spelled 'out' and 'park' correctly, he had spelled 'beach', with two 'e's. In Two Dogs (1975–76), Man Ray and a companion track an unseen tennis ball, their synchronised ballet of heads providing the delight. Despite their low-tech production values and limited action, some of the videos could easily have been lifted from a sketch show, and indeed Wegman did show Spelling Lesson and Two Dogs when he first appeared on Late Night with David Letterman in 1982 – an appearance that would be the first of many, and one of the first signs of his widening appeal.

'He prefigures in his videos what digital technology has enabled people to do and which now fills YouTube,' says MacGill. 'And some of his photographs prefigure his videos. In Family Combinations (1972), he blends pictures of his mother and father and of himself, so he was making these composite portraits long before Photoshop made it possible for everyone.'

In 1972, Wegman left California for New York, where he continued to work in video and photography, using objects found in dumpsters around the city, but also began to draw. Often text-based, these drawings explore lists, cursive handwriting and typography. He says it was a relief not to have to drag things in front of a camera, just to use pencil and paper. Meanwhile, also in 1973, Wegman videos featured in the Whitney Biennial – the first time video art was included.

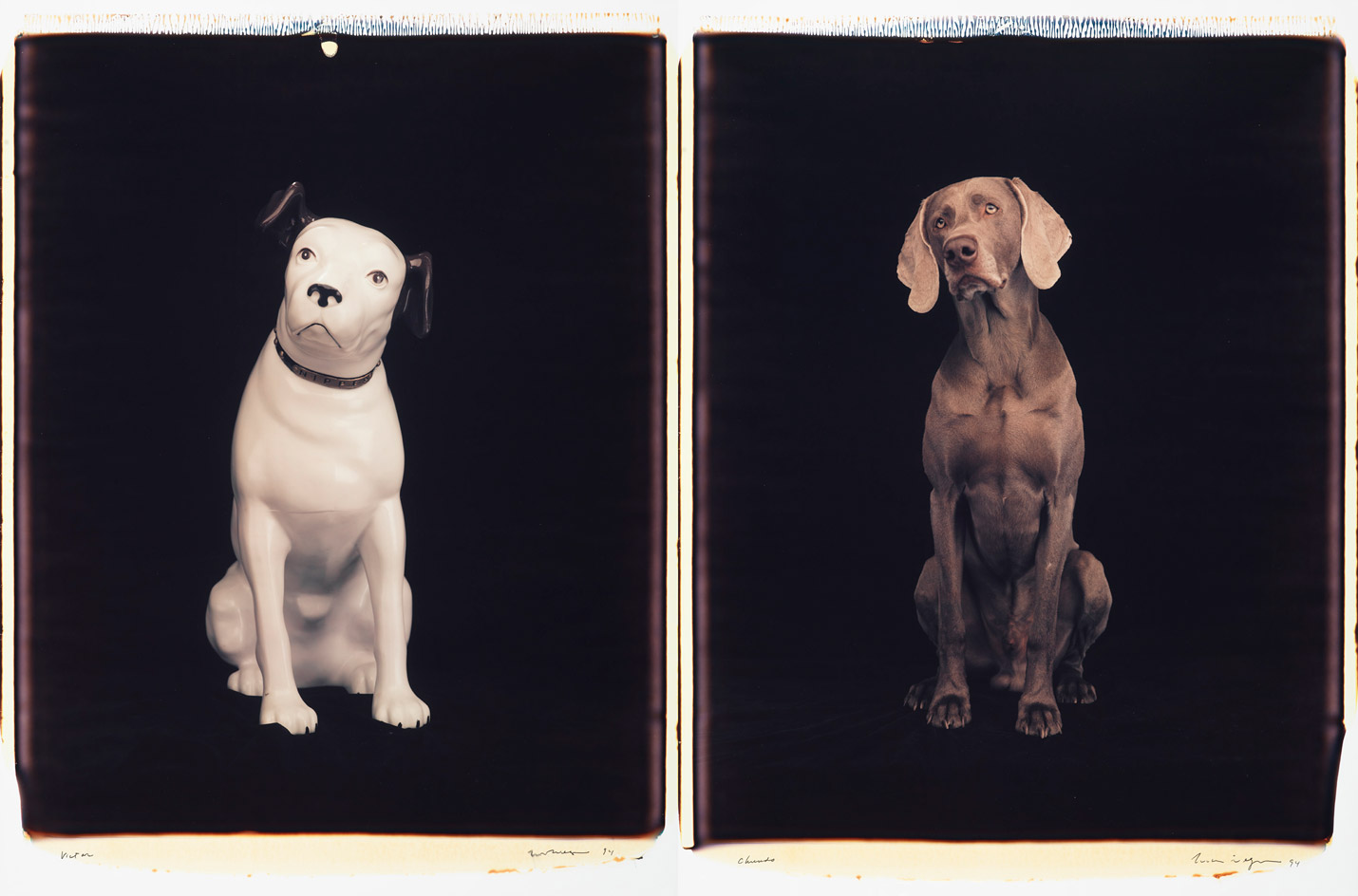

Yet in 1978 Wegman broke with video art, partly because of changing technology. Colour photography required hotter lights, a more professional studio set-up which affected his relationship with the dogs. At around the same time, Polaroid made a 20x24 camera to promote its new Polacolor II Film. It was a