‘Worldbuilding’ exhibition review: a trip through the uncanny valley of art and gaming

Curated by Hans Ulrich Obrist, ‘Worldbuilding: Gaming and Art in the Digital Age’ at the Julia Stoschek Collection, Düsseldorf, explores how artists can embrace and subvert the visual language and culture of video games

YOU HAVE FAILED TO SUPPORT BLACK TRANS LIFE HERE

YOU MUST LEAVE

YOU DON’T DESERVE TO BE HERE

As a video game player since childhood, I had encountered unexpected moments, juxtaposition, and even anxious self-doubt. But still, it hit me when confronted with the rigid, capslock statement (above) in Danielle Brathwaite-Shirley’s SHE KEEPS ME DAMN ALIVE (2021), a first-person shooter game in which I was expected – and failed – to protect Black trans people from a variety of carefully crafted, yet digitally unrefined pixelated enemies. Within her cyber-HogarthinIan cityscape, I had tried to follow instructions to be an ally, but evidently failed.

Danielle Brathwaite-Shirley, SHE KEEPS ME DAMN ALIVE, 2021, Unity-Game installation, infinite duration, color, sound. Installation view, Arebyte Gallery. Courtesy of the artist. Commissioned by Arebyte, London (2021). On loan from the artist and ZELDA

Hans Ulrich Obrist, curator of ‘Worldbuilding’ at the Julia Stoschek Collection in Düsseldorf, says that the work ‘implicates the viewer’ in ways more traditional artworks may struggle to. Video games are less than 65 years old, the very first a basic spermatoid of the full-grown digi-splendour we experience now; it seems a very recent history while simultaneously rooted in our very modern cultural senses of identity.

Yet, like all new cultural angles – it took a century for photography to slowly become part of the artistic canon – it is seen outside of the artistic realm. Obrist’s new exhibition seeks to blend these two worlds, even though he has only been playing games for a few years, and then only as research for this exhibition.

Some of the artists showing, however, are much more deeply rooted in the art form – many having been born well into this century and not knowing a world not saturated by gaming and the aesthetic or cultural attachments to it. Brathwaite-Shirley is one, born in 1995. Their understanding of the physical world is barely detachable from their experience of the digital, and when articulated in such a present visual form as an interactive trans-defending game, it’s tangible.

Ian Cheng, BOB (Bag of Beliefs), 2018–2019, artificial lifeform, infinite duration, color, sound, dimensions variable. Installation view, ‘Worldbuilding’, JSC Düsseldorf.

We have been here before. In the mid-20th century, the art world was shaken by emergent social, political, and technical shifts. ‘This is Tomorrow’, a seminal, 1956 Whitechapel exhibition, foreshadowed pop art, featuring Richard Hamilton’s collage of a domestic home saturated with technology and capitalist ambition alongside a Frank Cordell electronic installation feeding back live ambient sounds of the audience. A later documentary of the exhibition by Reyner Banham suggested that ‘viewers are invited to enter strange houses, corridors, and mazes – this is modern art to entertain people, modern art as a game people will want to play’.

Walking around the gallery in Düsseldorf, that Banham quote has become true – this is a place about play. But here, play is considered, cultured, and meaningful. ‘If Richard Hamilton lived today, he'd certainly be interested in this phenomenon, there is no doubt whatsoever,’ Obrist tells me, explaining that the roots of the project come from conversations he had decades ago with Hamilton, theatre-maker Joan Littlewood and architect Cedric Price. Littlewood and Price developed the idea of the Fun Palace, an ever-futuristic model of a reflexive, playful, and communal architecture which, like so much of the 1960s, remained as a mirage lost in practicality. With new digital horizons, we may have found the fun palace of our generation.

Wallpaper* Newsletter

Receive our daily digest of inspiration, escapism and design stories from around the world direct to your inbox.

Jacolby Satterwhite, We Are In Hell When We Hurt Each Other, 2020, HD video and virtual reality installation, video still.