monster, weighing 107kg, but contained a roll of modern instant film and produced richly coloured, large-format photographs. Artists and photographers, Wegman among them, were invited to the company's HQ to see how they might use the camera. Wegman's first images in this new medium adhered to his black-and-white manifesto and so he shot his grey dog against a black background. A second, now highly collectable, image was shot with just a hint of colour: nail varnish on the dog's claws and in a bottle in the foreground. It was titled Fey Ray, a typically Wegman pun on a made-up male and the 1930s actress.

But the richness and beauty of the medium could not be ignored, says Wegman. Nor the immediacy and unpredictability of the instant film. 'When I started to use the Polaroid camera, I couldn't really plan for it. I used to make little sketches for my photographs in the 1970s but with the Polaroids all kinds of different things would happen. And that's the brilliance of photography: you get something that is better than you almost. The lucky accident happens over and over again if you just spend time at it. And that really changed what I liked to think of as my manifesto; in a way it corrupted it.

'Before I worked with Polaroid I was interested in only making works that would be the same reproduced in books or on TV. It was a sort of anti-picture quality, the opposite of the Zone System, which all those that studied photography – which I didn't – would embed in their process. But with me coming to it quite late, and having an aversion to photography, I tried to not get involved with that. Then with the Polaroid some of the pictures were just incredibly beautiful and I just had to accept it and go with what happened.'

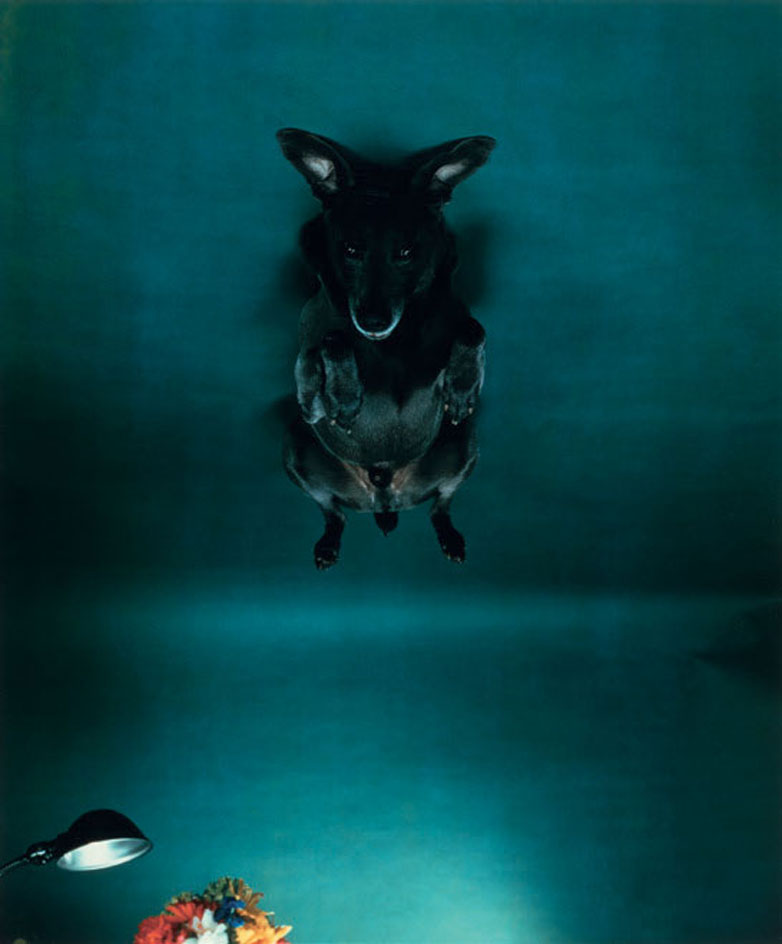

And what happened was lush, textured images of immense richness. Much may have remained the same: Wegman started with an idea, a dog, and a prop. But the outcomes were stunning photographs that could have come from a colour-fixated Yousuf Karsh, with the formality of the composition undercut because the sitter is a dog, not a Churchill or a Hemingway. The work is serene and often surreal. Man Ray became both subject and supporting object; he was fixed with a sock trunk in Elephant (1979) or made to float from the ceiling in Ray Bat (1980).

Wegman's increasing recognition and popularity included not just appearances on late night TV, but also an acclaimed book, Man's Best Friend, which The New York Review of Books described as the most original photography book since Robert Frank's The Americans. When Man Ray died of cancer in March 1982, The Village Voice put him on its cover as 'Man of the Year'.

Following Man Ray's death, Wegman worked without a dog for five years, photographing paired people and objects in his studio. He also took up painting for the first time in 15 years, much influenced by the landscapes and feelings generated by spending more of his time in the Rangeley Lakes area of Maine. Among these paintings were a number that feature architectural icons, from Buckminster Fuller's domes, to Wright's Fallingwater, or Le Corbusier's chapel at Ronchamp. His landscape and architectural interests reappear in more recent paintings, based on Wegman's huge collection of postcards.