In 1968, the ICA exhibited ‘Cybernetic Serendipity’, which shook London, then the world on tour. Art informed or created by technology and robotics was terrifying, exciting, a gear-change in how culture was made. We are, it seems, at the same place now, living in a global uncanny valley – just as politically and culturally we are also shifting. These things align, and this exhibition seeks to be the button that instigates that moment of realisation.

Saturated with contemporary issues, and delivered in playful yet profoundly impactful ways, it’s perhaps no surprise that video games are a perfect mode to deliver artistic messaging and ideas. However, Obrist hadn’t played games until researching this project. This may be critically useful; some of us who have spent our lives between digital and physical realms, serious and play spaces, have a more rooted and less critical relationship. Obrist, however, has keenly carried out over 50 studio visits to ensure that he has included the most nuanced and progressive art angles upon gaming alongside the old guard, including Sturtevant, Rebecca Allen, and Larry Achiampong.

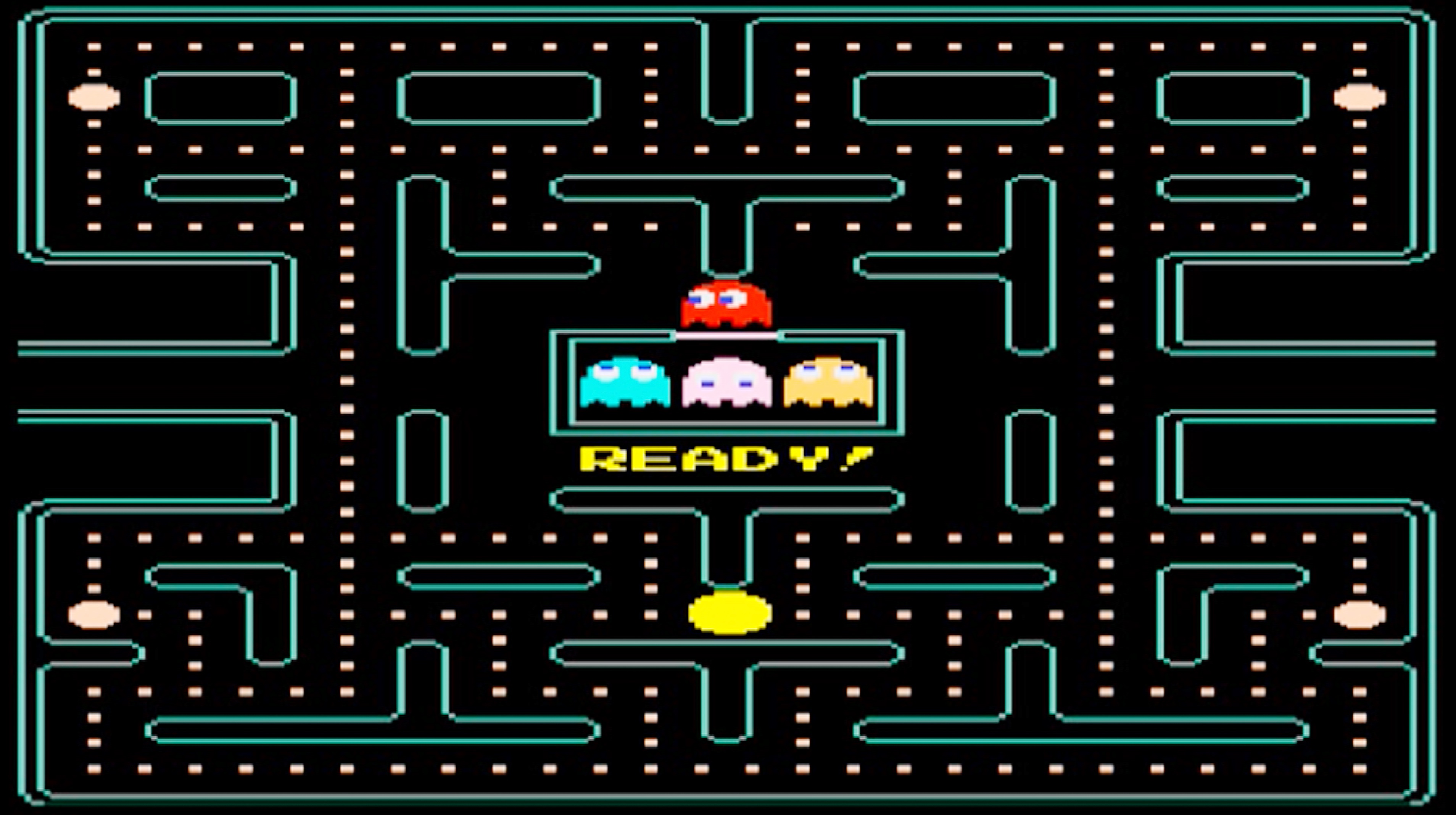

Sturtevant, Pacman, 2012, HD video, 1′15″, video still.

Not that these practitioners are old, so much as technology warps the sense of time. So, in terms of shifting digital aesthetics, what is only 30 years old seems antiquated. Some play with this; glitch and 8-bit aesthetics saturate the work, especially that of younger artists.

Some artists are archaeologists digging in the pits of decades-gone digital entertainment. The show opens with a Sturtevant work that reimagines Pac-Man as an artist-devouring auto-destructive demon, while Peggy Ahwesh grabs footage of an early Lara Croft struggling in a polygonal world, and uses it to create a deeply traumatic and emotional treatise on relentless death, rebirth, and struggle. I associated with it as both a bad Tomb Raider and as someone with existential angst.

Jodi, Untitled Game. Modifications of Video Game (Quake 1), 1998–2001, video game, untitled-game.org, infinite duration, color, sound. Video still.

In the next room artist duo Jodi leave a controller out to play a hacked Quake in one of their series, Untitled Game (1998-2001), here transforming the game’s rigid perspective into a moiré-hellscape where walls turn into greyscale Bridget Riley, but the traumatic audio of attack, shooting, and death remain. It’s a genuinely anxious experience, trying to escape but not knowing how.