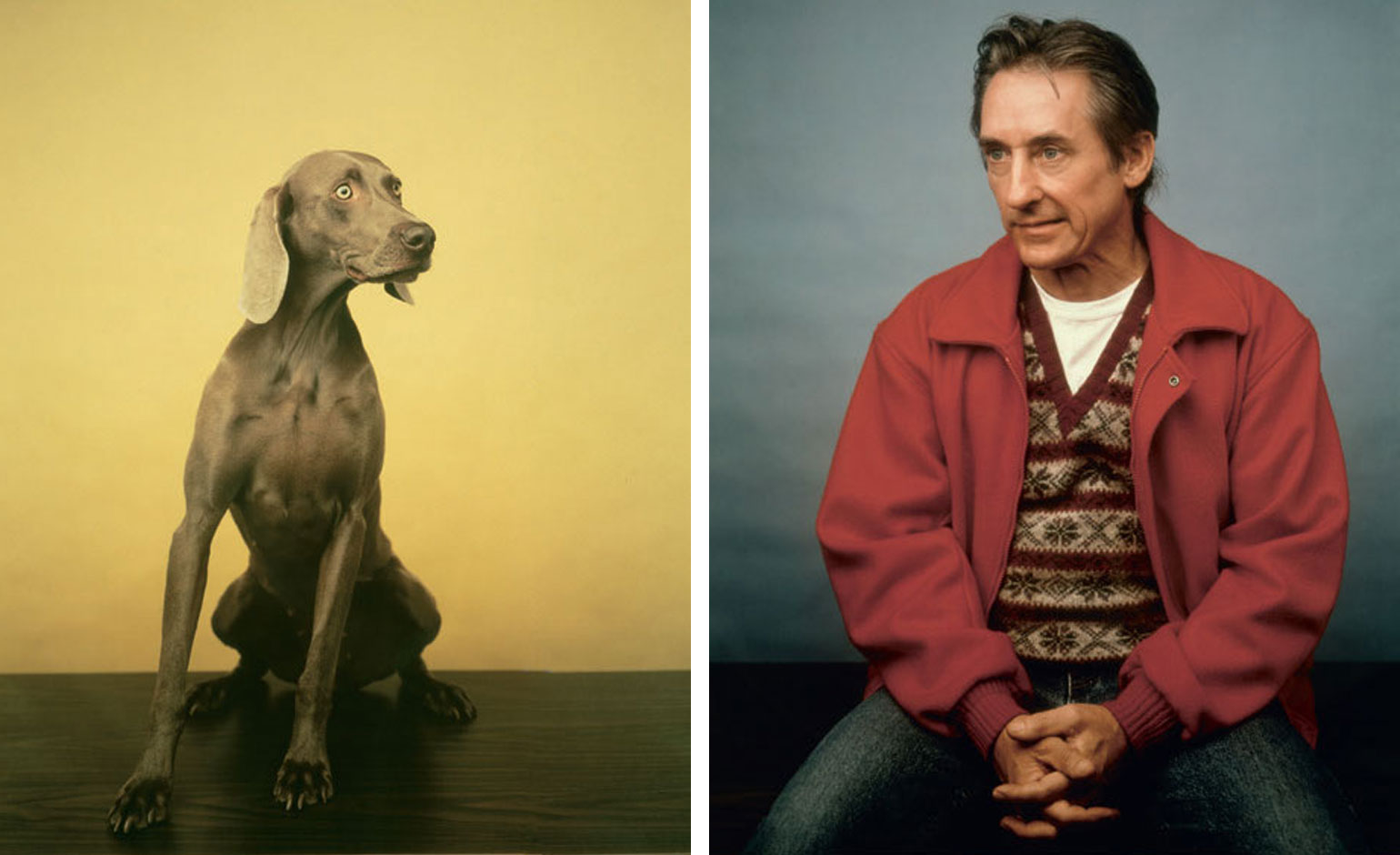

Wegman returned to photographing dogs in 1987, making his new dog Fay Ray the focus of images that included, that year, a diptych of dog and artist called Fay/Ruscha (1987), now one of a large collection of Wegman works owned by New York's MoMa. Fay lent a new, sometimes disturbing, psychological element to the photographs, able to be dressed as Wonder Woman, or draped in a Bauhaus chair for Lolita (1990). He faced anthropomorphism head on in 1997 with a work titled 2 Dogs. Dressed up to Look Like Children, which featured a found photograph of two actual children. By then Fay Ray had become a fixture of Sesame Street, heralding the children's books and calendars that would come to fix Wegman in the popular imagination. Today Wegman is onto a new generation of dogs, sometimes shot in studios, sometimes in the Maine woods, or on pedestals and, most recently, on classic furniture.