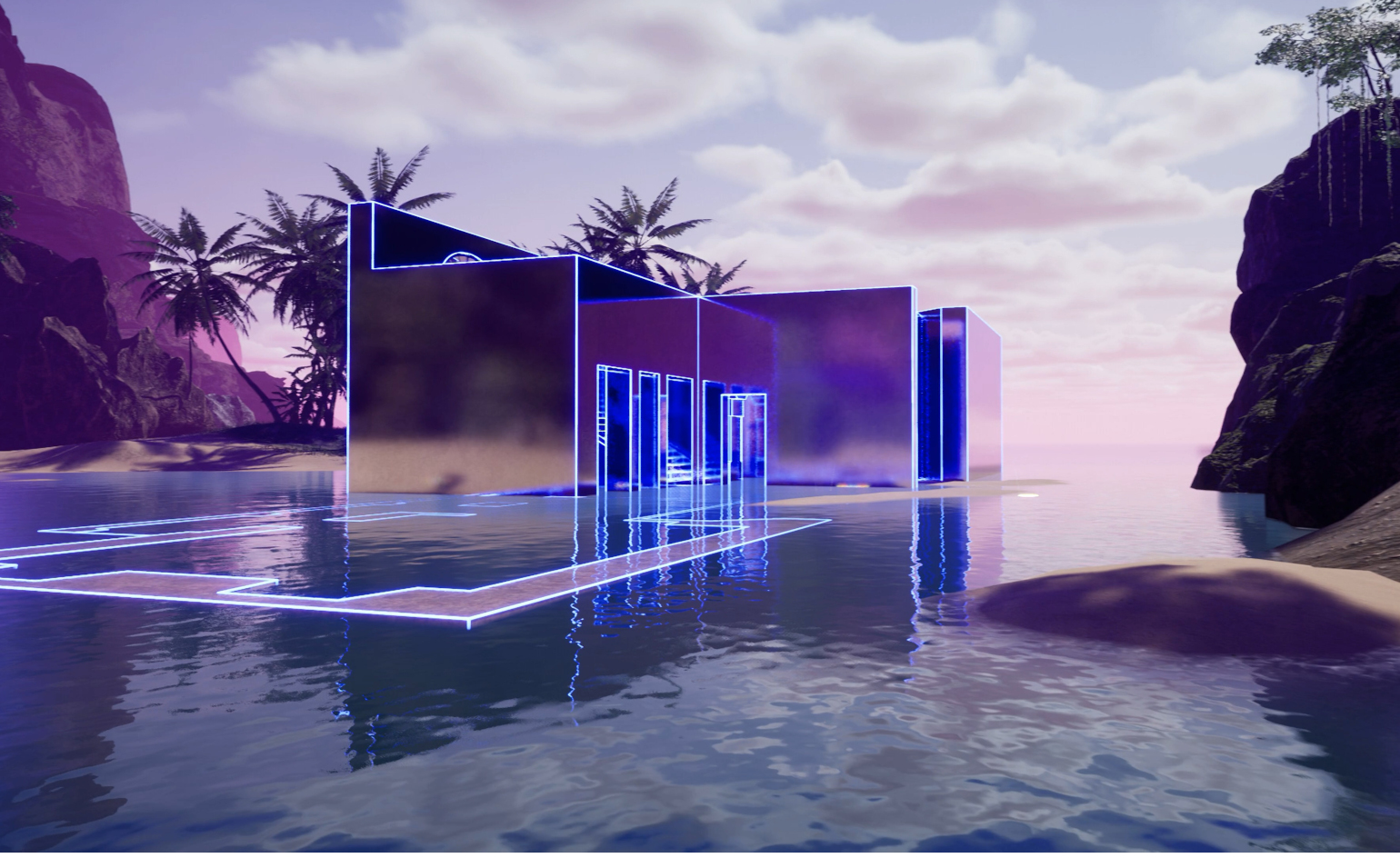

The exhibition physically packs into a very tight gallery space, but reaches beyond in two critical ways. Psychologically, it opens vistas: Caspar David Friedrich’s ideality permeates LaTurbo Avedon’s Permanent Sunset (2020-ongoing), capturing the artist-avatar relentlessly gazing at romantic gamespace sunsets, while The Institute for Queer Ecology’s island utopia H.O.R.I.Z.O.N. (2021) is a space where identity can be lost to an ideal of communality and world-building.

LaTurbo Avedon, Permanent Sunset, 2020, 6′13″, color, sound. Video still.

Physically, it also offers escape: various VR artworks trick the physical self out of the gallery space, while for Keiken’s The Life Game (2021), I – a 41-year-old cis man – lay back and had a relentlessly busy womblike appendage laid upon me, a soundscape marrying the action below to entirely take me out of my comfort zone and into a place of reconsideration.

In part due to the digital nature of the exhibition works, there is a world of creative experiences that far depart the physicality of the gallery space in Düsseldorf. However, this also offers a physical potentiality – Obrist tells Wallpaper* that ‘as the show continues here for 18 months, it starts elsewhere’, breaking away from analogue-conventional norms of works having to be packaged and moved and offering new possibilities to exhibition-making.

Theo Triantafyllidis, Pastoral, 2019. video game, infinite duration, color, sound. Installation view, ‘Worldbuilding’, JSC Düsseldorf.

By then, the show may look different. Having already carried out all those studio visits to ensure that new artists and ideas were present, Obrist will continue not only searching for new works to install in the show – during its lengthy run it will shift and change, as a modern AAA game is patched and updated – but will also commission and develop new works.

As politics saturates the physical, so it also saturates the digital. It is overtly present in works such as Brathwaite-Shirley’s (the guilt, privilege, and anxiety follow me) but ever present within more well-known projects like Harun Farocki’s Serious Games, documenting the tight industrial-game complex through young soldiers practising wargames via game simulators. There is a sense in this exhibition that we are at an age not dissimilar to the mid-20th century of pop art, cybernetics, and Tomorrowism. We couldn’t really imagine then just how the following decades' cultural and digital worlds would entangle so profoundly, and similarly, we perhaps can’t quite predict how games, AI, VR, and digital landscapes will inform the next generation of artists. This exhibition marks the start of that journey, and both the content and curatorial approach of ‘Worldbuilding’ over its 18 months may prove to be a seminal moment in how exhibitions meet the digital future.