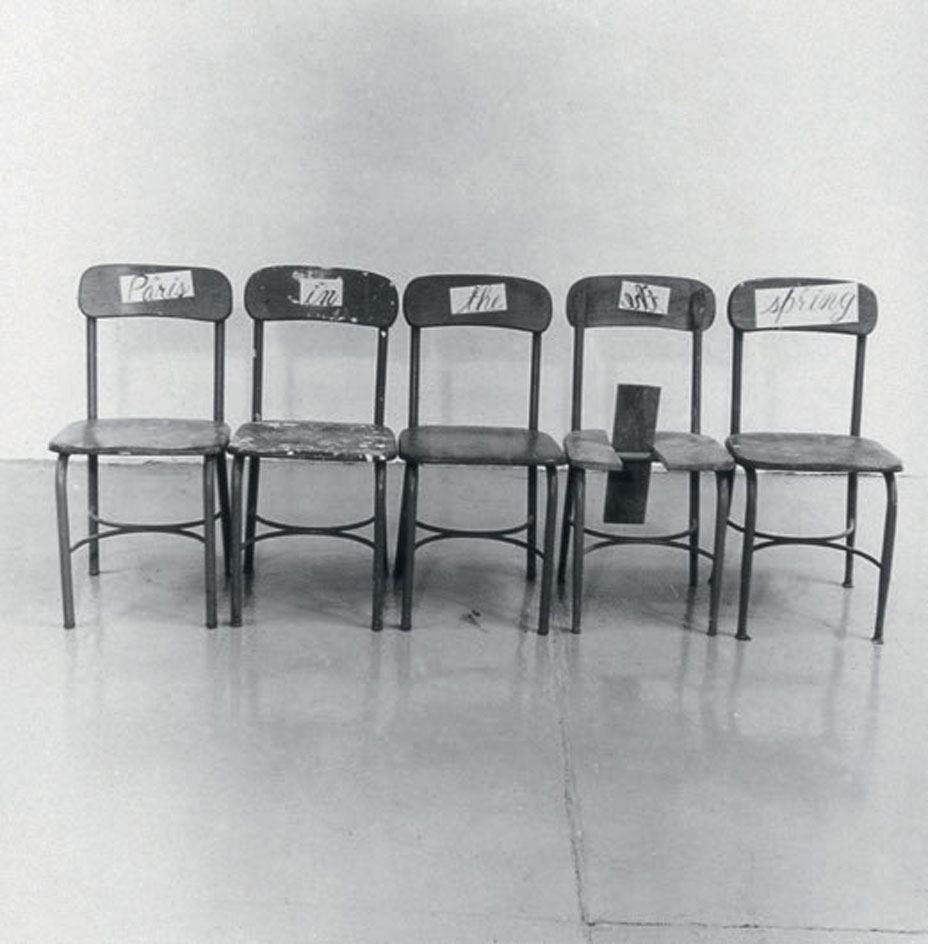

Furniture has featured in Wegman's photography since the start, but rarely the midcentury classics. Instead he took three ordinary chairs and pinned cards with the words 'The', 'Barcelona' and 'Chair' to their backs (The Barcelona Chair, 1971). 'Back in the 1970s,' says Wegman, 'I liked playing with really everyday, really droll material. Very rarely did I use art references, but the Barcelona chair somehow crept in.' His latest work features Eames, Nakashima and Herman Miller classics thanks to the intervention of his wife Christine, who was tired of seeing the same pedestals again and again: 'She said, "You're not going to use that awful thing again, why don't you find something more interesting?" and arranged for the furniture to be brought in.

'I'm like a stand-up comic who takes suggestions from the audience. If somebody comes in with a bulldog and some other prop, I'll find something to do with it. So I went to the studio in New York and picked out things I thought might be good to interact with my two amazing dogs, and we set to work. I'm working with a digital camera now, which is like the Polaroid in that you get pretty much instant feedback.' In a new portfolio of images shot just for Wallpaper* as the centrepiece of his guest editorship, Wegman perched Topper and Flo on contemporary American furniture he considered most complementary to his sleek hounds. Our US editor Michael Reynolds, who helped Wegman choose the key pieces, was given an unprecedented glimpse at the reality behind the serenity of so many Wegman images. Our exclusive shoot captured the two canine models, teeth bared and play fighting, before making up. It's rare ever to see a Wegman dog even with its mouth open.

'Bill's ideas are oblique,' says Fredericka Hunter of Texas Gallery, which showed the exhibition 'Good Dogs on Nice Furniture' this summer. 'There isn't a straight line of idea development, it is about the Dada. About letting it go haywire. But these dogs sit up straight; that's how Weimaraners sit. And the pictures are so luscious, so smart. The intensity of the colour, the compositions are really something.' Wegman himself is very practical about why his dogs ended up on furniture: 'The dogs had to be brought up to the 20x24 camera level. It was a refrigerator-sized beast; you couldn't point it down at something, you had to bring anything that you were photographing up to its level.'

What links all these works, beyond the humour, is the element of performance. 'Putting a dog in pose on a piece of furniture and trying to freeze that moment you're really documenting a performance,' says Selwyn. And in this way, the early work is not so different from the gorgeous dogs on gorgeous furniture; it just became more crafted, more lushly beautiful.

As originally featured in the October 2015 edition of Wallpaper* (W*199)

Fay/Ruscha, 1987. A memorable diptych of dog and artist

Big and Little, 1971. The image focuses on difference and duality

Ray Bat, 1980. An upside-down print turns a lying dog into a flying one

Paris in the Spring, 1971. An extra ’the’ throws a common phrase, pinned on old school chairs, off-kilter

Double Profile, 1980. Man Ray is paired with a human subject for the first time

’Checker’ fabric in magneta/orange, 1965, by Alexander Girard, from Maraham

’Library’ chair; ’Plank’ table, both by Robert Bristow and Pilar Proffitt, for Poesis Design, from Ralph Pucci. ’Mini Farrago O2’ light, by Jason Miller for Roll & Hill, from The Future Perfect