Keiken, Bet(a) Bodies, 2021–2022, wearable haptic womb, digital audio, 9′12″, sound, silicone, LED light, minicomputer, haptics, amp.

INFORMATION

Will Jennings is a writer, educator and artist based in London and is a regular contributor to Wallpaper*. Will is interested in how arts and architectures intersect and is editor of online arts and architecture writing platform recessed.space and director of the charity Hypha Studios, as well as a member of the Association of International Art Critics.

-

Marylebone restaurant Nina turns up the volume on Italian dining

Marylebone restaurant Nina turns up the volume on Italian diningAt Nina, don’t expect a view of the Amalfi Coast. Do expect pasta, leopard print and industrial chic

By Sofia de la Cruz

-

Tour the wonderful homes of ‘Casa Mexicana’, an ode to residential architecture in Mexico

Tour the wonderful homes of ‘Casa Mexicana’, an ode to residential architecture in Mexico‘Casa Mexicana’ is a new book celebrating the country’s residential architecture, highlighting its influence across the world

By Ellie Stathaki

-

Jonathan Anderson is heading to Dior Men

Jonathan Anderson is heading to Dior MenAfter months of speculation, it has been confirmed this morning that Jonathan Anderson, who left Loewe earlier this year, is the successor to Kim Jones at Dior Men

By Jack Moss

-

Edinburgh Art Festival 2023: from bog dancing to binge drinking

Edinburgh Art Festival 2023: from bog dancing to binge drinkingWhat to see at Edinburgh Art Festival 2023, championing women and queer artists, whether exploring Scottish bogland on film or casting hedonism in ceramic

By Amah-Rose Abrams

-

Last chance to see: Devon Turnbull’s ‘HiFi Listening Room Dream No. 1’ at Lisson Gallery, London

Last chance to see: Devon Turnbull’s ‘HiFi Listening Room Dream No. 1’ at Lisson Gallery, LondonDevon Turnbull/OJAS’ handmade sound system matches minimalist aesthetics with a profound audiophonic experience – he tells us more

By Jorinde Croese

-

Hospital Rooms and Hauser & Wirth unite for a sensorial London exhibition and auction

Hospital Rooms and Hauser & Wirth unite for a sensorial London exhibition and auctionHospital Rooms and Hauser & Wirth are working together to raise money for arts and mental health charities

By Hannah Silver

-

‘These Americans’: Will Vogt documents the USA’s rich at play

‘These Americans’: Will Vogt documents the USA’s rich at playWill Vogt’s photo book ‘These Americans’ is a deep dive into a world of privilege and excess, spanning 1969 to 1996

By Sophie Gladstone

-

Brian Eno extends his ambient realms with these environment-altering sculptures

Brian Eno extends his ambient realms with these environment-altering sculpturesBrian Eno exhibits his new light box sculptures in London, alongside a unique speaker and iconic works by the late American light artist Dan Flavin

By Jonathan Bell

-

![The Bagri Foundation Commission: Asim Waqif, वेणु [Venu], 2023. Courtesy of the artist. Photo © Jo Underhill. exterior](https://cdn.mos.cms.futurecdn.net/QgFpUHisSVxoTW6BbkC6nS.jpg) Asim Waqif creates dense bamboo display at the Hayward in London

Asim Waqif creates dense bamboo display at the Hayward in LondonThe Bagri Foundation Commission, Asim Waqif’s वेणु [Venu], opens at the Hayward Gallery in London

By Cleo Roberts-Komireddi

-

Forrest Myers is off the wall at Catskill Art Space this summer

Forrest Myers is off the wall at Catskill Art Space this summerForrest ‘Frosty’ Myers makes his mark at Catskill Art Space, NY, celebrating 50 years of his monumental Manhattan installation, The Wall

By Pei-Ru Keh

-

Jim McDowell, aka ‘the Black Potter’, on the fire behind his face jugs

Jim McDowell, aka ‘the Black Potter’, on the fire behind his face jugsA former coal miner, Jim McDowell defied the odds to set up his workshop and keep a historic form of American pottery alive

By Aruna D’Souza