’Color Wheel’ ottoman in hallingdal orange, 1967, by Alexander Girard, from Herman Miller

’III Navy’ chairs, by Emeco

’Hairy J Blige’ double-hump bench, 2014, by The Haas Brothers, from R & Company

’Fiberglass’ chair, by Vladimir Kagan, from Ralph Pucci

Giant Cubebot, by David Weeks

’Burnt Stumps’ stools, by Kieran Kinsella, from BDDW

’Cube’ armchair, by Calvin Klein Home. ’Hexa’ rug in charcoal, by Ben Soleimani, for RH

’Deluxe’ chair, by Richard Shemtov, for Dune

’Ace’ counter stool; bar stool, both by Bernhardt Design

’Ring’ table, by Holly Hunt. ’XL’ vessels, by Eric Roinestad, for ER Studio, from The Future Perfect

’Darboux’ chair, 2013, by Craig Van Den Brulle

’Ab6’ bed, by Atlas Industries. ’Florence Stitch’ bed sheet; ’Oval Bands’ coverlet, both by Calvin Klein Home

’Turn’ stool, by Blu Dot, from ABC Carpet & Home. Pulley lamp, by Tyler Hays, for BDDW

’Windsor’ settee, by Christopher Specce, for Matter Made

’Crock I’ pot, by Tyler Hayes, for BDDW

Long Afternoon, by Wendell Castle, from Friedman Benda

’Penthouse Suite’ pedestal console, by Ralph Lauren Home

Fey Ray, 1979. One of Wegman’s first large-format Polaroid pictures

INFORMATION

Producer: Michael Reynolds

Wallpaper* Newsletter

Receive our daily digest of inspiration, escapism and design stories from around the world direct to your inbox.

-

Put these emerging artists on your radar

Put these emerging artists on your radarThis crop of six new talents is poised to shake up the art world. Get to know them now

By Tianna Williams

-

Dining at Pyrá feels like a Mediterranean kiss on both cheeks

Dining at Pyrá feels like a Mediterranean kiss on both cheeksDesigned by House of Dré, this Lonsdale Road addition dishes up an enticing fusion of Greek and Spanish cooking

By Sofia de la Cruz

-

Creased, crumpled: S/S 2025 menswear is about clothes that have ‘lived a life’

Creased, crumpled: S/S 2025 menswear is about clothes that have ‘lived a life’The S/S 2025 menswear collections see designers embrace the creased and the crumpled, conjuring a mood of laidback languor that ran through the season – captured here by photographer Steve Harnacke and stylist Nicola Neri for Wallpaper*

By Jack Moss

-

William Wegman gifts his entire short video catalogue to the Met

William Wegman gifts his entire short video catalogue to the MetBy Patricia Zohn

-

Witty and wonderful, William Wegman’s unseen Polaroids are instant classics

Witty and wonderful, William Wegman’s unseen Polaroids are instant classicsBy Charlotte Jansen

-

Canine design: William Wegman surveys his shots of new and used furniture in LA

Canine design: William Wegman surveys his shots of new and used furniture in LABy Aaron Peasley

-

Picture postcard: William Wegman’s painterly world at Sperone Westwater

Picture postcard: William Wegman’s painterly world at Sperone WestwaterBy Brook Mason

-

Canine connection: William Wegman’s Dogs in Coats is travelling to Max Mara boutiques across the US

Canine connection: William Wegman’s Dogs in Coats is travelling to Max Mara boutiques across the USBy Pei-Ru Keh

-

Colour me happy: RxArt’s fifth colouring book features cover art and stickers by John Baldessari

Colour me happy: RxArt’s fifth colouring book features cover art and stickers by John BaldessariBy Pei-Ru Keh

-

Game(s) on: Unit Editions reveals definitive Lance Wyman monograph

Game(s) on: Unit Editions reveals definitive Lance Wyman monographBy Jonathan Bell

-

Wild mystique: Ansel Adams retrospective opens at Quintenz Gallery, Aspen

Wild mystique: Ansel Adams retrospective opens at Quintenz Gallery, AspenBy Tom Howells